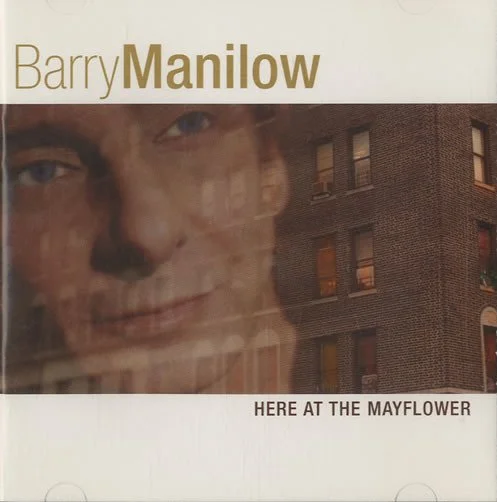

Barry Manilow “Here at the Mayflower”

The cleanup hitter for the 1979 River Vale, New Jersey police department softball team was a guy named Aaron. My dad, who was not a cop, played for a team called “R-Gang” who lost to the police department team twenty-six to two. It was a complete humiliation, full of hard line drives and smooth fielding by the officers and feeble ground outs and bobbled balls by my father’s lawyer and doctor friends. Aaron was the MVP that day, hitting several mammoth bombs over the head of a textile salesman in right field and a dentist and father of two in left.

When I was five, I was only aware of two men named Aaron — Cop Aaron and Henry Aaron, major league baseball’s all time home run king. Cop Aaron was a sturdy Jersey guy. Average height, but above average muscles. Mustache. Big chest and forearms. He looked nothing like Henry Aaron. For one thing, Cop Aaron was white. And, while I’d not yet turned five, I was smart enough to reason that Henry Aaron had probably not joined the River Vale police department. Logically I knew that the two Aarons were not the same guy. But also, I was not 100% sure. Maybe there was only one home run hitting Aaron. Maybe they were the same guy. I mean, how could there be two of them?

The adorable confusion of youth — when Cop Aaron might also be Henry Aaron, when you still think that cartoons might also be your real life friends. When your dad, whose name is Barry, tells you that he sang in a Fifties vocal group named Barry and the Tamberlanes and you are pretty sure he’s pulling your leg but you can’t prove it. And when you are confused as to whether Barry and the Tamberlanes has something to do with Barry Manilow, who you’d seen on TV and heard on the radio and who looked and sounded like all your parents’ friends from Brooklyn and Queens, including quite a few men named Barry. It was 1979. Yes, in retrospect, it was adorable. And, yes, at the time, it was confusing.

It wasn’t just the Aaron or Barry of it all. It was the beige wash of the Seventies. Everything was hazy. Everything was tan. Everything kind of looked alike and sounded sad. If you were there, you can maybe understand why I was confused by Barry Manilow. For instance, I could not fathom how he was not the lead singer of Air Supply. To me, they sounded exactly the same How was “Mandy” different from “All Out of Love”? Or — OK — if he wasn’t in Air Supply, he must have been one of the guys from Sigfried and Roy. Right? Or maybe he was both of them? How else could you explain the resemblance? Also, was he related to Barbra Streisand and Neil Diamond? Was he their cousin? Was he my cousin? If not, why did my parents have so many albums him? And from Barbra and Neil for that matter. Plus, Barry said that he “writes the songs” and that he “is music.” Was he being literal? My young brain certainly considered the possibility.

It took me another five years to sort everything out. That Barry Manilow was not, in fact, a member of Air Supply. That he was not related to Barbra Streisand or Neil Diamond or — best as I could tell — my father, Barry. By that time, it was 1984 and Manilow’s extraordinary run as the feel good, sad sack, New Yawk, cabaret act turned Pop star had run its course. Post-Disco, post-Punk, during the peak of New Wave and Michael-mania, Barry Manilow was beyond passé. He was less cool than uncool. He’d been lapped by Air Supply and REO Speedwagon, acts who owed their mammoth success to him.

Where Air Supply and REO rocked just enough, however, Manilow rocked not at all. Where they played it straight, Manilow embraced the camp. Yes — the rejection of Manilow had more than a twinge of homophobia. But mostly it was a rejection of the previous decade. He was not alone — so many of those iconically Seventies stars had disappeared. ABBA. The Carpenters. Captain & Tennille. But they literally went away. ABBA retired. Captain & Tennille put the act on the shelf. Karen Carpenter died. Manilow, on the other hand, simply receded from Pop royalty to beloved, but more so uncool cult artist. His audience went from being anyone over the age of thirty with a record player to fans of Bette Midler, Liza Minelli, Jewish grandmothers from New York, and — maybe most of all — Oprah Winfrey.

Over the course of his career Barry Manilow has sold more than eighty five million albums. That’s more than Tom Petty, Nirvana or KISS. He has nine platinum selling albums. He has twenty-five top forty Pop hits and nearly fifty top forty Adult Contemporary hits. Beginning in 1974, with “Mandy,” he was the yellowing wallpaper of America. His music was all over the radio, in grocery stores, waiting rooms and elevators. Just a decade later, however, he’d hit a wall. “2:00 AM Paradise Cafe,” released that year, underperformed. It produced no hits and barely struck Gold. It was also his last album of originals for two decades. Yes — the man who wrote the songs (but who I later learned did not write “I Write the Songs”) stopped writing the songs.

But he never stopped working. He made Christmas albums. He made Jazz albums. He played Sinatra. He sang his favorite songs of the Fifties. And the Sixties. And the Seventies. And the Eighties. And then he made another Christmas album. He wrote his autobiography. He popped up on Oprah. And, in 1999, he performed on StarSkates Salute to Barry Manilow at the Mandalay Bay Hotel, which I can confirm is exactly what it sounds like. That’s where Barry Manilow was at the end of the last century.

Though his star had faded, it never went out. And he never resisted the changing of the guard. He never held on too tight. Manilow knew that he’d never be hip again. He knew that he probably was never hip to begin with. But by the time of Prince and Madonna, Barry had everything he could ever need. He had a loving partner. He had walls full of platinum records. He had causes to support. He had security, freedom and independence. But the question that hung in the air for his fans — the thing that they most wanted to know — was whether he still had the songs? And, if so, where was he hiding them?

It took twenty years for the answer to reveal itself, but, in 2004, Manilow returned with “Here at the Mayflower,” a sixteen song concept album about the Brooklyn apartment building that he lived in as a child. In many ways, his nineteenth studio album was his most ambitious, hopping from cabaret to showtunes to swing to mambo to torch songs to pop music over the course of an hour. As importantly, Manilow wrote or co-wrote every song on the album. More than any of his Seventies albums. More than the (many) albums named “Barry Manilow,” “Barry,” or “Manilow,” “Here at the Mayflower” is the definitive Barry Manilow album. It’s the soundtrack to a New York story that should have been staged on Broadway. One that Manilow might have intended to be staged on Broadway. But, one which was never staged at all. It’s a theatrical show disguised as a concept album. An autobiography disguised as the diorama dramas of others. A grand, late career surprise that barely dented the charts and would have quickly faded into obscurity had it not been for Terry Gross and Oprah Winfrey.

While the thinner herd of Manilow loyalists had waited twenty years for new, original material, “Here at the Mayflower” was actually sixty years in the making. It’s not merely autobiographical — though it is absolutely that. It’s also a formal summation of his career, tackling the styles that most mattered to him and exploring those themes — longing, romance, hope — that endeared him to millions and turned off almost as many. “Here at the Mayflower” combines the voyeurism of “Rear Window” with the insularity of “Only Murders in the Building” and the New Yorkness of “In the Heights.” It’s as enterprising as it it schmaltzy.

Those nostalgically hoping for another “Mandy,” however, will be disappointed. This is not a Pop or Lite Rock record. This was not an album conceived to win new fans. In truth, it’s not an album that I would have ever sought out, nor is it one that I will ever listen to again. I’m fifty years old and I have my things and this is not one of them. But, “Mayflower” is wildly impressive nonetheless. It contains musical breadth and emotional depth. It achieves the thing that Barry Manilow always had a knack for — it makes you feel something. Even when his songs played in elevators, even when the material was willfully sad, even when he was trying to goose up old Christmas songs, he had a knack for arranging in a way where hope eventually shines through. It can be off putting — annoying even. But it is undeniable. You don’t sell eighty-five million albums by depressing people.

“Here at the Mayflower” takes us apartment by apartment. The title of each song is preceded by the apartment number — 3B, 5H, 6C, etc. — before setting the scene and introducing us to the characters within. In 3B Diane wants to get out of Brooklyn. In 5N, Ken wants to lose weight. In 6C, Esther and Joe, the building’s oldest couple were once not so old — she had a pair of legs and he had a head of hair. There are dreamers dreaming and lonely hearts longing. Some couples are aging, while others — the typist and the mechanic — shed their work clothes at night so they can go out and dance like John Travolta and Janet Jackson (his names, not mine). While its themes are universal, it’s also an album that could have only been made by someone who came of age in Brooklyn during the Fifties, who was a keen observer of life and who could write songs in every popular music style from the twentieth century. That’s a pretty short list. In fact, it may be a list of one.

Roughly half of “Mayflower” consists of plaintive, slightly jazz ballads — torch songs and reveries about the other side of the river, or the isolation of gazing out at the big city, or lifetimes full of could ofs, should ofs, would ofs. But Manilow’s sense of melody radiates through all of the yearning and reverie. His voice, on the other hand, is an acquired taste that I simply never acquired. There are many reasons why he started off his career as a writer, arranger and accompanist — but the most obvious one is that his voice is more plain and accurate than it is pretty or interesting. Along with Debbie Harry, Joey Ramone and Billy Joel, Manilow has one of Rock’s truly unadorned New York accents. It can be familiar and comforting, but it also pulls me out from his songs, back to the adult softball games of my youth, where my Dad, named Barry, and his neighborhood friends, also named Barry, sounded a lot like Barry Manilow.

In between the softer fare, Manilow offers up a selection of vaguely jazzy, slightly funky stuff that would be perfect for the hors d'oeuvres hour at a Bar Mitzvah — “Come Monday” being the best of that breed. There’s surprisingly good Mambo number called “The Night Tito Played” and there’s a not quite good enough AM Gold nugget called “Turn the Radio Up,” that evokes Van Morrison’s “Caravan,” but, in doing so, also reminds us of that thing that Van has which Barry does not: Soul.

But it’s the genre stuff that really stands out. “Freddie Said” is a bracing two minutes of Swing about the guy from the neighborhood who talked too much and, as a result, got offed. It’s the sort of song that Brian Setzer should have written and that David Johansen could have a ball with. In Manilow’s hands, it’s less exciting and interesting than either of those scenarios, but it’s a hoot nonetheless. “They Dance!” is the obligatory Disco track, perfect for a late Seventies skating rink but updated enough to make you realize that Pharrell was maybe not all that original. It’s got an above average, sub-Moroder beat and could easily have been the theme song to “Saturday Night Fever,” had that film not been a tragedy. It’s better than what you might expect and almost exactly what you’d hope for from a Barry Manilow Disco song.

Seven years before “Here at the Mayflower” was released, Manilow and his songwriting partner, Bruce Sussman, staged previews for “Harmony,” a show they’d written about a group of German Comedian Harmonists before World War Two. Cursed from the outset, “Harmony” stumbled its way through reviews, first in San Diego, then barely in Philly, before the it was shuttered due to insufficient funding. The show resurfaced years later, first in Atlanta and then in Los Angeles, before quickly closing again. Miraculously, it made its way to off Broadway in 2022 and, finally, to Broadway in 2023. I’ve never seen the show, nor have I heard the cast album, which was released in August of this year. So, while I can’t attest to the greatness or awfulness of “Harmony,” I can say with high certainty that it was not the musical that he was destined to write. “Here at the Mayflower” is that musical. It is the apotheosis of Manilow. And, if “Harmony” is any indication, “Mayflower” should be on stage in West Palm Beach, Florida, by the year 2031. By that time, Barry Manilow will be eighty-seven, largely forgotten, grossly misunderstood and terribly underappreciated, but still beloved by the sliver of Americans who still have VHS tapes, and whose collection includes “Yentl,” “The Color Purple” and “The Jazz Singer.”