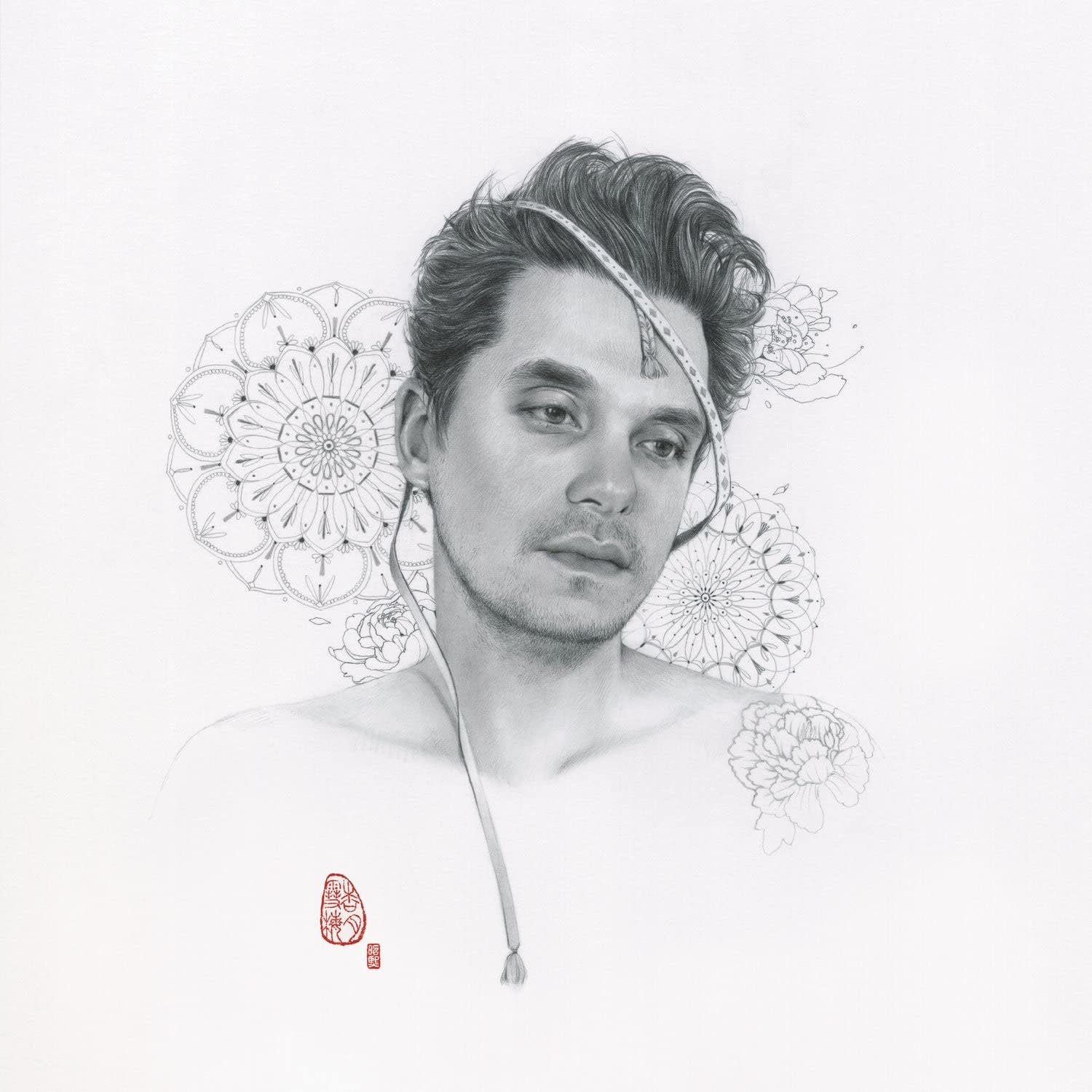

John Mayer “The Search for Everything”

Taylor Swift has her “Eras,” Dylan has his phases, and Bowie had his changes. In the case of Taylor, the iterations felt gradual, in part because she started out so young but also because, in the age of social media, we got to see them up close. In the case of Dylan, they seemed more opaque, less predictable. But, we always assumed that they were rife with intention and that time would reveal their true meaning. In the case of Bowie, they were radical, but also completely measured. Through a series of sharp turns, gradual bends and forks in the road, each of these great artists ended up somewhere far away from where they began. But that’s to be expected. For the great ones, change is the constant — it’s both normal and necessary.

The inverse, of course, would be a major problem. AC/DC notwithstanding, arrested development correlates to commercial stagnation and, eventually, regression. If the artist doesn’t move on, the zeitgeist will. And, moreover, the wells only runs so deep — if the artist is unable to find new inspiration in new places, they risk diminished returns, and degraded copies of their previous, more inspired originals.

However, in between evolution and regression (or, in reality, outside those two poles) is a curious third case. It is less a journey and much more like a snowball. The artist rapidly changes through increasingly shorter intervals. Their next evolution includes everything from their previous ones but with new, more intense features and affects. It’s not Ziggy Stardust to Thin White Duke. It’s Ziggy plus The Duke plus everything else that came before. The rate of change is neither gradual nor unpredictable — it’s faster and faster and faster still. With every turn, a new shell emerges on top of the old shell — like a Russian nesting doll, speeding downhill. Faster and faster. More and more.

To my knowledge, this phenomenon was first observed by my friend Kevin, who occasionally writes here for Past Prime and who is absolutely not a doctor, but who is a very keen observer of human behavior. He called it “APS” — Accelerated Personality Syndrome. For those exhibiting APS, the need for stimulation and the capacity to respond to said stimulation increases exponentially over time. If you see someone with APS, and then you see them again six months later, they will present their former self, but also many new selves. A close friend would discern the layers, but to a less familiar observer, the subject with APS might appear unrecognizable from their slightly younger self. It’s not so much that they have grown, as they have expanded and hastened. And while those with APS absolutely risk burnout, they tend to be brilliant while ablaze. They are luminescent rainbows and kaleidoscopic Jackson Pollock paintings all at once, to the power of infinity.

If Taylor is the exceptional normy, her ex, John Mayer, is the exceptional exception. Mayer is the public face of APS, having morphed from dewy, precocious, Adult Contemporary troubadour to unexpected ladies man to stand-up comic to paparazzi darling to loathsome heel to Montana recluse to older and wiser bluesman to self-aware Deadhead to legendary watch collector to Instagram fashionista in the span of two decades. Except that he never went “from” “to” anything — he went “from” “and.” As a result, middle-aged Mayer, with his six-figure watches and tie-dyed hoodies and luxuriant hair is still that young, doe-eyed Adult Contemporary hero and still that bachelor cad and still that part time comic. Those with APS never shed their former skins, they simply put on more outfits and accessories, faster and faster. It’s what makes them so interesting — there’s something for everyone. But it’s also what makes them hard to handle — they can be a bit much. And if they are not careful, too much.

But here’s the thing — John Mayer knows this. He knows all of this. Presumably, not the APS stuff, because the World Health Organization has yet to formally recognize our work. But all of the other stuff? His traits, his tics, his tells? He definitely knows them. In fact, I’d suggest that John Mayer is the most self-aware musician on the planet. Maybe the most self-aware musician of all time. He understands why he is popular and desirable, but not cool. He understands how and why his interest in fashion (and make-up) plays on social media but less so with critics. He knows exactly why the dumb stuff he said is dumb and why he is still single and why his music is so broadly appealing, but also so frequently derided. He knows what funny is but why he is not always so funny. He knows that to be a ladies man is also sometimes to be the villain. His self-knowledge — the fact that he gets it — is disarming. It is impressive for sure, and attractive to many. But, at the same time, it is totally, completely unbearable to others. And, when I say “unbearable,” I don’t mean odious or loathsome. I mean quite literally unbearable — impossible to handle.

That’s the line that Mayer walks — between “amazing” and “insufferable.” He is a preternaturally gifted musician who plays guitar with the cool fluidity of his heroes, Robert Cray and Eric Clapton. As a composer, his mastery extends far beyond his ostensible peers — Maroon 5, Jack Johnson and Jason Mraz. Since his arrival, even when he hadn’t figured out his hair game or what to do with all those Gap sweaters, Mayer has been tall, dark and handsome. He’s a prerenially great interview — frequently too great. It’s the speed and intensity of his amazingness, however, that unnerves. Going from Jennifer Love Hewitt to Jessica Simpson to Minka Kelly to Jennifer Anniston to Taylor Swift to Katy Perry in close succession. Hanging with Dave Chapelle one night and jamming with Bob Weir the next night. Or, the same night. Swapping Nikes for Uggs, splitting the difference between Burning Man and the runways of Paris. Wearing shades that are more expensive than his already expensive shoes, and watches that are tenfold the cost of either. It’s all amazing. And it’s all insufferable. And he knows it. And that knowingness can disarm some but never all of it. Because as bright and quick witted as he might be, he can’t catch the next version of John Mayer.

For every person who objects to Mayer’s public image, however, there are many more who take issue with his music. Critics complain that it is boring, indiscernible from his peers and his acolytes (Ed Sheeran, Shawn Mendes). Others bristle at its blandness, likening it to background music. And though I understand both appraisals, neither really holds water. To start, Mayer’s music is more varied and adventurous than “Your Body is a Wonderland” would have you believe. His oeuvre reaches far beyond the jangly, tepid Soul of his closest comparables. If nothing else, Mayer is a consummate musician, and an elite songwriter.

Moreover, background music is not necessarily boring or worthless. Al Green sometimes recedes after his aphrodisiac benefits set in. Brian Eno made music for airports. The American Analog Set’s drone can be so sweet it eventually disappears. Gia Margaret’s piano pieces have a mystical quality that verges on ethereal which verges on tenuous. And while I think it is fair to call Mayer’s music “ubiquitous,” that is primarily a matter of it being friendly to assorted radio formats and contexts. But, to the extent that it is background music, Mayer plays closer to the foreground than many of my favorite artists and albums.

So what, really, is the problem with Mayer? If I had to venture a guess, I’d say it was a self-awareness so profound that it borders on self-obsession. For some people (myself included) Mayer is simply too much — his seeming need to be everything, everywhere, all at once can be off-putting. He desperately wants to be liked, and more so wants to be loved, but also really, fully wants to be clear that he is OK with those who neither like nor love him. And that “love me, love me, no it’s cool, I get it” can present as glibness. Similarly, the greatness of his craft betrays the innocuousness of his style, which makes for a complicated effect. It can all feel like a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Or rather, a wolf in Visvim, Nike, Supreme, Louis Vuitton and Rolex. It can feel like he is seducing you with some ulterior motive. Like he’s loving you specifically to leave you. Or rather that he’s loving you to be loved and then to leave you.

That’s the thing that most separates him from Dave Matthews and Mumford and Sons — John Mayer’s ulterior motive seems more ulterior and more motivated. Which makes his eclecticism appear pretentious and his innocuousness appear dangerous. And I suppose it was for that reason, more than any other, that I actively avoided him for so many years. In spite of recognizing his talent and admiring his style and noticing his wit and acknowledging his intelligence, I felt compelled to steer clear. I simply did not trust the man.

By 2017, however, my fear had thawed. Mayer was forty — a bougie mountain man from Montana. He was quieter — a subdued lead guitarist, but also a side man in Dead & Co. He was broken up from Katy Perry and purportedly heartbroken. He’d fucked up — royally and repeatedly. But he’d apologized and eaten some crow. Plus, compared to Ed Sheeran and Shawn Mendes, he didn’t seem so bad. Or rather, he seemed more complicated, but also better.

In January of that year, Mayer released a four song EP entitled, “The Search for Everything: Wave One.” And while I rolled my eyes at that title, I was open to the sentiment. After all, I was just a few years Mayer’s senior and not unfamiliar with existential yearning. And yet, still wary of his APS, I did not press play. Same with the follow-up EP, “The Search for Everything: Wave Two,” which arrived in February. But then came the full album, which shared the same name and songs as those two EPs, except with four new ones added for good measure. I’m really not sure what changed for me in the two months between the second EP and the official album. It was not the radio — I’d not heard a single track from the album. I don’t think it was social media — I don’t follow the guy on any platform. So, it must have been that New York Times headline: “John Mayer Knows He Messed Up.” The promise of redemption. The promise of sobriety. The promise of a genuine R&B album with genuine blues. The promise that, after all that waiting, the world really had changed.

So, I pressed play on “The Search for Everything.” And though I did not get most of what I felt I was promised, I got so much more. Mayer’s seventh studio album is more stylistically adventurous than its predecessors, but it is similarly, immaculately performed and recorded. What he gives up in strum, jangle and soul, he makes up for with bass, feel and blues. His voice is not what it once was — those vocal cords never fully recovered from the chronic inflammation that sidelined him for much of 2012. But he offsets the loss with more falsetto, perfect pitch and frequent harmonies. “The Search for Everything” is not the D’Angelo-ish record that some press suggested, but it could easily pass for early Hall and Oates, which is not such a bad thing.

As for its grandiose name, “The Search for Everything” is only existential in the way that a breakup can feel existential — like a death. And while the record does also toil in the “moving on” phase of the breakup, it mostly lives in the wallow of finality. To its credit, though, that is also where it thrives. “Still Feel Like Your Man” is the record’s opener and its standout, emulating Darryl Hall by way of Teddy Pendergrass. Famously mopey, it includes a line about John keeping a bottle of shampoo for her at his place in case she ever wants to wash her hair again, a patently ridiculous idea that he acknowledges in the very next line when he confirms the obvious — that she definitely has her own shampoo and will not actually need to return to his place to wash her hair. I mean, it’s Katy Perry we’re talking about. Nonetheless, and in spite of the cringe, “Still Feel Like Your Man” succeeds as a sad sack, R&B anthem, the sort of thing that anyone who’s ever been dumped, or who’s ever ended things and regretted it can relate to.

But wait, there’s more — so much more. “Emoji of a Wave” might be the most 2017, post-Katy John Mayer title possible, but it’s also a lovely distillation of an idea and a feeling. Just acoustic guitar, some strings and John singing to himself, texting his ex to let her know that he’s thinking about her and that he’s hurting, but also that he knows it will pass (hence the wave emoji). And when he’s not pining, he’s wondering if he’ll ever not fuck things up. “In the Blood’s” Mumford-ness(handclaps, folksy and uplifting) succeeds because its hopefulness plays against the darkness of a much deeper question: does Mayer keep breaking up and breaking down because he’s from a broken home?

Even more than Al Green or Teddy Pendergrass or Eric Clapton or Robert Cray, middle-aged Mayer sounds a lot like Boz Scaggs. And specifically like Boz Scaggs in his 1970s prime when most of Toto was his backing back — cool, bluesy, jazzy and weird. “Moving On and Getting Over” and “Rosie” are both pure Boz — immaculate rhythm and blues with sharp lead guitars and deft rhythms, wrapped up in a silky smooth package and lite enough to play in the background.

Mayer closes with “You’re Gonna Live Forever in Me,” a spotless, McCartney-esque gospel that is the inverse of the album’s opener. Whereas “Still Feel Like Your Man” still begs for validation, the final track offers his ex the solace that, while he has moved on, she still resides somewhere in his heart. In fact, she will always reside in his heart — somewhere next to Taylor, Jen, Minka, the other Jen, Jessica and Courtney. It’s a beautiful song, as wistful as it is narcissistic.

“The Search for Everything” is a very good album that (unsurprisingly) critics either dismissed or despised. Nevertheless, it sold tons of copies, at a time when almost nothing did. Similarly, Mayer headlined arenas in support of the album, at a time when no other American singer-songwriter did. Mayer is the exception — the Pop star who rarely has a Pop hit. Case in point, this album produced zero Top Forty hits and only one Adult Contemporary Hit (“Love on the Weekend”). And yet, somehow, in spite of the fact that it is absolutely not a “Rock” record, every single song on the album reached the top forty of the Rock radio charts. Twelve songs, twelve top forty Rock radio hits.

As unlikely as that might seem, it’s downright logical compared to the central argument of the record: that John Mayer is a gutted, a puddle of feelings — sad, lost and lonely without his ex. In this telling, we are asked to assume Mayer is the “dumpee,” which is fine except for that facts that (a) he is the king of “it’s not you, it’s me” and (b) most every other account indicates that the break-up was either mutual or initiated by “Mr. Slow Hand, Jr.” And that is what I most bump up against with Mayer. It’s not the liteness of his music — I can get down with easy listening. It’s not the too revealing, can I smell your hair lyrics. I don’t mind that he dates famous, beautiful women or that he dresses like a character from “Zoolander” or that he has great hair (he really does) or that he became a Deadhead in 2015 and basically joined the band that same year. It’s the unreliable narrator problem — the fact that I just don’t believe him and I sense that he desperately wants us to believe him.

No matter how well he sells it, it’s hard to buy the bit from a guy who keeps moving on from the last bit. The guy who made “The Search for Everything” was already gone by the time it came out. Katy was ancient history and John was some other dude in newer Nikes, ruminating on Instagram Live about limited edition Japanese t-shirts and Dead & Co. Not long after the radical earnestness of this record, Mayer returned with “Sob Rock,” a more direct homage to Boz Scaggs, but also a complete undercutting of its title and its predecessor. Obviously, that’s the point — which perhaps makes John Mayer clever or funny, but also why I don’t trust him. He is allowed to be the guy from “The Notebook” and he is allowed to be Lloyd Dobler from “Say Anything.” But he can’t be those guys and be Tyler Durden from “Fight Club.” The problem with APS is the problem with unreliable narrators: they try to have it all ways.