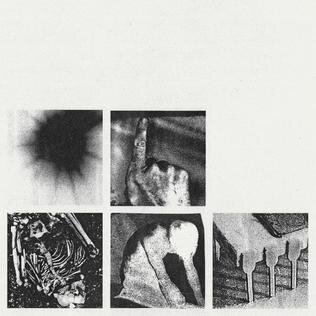

Nine Inch Nails “Bad Witch”

I first heard Nine Inch Nails in early 1990, on Long Island’s once great, famously alternative radio station, WDRE. At the time I was a pretentious teenager, deep in the Rock cannon, exploring Elvis Costello, The Clash, The Rolling Stones and the like. I was curious about Goth music and understood its appeal, but I managed to avoid any real seduction. Additionally, I didn’t really know much about Electronic music, aside from experimental or ambient music, like Brian Eno’s, or danceable Pop music, like Disco. Hardcore was popular around New York at the time, but I was far too beta to partake. So, when I first heard “Head Like a Hole” back then, it sounded to me like Skinny Puppy covering the Pixies. There was a din that I vaguely associated with an admittedly scant knowledge of Industrial music. But there was also a quiet/loud/quiet structure and sense for melody that sounded like what was then called “College Rock.” When that song came on the radio, I perked up. I definitely appreciated it, but I did not consider the matter beyond that.

The next year, in the summer of 1991, I attended a summer arts program at a college in Vermont. It was completely precious, pastoral, coming of age stuff — an idyllic locale wherein I could learn about writing and, moreover, about girls. That summer was pierced, however, by a series of bizarre, vaguely sadistic notes that I received from an anonymous source that accused me of being a vampire. You see, I have two birthmarks on my neck that, from a distance, could double for bite marks. Beyond that, however, I share none of the darkly good looks or charisma of the bloodsuckers. In these notes, which sometimes were accompanied by gruesome drawings or decapitated baby doll heads, I eventually recognized lyrics from “Head Like a Hole.” Upon further investigation, I learned that many of the words were culled from NIN lyrics. Before the month long program came to its end, the culprits revealed themselves. Unsurprisingly, it was two very nice, arty teenage girls and their completely sensitive, Gothic boy partner. What was unnerving to me for weeks felt relieving, but also kind of sad. I left the summer and returned home with the sense that Nine Inch Nails was music for my tormentors. I decided it was simply not for me.

For most of the 1990s and early 2000s, I was able to sustain my avoidance. I had my music. I had my heroes. And they did not have stringy long hair, sport a triangular soul patch or wear a black trench coat. They did not peddle sadomasochism to teens. They did not headline Lollapalooza. They did not inspire Harry Potter’s Professor Severus Snape. They were not chummy with Marilyn Manson. No. My heroes were singular geniuses and talents making transcendent Rock music for discerning adults. I was a young adult and serious music fan, after all. No Nine Inch Nails for me, thank you very much.

And yet, I increasingly had to acknowledge that there was something about the music. And the guy. NIN occupied this previously unthinkable space between Industrial, Goth, Experimental, Dance, Hardcore and Pop. In its exceptionalism, it tapped into incredibly diverse audiences. And while I was more an evader than a completist, every song I heard from the band was remarkable in its obsessiveness and its texture. I was not evolved enough to put aside my biases, but I was smart enough to realize that Trent Reznor had a profound vision for his art that went well beyond trend or cliche.

Eventually, with distance from “Hurt,” which was impossible to ignore, and from “Pretty Hate Machine,” which had nearly scarred teenage me, I was able to revisit Nine Inch Nails. The second approach was not swift. However, by 2008, Trent Reznor had cut his hair to a photo-ready bob, had bulked up like 80s Lou Reed and had reportedly gotten sober. What I heard from “With Teeth” and “Year Zero” sounded similarly coiffed to my ears -- a notch cleaner and with more expensive beats. I secretly missed some of the noisy, visceral, carnal rush of the early songs, but I was beginning to appreciate what seemed like clearheadedness. That being said, I sensed that it was too late for me to join the party. I was in my mid-30s. Plus, the club felt too intense and religious to me. In my mind, the music required secret codes and easter egg downloads and video game hacks and unsolvable puzzles. In the mid-2000s, I believed that listening to NIN necessarily required immersing myself in a multi-media experience that was actually a test for something that I probably would not understand.

As the first decade of the new millennium concluded, Reznor’s universe expanded even further. He married singer and future collaborator Mariqueen Maandig and cemented his relationship with producer, Atticus Ross. Increasingly, his music was leaning towards the expansive and experimental side of his tastes. His love of Brian Eno and David Bowie was coming to the surface. And, although I was loathe to admit it, Trent Reznor was thinking about music, technology, psychology and geopolitics with an exacting vision and fluency that was equal to, if not greater than, that of Radiohead of Bjork or other artists I unabashedly admired.

In 2010, having been completely floored by Reznor and Ross’ score for “The Social Network,” I knew that the moment had come. The time for avoidance was up. It was not his fault that a bunch of teenagers with Bauhaus shirts and black lipstick had spooked me. It was not his fault that Alt Rock culture had collided with mall culture. I could no longer dismiss Nine Inch Nails’ music. What had started as willful dismissiveness was beginning to feel like ignorance. Trent Reznor had fully cut his hair and was wearing what seemed like functional, comfortable athleisure. He had children. He had grown up. He was, by this point, fully a middle aged man. And I was not far behind. If he could bury the S&M whips and chains couldn’t I bury the hatchet?

Beginning in 2010, I waded into new Nine Inch Nails’ music gradually, but whole heartedly. The film scores were a complete pleasure -- dark, beautiful, spare and affecting. 2013s “Hesitation Marks,” while not revelatory, was accessible for me. The beats were more muscular and the programming more intricate. In some ways, the music resembled what critical darlings LCD Soundsystem were making at the time. On “Hesitation Marks,” the highs were not as high as his iconic hits. But the fury was less cartoonish to me. There was deep introspection rather than reductive self-loathing. The entire affair sounded more existential than adolescent. Further, with Ross’ considerable help, NIN had developed a breathtaking ability to build up textures to their breaking points, only to then remove everything that was inessential. Middle-aged Trent Reznor did not sound as furious as the guy I had avoided, but he sounded doubly focused.

In 2015, Trent Reznor turned fifty. By this time he had won an Oscar and been named the Chief Creative Officer for a subsidiary of Apple. Moreover, he had gracefully transitioned from Industrial Rock renegade to a venerable artist working at the intersection of composer and musician, Experimental and Pop. Between 2016 and 2018, Nine Inch Nails would release three products, all born out of a dialogue partially between Reznor and Ross, but mostly between Reznor and Reznor. The first two of these releases -- “Not the Actual Events” and “Add Violence” -- were sold as EPs (“Extended Plays”) and did not eclipse thirty minutes in length. “Bad Witch,” the final piece, is just six songs and thirty-one minutes long. It was marketed as an album largely because that format afforded the band and the label more promotional benefit on streaming services. In truth, all three of the releases are as considered and whole as any album but as succinct as most EPs. The fact that the first two are considered EPs is an unnecessary distinction.

Conceptually, these three releases are vast and deep. They were also highly intricate products, coming with hidden lyrics and elaborate packaging. “Not the Actual Events” famously included a mysterious black powder and label warning in its vinyl jacket. Further, the ideas that Reznor and Ross were contemplating are not for the faint of heart. According to Reznor, on the first EP, the band is considering the shame and viability of self and of ego. When looking for problems, Reznor starts from within but then wonders if he is even real. On the second release, the band turns its glare outwardly, decrying the regressive, insular culture that has led to our cultural and political doom. The theme for the finale was apparently discussed and agreed to at the outset. But then, on the heels of “Add Violence” and amid peak Trump America, Nine Inch Nails reconsidered. On “Bad Witch,” the finale, the band goes from masochistic, to cynical, to downright nihilistic. “What if none of this contemplation and desire to make things better matters,” they wonder. “What if humankind is just a mistake, a mutation, or a meaningless simulation?” There is something decidedly mature and impressive about pausing in between records to consider the original thesis. In that pause, NIN avoided redundancy and something pat and convenient in favor of something headier but even darker. If America in 2018 is the plot of “Bad Witch,” however, David Bowie’s passing is the unmistakable subplot.

Both “Not the Actual Events” and “Add Violence” feature five tracks. Both also include one, unmistakable single wherein Reznor and Ross prove that they are still eminently capable of carving verses, bridges and choruses out of the sturm and drang. “Add Violence” is the more experimental of the two, culminating with an eleven minute track that degrades a programmed loop fifty-two times until the music completely disappears. The two EPs, though divergent in perspective, are musically relatable. “Bad Witch,” however, sounds like something else altogether.

Like the two previous EPs, “Bad Witch” opens with a Pop stunner. “Shit Mirror” is a buzzing sprint, complete with handclaps and a megaphone. It sounds not unlike the best music that TV on the Radio was making in the late 2000s, both exhilarating and unlike what one might expect from NIN. It is catchy, fast and nuclear in its cynicism. The rest of the album is even darker, and bears no concern for Pop music. Of the following five tracks, two are instrumental, and both are set in a psychological dungeon that is often unnerving and always overwhelming.

“Ahead of Ourselves” is built upon the rhythm of some overworked printer or scanner, making file after file. With occasional bursts of noise, the singer chants the titular chorus, reminding us that -- no, we are not evolved -- we are millimeters away from being knuckle-dragging animals. The next track, “Play the Goddamned Part,” manages to be more frightening, without saying a single word. Over the sound of explosions and machines clattering, Reznor picks up a saxophone and explores various bruising tones that evoke something between Free Jazz and Eno-era Roxy Music. David Bowie, who was famously produced by Eno and also played the saxophone, serves as the subject and supporting actor in all of the songs that follow.

“I’m Not from This World” is the second instrumental, and sounds like windshield wipers battling a shit storm in a David Lynch movie. It is affecting more than it is effective. Surrounding it are the two songs wherein the singer croons like the Thin White Duke. On “God Break Down the Door,” Reznor’s deeper vocal register is paired with fog horn sax and surprisingly pert, 90s dance beats. The combination is most unusual, but sublime in the way that Free Jazz can be. You have no choice but to surrender to it. And on “Over and Out,” the album’s closer, the singer goes even deeper, crooning “time is running out” over and over before a swirl of alarms go off for the last three minutes of the song.

While nearly all of the 2016-2018 trilogy is compelling, a good deal of it is also unpleasant. If evaluated simply on the basis of listenability or song craft, more than half of the tracks would suffer. Several songs are wantonly experimental, testing the limits of pleasure. Others seem to promise a melodic payoff, only to then pull the carpet out from under at the chorus. On the whole, the ideas are probably better than the songs. However, the sonic adventure is thrilling and the intellectual journey pays off, if you are willing to submit. As carrot to their sticks, Reznor and Ross serve up one banger per record and tease enough ecstasy to keep the handcuffs on. Ultimately, you consent because you trust the artist that every decision is purposeful.

Had these three releases been conceived as a single, sprawling album, I suspect it might have failed commercially and critically. It’s simply a lot to take in and much of it is sensorily and conceptually overwhelming. Taken individually, however, you can imagine the larger movie. To say that Nine Inch Nails make cinematic music is to state the obvious. It is, in fact, literally true. More than a composer for film, however, Trent Reznor is undoubtedly the closest thing in music to a film director. He is not content making songs or albums. There are scripts and there is character motivation and there is photography and themes and settings and costumes in everything he does. Every movie he makes may take place between midnight and 4am. They may all be set in dungeons -- of sex, horror, or the mind. They may all be about seduction and addiction. They might believe in nothing or everything. But each time out, he performs the movie differently. Trent Reznor was always an artist, but, in middle age, he became an auteur.

For decades I was reluctant to either see or hear the distance between “Pretty Hate Machine” and “Bad Witch.” Candidly, I’m glad I skipped some of the journey. I was likely spared some terrible fashion choices, hysterical poetry journals and, possibly, some serious pain. But I am grateful Trent Reznor took each step. And stopped in between to consider the next one.