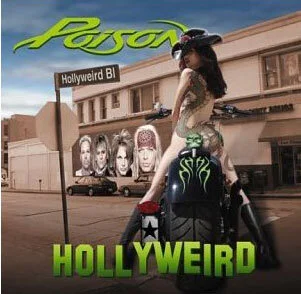

Poison “Hollyweird”

In the mid-1980s, sex education for pre-teens was hard to find. It was extra difficult if you did not have an older sibling or if your parent’s didn’t own a copy of “The Joy of Sex.” You could stay up past midnight and turn on HBO or Cinemax and hope for a glimpse of fornication. Or you could wait until summer and listen to your camp counselors share stories that you did not fully understand but pretended to. Or, like most American pre-teens in 1986, you could just watch MTV and wait until they played Poison’s “Talk Dirty to Me.”

Seemingly out of sheer necessity, the universe manifested Poison for hormonal twelve year olds. They filled that massive void between Motley Crüe (too old and too heavy) and GNR (possibly genuinely dangerous). Their two frontmen -- Bret and C.C. -- looked somehow both like swimsuit pinups and muscular Rock stars. Their music was cartoon Metal, closer to Pop or Rock than to Metallica or Iron Maiden. And, perhaps most importantly, in their words and their image, they signified adolescent sex. When Poison came on at a middle school dance, half the kids would squeal in delight, half would howl and a few outliers, having already discovered The Cure, would groan and shrug. Not being in that last camp, I was uncertain if Poison made good music, but I was dead certain that whatever they were making greatly resembled sex.

The sights and sounds of “Talk Dirty to Me” involved cars, basements and people screaming for more. Whatever it was, it sounded fast and urgent. In my mind, Kelly Bundy from “Married With Children” was also probably involved somehow. And, to state the obvious, it was dirty but simultaneously awesome. At the time, us pre-teens could only imagine what the reality was and what it all meant. So, for a year or two, all we was Tom Cruise and Kelly McGillis in “Top Gun,” late night cable fare and Poison. A good sex education it was not.

In a short time, we grew up. But Poison did not. They kept making the same four kinds of songs. The ones about hot sex (“Talk Dirty to Me”), the ones about heartbreak (“Every Rose Has its Thorn”), the ones about broken dreams (“Fallen Angel”) and the vaguely existential ones (“Something to Believe In”). Between late 1986 and 1991, that formula made them an enormously popular band, selling over fifty million albums and scoring a half dozen top ten hits. At the time, in the high days of Hair Metal, MTV and scandal television, it all seemed perfectly normal. But now, many years later, listening to Poison is kind of a chore. Even the best of it is not very good. Bret Michaels, pretty as he was, was a terrible singer. And the music has no fury. The loud songs sound like the used parts of The New York Dolls that had already been picked over and rejected by Kiss and Motley Crüe. Their cliches are tired and silly, even be pre-teen standards. There’s no video evidence that suggests they were a revelation in concert. Trust me — I searched. By almost any objective measure, Poison was kind of terrible.

However, against all odds and probably any merit, the band has persevered, remaining oddly relevant decades later. It makes little sense. Yes, Bret and C.C. were nice to look at. But so were Axl, and Sebastian Bach, and Tommy Lee and that dude from White Lion and the Nelson brothers. And yes, Poison imprinted teen sex upon Generation X. But, not more so than Madonna or Prince. And, sure, I guess the band had a knack for singalong choruses. But, compared to other popular, hard rockers of their day -- AC/DC, Aerosmith, Bon Jovi -- Poison sounds dull. So, what was it then? How did Poison survive?

The short answer to that last question is: they almost did not. At the 1991 MTV Video Music Awards, C.C. Deville famously and drunkenly played the opening lead to the wrong song while Bret, Rikki and Bobby stopped and stared. Host Arsenio Hall vamped and tried reintroduce the band and the song, hoping that C.C. would get the hint. But it was too late. Viewers caught a rare moment of dead air, wondering if they were watching an early example of reality TV or just an awful high school battle of the bands. It ended up being more of the former, though by that point, Poison did not sound a whole lot better than the latter. That same night, Bret and C.C. came to blows. And, within months, C.C. Deville was no longer a member of the band.

If C.C.’s departure wasn’t the fatal blow, Grunge easily could have been. Since 1993, Poison has had exactly zero platinum selling albums and exactly zero top forty hits. With the arrival of Pearl Jam and Nirvana, their species was almost rendered extinct. But they still survived. They survived the egregious excesses. They survived various addictions. They survived critical and commercial rejection. They survived Bret’s lifelong battle with Type 1 diabetes. They survived Bret’s brain hemorrhage and the hole in his heart. They survived his Ferrari crash. They survived the plastic surgery and the terrible fashion decisions. They survived while releasing just three (studio) albums in the last twenty years. They survived in spite of a front man who cannot reliably sing. Decades later, they’ve survived all of it and continue to tour arenas and state fairs to unfathomable numbers of adoring fans.

In retrospect, their endurance is not as illogical as it might seem. Poison survived and flourished on the basis of a rare combination of shamelessness, deviousness and politeness. When they got too old to fight on MTV, Bret and C.C. became reality TV stars. Bret pretended to fall in and out of love for nearly a decade as cameras rolled. Meanwhile, C.C. got sober, rejoined the band and gave fantastic, wide-eyed interviews to anyone who asked. Bret, in his second career as an aging, but still pretty, TV personality, was always polite and extraordinarily charitable on camera, while winking at every single lady in the audience and to the horn dogs back home. Well into middle age, he kept his hair long, his bandanas on, his skin tan, and sported a Cheshire Cat grin that seemed age inappropriate but also entirely familiar. He was the very good boy who did very bad things. But, he also did very good things for very good causes.

Somewhere at the bottom of the journey, with no functional band to speak of and few musical prospects, Bret Michaels wrote, directed, starred in and soundtracked “Letters From Death Row,” a movie co-produced by his friend Charlie Sheen. Rarely has a film’s title so aptly described the state of affairs of its maker and its star. The movie barely saw the light of day and left Poison and its frontman at a career crossroads.

Over the next ten years, though, Bret Michaels found his dual callings. In 2005, he leaned into his Western Pennsylvania populism and made an overdue turn just past Mellencamp and towards Country music. Both “Every Rose Has Its Thorn” and “Something to Believe In,” always had a Country heart, even if their cliches sunk below Nashville’s cheapest songs. And Bret, clad in his red, white and blue, was a natural for the increasingly contemporary Country format. Although the album was not a hit, it reintroduced him to the audiences that would eventually buoy the third act of his career.

Additionally, in 2007, Bret stumbled into his other, most natural occupation -- reality TV star. Over the next decade, on “Love of Rock,” “Celebrity Apprentice” and other lesser shows, Bret made his name all over again as a telegenic, simple, vaguely illicit asset. These star turns, alongside his dalliance with Country music and his steadfast adherence to the fashion of his 80s, helped resurrect Poison’s career in the 2010s. Amazingly, Bret and his band hadn’t really didn’t change much at all. They did not make a whole lot of new music. They looked and dressed the same as they had twenty five years earlier. They didn’t sound much better or worse. All they did was stand on the shoulders of Donald Trump and wait for their aging fans to line up alongside the future President’s new fans. That affiliation, which hardened into loyalty, would serve Poison well. Eventually, Bret Michael’s bandanas matched the red baseball caps in the crowd.

In between their lowest point and their red wave, Michaels and Deville reunited. Although the guitarist rejoined the band around 1996, it was not until 2002 that they put together enough material to complete a new album. That album, “Hollyweird” is a singular moment in the band’s discography when they were stuck between the comfort of the familiar and the need to be reborn. At the time, Poison was without a record deal. Hair Metal was no longer popular and was not yet ironically or nostalgically popular. Its voluminous void had been filled by Hip Hop, Electronic Music and Nu Metal — each of which portended disaster for Poison.

Simultaneously, Pop and Punk had collided in the forms of Green Day and Blink 182. And the seeds of Emo were creeping into the mix through bands like Fallout Boy. Newly sober C.C. Deville, who had always leaned slightly towards New York Punk, offered an alternative to Bret’s cheap, Hollywood shtick. With both parties desperate for relevance, they entered the studio hoping that they could balance fan service with some new, compelling idea.

Unfortunately, the results proved to be neither fish nor fowl, nor some interesting hybrid. Released modestly on their own indie label, “Hollyweird” has some of the charm of a fledgling garage band. But it also suffers from a similar lack of quality. By this point, and without the aid of studio trickery, Bret’s voice was a liability. When he went low, he sounded coarse and the top of his range was the basement for most other lead singers. C.C. sounded unsure of whether his guitar was meant to chug along like a Motorhead cover band, whether it should sear like a Hair Metal guitarist or whether it should tighten up into Pop Punk. Stuck at the very bottom was Rikki Rocket, who was often mixed so far back into the songs as to sound irrelevant. Some of the fault surely goes to the producer. But the lion’s share goes to the songwriters, who, in 2002, did not sound capable of either evolving or honoring their past.

From the very first notes of the title track, you realize that this version of Poison is all treble and little bass. They sound more taut, but less tight, than their 80s selves. The guitar has a squeal about it more than the woozy hook of C.C. imitating Johnny Thunders. There is a whiff of Emo and Nu Metal in the sound but it falls short for the simple reason that the songs lack a useful hook or melody or rhythm. “Hollyweird” is a bad enough title but, possibly, an even worse way to open an album that should have been a celebration.

For the most part, “Hollyweird” sticks with Poison’s tried and true creative themes: hot sex, broken dreams, heartbreak and something vaguely existential. “Get Ya Some,” about a girl who’s like a loaded gun but who also (fortunately) has a friend who’s game for anything, is of the first variety. It’s on brand, Rikki gets to play some cowbell and C.C. sounds a lot like his former self. It’s by no means a good song, but it’s only embarrassing in the way that most Poison songs are.

“Shooting Star” and “Wishful Thinking” are back to back sequels to “Fallen Angel” that do nothing to update the idea or the song. And “Devil Woman” tries to channel both The Stones and AC/DC in its dark, bluesy misogyny. Unfortunately, Poison isn’t even a fraction of those bands on their best day. It’s distasteful and lacks any of the melody or humor required to even marginally redeem it. In the end, all we are left with is harmonica, plodding rhythm guitar and a lot of bile.

While the album does not have any songs that signal some former or future greatness, there are moments that reveal a spark. On “Emperor’s New Clothes,” C.C. works out a fast, shrill Punk idea that resembles Sum 41 or, maybe, Linkin Park. It’s short and not fully realized but it’s an honest effort to break through. And, just two tracks later, C.C. returns with “Livin’ In the Now,” which seems to both be a tribute to clearheadedness and a strike against detractors and distractors. It goes by quick and the chorus is a terse whine, but it has the makings of earnest, competent Skate Punk.

Thankfully, “Hollyweird” is brisk. Thirteen tracks in forty-two minutes. And, though it briefly experiments with Punk, it soon returns to the safe harbor of blunt, kind of sloppy, kind of competent Rock. On the record’s second half, Poison rediscovers a glimmer of their loadstar. On “Wasteland” they pretend they have something incremental to add to GNR’s “Welcome to the Jungle,” but they struggle to conjure any of the menace or delight. Out of ideas, they almost save the song with an above average C.C. solo and some “oohs” and “ahhs” to cover for Bret. It sounds like third rate Guns N’ Roses, which, honestly, is probably the very definition of the band.

The album closes with “Rockstar,” a radio single that followed a truly awful cover of The Who’s already awful “Squeeze Box.” “Rockstar” is the closest thing to a “keeper” on “Hollyweird.” C.C. does more than chug along, waiting for his solo. He constructs a riff and lets it set in. And although Bret doesn’t add much melodically, his homesickness sounds sincere and he lands the big chorus. Additionally, it is the one song on the album that sounds like it has been properly mixed. You can feel the drums and bass. And the vocals don’t try to shout out the guitar. It sounds like a band who, in 1986, could have opened for Ratt or W.A.S.P. at the Whisky. Maybe they would have even gotten a record deal. Who knows?

The fact that Poison had a number one hit and platinum-selling albums is not unique. Plenty of less talented artists have bumped into a chart-topper on the basis of luck, timing or good looks. What makes Poison special is that, in spite of their dearth of talent and their meager catalogue, they have endured as both a band and a brand. Some part of this is Bret, the pretty, un-killable hustler from Pennsylvania. And some part is C.C., the big-hearted, broken, ham from Bay Ridge. Some of it is having the right look in the right place at the right time. Some of it is their cartoonish simplicity. Some of it is Trump. But most of it resides in the middle school dances of 1986, where kids were thinking things they did not totally understand but which they felt completely. Even when they sounded different and looked older and sillier, Poison always had some of that.