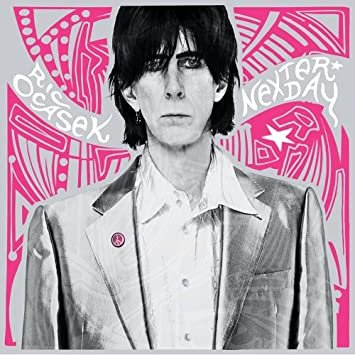

Ric Ocasek “Nexterday”

Though most of us associate “New Wave” with the synth-laden, dayglo Pop of the early 1980s, there, of course, have been many “New Waves.” In the 1950s, there was the French New Wave of cinema, which brought us Truffaut, Godard and other trailblazing “auteurs.” There were also Italian and Japanese New Waves, inspired by the movement in France. There was the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, which combined speed and horror with music that previously was just very Hard Rock. And then -- yes -- of course, there is the most famous “New Wave” — the semi-computerized, fully stylized Pop music of the late 1970s early 80s, which can itself also be divided into two fairly distinct genres.

The first phase of that New Wave was born just outside the shadows of Punk, and was characterized by a preponderance of synthesizer and an artfulness that was alternately romantic and nervous. The second phase grew up on the shoulders of MTV and traded art for fashion. By the mid-80s, the traces of Punk were no longer apparent in New Wave. It grew prettier, lighter and more disposable. By the mid-80s, New Wave was almost the opposite of nervous. It was carefree.

The poster children for the second New Wave were likely Duran Duran, who dominated the Pop charts from 1981 to 1985. They sounded great and looked even better on MTV, where they sailed, wore pastel tank tops and cavorted with women who were made up like exotic animals. The poster child for the first wave was probably Debbie Harry of Blondie, who looked like a Warhol starlet and who also came out of New York’s CBGB’s Punk scene. She wore ripped shirts and dropped her “R’s” while her band figured out what The Clash might sound like if they were actually a Girl Group.

But really, there is only one homecoming monarch -- one person who personified both phases of “New Wave” -- the artful Post-Punk version and the stylized Pop version. And it was not Simon Le Bon or John Taylor or Debbie Harry or Gary Numan or David Byrne, for that matter. It was the guy who looked (and sounded) exactly like the lovechild of Joey Ramone and Tom Verlaine. The six foot, four inch singer, songwriter and guitarist who wore skinny ties, oversized blazers, dark glasses, and a dangling earring. The guy who sang with that nervy, off-kilter disaffect which was, by any reasonable standard, closer to Lux Interior of The Cramps or Peter Murphy of Bauhaus than to the guy from The Knack. He didn’t talk much. His hairstyle was, for lack of a better description, a jet black mullet with bangs. He looked positively malnourished. But, his songs were completely infectious -- short and bittersweet, though more sweet than bitter. And, from 1978 to 1985, he was among the biggest Rock stars and Pop stars in the world. His name was Ric Ocasek. And his band, of course, was The Cars.

Ric Ocasek didn’t start out so weird. After leaving college and relocating to Boston, he and Benjamin Orr formed the band Milkwood in the early 1970s. Milkwood made gentle Folk Rock with three part harmonies. They sounded almost exactly like Crosby Stills and Nash but without all the countercultural histrionics. They were vaguely “groovy” but they did not groove. Their lone album, “How’s the Weather,” is actually quite lovely, suggesting that its two founding members were full of talent, but in no way indicating their future direction. After one unsuccessful release, Ocasek and Orr reconstituted first as Richard and The Rabbits, then as Cap’n Swing, and finally, with the addition of former Modern Lover, David Robinson on drums, as The Cars.

Where Milkwood was all soft edges, The Cars, like Ocasek himself, were all sharp angles. Their songs were economically Punk but philosophically romantic and stylistically Pop. They were, along with Blondie, perhaps the first retro-futurists to make their way onto the radio. Structurally, their music resembled early Rock and Roll. But, vocally, Ocasek and Orr borrowed from Tom Verlaine’s pinched, low tenor style and poetic dispassion. In their sonic economy, The Cars were perhaps most like The Ramones, but without all the noise and with a hint of the Ivy League.

Beginning with “Just What I Needed” and “My Best Friend’s Girl” in 1978, The Cars went on a historic chart run that included over a dozen Top 40 hits and five consecutive platinum selling albums. Their songs had a factory-like production quality — like they were stamped out quickly and with an inordinate degree of quality and consistency. Every Cars’ single featured Greg Hawkes’ jittery synthesizers alongside Robinson’s pert rhythms and Ocasek and Orr’s left of center hooks. It was a formula that they perfected early on and did not mess with for their entire career. Though Ocasek looked odd, and though The Cars dressed and sang like art students, formally, they were completely predictable.

But also, they were completely delightful. “Shake it Up” and “You Might Think” were just as perfect as “It’s All I Can Do” and “Good Times Roll,” which were as flawless as their first two hits. They even had a formula for their ballads, which simply took the same elements as the uptempo numbers, dialed up the synths and the reverb, dialed down the guitars and then switched the band from thirty three and a third to forty five rpm. The results were, perhaps, even better than their faster paced siblings. “Since You’re Gone” is a timeless, wistful slice of New Wave. “Moving in Stereo” is the soundtrack for any fantasy involving Phoebe Cates (which, I suspect, is at least half of the fantasies in the world). And “Drive,” with its cinematic, melodramatic video, became the biggest hit of their career in 1984.

America loves cars. And America loved The Cars. On the surface, it really was that simple. But, just beneath the pop sheen was all of the intense labor involved in keeping the factory operational. It involved balancing two lead singers -- Ocasek and Orr -- with distinctly similar styles. It involved making high concept videos that were “conceptual” or “kooky” even, but never weird. It required Ocasek to lie about his age, shaving five years from the evidence of his birth certificate. It was a combination of being everywhere -- on the radio, in stores and in concert -- but never being especially accessible. Even when Ocasek married Paulina Porizkova, one of the most famous models in the world, The Cars’ frontman kept his sunglasses on and his mouth shut. It’s not so much that The Cars were opaque as they were a tightly composed sound and image. Everything they needed to say could be communicated in less than four minutes.

While The Cars remained hermetically sealed, Ocasek freelanced to exercise his eccentric side. He released two solo albums during the 1980s and produced music for Suicide, Romeo Void, Bad Brains and Lloyd Cole and The Commotions. And though his production style was informed by his main gig, his side hustle allowed him to keep one foot in the other side of weird. Ultimately, though, that pull became the undoing of The Cars. Ocasek loved to record music in the studio. Everything else, not so much. And so, after “Heartbreak City,” from 1984, when they were at the peak of their fame but while New Wave was just beginning to wane, Ocasek started to think about life after The Cars. He’d tired of life on the road and the endless, dizzying cycle of writing, recording and touring. Meanwhile, his relationship with Orr was straining and his career as a producer and A&R man was ascending. And so, in 1988, after the release and lackluster performance of “Door to Door,” The Cars went on a hiatus which, at the time, was thought to be permanent.

Ocasek’s career after The Cars included a series of charming, lower stakes solo albums in between gigs as a “record guy.” For most of the 90s, he was employed as a talent scout for Elektra Records and as a prestigious super-producer for hire. Like practically no one else, he knew how to balance guitar and synthesizer, pop with art, and ideas with brevity. And he put those skills to great use throughout the decade — perhaps never more so than on Weezer’s debut (“Blue”) album. “The Blue Album” ostensibly gave Ocasek carte blanche to do whatever he wanted for the third act of his career. It meant that, in 1997, he could make a solo album with Billy Corgan and Melissa Auf der Maur, of the Smashing Pumpkins, and Brian Baker, of Minor Threat and Bad Religion. It meant he could quit his job at Elektra and simply make the records he wanted. It meant that he could produce albums for Le Tigre and Brazilian Girls.

It also meant that he could write poetry and paint and be a father and the husband of a supermodel. Though his bio claimed otherwise, Ocasek turned sixty in 2004. He had six kids from three marriages. He’d done it all and managed to stay weird on the inside. Sure, he’d trimmed the New Wave mullet an inch or two, and maybe he’d added some lines to his face, but he still hid under the shades and bangs. He still wore oversized tops, buttoned all the way up. And he still had that odd earring dangling. In contrast, by 2005, Blondie was a nostalgia act. David Byrne was much more high art than Pop. Sting made listless world music. And Duran Duran survived through the wonders of modern medicine and Totally 80s compilations. Ric Ocasek, it seemed, had won. He’d had his cake and eaten it, too. He was able to change directions before the wind changed direction. He was able to do the things that Joey Ramone and Tom Verlaine never could -- stay weird and thrive.

All of which makes “Nexterday” even harder to explain. Released in 2005, Ocasek’s seventh (and final) solo album was unlike anything he’d ever made before. It was weird in that he played most of the instruments himself. It was weird in that it favors a demo quality instead of his trademark studio luster. It’s weird in its sparking use of synthesizers. But, mostly, “Nexterday” is weird in how completely un-weird it sounds. In fact, I’d say it’s downright boring.

When I first listened to Milkwood’s album from 1972, I heard something that I had previously thought Ocasek was incapable of: dullness. It’s not so much that the songs were unpleasant or shapeless so much as they were tonally unvaried. The Cars, meanwhile, were consistent but never, ever dull. Their sameness somehow compelled foot tapping and hand clapping. But, thirty plus years after Milkwood -- after the fame and fortune and an album with Billy Corgan and at a time when he was free to make the weirdest music his heart desired -- Ocasek did the exact opposite.

You can still hear The Cars’ blueprint on “Nexterday.” The hooks are short, simple and played on repeat. The singer still projects from his brain more than his diaphragm. And his words -- even when they read as excitable -- ultimately sound disappointed. On the other hand, the record sounds as though there was too much oxygen in the room. The studio sounds like its doors have been left open. The synthesizers are used sparingly, and purely as decoration. Ocasek never sounds nervous. He sounds patient -- relaxed. Or maybe slightly depressed. And, while he is a great writer and singer and an adequate guitarist, he is barely a drummer. And so, there are no toe-tapping or hand-clapping moments. “Nexterday” is an album that seems to be unaware that cars used to come with five gears. It is perpetually stuck somewhere between second and third, occasionally downshifting but never racing.

Of the eleven songs on “Nexterday,” there is not much that distinguishes itself. Everything has the same template -- a slight hook of the guitar, played on repeat and without any variance, before a slight turn into a listless chorus. They are all steady. Too steady, in fact, as though Ocasek is playing to a metronome. “Silver” is nominally different in that it stays in minor chords and is about his former bandmate, Benjamin Orr, who died in 2000. It’s a heartfelt and generous song, for sure. But, if I knew nothing of the backstory, I would probably have just ignored it. Or rather, it would have simply passed me by. Like most of the album, it sounds like music made under the influence of antidepressants, but before the proper dosage has been figured out.

The lone surprises of “Nexterday” -- and they are truly quite modest -- arrive at the end of the album. “Please Don’t Let Me Down” is closer to a true ballad, with a wash of synthesizer and the bass in front of the guitars. Whereas the rest of the record would not even suffice as background music, this one has a gentle and immediate charm. And even though it sounds nothing like Ocasek’s music with Milkwood, it’s similarly lilting and inoffensive. It’s followed by the album’s closer, “Let’s Get Crazy,” which is, of course, anything but crazy. It is, however, a sturdy piece of Jangle Rock where Ocasek pushes the guitar and drums to the fore and separates the hook from the tiredness of his vocals. The contrast works. Or maybe, after an album lacking in variance, the contrast is simply welcome. In either case, “Nexterday” ends better than it started, shifting into fourth gear, without ever getting weird or nervous or infectious or any of the other things that Ric Ocasek was known for.

In the years that followed, Ocasek downshifted again. He took on fewer production gigs. He stopped making solo albums. He resolved grievances with his former bandmates. In fact, in 2010, the remaining Cars returned to the studio and reunited for one final, “good enough” album and a North American tour that was routinely described as “disappointing” and “unenthusiastic.” Though he’d return to help make one more Weezer album, Ric Ocasek was done. And The Cars were whatever comes after “done.”

In 2018, the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. That same year, Ocasek and Porizkova separated. And then, in 2019, while recovering from surgery, Ric Ocasek died of natural causes. He was seventy five at the time, though publicly, he claimed to be just seventy. Obituaries talked about the Pop star who’d redirected the mainstream to the left of the dial; the guy who’d figured out the balance between loud guitar and louder synthesizer; the guy, without whom, there’s no Weezer or Smashing Pumpkins or The Killers or The New Pornographers or The Strokes. Ric Ocasek left behind six children, dozens of unforgettable songs and a slew of great albums that he produced. But “Nexterday” was a man completely unconcerned with legacy. That’s the best I can say about it.