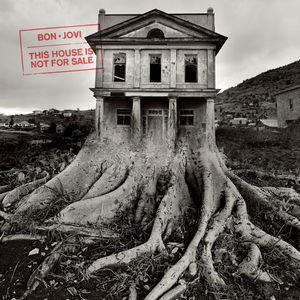

Bon Jovi “This House Is Not for Sale”

We were young — teenagers. But, even then, we knew. We knew that Poison kind of sucked and that Mötley Crüe was trouble and that KISS was over. We didn’t know algebra or who would win the Cold War or how to drive a car, but we knew well enough. And we knew that Bon Jovi was different — and very important.

Bon Jovi were the first ones who put it all together. They understood how synthesizers had worked for Van Halen on “Jump” and how the ballad had worked for Crüe on “Home Sweet Home.” They knew that hair was important but make up was less so. They understood that, while cowboys liked danger, they were not actually dangerous, and that New Jersey was for underdogs, and that motorcycles signified freedom. They may have known exactly nothing else, but they knew what we knew. And that was way more than enough.

“Runaway,” from 1984, was the precursor — a fluke really. It was just a fancy demo, recorded by Jon at his cousin’s New York studio. There was no “Bon Jovi” when he wrote the song in 1981. There was no album. But then, WAPP — the radio station that Jon had been hired to write jingles for — started playing the song. Other stations followed. In no time, Jon Bongiovi Jr, Richie Sambora, Tico Torres and David Bryan were Bon Jovi — the biggest Rock band in the world.

Three years after “Runaway” snuck its way onto airwaves, Bon Jovi released “Slippery When Wet,” the album that changed everything. “You Give Love a Bad Name” was a defiant, ballsy shoutalong, loud-as-fuck Rocker. It was not quite Metal, not quite Rock and definitely not Pop, but completely, insanely popular. Next came “Livin’ On a Prayer,” with its “whoa whoa” guitar and another shoutalong chorus and its no retreat no surrender posture whch did not — in any way — feel like a posture. And just when you thought they could not get any cooler, they put on their cowboy hats and spurs saddled up on their hogs and transformed into outlaws for “Wanted Dead or Alive.” It was a breathless run — three top hits. Two number ones. Topped off by “Never Say Goodbye,” the song that predicted “Every Rose Has Its Thorn,” “November Rain” and dozens of lesser, totally 80s power ballads.

Though it is their definitive album, “Slippery When Wet,” is only partially a “Bon Jovi product.” Desmond Child, who was well on his way to eclipsing Jim Steinman as Rock’s greatest maximalist, co-wrote four songs, including the two chart toppers. And Bruce Fairbain, who’d helped Loverboy discover the exact temperature at which synths and guitars could co-exist, produced the album. Child had an uncanny flair for the theatrical chorus. Fairbain knew how to make Hard Rock sound like Pop music. Add some leather pants and Jon Bon Jovi’s chest hair, and you had a Diamond-seller.

But, unlike Def Leppard, these guys were ours. In fact, they were from New Jersey, which meant that they were not just ours — they were mine! In 1986, at the age of twelve, four guys from not so far away, were the biggest, awesomest, hottest, most fearless Rock band in the world! Dads liked them. Moms loved them. Girls loved them. They were like Rocky and Dirty Harry and Jimmy Page and Christie Brinkley had melded to become a Rock band. What was not to love?

Bon Jovi’s greatness was so massive and so obvious as to be beyond question. “New Jersey,” from 1988, was almost excessive confirmation. The album contained not one. Or two. Or three of four. But five top ten hits, including two number ones (“Bad Medicine” and “I’ll Be There for You”). And though Glam Metal was ascending at the time and dozens of other bands were carefully studying Bon Jovi’s formula, none could replicate it. Aerosmith and Cheap Trick were older. Skid Row was just a pretty face. Poison still sucked. Guns N’ Roses were from LA and were something else altogether. Of all those Hard Rock bands with Hair, I remained convinced that Bon Jovi reigned supreme.

By the end of the 80s, my attention naturally turned elsewhere. If I was watching MTV, it was only for “120 Minutes.” If I was listening to the radio, it was on the very left of the dial. I’d discovered Punk and then Post-punk and then Indie. And so, when Bon Jovi released “Keep the Faith” and “These Days,” I was aware, but not keenly interested. Plus, Bon Jovi was fine! They didn’t need me to help them sell ten million albums. I presumed that they’d outlast the imitators and survive Grunge and Alt. I had no doubt that they would not only persevere, but thrive. After all — they were Bon Jovi!

While I was looking away, though, some things changed. Jon cut his hair. Not short short. But shorter, closer to soccer mom than cowboy on a steel horse. The hits began to dry up. Slowly. Then surely. “Always,” from 1994, was the band’s last trip to the top ten. But, most of all, the band stopped being daring and weird. The formula they hatched on “New Jersey” — lots of chorus, not much else — began to solidify. And then harden. Their image — kind of glamorous, kind of Metal, good boys with a dangerous streak — coalesced into something broader. As the 1990s became the 2000s, Bon Jovi had become a middle of the road Rock band, only marginally distinguished by their trademark grit. They were easy to like and hard to hate. But they were no longer irresistible.

Nevertheless, Bon Jovi could still sell records — millions of them. “Crush", from 2000, and featuring “It’s My Life,” was still positively massive. But it was clear to anyone who was paying attention that things had shifted. In middle age, Jon had become a semi-serious actor. Richie, meanwhile, had become a semi-sloppy target for tabloids. They survived Grunge and then Alt. They had not imploded. But, while they were still immensely popular, Bon Jovi were only barely relevant. Their grit had become subsumed by nostalgia. Their fearlessness replaced with trite optimism. They had become something I never thought they’d be: boring.

Bon Jovi 2.0 emerged in 2005 with “Have a Nice Day.” Version 1.0 of the band had been built on Richie Sambora’s bluesy melodicism and Desmond Child’s maximalism. Sambora was the guy who married Heather Locklear and could get a little sloppy. And Desmond Child was the son of a Hungarian baron who wore a braided ponytail and facial hair swiped from NSYNC. 1.0 was about possibilities. Version 2.0, however, was stripped of that magic. 2.0 was about constraints — about limiting the downside. It was about Jon and John. Jon Bon Jovi was the coiffed, denim-clad, (filthy rich), middle-aged everyman, who’d married his high school sweetheart. And John Shanks was the uber-competent, lightly alternative writer and producer who wore a New York Yankees’ cap and had a boring goatee. The distance between version 1.0 and 2.0 was the distance between “Livin’ On a Prayer’s” bombast and “Have a Nice Day’s” politeness.

That chasm from bombast to politeness is the existential risk for all Arena Rock bands — the inherent conflict of producing anthems that are both universal and specific. Led Zeppelin succeeded because they were the first and the greatest of the Arena Rockers. U2 won out because they just wanted it more. Radiohead can do it because — well — they are Radiohead. But for every one of those stories, there are many more unhappy endings. Journey had “The Voice” but, frequently, not the songs. Foreigner had those eight essential singles but were soon relegated to power balladry. Van Halen had the highest highs and the lowest lows. More recently, there are the Foo Fighters and The National, both of whom are capable of greatness though equally likely to regress to a mean. High end arena rocking is hard work. And it’s nearly impossible to sustain.

So, in an effort to avoid the fall, Bon Jovi made a shrewd turn. For a season, between 2006 and 2008, they left the swamps of Jersey for that vast expanse between Nashville and The Heartland. “Who Says You Can’t Go Home,” featuring Jennifer Nettles, was a bonafide Country hit in 2006 and a harbinger of things to come. “Lost Highway,” the band’s tenth studio album, was more full-throated in its Americana, featuring appearances from LeAnn Rimes and Big & Rich. The album was only a modest hit, but it served a higher purpose — a bidding of farewell to MTV (and even VH-1) and a warm embrace of CMT and Fox Football Sunday.

The next phase of Bon Jovi — the third one — was the logical amalgamation of what had come before and what was necessary to survive into the future. They remained arena-sized, but whereas before there was volume and weight, there was no longer any heaviness. They were barely “modern,” but they were contemporary enough. And though they never went full Country, they doubled down on the “no retreat, no surrender” posture that was catnip for flyover states. Bon Jovi 3.0 was the opposite of unpredictable. They were absolutely not thrilling. They were not Jon and Richie’s band. They were Jon Bon Jovi and John Shanks’ band. They were the Bud Light of Rock bands. Ubiquitous. Football friendly. Venerable. Bland.

On the other hand, they were also reliable. Even as Richie’s life began to spiral. Even as the hits dried up. Even when years would pass between albums. Bon Jovi stuck around. That became their brand — the band that stuck around but never bottomed out. You might not love them. You might not even care about them. But they were almost impossible to hate. And any time they put out a record, you could rest assured that it would reach the top of the sales charts. Eventually, the were more ubiquitous than Bud Light. They were more like Coke. Or bottled water. They were a given. They just…were.

That’s the version of Bon Jovi that released “This House Is Not for Sale” in 2015 — the bottled water version. The version that still had Jon and Tico and David but which could no longer tolerate the variability of Richie Sambora. Through the years — through addiction and changing styles and less Blues and less Metal — Richie had remained Jon’s creative partner. That partnership ended sometime in 2013. In 2015 Jon Bon Jovi was a fifty-three year old philanthropist, aspiring NFL owner and — yes — Rock star. He’d emerged virtually unscathed — still married, still fighting the good fights, still iconic, if generic. Richie was no longer his ideal running mate. John Shanks was.

In the same way that Jon had refined his image, Shanks had refined his sound. John Shanks’ songs were exceptional for their economy — they were linear and predictable. His verses tend to be simple and melodic, but unobtrusive. Their job was to set up the choruses, which did the heavy lifting. Shanks choruses are big, loud, fuzzed out and hooky. Guitar solos are almost superfluous in Shanks’ hits. Synths exist as decoration rather than as melody or, even, ambiance. Bridges are employed sparingly and strategically. As with Desmond Child’s biggest Rock hits, the choruses are meant to be shouted by the entire band, in unison. Unlike Desmond Child’s best songs, however, there are no surprises in a Shanks’ hit.

By 2015, Shanks’ signature had come to resemble that of the Foo Fighters — few chords, lots of rhythm guitars, heavy-hands on the drums, mid-tempo in the verses, ecstatic in the choruses. On top of that chassis, he would add chiming lead guitars that were much closer to The National by way of Coldplay by way of U2 than they were to Richie Sambora’s Blues. And, somewhere in that mix, was the very familiar voice of Jon Bon Jovi, which — in middle-age — resembled that of Bryan Adams, but without any of the range or character.

Ultimately, that is the lone surprise of “This House Is Not for Sale”: Jon Bon Jovi’s voice. What had for years been propped up by gargantuan choruses, subtly-awesome backing singers, bravado and rasp, was revealed to be a terribly lacking instrument. I’m not sure if he lost it or if he ever had it to begin with. The lead singer on “Slippery When Wet” sounds a good deal like the guy on “This House.” But whereas that twenty-something singer went for broke and had Richie Sambora right behind him, the fifty-something version is more naked — and exposed. To my utmost surprise, it turned out that Jon Bon Jovi was always a hell of a Rock Star but never that much of a singer. This literally never occurred to me in 1986. But, in listening to Bon Jovi’s first post-Sambora record, it was all I could think about.

Well, almost all. Ultimately, “This House” is a remarkably competent, big and, frequently contemporary sounding album. Its consistency and efficiency are noteworthy, but its style and ideas are generic. The album has three ostensible messages: (1) Don’t Back Down. (2) United we stand but divided we fall. And (3) Love the past but hope for the future. It’s a rare trick that Bon Jovi is trying to pull off in 2015 — balancing deep nostalgia and grit with wide-eyed optimism. It’s far less critical than Springsteen, but similarly progressive. It lacks the poetic ease of Petty, but shares some of its heart. It’s the sort of trick that can only be pulled off by an avowed liberal in a cowboy hat on a motorcycle.

If you remove Jon Bon Jovi’s vocals, much of the album could be confused for the Foo Fighters. And that is by no means a bad thing. “Living With the Ghost” is probably the best of the “Foo Jovi” numbers. It’s verses have a blood-pumping pulse and the chorus explodes like the soundtrack to an NFL highlight film about a linebacker overcoming great adversity. It’s familiar enough and enjoyable enough that I can forgive the hackneyed lyrical trick that I understood to be a no no since as far back as middle school:

Last night I had this dream

I saw a man wash his feet

In the church holy water

He worked up to his knees

From his arms to his neck

Said, "I'm in over my head"

He was crying trying to get some relief

Lord, I'm just trying to get some relief

I had this dream

That man was me

Can a grown man really do that thing where he describes a dream (one which has literally no metaphor or symbolism) and then reveals that the ghost in the dream was not, in fact, a ghost, but rather the singer himself? Is that lazy Shyamalan-ism still allowed when you’re fifty-three?

And yet, on some level, that’s the appeal of Jon Bon Jovi. The limitations of his voice serve its familiarity like the triteness of his cliches serve their accessibility. With Shanks sturdy hand at the wheel, Jon confirms that he’s still the same guy we fell for decades ago, but also that he’s also not so different from the other, best loved guys from the years since — Petty, The Boss, Coldplay, U2 and Foo Fighters.

The best versions of the formula manage to sound better than “formulaic.” “Roller Coaster” is a close — and pretty darn good — approximation of Jimmy Eat World’s “The Middle.” Measured in the verses and ecstatic in the chorus, it’s a completely banal idea, but Jon sells it. You believe that life is not a “merry go round” — that it is precisely what the title suggests. And you feel a little better knowing that, even though you already knew it and even though it’s also not true.

The album’s biggest outlier is its most derivative and its most compelling song. “Labor of Love” steals liberally from Bruce’s “Tunnel of Love” and Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game,” adding Jon’s pitched croon, which sounds not unlike Gwen Stefani. But, you know what? It doesn’t matter. The melody is pretty. The reverb and slide guitar are effective and — though he might sound a little silly — middle-aged Jon Bon Jovi sounds pretty credible on the subject at hand.

As for the misses, there are relatively few. And, even those are more “unexciting” rather than “terrible.” “Walls” is a gutsy dud — a sing-songy number about polarization, that sounds like Imagine Dragons when it should probably sound like Kenny Chesney. Its earnestness is a poor fit for “Modern Rock.” “Knockout” has a similar “we will force you to sing along with us” energy, but all of the “woos” and “boom boom booms” do not make up for an inherent lack of melody.

On the margins, though, “This House Is Not for Sale” is more good than not. And that is in spite of the cliches and the extraordinary limitations of its singer. It’s a testament to Shanks’ dexterity with “MOR” Rock and to Bon Jovi’s salesmanship that it works as well as it does. But, in its tension between extreme hope and complete settling, you can almost hear the cracks. The album and its singer are trying to hold an untenable position — that of the nostalgic progressive. Eventually, necessarily, something had to give.

What was subtext in 2015, became the central theme five years later when Bon Jovi released “2020,” an album unflinching in its support for BLM, Colin Kaepernick, the reconsideration of gun laws and the suffering of South American migrants. “2020” was the poorest selling album of Bon Jovi’s career, suggesting that fans prefer the more generic, Fox football version of the band to the political one. Musically, I might agree. But, personally, I’m with 2020 Jon. He’ll never be iconic again. But maybe he can be a little iconoclastic. Or maverick. Get out that cowboy hat and leather chaps, Jon. America still needs you.