Bad Company “Here Comes Trouble”

In 1992, a decade after they’d traded their sublimely gifted lead singer (Paul Rodgers) for Ted Nugent’s former frontman (Brian Howe), Bad Company were in the waning hours of their second sunset. But somehow, three decades later, I find myself more than a little impressed with their final salvo. It's not so much that “Here Comes Trouble” is exceptional—it’s absolutely not. But rather that it is exceptionally good. It is both what I expected—professional, middle of the road, twenty percent softer than Hard Rock—and also a complete surprise—melodic, pleasurable, immaculately recorded songs that locate the exact midpoint between Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is” & “Jukebox Hero.”

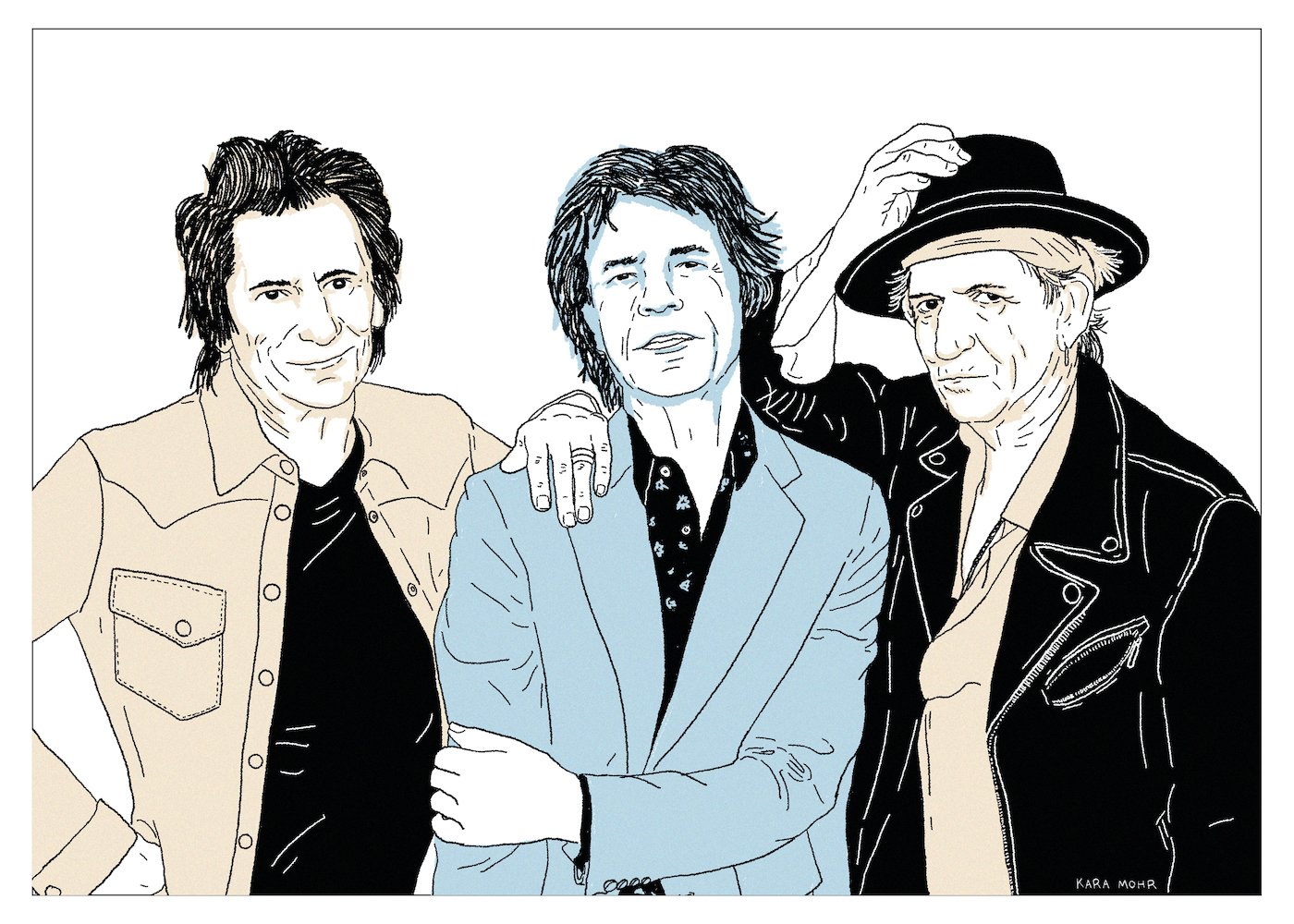

The Rolling Stones “Hackney Diamonds”

ChatGPT—can you make a song that sounds like “Start Me Up,” but a little faster? OK, thanks. ChatGPT—can you make it a little more Pop? ChatGPT—a little faster please. Can you also make Mick sound like he’s thirty? No—too young. How about forty-five? OK—great. Now — can bring the vocals up & make the beat snap more? Can you isolate Keith’s guitar & raise it up a bit? And can you clip all the highs & lows from the mix? OK, perfect. Now ChatGPT—can you find something Country-ish from “Some Girls” & do the same thing? Then just keep going & let know when you’re finished. Thank you ChatGPT.

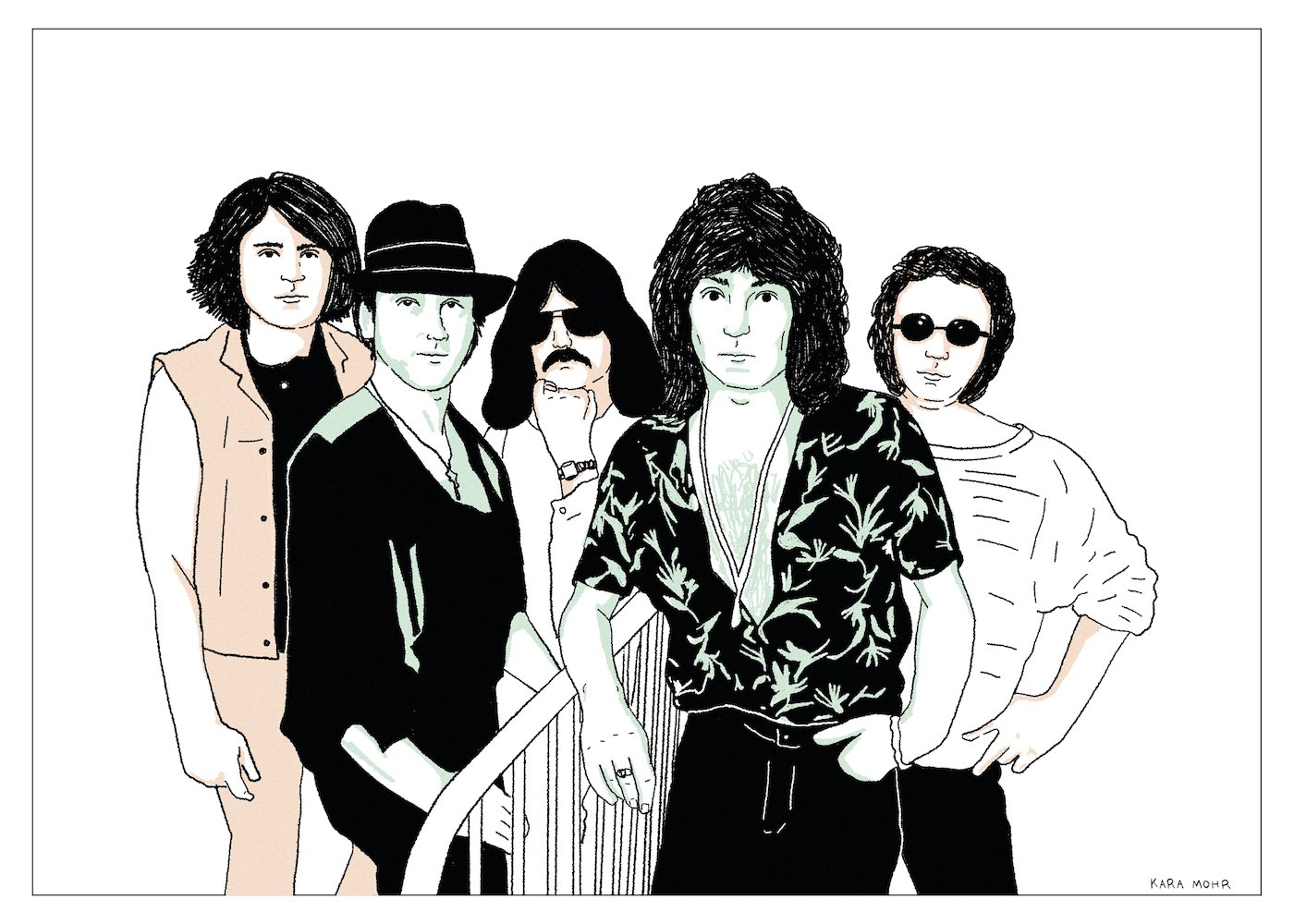

Blue Öyster Cult “Imaginos”

“Imaginos” is not really a Blue Öyster Cult album. Yes — it features the same five men who played on their beloved Seventies albums. But no — those five men did not write, play or record the album together. The name “Blue Öyster Cult” appears in name only, as a last ditch effort to see if the parties involved could recoup any of the significant cost sunk by their former drummer, Albert Bouchard. And yet, in a strange way, “Imaginos” is also the most Blue Öyster Cult album in that it was born from the band’s source material. While frequently indecipherable, “Imaginos” is oddly important in that its concept not only predated Blue Öyster Cult, but actually invented Blue Öyster Cult.

Deep Purple “The House of Blue Light”

In “This is Spinal Tap,” documentarian Marty Di Bergi reminds the band that their 1980 album “Shark Sandwich” had once famously received a review which read simply: “Shit Sandwich.” But in (cinematic) fact Spinal Tap were always loathed by the critics and “Shark Sandwich,” which featured “Sex Farm” and “No Place Like Nowhere,” was actually something of a return to form. Like “Shark Sandwich,” Deep Purple’s “Perfect Strangers” did not fare well with the mainstream press. In 1985, Rolling Stone printed a two star review that read like a one star review. Nevertheless, and like Spinal Tap’s late career hit, “Perfect Strangers” thrived commercially. But, if “Perfect Strangers” was Deep Purple’s “Shark Sandwich,” it follows that “The House of Blue Light” was their “Smell the Glove,” an ill-fated document of disunion that revealed a band spiraling into mid-life crisis.

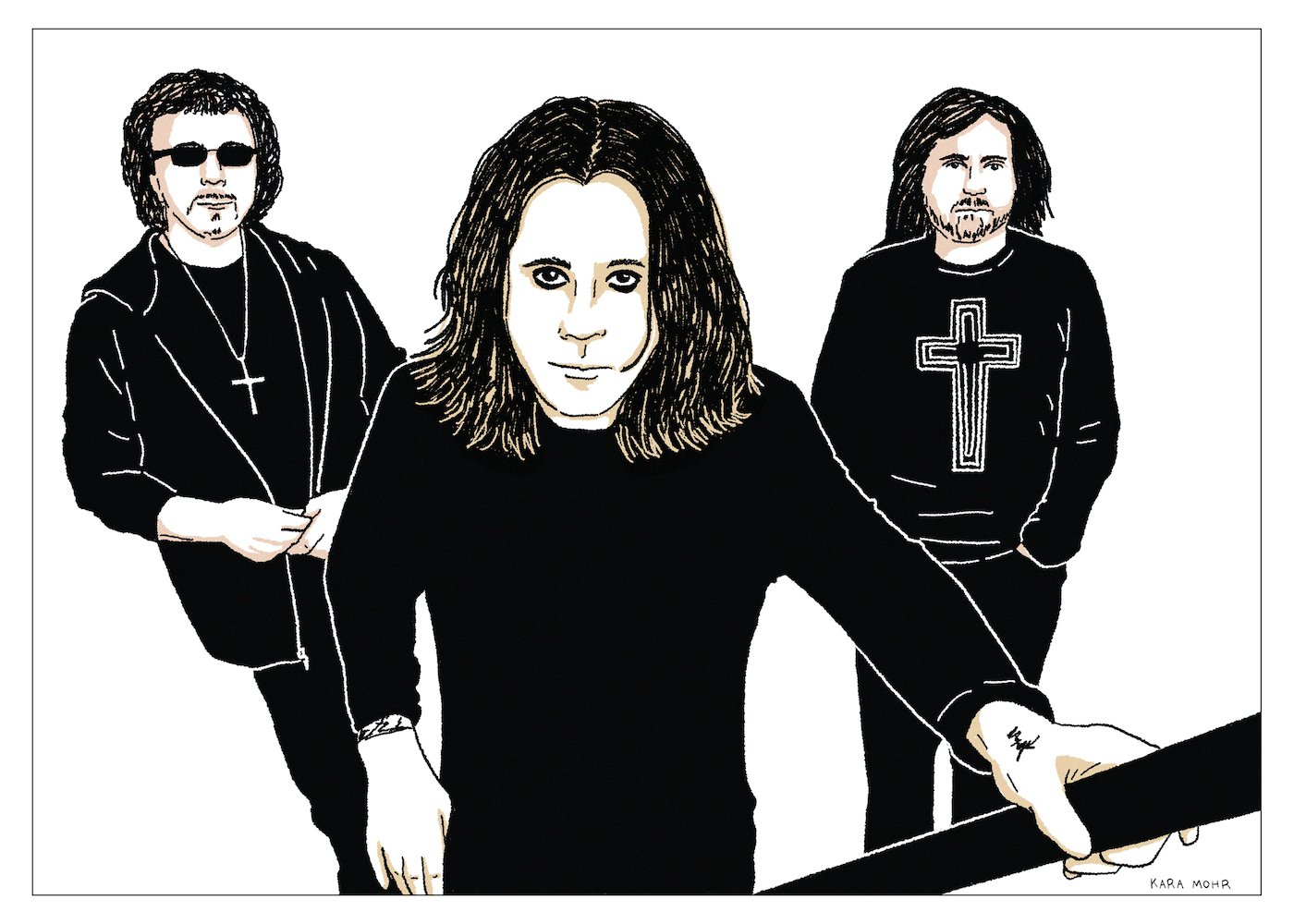

Black Sabbath “13”

Once upon a time, Black Sabbath were considered musical troglodytes — dumb, artless wankers, shunned by the cultural cognoscenti. Years later, even after many fans and some critics came around, they were still treated like drunk, possibly murderous threats. It was not until recently, long after Ozzy left, after Ronnie left, after most of the world had reconsidered them, that Sabbath settled into the realm of quaint, rich celebrity. They came to signify the excess and darkness of Seventies Hard Rock and the eventual convalescence from said excess and darkness. By 2013, Ozzy Osbourne was unimaginably wealthy. He was a reality TV star. He was a doddering, comical old man. And yet, despite the passage of time, despite the reputational rehab and despite Ozzy’s defanging, “13” is not funny — not for a single moment.

Huey Lewis and The News “Plan B”

The Nineties were a fallow period for Huey Lewis and The News. Following a decade wherein they released nine albums, the band mustered just two over the next ten years. His platinum-selling, chart-topping days were a thing of the past, but his transition from Heartland New Wave to aging Mom-and-Dad-core was both graceful and inevitable. In some ways it made much less sense that Huey Lewis was ever a bonafide Pop star and more sense that he was a charming screen presence who occasionally put out R&B albums. By 2001, at the age of fifty, Huey had finally achieved his pop culture destiny, settling into his rightful place as Bruce Willis’ less theatrically — but much more musically talented — cousin.

Bob Dylan “Together Through Life”

If Past Past Prime Van Morrison sounds like disgruntled Soul, and if Past Past Prime Leonard Cohen sounds like breathy Tao, Past Past Prime Dylan sounds more like Willie Nelson. It’s the sound of an artist working tirelessly, but with an air of retirement. The stakes are lower. There’s nothing to prove. And even if he had an agenda it would be swallowed up by his voice. That voice. The voice of relief and release. The voice of self-knowledge and self-acceptance. If you squint your ears, those post-”Time Out of Mind” records — from “Love and Theft” through “Tempest” — sort of blend together. The bands vary. Stories and settings change. But they share a common pace, range and — most of all — voice.

Peter Frampton “Now”

Frampton’s appeal was something like Xanax — it was a mild but neutered sensation. He possessed a rare capacity to elicit pleasure without the charge of Rock and Roll. Which is not to discount his talent so much as it is to explain why he was so positively vital in 1976 and so completely antithetical by 1977 — the year in which “Rumors” and “Never Mind the Bollocks” exploded with feelings. Amazingly, 1976 was also the year that the U.S. patent was awarded for Alprazolam — known commonly as Xanax. Yes — Xanax arrived at precisely the same time that Peter Frampton dominated airwaves and record store shelves. However, it did not take long for the effects to wear off and for everyone — including no doubt Frampton himself — to realize that we needed to actually feel the feelings.

Jimmy Buffett “Fruitcakes”

Buffett’s eighteenth studio album was both his first to reach the top five on the sales charts as well as his first Platinum-seller since the 1970s. Its title is a nod to fans — those sun loving, clothing optional weirdos who sometimes get drunk and say silly things but who possess a positively essential joie de vivre. It almost goes without saying that most Parrotheads are not clothing optional weirdos. But it’s also worth saying that many of the teachers, lawyers and middle-managers that comprise his fanbase do fantasize about being carefree, clothes-free beach dwellers. And that is precisely Buffett’s appeal — how he taps into a primal need to escape. An urge to — every once in a while — exist in a liminal space between feeling warm and feeling nothing at all.

Pink Floyd “The Division Bell”

For as much as it was a David Gilmour album, “A Momentary Loss of Reason” was also a Roger Waters’ album. Every single review noted the absence of the band’s erstwhile leader, who was himself active and vocal in sharing his derision for the project. And while the record was commercially successful, it was doubly taxing. In its aftermath, Gilmore and Waters finally and painfully resolved most of their legal affairs but almost none of their enmity. For many years there was little hope, and no indication, of any future for Pink Floyd. But then, in 1993, the ink having barely dried on both his marital and professional divorces, Gilmour did something unexpected. He invited Nick Mason and Richard Wright—the latter of whom had been dismissed from the band during the making of “The Wall”—to get together, play some music and talk about the power of talking.

Asia “Phoenix”

If a computer—even a very old one—was tasked with naming an album made by the original four members of Asia who were reuniting for the first time in two decades, I am certain it would land on “Phoenix.” The metaphor of that ancient, immortal, mythological bird rising up again is simply too good to pass up on. “Phoenix” speaks to the passage of time, fire, beauty, erudition and regeneration. It is, in a single word, quite literally the perfect title for Asia’s comeback album—as ridiculous as it is accurate.

Ed Kowalczyk “The Flood and The Mercy”

Today, Live is Ed Kowalczyk plus paid studio and touring musicians. Ed’s childhood friends—Patrick and the two Chads—were relieved of their duties after years of lawsuits, countersuits and shady dealings with a shady con man. Meanwhile, Kowalczyk, now a fifty-something, rat-tail-less, father of four, charms fans on Totally Nineties tours and delights deejays on retro adult radio formats. But in between “Alive,” Ed’s confusingly named solo debut, and his return to Live, he put out another solo album—a commercial failure and a critical “nope.” Middle-aged me had zero interest in this record. But seventeen year old me—the me who was still a work in progress, who was so open to new things and who’d convinced himself that Live were cool and deep and important—felt otherwise.

Billy Joel “Turn the Lights Back On”

Billy had been stashing away ideas for years — parts of melodies, little hooks, half bridges, hummed choruses — but could not, would not complete a song. And so, rather than push him to the brink, Freddy Wexler politely requested to check out some of those song scraps. And eventually, through a combination of talent, elbow grease, Wayne Hector and Arthur Bacon, “Turn the Lights Back On” was born. The story is vague enough to be true. But it is also vague enough to make me ask, “Did Billy write the song at all?” The more I considered it, the more plausible it seemed that a very smart AI might have produced “Turn the Lights Back On.” Maybe Billy Joel’s new single was an AI deep fake. Maybe its perfection was actually an uncanny valley.

Los Lobos “Native Sons”

Over the course of nearly fifty years and seventeen studio albums, Los Lobos have been many things. A wedding band. A Rock band. A Folk band. A Punk band. They’re omnivores — multi-instrumentalists, songwriters, radical interpreters and loyal cover artists. Their influences are as diverse as their influence — members of the band have appeared on records from pretty much every legend who's passed through Los Angeles since 1980. From Bob Dylan to Eric Clapton and from Dolly Parton to Bonnie Raitt. Like their hometown, Los Lobos are diffuse. And like their hometown, they are Mexican. Which is why, more than anything, Los Lobos are underestimated. Pop music comes in many forms, but it gravitates to the specific and the English. Meanwhile, Los Lobos’ greatness lies in the fact that they are almost the complete opposite of those things.

Phish “Fuego”

I have a Phish problem. Or at least, for the last thirty years I’ve told myself that I have a Phish problem. This problem is in spite of my adoration for the state of Vermont. In spite of my having seen Phish perform live multiple times. In spite of being occasionally, but earnestly, wowed by the wizardry of their jams. In spite of my appreciation for their business acumen. In spite of my loving their Ben & Jerry’s flavor. Yes — in spite of all of it — I don’t abide. Which, for most people, would not be such a problem. But, as a Vermonter at heart, I am left with this unrelenting pull between my Yes-Vermont soul and my No-Phish conscience. It is a battle that, until recently, I had ignored. But it was a battle that I knew — someday, somehow — I’d need to resolve.

Rush “Vapor Trails”

By the time I reached middle age, my longstanding, polite refusal of Rush had settled into a wizened indifference. In fact, since I was not a subscriber to Guitar World or Drummerworld magazines, many years would go by without me hearing a peep about the band I’d once tagged “Loser Van Halen.” But then, one day, I caught wind of “Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage,” a documentary that was generating buzz on the festival circuit. That buzz swelled, culminating in awards, which begot a short theatrical run, which is where, in the summer of 2010, I was confronted with the most unfathomable of questions: What if the band I liked the least was the one I loved the most?

Night Ranger “Somewhere in California”

What happens to our dreams in middle age? Do they still matter? Were they silly to begin with? These are the questions we wrestle with on the other side of forty. And, as much as Night Ranger were an Eighties Rock band, they were also a middle-aged Rock band. Strictly speaking, they were more the latter than the former. While they released five albums during their heyday, they — amazingly — have put out eight albums since. Their most recent album, from 2021, was “A.T.B.O.,” an acronym for “And The Band Played On.” Its predecessor, from 2017, was entitled “Don’t Let Up.” The evidence suggested that Night Ranger wasn’t simply “hanging on.” That they were not content being “the Sister Christian guys.” That there was a destiny yet to be fulfilled.

Joe Cocker “Heart and Soul”

“Heart and Soul” was Cocker’s response to Johnny Cash and Rick Rubin — simple arrangements of classics, alongside unexpected takes on Modern Rock. Cocker, who had not flirted with contemporary material in decades, decided to cover (like Cash) U2’s “One” and R.E.M.’s “Everybody Hurts.” But unlike The Man in Black, who mostly talk-sang his way through the “American Series,” leveraging the bottom of his one octave range, Cocker pushed the upper limits of his instrument. He was like the aged athlete attempting to match the records of his youth. Like Carl Lewis trying to run a sub ten second 100 meter sprint today, at the age of sixty-two. Joe Cocker could obviously not sing in 2004 like he sang in 1969. But that was the humanity and the tragedy of this project. On occasion, it was touching and beautiful. Elsewhere, though, it was like watching a former Olympian tearing their achilles and then still gutting out the race, howling and limping their way to the finish.

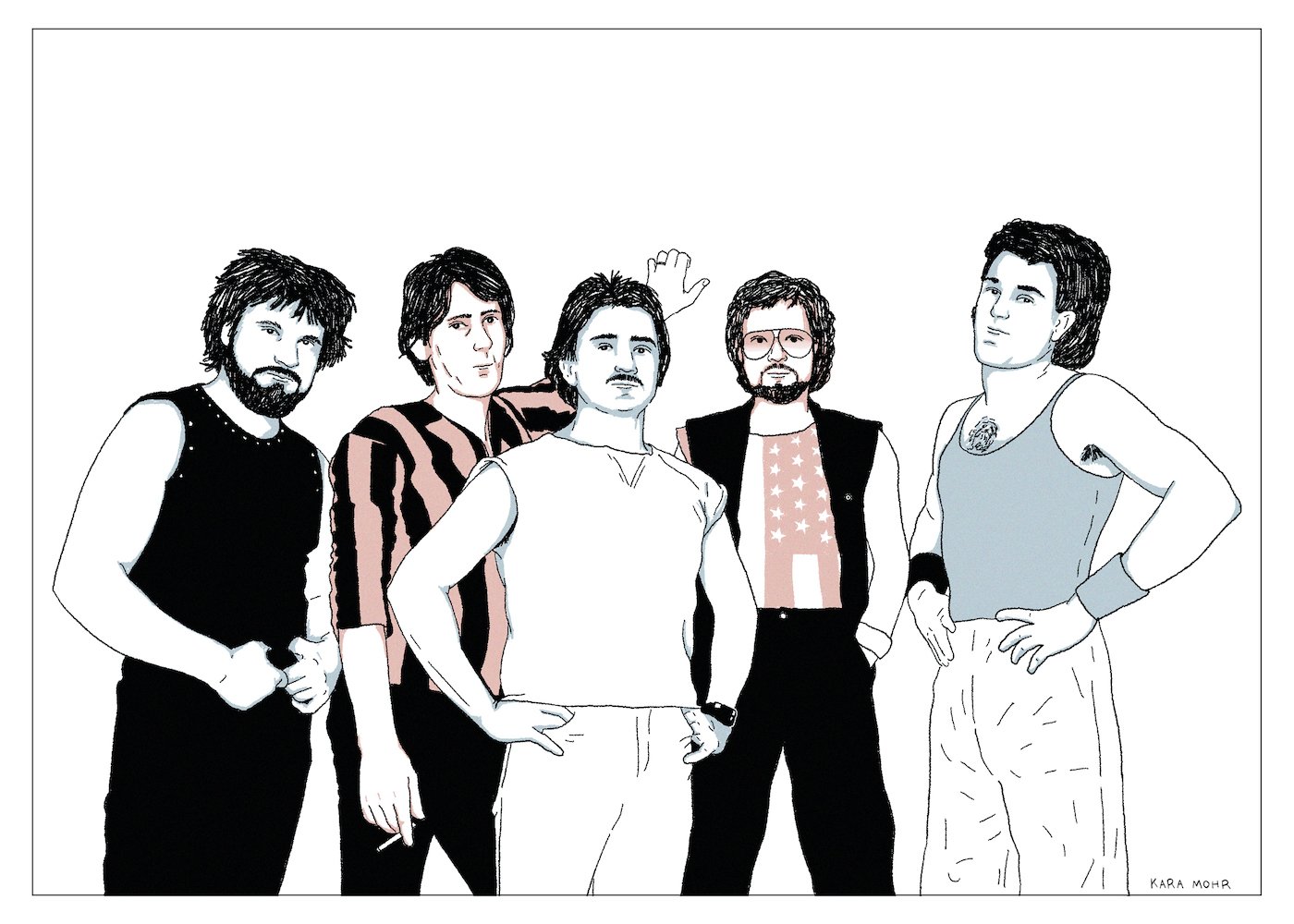

Loverboy “Unfinished Business”

Peak Loverboy is the sound of producer, Bruce Fairbairn, and engineer, Bob Rock. So is peak Bon Jovi. So is second peak Aerosmith and fourth peak AC/DC. It’s a big sound — heavy but not pummeling, bombastic but not ridiculous. It’s also a clean sound — every instrument has its place. It was their knob turning that made Bon Jovi sound like making out, Def Leppard sound like getting off and Loverboy like dry humping. As good as Loverboy was, their brief and unfathomable greatness was really that of their producer and engineer. A quarter century after their heyday, though, without Fairbairn or Rock, Calgary’s finest Arena Rock band returned one more time, as though to prove to Bon Jovi and Def Leppard who really came first.

Kansas “Somewhere to Elsewhere”

Three decades in, when “Dust in the Wind” was exactly that, Kansas was floundering mightily. Next to Styx and Journey, they almost made sense. But after Michael and Prince and GnR and Nirvana — Kansas seemed like the greatest accident in the Classic Rock canon. A legendary Arena Rock band that was actually a Prog Rock band and who were famous but also completely unknown. Many years removed from superstardom, they would never be cool again, but also, they were never cool to begin with. They would never have another smash hit, but they had two more than nearly every other band in the history of history. They dropped from a major label to a very niche indie who specialized in Prog and Metal, which meant smaller budgets but also a bigger slice of the pie. And so, by the dawn of the new millennium, Kansas existed somewhere between total liberation and complete decimation.