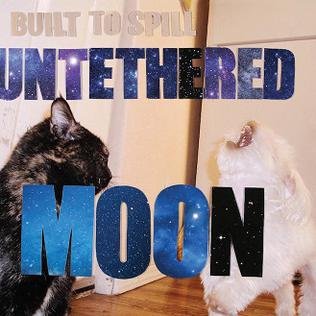

Built to Spill “Untethered Moon”

If I had to design an Indie Rocker — who knows why, maybe for a movie character or a book proposal, or whatever, because that’s not the point, but if I had to — I’d start with a guy. A guy from the Midwest or the Pacific Northwest, though not from a big city. He’d be above average height and lanky but in no way muscular. Maybe he played some baseball or basketball in high school. He might’ve been pretty good, but sports weren’t that important to him. He knows things. For example, he knows the answers in Physics and Chemistry class. Just like that — he knows them. He maybe smokes weed and drinks beer, but he never seems stoned or drunk. He’s introverted, but also has plenty of friends. He’s dreamy — not in the Jake Ryan from “Sixteen Candles” way, but in the always kind of thinking of something or someplace else way. He knows how to figure things out. He messes with the motherboard of computers. He’s confident with a toolbox. Also, he apparently has a band that nobody has ever heard but that you assume is pretty good. He plays guitar. In fact, he’s apparently great at it. And, though he’s only twenty-something years old, he looks like he could be forty. He’s even got the beard to prove it.

I’m not sure where this archetype came from — or if it is even archetypal. The description doesn’t fit the Indie Rock men of the 1980s. R.E.M. were too sensitive. The Replacements were too Punk. Sonic Youth looked like artists. None of those bands were bearded. Even Dinosaur Jr., who kind of fit the mold, were clean shaven during their first go round. Greg Norton from Hüsker Dü had a funny mustache — like Rollie Fingers, but that’s still not a beard. Meanwhile, Bob and Grant were fresh faced. In fact, it’s hard to find my bearded guy anywhere in the 1980s. There’s no old soul, College Rocker with a goatee. No Rick Rubin situation. Not even much in between. The Pixies don’t fit. Yo La Tengo don’t abide. Steven Malkmus with a beard? Imagine that. In most every measurable way, my archetype is more untrue than it is true. And yet, something about my guy feels correct.

By the mid-2000s, however, my avatars were everywhere. Justin Vernon. The Kings of Leon guys. Dan Auerbach. Jim James. Robin Pecknold. All bearded and fitting my imagined costume. By the new millennium, Indie Rock had metabolized Folk and Blues into its system. All of its stars wanted to look or sound more like Jerry Garcia or Harry Nilsson or “All Things Must Pass” George Harrison. For over a decade now, shaving has been out of vogue. Eventually, years after R.E.M. hung it up, even Michael Stipe returned as “my guy.” This new, furrier Indie Rock guy has been with us for quite some time. But where did it start? Who made the mold? Who was that guy? Had I misremembered? Was I conflating the beards of Grunge with the more collegiate Indie Rockers? Was my mind playing tricks on me?

No, I was not crazy. This guy was real. And though I needed to rack my brain more strenuously than I care to admit, I did eventually locate him. I had to go west past Chicago, all the way through Seattle and then south to Portland and then back east to Idaho. It was there, in 1992, that I found my guy. His name is Doug Martsch and he was most of those things that I described — and so much more. For about thirty years, Doug Martsch has been that guy and Built to Spill have been that band — dreamy, introverted, quiet on the outside but loud on the inside, occasionally bookish, frequently brilliant and generally bearded.

Built to Spill weren’t the first “Indie Rock Stars.” Depending on your definition, those came several years later with The White Stripes or Death Cab For Cutie or Modest Mouse. However, when they released “Perfect From Now On,” in 1997, on a major record label, and sold many tens of thousands of copies, they rewrote the book on their scene and genre. Before that year and that album, they were a hard to describe three piece from a small city that people had heard of but which very few could actually place. They released music on the appropriately indie, Up Records, and they played loud, warbly Rock with steady jangle and unsteady rhythms. They were less heavy and mathematical than what was coming out of Chicago. And less artful and pretentious than what New York and Boston had to offer. They were big, beautiful fish in a tiny pond.

Back then, Built to Spill looked grungey, but leaned closer to the tweeness of K Records than the angst of Pearl Jam. Like Eddie Vedder, however, Doug Martsch had great admiration for Neil Young and Crazy Horse. And like Neil Young (and unlike Eddie Vedder) Martsch had a reedy yearning to his voice. On guitar, he played like he was carving sculptures made of pixie dust through clouds of distortion. Nobody really played guitar like Doug Martsch, in part, because he sounded like he was actually multiple guitarists playing multiple guitars. But, also, because he was making rules up out of thin air. Slide guitar would meld into noise into crunching riffs into ecstatic jams. On “There’s Nothing Wrong with Love,” from 1994, we got a full dose of Martsch, and the duo that was equal or greater than its writer and frontman. Three years later, we got even more — in fact, much more than we could have ever imagined.

“Perfect From Now On” is one of Generation X’s last great Indie Rock albums. Four months after its release, Radiohead released “OK Computer” and everything about everything would be different. Obviously, my generation would fall in love with many other artists and records over the next couple of decades — The Strokes, Interpol, Bon Iver, LCD Soundsystem, Fleet Foxes, The Hold Steady. But none of those artists would be rooted in the same mythology as the bands that came before 1997. Twenty-first century bands were born on the Internet. They were twice removed from fanzines and years in tiny clubs and the wretched fear of “selling out.” Built to Spill were the younger siblings of the College Rock generation, born into the D.I.Y. religion. They were artful, but not pretentious, cynical but always dreaming of better, hard working but not careerist. They began in an era when the most successful Indie Rock bands sold ten or twenty thousand albums and worked two or three other jobs. They had seen Grunge and then Alternative Rock get co-opted in the blink of an eye. They’d predicted the through line from Nirvana to Foo Fighters to Nickelback. They just knew it would happen. And they were right.

Before the end of the twentieth century, however, Built to Spill were the exception to the rule. They were a three piece (not four) from the thirty ninth most populated state in the country. They sounded like they really liked Dinosaur Jr. and Classic Rock, but couldn’t effectively imitate either. Their music was kind of ugly beautiful, with a singer whose piercing tenor floated above a tuneful squalor. He sang words that could have been romantic poetry or surreal dreams or absolute nonsense. All of it seemed like magic, or a breakthrough of science. Plus…that guy. He’d lost most of his hair. And he had a grown man beard. He was not yet thirty but he might as well have been fifty. He seemed to have things figured out.

Among the many things that Doug Martsch and Built to Spill figured out was that “selling out” was a not super useful, probably self-sabotaging, construct. Though they were part of the fabric of Northwest Indie Rock, fraternizing with Calvin Johnson and Isaac Brock, Built to Spill signed to Warner Bros. Records in 1996. They retained complete creative freedom and enjoyed a commercial surge that allowed them to make a living wage through music. Their first two albums for Warner, “Perfect From Now On” and “Keep it Like a Secret,” are esteemed Indie canon. Both featured artwork by Tae Won Yu, the once de facto Creative Director for K Records. They both looked like Indie Rock records. They both sounded like Indie Rock records. They both were celebrated in fanzines. But, also, Spin and Rolling Stone and MTV2 paid attention. For about five years — between 1997 and 2002 — Doug Martsch got most of the things that J Mascis, Stephen Malkmus and the guys in Slint never dared to imagine. They got to have it both ways.

While those formative Built to Spill albums have endured, the “pre-Ok Computer” window of possibilities fully shut by 2001. It all started with the internet, which helped invent The Strokes. And then there was 9/11 and then there was simply no oxygen for Generation X’s previously independent ideals. Nothing was local anymore. I mean, fanzines and college radio and scenes still existed but they were also fully connected to a global culture and economy. Unpolished gems like Built to Spill with decade long careers were usurped by blog-gy bands that were beloved and then hated within eight weeks, or by artists with broader, more immediate commercial appeal. The middle class Indie Rocker was quickly outdone by the semi-Indie mogul or the Indie-ish millionaire.

In many ways, the democratization of popular music that threatened the larger music industry was actually a force of good for independent bands. Artists had more control over the apparatus of creation and promotion. Contracts were reimagined. Markets were opened. Whereas Built to Spill had once sold tens of thousands of albums, Spoon and The National would one day sell hundreds of thousands. There was something beautiful about the imperative of innovation. In most ways, it seemed like progress. Just not for Doug Martsch.

The end of Built to Spill’s iconic run came in July of 2001, with “Ancient Melodies of the Future,” released just three weeks before The Strokes “Is This It.” In most ways, their excellent fifth album resembled their previous work. Tae Won Yu cover. Phil Ek at the boards. Guitars on top of guitars. Melodically bright. There were also clear signs of evolution — a steadier rhythm section and more concise tunes. As had become custom, critics and fans adored it. But, if you listened closely, you could hear the march of progress beginning to grind to a halt.

After 2001, while Americans rallied around the flag and fled online and accepted the invitation to social media, Doug Martsch was creatively mired. In his significant defense, he had just completed a four album run that can be admirably compared to any stretch from almost any other Indie (using the term generically) band. Even today, “There’s Nothing Wrong with Love” through “Ancient Melodies of the Future” holds its own against the best four album runs from every semi-popular band not named “Pavement.” At some point thereafter, however, the wheels stopped spinning. The root cause of the malfunction is not entirely clear. It could have been exhaustion — Built to Spill were renowned road warriors. It could have been the unsustainable pace. It could have been some unknown internal tensions or the addition of a second guitarist or the absence of Phil Ek or writer’s block or the new generation of songwriters who were younger and prettier than, but equally bearded as, Doug Martsch.

Whatever the reasons, Built to Spill slowed down and — according to many — regressed. They released only three albums of new, studio material, after 2001. Some time in 2012, drummer Scott Plouf left the band to become a baker. Bassist Brett Nelson said goodbye around 2015. Martsch reconstituted the band several times, bringing his touring buddies into the studio and then shaking things up altogether. Meanwhile, his beard got thicker, those ringing melodies of his youth proved harder to recapture and his uncanny knack for words stalled out.

Eventually, he began to co-write lyrics with his wife, Karena. He openly confessed to struggling with new material in a way that he had not before. He sounded ambivalent, at best, with his words and their meaning. He suggested that listeners not read too much into his lyrics — that he barely knew what they meant. Simultaneously, he was mostly disinterested in mythologizing. He appreciated that fans loved his early albums. He even toured in support of anniversaries for “Perfect From Now On” and “Keep it Like a Secret.” But Martsch claimed he was unable to discern what made those albums great and more recent ones less so. By 2015, though he was “just” forty six years old, the face of Built to Spill looked as though it could have been sixty. Doug Martsch had always appeared older than his years. But, in middle age — bearded, grey and bald — he sounded like a man who’d skipped his second act.

At some point between 2010 and 2015, Built to Spill completed a recording session that yielded dozens of songs but no album. The six years since “There Is No Enemy” was their longest stretch between albums. For those that paid attention to this sort of thing, what started out feeling like casual patience grew into a more ominous sense of uncertainty. “Was Built to Spill done?” some fans wondered. It’s hard to imagine that Martsch, himself, did not at least occasionally consider the question. Though he’d always thought of Built to Spill as himself plus whichever friends would join him, he’d played with Plouf and Nelson for nearly two decades. Yes — his record sales and critical adoration had receded since the late 90s. But, moreover, it was starting to sound like Built to Spill might not have anything left to say. At least not as Built to Spill.

Fortunately, that was not the case. In April of 2015, Warner Bros. released “Untethered Moon.” In nearly every interview for the album, Martsch spends an inordinate amount of time explaining his anxiety with song lyrics. He’s never sure what to say. He’s never sure what his words mean. He throws out an idea and listens to what Karena writes and tries to make the words fit somehow. He’s content in his vagueness. He’s exhausted and nervous by the final mile of songwriting. In these interviews, when he’s not wringing his hands about his words, he’s professing indifference to musical trends. He’s enamored of decidedly loud, ragged and retro acts like The Oh Sees and Ty Segall and King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard. As for everything else that happened after 2001, he sounds only vaguely curious.

Like many of us in middle age, Doug Martsch had figured out the style that most suited him and decided to stick with it. For Built to Spill, it was layers of guitar and feedback, bass, drum, jamming when appropriate and whatever words the singer could dream up. However, his conservative, almost regressive, posture was in conflict with the songwriter whose musical searching and vocal yearning had once been progressive, to the point of magical. While Bon Iver flirted with Hip Hop and The Strokes cleaned up their act and James Murphy professed “I Can Change,” Doug Martsch opted to mostly stay the same, save for his beard, which got grayer and fuller.

When it did finally arrive, “Untethered Moon” was described as a “return to form” by more than one critic. After all, it was recorded as a three piece, whereas the previous two BTS albums were not. Additionally, it was produced by Sam Coomes, of Quasi, Up Records and Pacific Northwest utility guy fame. There were apparently a couple of monster jams and more guitar sorcery than the most recent albums. Though not explicitly stated in the media’s framing, it was suggested that Built to Spill was in need of a return to form. Perhaps not that Martsch intended it or wanted it, but rather that we — as fans — did.

While there were still many loyalists rooting for Built to Spill, there were as many — if not more — who’d given them up years earlier. I counted myself in this latter group. I’d never specifically turned on the band. I’d simply stopped waiting and occupied myself elsewhere. As a result, other than possibly hearing the album’s single, “Living Zoo,” on the local, public station here in Austin, I had no idea what to expect from Doug Martsch twenty plus years after “There’s Nothing Wrong With Love.” I’d probably read reviews about “There Is No Enemy,” and suspect I’d pressed play on Spotify. But those were probably the only non-nostalgic encounters I could claim. I’d simply not kept up. Fortunately, for me, I’d not lost touch — Doug Martsch had not gone very far.

“Untethered Moon” opens with “All My Songs,” which, in its gear-shifting propulsion, layers of guitar and off kilter tunings, is true to its title. Most everything about it is familiar, but also not quite right. Doug’s voice is more hushed and mixed middle. His yearning never cuts through the guitars. And the pops of melody are scant amid a series of semi-related guitar ideas stitched together. Though the tones are relatable, it lacks both cogency and — despite its relative girth — the sweep of an epic. For a song that was clearly labored over for many years, it feels tentative. In fact, maybe that’s the point. Martsch repeats the refrain “I’m sure that I’ll be alright / But I don’t know” in a manner that echoes the music’s uncertainty.

Built to Spill’s eighth album is mostly a throwback, which likely comforted fans who’d resisted the minimalism of their previous two albums. If Sam Coomes had hoped to recapture the manner of Built to Spill’s second, third and fourth albums, he generally succeeded. The chords have the warble of 90s Indie Rock and the guitars, pedals and effects are piled high, surrounded by clouds of feedback. Much of the band’s alchemy was rooted in the tension between Martsch’s unpredictable, often breathtaking guitar work and the band’s faster then slower, and then faster again bass and drums. Those hairpin turns, girdered by sunny melodies and a pining lead singer, are as evident in 2015 as they were in 1995. Unfortunately, they are only present in short bursts or in attenuated forms.

“Living Zoo,” the album’s ostensible single, is as close as we get to “Keep It Like a Secret.” The guitars roll and chime over a skittish bottom. Aside from a couple incendiary leads, it is the most concise and assured track on the album. On the other hand, it is also a deeply cynical, possibly terrifying, song that speaks to our lack of agency, our lack of meaning and our lack of humanity. There is a deeper, more abstract truth about it that feels a long way from the more sensitive and personal, not yet thirty something who wrote “Carry the Zero.”

The best hooks on “Untethered Moon” are of the jangly, acoustic variety. “On the Way” and “Never Be The Same” both eschew volume and noise in favor of simpler pleasures. In their modesty, there’s a maturity that befits Martsch’s middle age. He’s still trying. He’s still wondering. But there seems to be less desperation in his search. To some, the lower stakes may feel like a let down. I admit to occasionally wishing we could have frozen Built to Spill in ember in 1999. But, that desire is profoundly unfair, and kind of grotesque. Doug Martsch has more than earned some settling down. Unexpectedly, the more casual “Untethered Moon” gets, the happier I become for the singer-songwriter.

Though not quite so easygoing, “Some Other Song” still succeeds. The hook is heavier and at an odd angle, like something June of 44 or Don Caballero would have played twenty years earlier. The beat, on the other hand, is unusually consistent -- no wild fills or detours. The dense tone, however, is effectively betrayed by the vulnerability of the lyrics:

I don't know how to never fall apart

Please tell me how to never fall apart

No matter how you ever fall

Two songs later, on “C.R.E.B.",” the band takes their protractors out again and attempts to combine Math Rock with Dub — a genre that Martsch was more than a little enamored of. To further complicate matters, the song at least nominally deals with neuropsychology. Ultimately, the unlikely pairing proves unsavory. It’s a lot to work through and probably not a great fit for Martsch’s voice. However, on an album typified by the casual and familiar, this odd experiment — even in failure — sounds spirited.

Built to Spill saved the wildest swing for the end. “When I’m Blind” is eight minutes of bleating guitar and noise. For most of its duration, the drummer stays remarkably, almost maddeningly still, while the guitarist freaks out. Martsch plays the first half with a leaden hand, the way Neil Young sometimes plays with Crazy Horse or how Bob Quine played with Lou Reed. It sounds not unlike Eddie Van Halen’s “Eruption,” but after the lava has begun to dry. While not exactly pleasant, you stick with it because you feel something building. However, around minute five, when everything starts to fall apart, you wonder if what you are listening to is a song or a jam or just entropy. The hook that it opened with gets buried deeper. And deeper. Until there is no hook. But, eventually — graciously — they find their way out of the darkness. In the home stretch, the drums and bass are revived and the guitar revs its engine. The last minute is a dead sprint — a drag race. It’s bracing — as good as the very best moments from any Built to Spill song. And probably worth the wait. If this were the last minute of music we ever got from Built to Spill (which I hope is not the case), it would be somehow fitting.

Over the years, and in spite of his possible ambivalence, Martsch has earned a tremendous amount of good will. When you’re from Boise (suddenly the most interesting city in America) and play guitar like no one else and tour relentlessly and make three or four beloved albums that stand the test of time, people tend to listen with a generous ear. “Untethered Moon,” which received its fair share of four star reviews, certainly benefited from that kindness. As somebody who once really loved the band and then who lost touch for many years, it can be hard to assess how much of my own affection is wistfulness and how much of my criticism is an unfair standard.

Nearly twenty five years since they blew up my mind in Olympia, Washington at Yoyo A Gogo, Built to Spill is not a band that really concerns me. Naturally, I am more preoccupied with my own second half than with that of my musical heroes. That’s normal. But, also, it’s been over six years since “Untethered Moon” and much longer since I’ve seen them perform live. In many ways, my disinterest feels hard to justify. But, in one specific way, it is simple: Built to Spill made it. Of their generation of Indie Rockers, they were one of the very few who made it through to the other side. Doug Martsch will be fine. He doesn’t need my worry. He’ll always be the kind of tall guy with the beard from someplace that’s not New York or Chicago or L.A. or San Francisco that sounds like Neil Young and Crazy Horse, as performed by the K Records house band. To me, he’ll always be the face of Indie Rock. He can do whatever he wants. Or nothing at all. Heroically, tragically, he will always be an archetype.