The Clean “Mister Pop”

In the second half of their third act, The Clean seemed increasingly disinterested in both their legacy and their future. Their first three albums—“Vehicle,” “Modern Rock” and “Unknown Country”—did not suffer from from this malaise. But “Getaway,” their fourth, was a minor backslide. And then came “Mister Pop,” their fifth and (now) final release, which sounded less like an album and more like a collection of lightly polished demos. For many years “Mister Pop” felt like a footnote in the band’s tiny but seismic discography. However, by 2023, after the death of Hamish Kilgour, it felt like a swan song.

The Black Heart Procession “Six”

If Hot Snakes embodied the face of post-Hardcore San Diego—molten & unrelenting—Black Heart were the underside—dusky & longing. Pall Jenkins & Tobias Nathaniel made aching nocturnes—hardly Rock songs—better suited for Victorian lockets than iPods or CDs. But after five albums of unopened letters about unrequited loves, “Six” made the turn from noirish black to Hot Topic black. You could read it in the track listing—titles like “Drugs,” “Heaven & Hell” & “Suicide”—and you could see it in the cover design—pagan crosses & “SIX SIX SIX” scrawl. All signs indicated that the carnage was more B-movie horror than emotional distress—that the aesthetic feature had become a shticky bug.

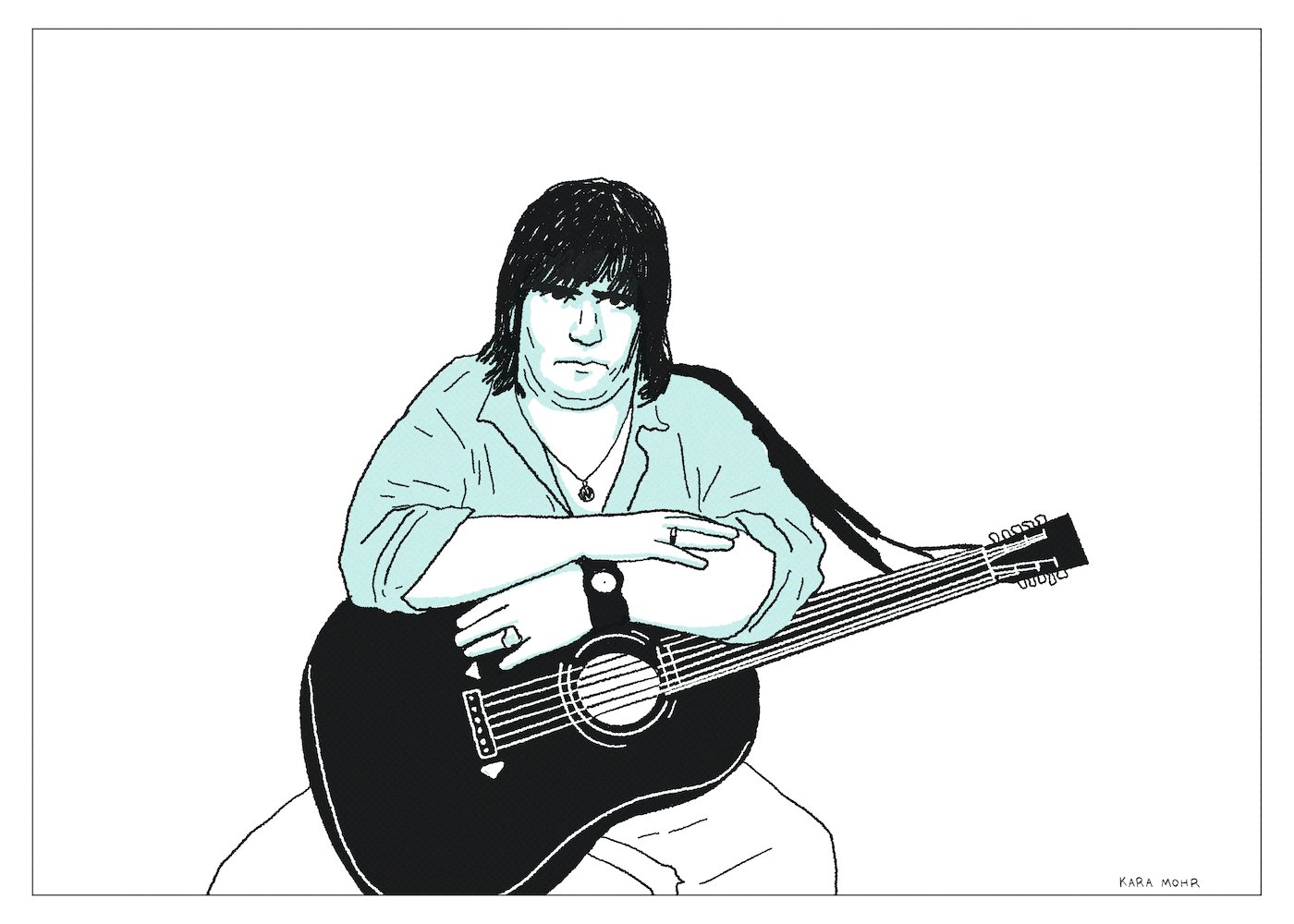

Magnolia Electric Co. “Josephine”

By the time of “Josephine’s” release, Jason Molina was almost completely out of the picture. Those who were still following along understood that while Molina might always be the patron saint of Secretly Canadian Records, Justin Vernon was the prodigal son of the Secretly Canadian Empire. And that while Jason Isbell might have looked upon Molina with reverence, Americana’s new “It Boy” had bested his predecessor in the popularity contest. In 2009 Molina was neither as new as Vernon nor as sociable as Isbell. Meanwhile, reviews of “Josephine” were ambivalent and sales were middling. In the end, Molina’s return proved to be shaky and short lived. Soon after “Josephine” arrived, he cancelled tour plans for “health issues.” And over the next three years, aside from the occasional rumor or warning flare, Jason Molina was basically a living ghost.

The Olivia Tremor Control “Garden of Light” and “The Same Place”

Whereas Bill Doss was a hard working free spirit, Will Cullen Hart was more of a boundless tinkerer. Doss’ songs have an easy air about them — they feel well-crafted but also kind of effortless. Hart’s songs, on the other hand, sound unlike anything or anyone else. If The Olivia Tremor Control were a miracle, Hart was the miracle worker. And of the many miracles he performed, none were more miraculous than the ones he manifested on November 29, 2024. That day, at the age of fifty-three, he bequeathed us “Garden of Light” and “The Same Place.” The surprise of these two gifts — the first new music from OTC in fifteen years — was all the more mind boggling, though, when you consider what immediately preceded them. Just a few hours earlier, Will Cullen Hart had passed away from natural causes.

Bon Iver “Sable”

As Bon Iver evolved from loner in the shack to experimental Jam band, Justin Vernon became more diffuse — and more opaque. His voice was everywhere, but his songs were impossible to decipher. His career was simultaneously safe and unpredictable. He was Indie Rock canon verging on Pop canon, but one never knew when or if the next album would come. And one never knew what it might sound like — except that it wouldn’t sound like “For Emma, Forever Ago.” Justin Vernon was not going back.

Joey Ramone “Don’t Worry About Me”

“Don’t Worry About Me” is almost exactly what you'd expect from a Joey Ramone on death's doorstep solo album. Which is to say it’s alternately frightened, bored, unfinished, funny, maudlin and brilliant. Joey croons, bleats and tawks his way through eleven tracks, all (but one) of which clock in under four minutes, but none of which are under two. The (by Ramones’ standards) mid-tempo nature of “Dont Worry About Me” — the seeming lack of rush — suggests a pace afforded by age, poor health and, most of all, no Johnny Ramone. Johnny had zero time for bullshit. But, especially at the very end, Joey had all the time in the world for it.

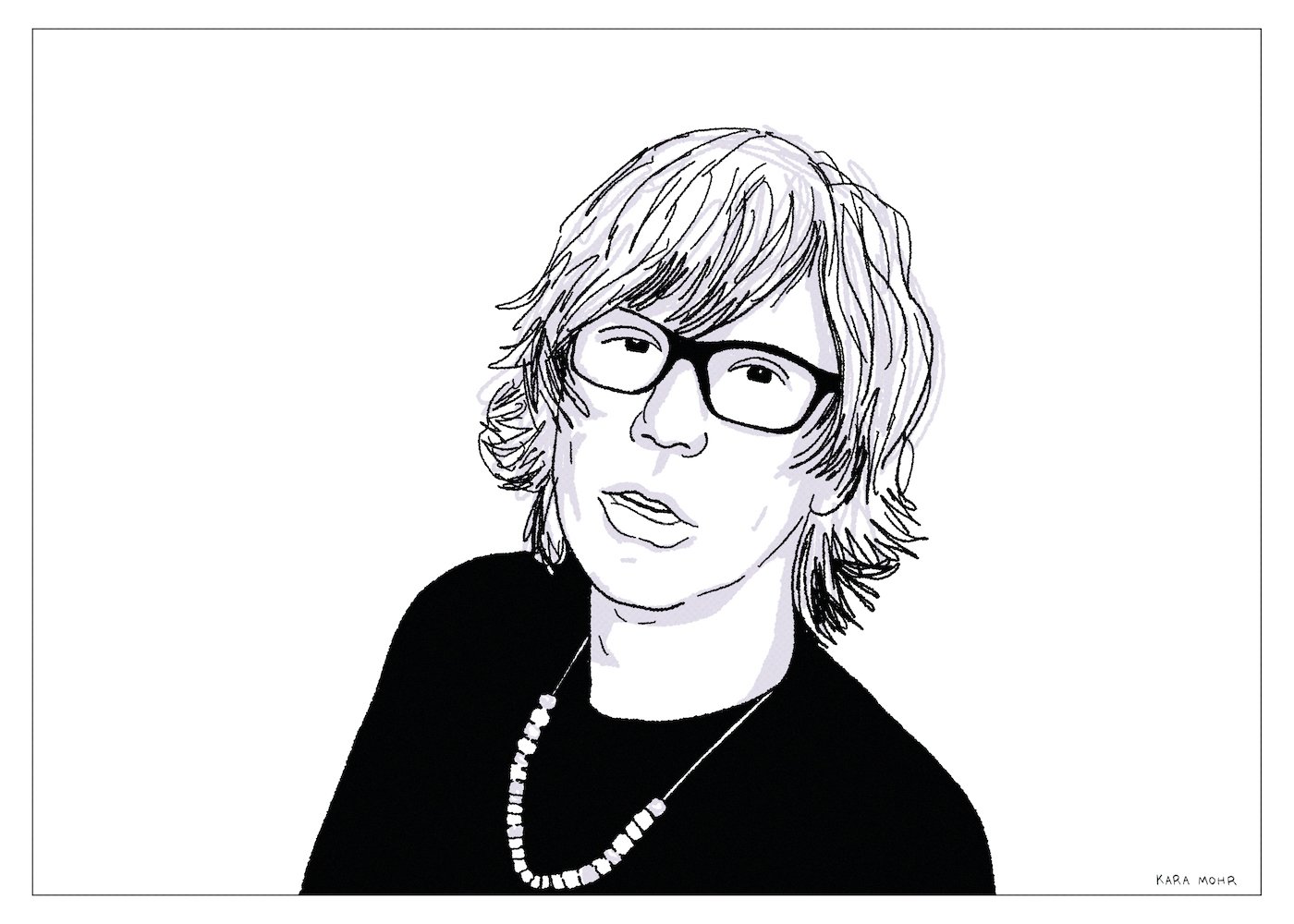

Sebadoh “Defend Yourself”

If Lou Reed was the first and the alpha, then Lou Barlow was the distant second and the beta Lo-Fi Lou. With Sebadoh, Barlow invented the kind of work in progress, kind of perfect as it is style that Guided by Voices and Olivia Tremor Control soon perfected. With Sentridoh, he invented an even quieter, decidedly unpunk alter ego that Iron & Wine and The Microphones cribbed notes from. And before all that, of course, was Dinosaur Jr., where Barlow’s Cardigan Cat Guy guise debuted. Yes — before Kurt Unplugged, before Elliott at The Oscars, and way before Taylor’s Tortured Poets Department — Lou Barlow was whispering the way.

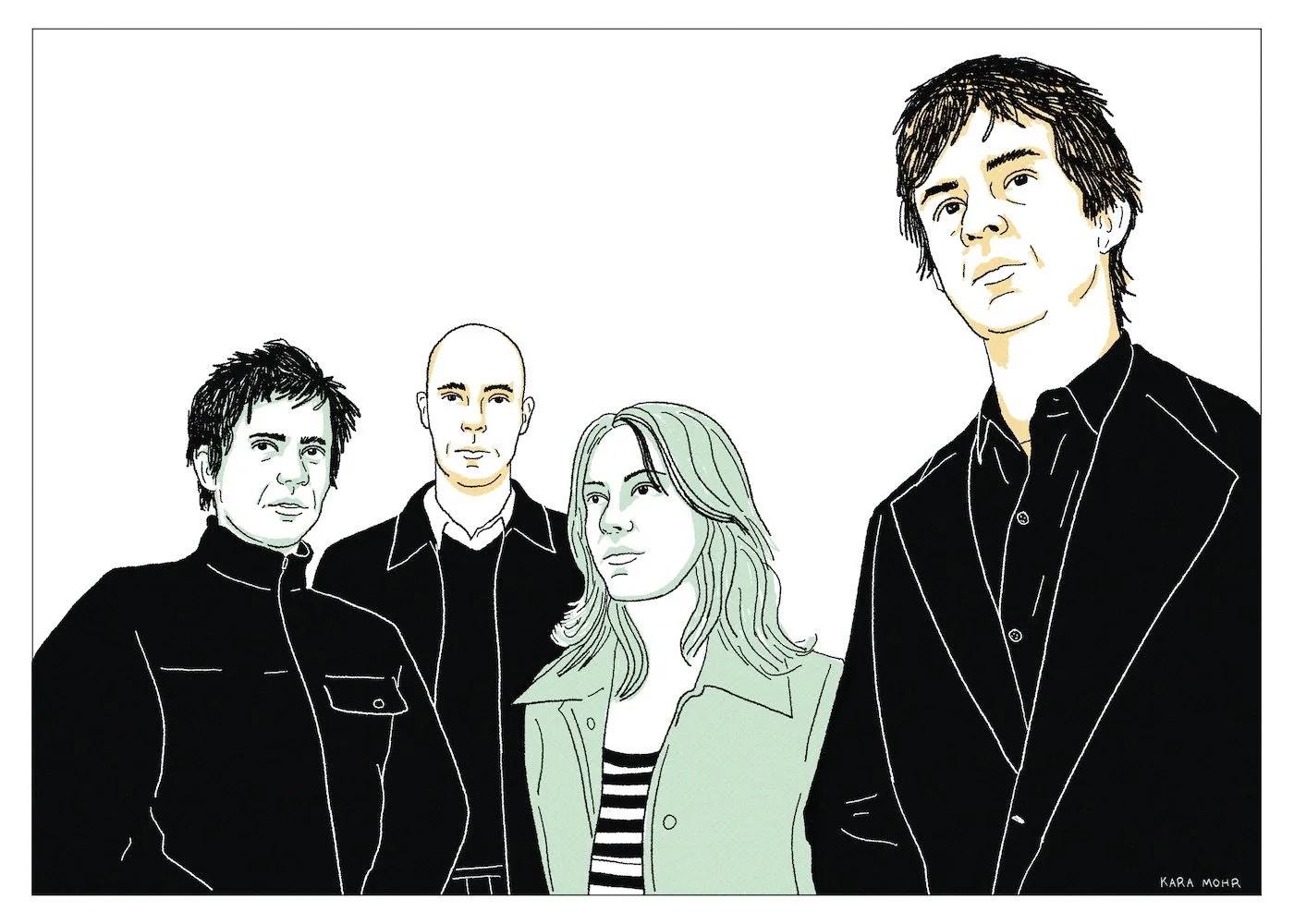

The Baseball Project “Volume 1: Frozen Ropes and Dying Quails”

While they aren’t Hall of Famers, Steve Wynn and Scott McCaughey are the subjects of indie fascination and the stars of The Baseball Project. On “Frozen Ropes and Dying Quails,” Wynn has seven writing credits to McCaughey’s six. Meanwhile, the actual Hall of Famer—Peter Buck —operates as a role player and drummer Linda Pitmon calls the pitches from behind the plate. In The Baseball Project, the frontmen are actually journeymen. Which, I think, is a big reason why the band works—because they are a team. Everyone is working in service of the same goal. And it’s a very specific goal—to make always witty, occasionally poignant songs about baseball’s great history. They’re not aiming for hits, much less home runs—they just want to play ball.

Luna “Rendezvous”

Just a decade earlier with Galaxie 500, Dean Wareham realized something profound and profoundly obvious—it’s hard to be in a band with a couple. Back then, he was the frontman who was also the third wheel. But in 2004, with Luna, he was the frontman and one half of the couple. Which is why “Rendezvous,” Luna’s seventh studio album, was meant to be their last album. Recorded during their farewell tour, “Tell Me Do You Miss Me,” is a feature length documentary about life on the road for a well known, well loved, but ultimately not known or loved enough indie band. There’s a lot of pleasure. And there’s even more pain. On the surface, it’s the story of a band breaking up because they just can’t make a living. But you didn’t have to scratch too hard to uncover the other truth—the story of a band breaking up because their lead singer and bassist had fallen in love.

Steve Earle “I Feel Alright”

In 1996, having shaken off five years of rust, sixty days in jail and a couple decades of addiction, Steve Earle released “I Feel Alright.” Whereas 1995s “Train a Comin’” found him looking backwards, “I Feel Alright” was a completely present album. It was vintage Earle, after the pink cloud had dissipated—honest, aching, and feeling “alright.” Which is to say he was not feeling great. But also he was not feeling awful. It was a hedge—somewhere between cautious and optimistic. “I Feel Alright” is the ultimate one day at a time response to the question, “How you doing?” As a description of Earle’s state of mind, it sounds appropriate. As a title for his sixth studio album, it feels like a radical understatement.

Boeckner “Boeckner!”

At just eight songs and barely thirty minutes, “Boeckner!” is closer to EP than LP. And if judged as an EP — the format which Wolf Parade chose to thrice introduce themselves way back when — I’d call it a success. A couple misses, a couple stash aways and four songs that justify the titular exclamation point. But considered as an LP, “Boeckner!” does feel a bit small. Or rather a little short. Which sends me back to Joe Strummer — Boeckner’s spiritual forebear and the most important guy in the most important band in the world who never had the will or the want or the whatever to be that guy outside of The Clash. As magnetically cool and as evidently smart and talented as he might be, Boeckner — like Strummer, like most of us — needs a partner. Twenty years with Spender Krug. A glorious season with Britt Daniel. Five plus years with Alexei Perry. And, for nearly decade with Devojka, Boeckner’s bandmate in Operators and co-writer on half of “Boeckner!”

Pitchfork “0.0”

It’s been a couple of weeks since Condé Nast’s decision to reorganize and downsize Pitchfork, a move that drew head scratching disbelief and foot stomping ire from everyone with an opinion on the matter. As with all corporate shake-ups, the full implications won’t be understood for some time. But what is knowable now, and for certain, is that (a) many people lost their jobs and (b) Pitchfork was one of the first Condé Nast titles to successfully unionize and (c) the writing at Pitchfork was never better than it had been recently, under Editor & Chief, Puja Patel. Meanwhile, what should have been known to Anna Wintour (Condé Nast Chief Content Officer), Roger Lynch (Condé Nast CEO) and Nick Hotchkin (Condé Nast CFO), is that nobody under the age of fifty gives a shit about G.Q. (the title that Pitchfork was reorganized into) and that many people give many shits about Pitchfork.

Bry Webb “Run With Me”

Some bands are corporations, like The Rolling Stones. Some are communes, like Big Thief. Some are gangs, like The Clash. The Constantines, however, were more like a union — the genuine article. They were brothers in arms, in jeans and flannel. But when their mission inevitably bumped up against the realities of family and finance, the union dissolved. The miracle was not that The Cons broke up. The miracle was that they were so true and so committed for as long as they were. Just four albums. Not even a decade. But they never stopped waving the flag. Never stopped working. Which is why Bry Webb needed a break. Why, first, he left for Montreal. And then to Guelph, outside Toronto, where he started anew — as a husband, a college radio programmer and the maker of quiet, plaintive songs about the glow and glare of new fatherhood.

Kevin Drew “Aging”

Since “You Forgot It in People” — the record that a generation made out to and broke up to — every Broken Social Scene album has been an event. The reveal of who’s in and who’s out and the inevitable comparisons to their masterpiece. But while they have all been events, they have been more so celebrations. For all of the gothic romance of “Lover’s Spit,” Kevin Drew sure seems like a jubilant fellow. “Hug of Thunder” is his brand. He’s the glue and the vibes. But he’s also a guy who exists outside of his collective. In between those BSS records, Drew has been releasing lower stakes solo albums. Initially, with many members of Broken Social Scene. Then with a few. And then, finally, all alone.

The American Analog Set “For Forever”

Though they broke up in 2008, The American Analog Set started hanging out again in 2013. They’d meet up weekly and play music for the purest of reasons — because they enjoyed being together. It was familiar and comfortable. But in no way did their weekly jams sound like a reunion or even a precursor to a reunion. On the other hand, it did beg the question: If a band plays in a living room for no one but themselves, are they even a band? If a tree falls in a forest, does it make a sound? In truth, nobody knew about these private get togethers and so nobody was asking. But then, a year or so ago, the fading flicker made a pop. Numero Group announced plans to reissue the first three Analog Set albums. A lost track came to light. And then, seemingly out of nowhere, The American Analog Set, who were always as much a dream and a mystery as they were a band, revealed “For Forever,” their first album in eighteen years.

The Hold Steady “Thrashing Thru the Passion”

Of course we loved them. How could we not? After The Strokes and Interpol we needed something seriously less serious. We asked, and Saint Paul answered with The Hold Steady, a bar band that was also a bard band. Five guys who liked to drink and who sounded like Thin Lizzy covering The E. Street Band covering “Tangled Up in Blue,” but with Randy Newman on vocals. Three albums in, they represented everything that was great about Brooklyn. Three albums later, they seemed more like the downside of gentrification. Album number seven, however, which was released five years after their disappointing sixth, was a triumph — a recollection of where they had come from as well as an honest assessment of the price of progress.

No. 2 “First Love”

Soon after the breakup of Heatmiser, Elliott Smith was an internationally renowned, critically adored singer-songwriter. But less than five years after his breakthrough — after he stood nervously on stage in a white suit, singing “Miss Misery” for some of the most famous people in the world — Elliott Smith was dead. By that point, his former bandmate and college buddy, Neil Gust, had moved from Portland to New York City, where he gave up his rock and roll ghosts and let the bruises of Heatmiser fade. Gust traded in his band for a three person domestic partnership, and traded in his guitar for a video editing suite. The man who was once Elliott Smith’s closest friend and who was, for a time, also considered his songwriting equal, became a successful commercial video editor. But nearly twenty years after his last record, when he was fifty years old, Neil Gust returned to Portland and started making new music again.

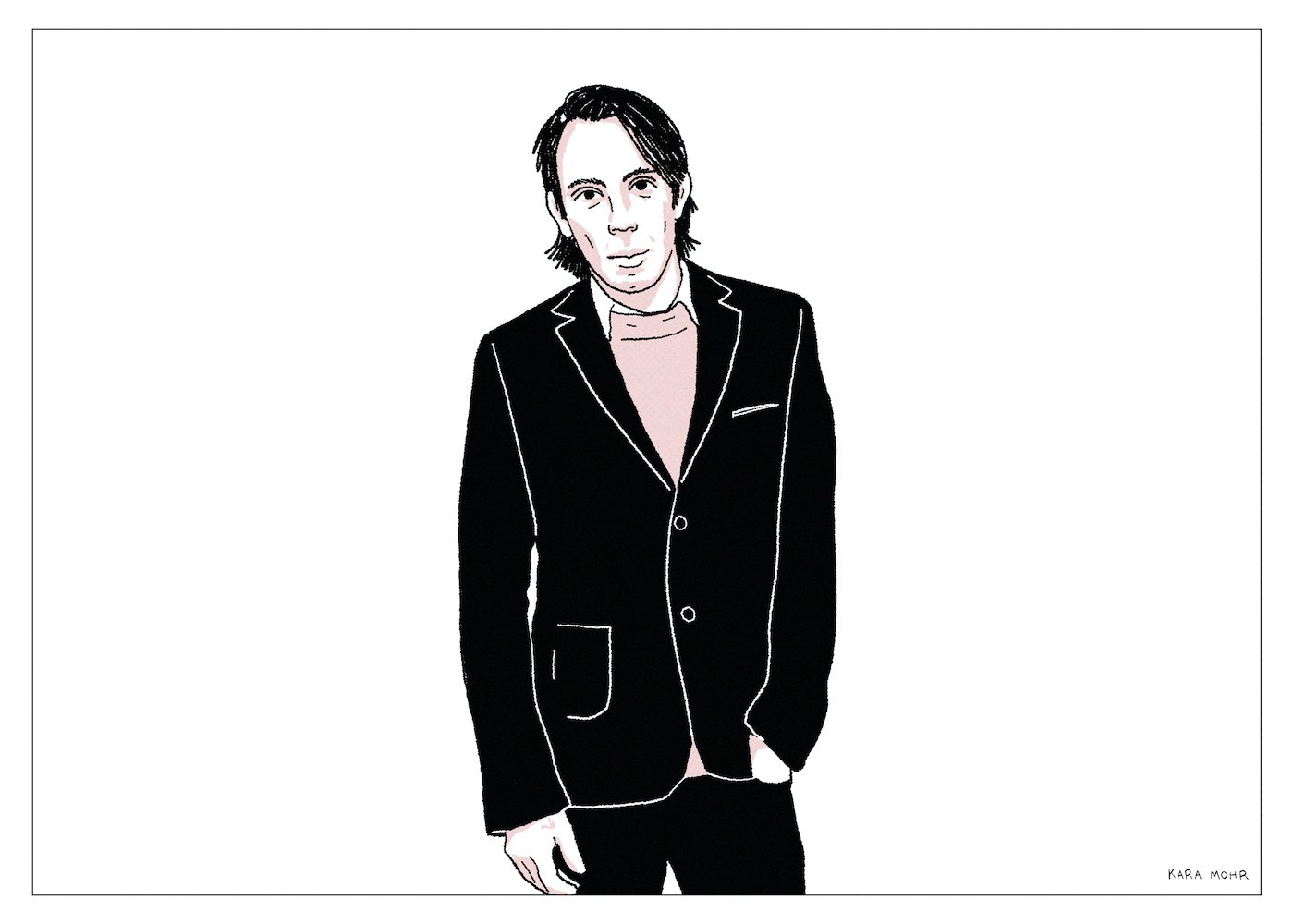

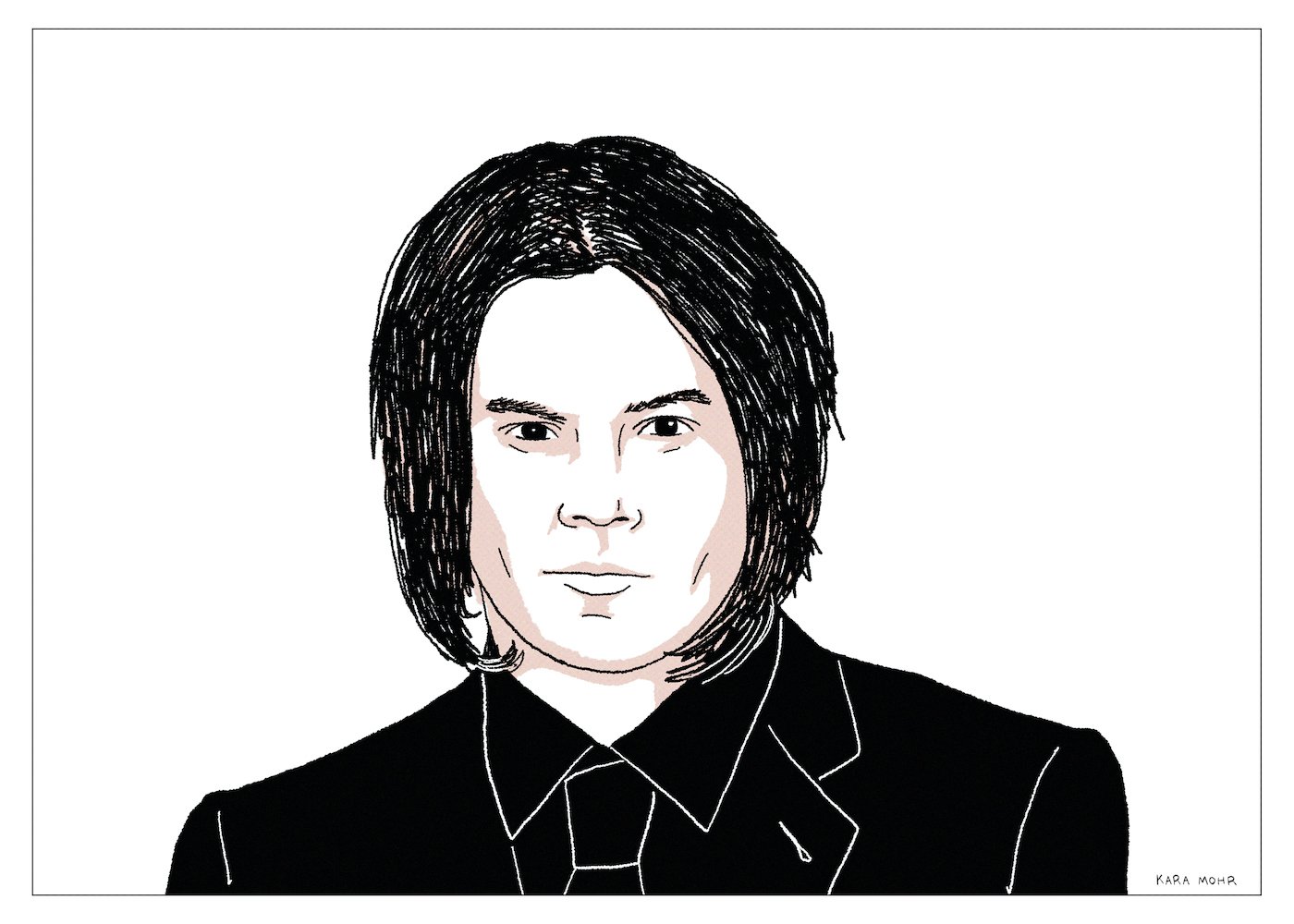

Destroyer “Have We Met”

Destroyer’s ninth studio album, “Kaputt,” was the rare album that succeeded poolside at boutique hotels as much as it did inside Urban Outfitters as much as it did at grad school cocktail parties. In the career of Dan Bejar, and in spite of everything he had accomplished before — with Destroyer and with The New Pornograohers — there was “before Kaputt” and “after Kaputt.” After “Kaputt,” a lot changed. Bejar got semi-famous. His clothes got fancier. His hair got bigger — and slightly grayer. Strangers wanted to talk to him. People wanted to hear what he had to say. And, moreover, what he meant. Was he really a master making masterpieces or was it all just artfully arranged, magnetic poetry from the most interesting man in North America?

Jack White “Entering Heaven Alive”

Willy Wonka succeeded because he was more fun than he was weird — which is saying a lot because he’s really fucking weird. But the older Jack White got, the less we could detect the humor in his Wonka-ness. Where there was once “Sugar Never Tasted So Good” and “We’re Gonna Be Friends” there was now dystopian Nashville, Steampunk Blues and Art with a capital “A.” To be clear, I have absolutely nothing against any one of those things. But stripped of its wide-eyed delight, White’s music began to veer from strangely astounding into the realm of astoundingly strange.

Thurston Moore “Demolished Thoughts”

More than any American Indie band from the Eighties, it is Sonic Youth who cast the brightest light and deepest shadow. Kim, Thurston, Lee and Steve broke rules and made albums of consequence. They were anti-establishment, even when they became the establishment. And they were groundbreakers in spite of their traditionalism — four pieces, two guitarists, one bassist, one drummer. But, as much as for their music, Sonic Youth was important because of Thurston and Kim — how they looked, how they acted and, most of all, what they signified about marriage and partnership. For every person who’d actually listened to “Daydream Nation” or “Sister,” there were dozens more who knew about Kim and Thurston. And every one of them knew intuitively — and with great certainty — that they were a marital ideal. Until they weren’t.