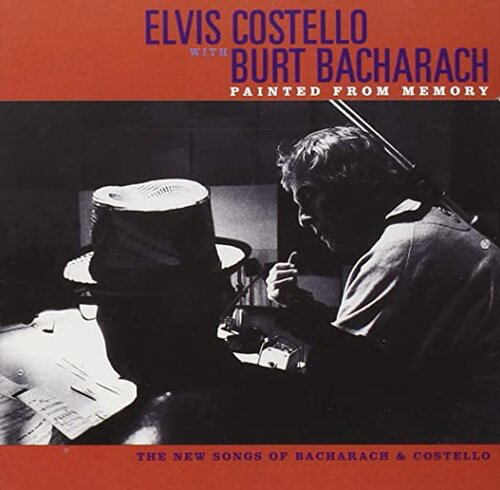

Elvis Costello “Painted from Memory”

This project started from a track commissioned for the Allison Anders film “Grace of my Heart”, a fictional biopic of a Carole King-type, Brill building era songwriter trying to break out on her own. Costello and Bacharach collaborated on “God Give me Strength” for the film, a real showcase for Costello’s voice and Bacharach’s delicate restraint. The new songwriting partners decided to keep going. “Painted from Memory” was an assertion of Costello’s identity as a music lover unattached to genre. It wasn’t his first dip out of Rock n’ Roll. He had a historian’s ear for music. He made his mark as a punk, but that may have just timing. He shifted around, doing a Soul and R&B inspired album, an unpopular Country album, a run at Beatles inspired pop, a chamber album with the Brodsky quartet, and a critically acclaimed Americana tribute. But none of these were quite as courageously easy listening as “Painted from Memory”. The tracks are, for the most part, piano based torch songs with Bacharach’s smooth horn arrangements — tasteful jazz-leaning pop confections. The two songwriters share a flair for writing unusual syncopated melodies, and their own idiosyncratic phrasing. Costello seems happy to slip into a more AM radio mode, lounge singing at the airport so you can ease in and do some duty-free shopping. If you lift your ear up from your deep discounts at the store, you’ll find a clever solution to the mid-career conundrum.

Elvis was indeed clever. It was a strength and an impediment. He was a nerd’s hero — a smarty-pants who somehow became cool despite the glasses. But intelligence can become a block from emotional connection when an angry punk turns 40. Seething is a young man’s game. Costello was reaching down into the tradition of popular song for fuel. Bacharach and his lyricist Hal David came from the era when it was more of a job and less of a revolution. Bacharach served as Marlene Dietrich’s composer and accompanist, wrote 15 hits for Dionne Warwick, then tackled the movies with hits like “Alfie” and “Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head”. Elvis was actually only nerd cool. He was a secret music librarian and idolized the work and work ethic Bacharach, like film directors who fantasize about working for the old studio system, grinding out hits for Louis B. Mayer. Costello had street cred more than hits. Bacharach had hits more than street cred. They both needed each other. “Painted from Memory” is a slip, an impressive pump fake from where you thought the rocker was headed. What’s most impressive, though, is how completely Costello gave himself over to his collaborator’s style. This is far afield from Costello’s native environment, but they fuse into something greater than the sum of their parts.

The second track on “Painted from Memory,” “Toledo,” lives in a Herb Albert and the Tijuana brass universe. But Elvis’ fresh vocal reminds you of how narrow that description is. The music hides its complexity in inverse to the roguish manner Elvis wore on his sleeve. “Toledo’s” time signatures are as deft as any prog-rock creation, but they flow organically and conceal their difficulty under Bacharach’s light touch. The lyrics of “Toledo” are about the character’s hesitance at revealing an affair, and a whimsical escape to a fantasy outside himself.

But do people living in Toledo

Know that their name doesn't travel very well

And does anybody in Ohio dream of that Spanish Citadel

The slip into fantasy is scored with a lilting upwards that carries you over the ocean. The verses grapple with the guilt, and the return to the chorus tries in vain to take the author to a place between Spain and Ohio where actions have no consequences. It’s an impressive creation, fully investing you in a playboy’s romanticism without dodging his sins. Costello had experience as a cad, but this is not a trick Elvis was able to do alone. On his own, he was better at skewering himself or chronicling his retorts. Bacharach lent a whole different palette of music that opened up a new spectrum of emotion. It’s a much more sophisticated con, like having the victim swoon and thank you for taking her purse.

Costello unchecked, defaulted to writing from a sulk — a smart sulk — but griping so intelligently at the short end of the stick, that he flips the situation to his advantage. On each track of “Painted from Memory”, Costello trades his acerbic wordplay for direct narrative of unraveled relationships. That may have been the shared ground they could work from. Both singers had their share of relationship ruin — four divorces between them. Bacharach’s influence encourages Costello to keep his head out of the equation and be a simpler storyteller. Costello gives Bacharach a lyricist again, an older wiser punk who can serve the song with a balance of truth and bravado.

When Costello belted out George Jones’ “Good Year for the Roses” on his 1981 Country album, it was a cover, a tribute, a dignified pose and a statement of eclecticism. “The Sweetest Punch” on “Painted from Memory” is a new thing entirely, the completion and success of a deepening that Elvis had been after for years. Before the song’s chorus, he sings of his partner casting off her wedding ring:

You dropped the band, I can't understand it

Not after all we've been through

Words start to fly, my glass jaw and I

Will find one to walk right into

You knocked me out

It was the sweetest punch

The bell goes...

The wit on display is all Elvis, but Costello becomes clever like Cole Porter, instead of clever like Moriarty. Bacharach’s ability to give glorious form to “the bell” materializes the love being pined for, which then in turn lifts Costello’s voice to a new register of deeper emotion. This unbridling peaks with the album’s inspiration and closing track “God Give me Strength”. The climax of the song, is written in the voice of the woman wronged:

Maybe I was washed out like a lip-print on his shirt

See, I'm only human, I want him to hurt

I want him

I want him to hurt

Through the female voice, the lyric finds Elvis in naked confession. He no longer uses language to protect himself with an innuendo or turn off the phrase that would tilt the playing field in his favor. The imagery and alliteration in the lyric are in service of emotion, not ego, and Costello sings the rawest sentiment of his career. Look how he resurrects the love betrayed by withholding the last two words from “I want him to hurt”. After all the transgressions, she still wants him. It gives her final switch to aggressor all the more impact. Costello breaks through a career of artful griping to create a throbbing tragedy. With Bacharach’s aid, the love is conjured up enough to be touched, and then lost. It makes all the difference. Costello soars upward on the last word, a leap into exposure. On the descent, Bacharach receives him with the most delicate of his flugelhorn arrangements, bringing the heartbreak into balance. The punk reaches out and grows up.