Bad Company “Here Comes Trouble”

In 1992, a decade after they’d traded their sublimely gifted lead singer (Paul Rodgers) for Ted Nugent’s former frontman (Brian Howe), Bad Company were in the waning hours of their second sunset. But somehow, three decades later, I find myself more than a little impressed with their final salvo. It's not so much that “Here Comes Trouble” is exceptional—it’s absolutely not. But rather that it is exceptionally good. It is both what I expected—professional, middle of the road, twenty percent softer than Hard Rock—and also a complete surprise—melodic, pleasurable, immaculately recorded songs that locate the exact midpoint between Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is” & “Jukebox Hero.”

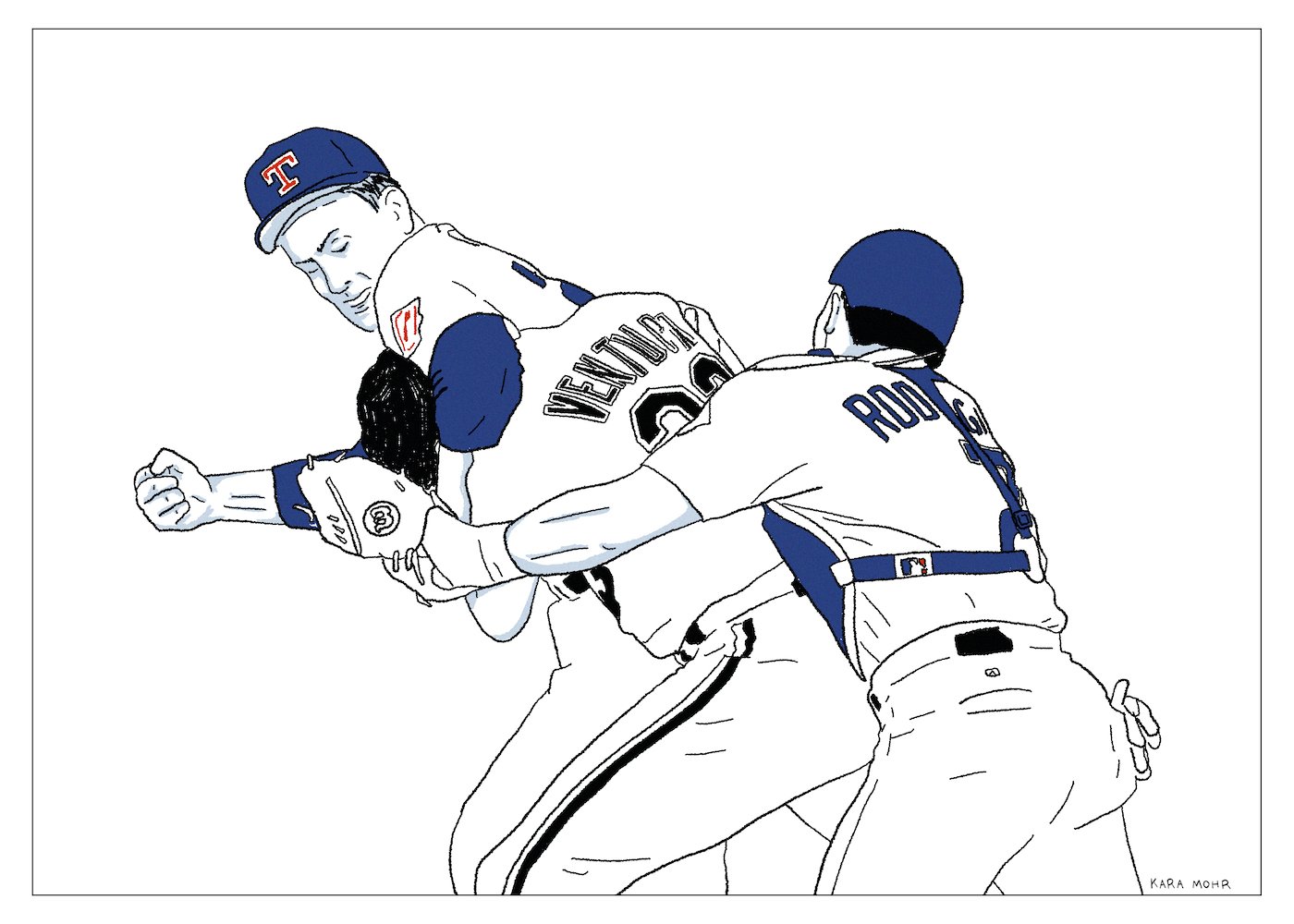

Robin Ventura “The Misremembrance”

His “grand slam single” during the 2000 NLCS would have been the most memorable event from almost any other player’s career. So would have the two grand slam game or the two grand slam double header. So would all those gold gloves. And that’s not to mention anything of the fifty-eight game collegiate hitting streak. Any one of those feats would have been a career hallmark for most ballplayers. But not so in the case of Robin Ventura who, on August 4, 1993, dared to charge the mound inhabited by one Nolan Ryan.

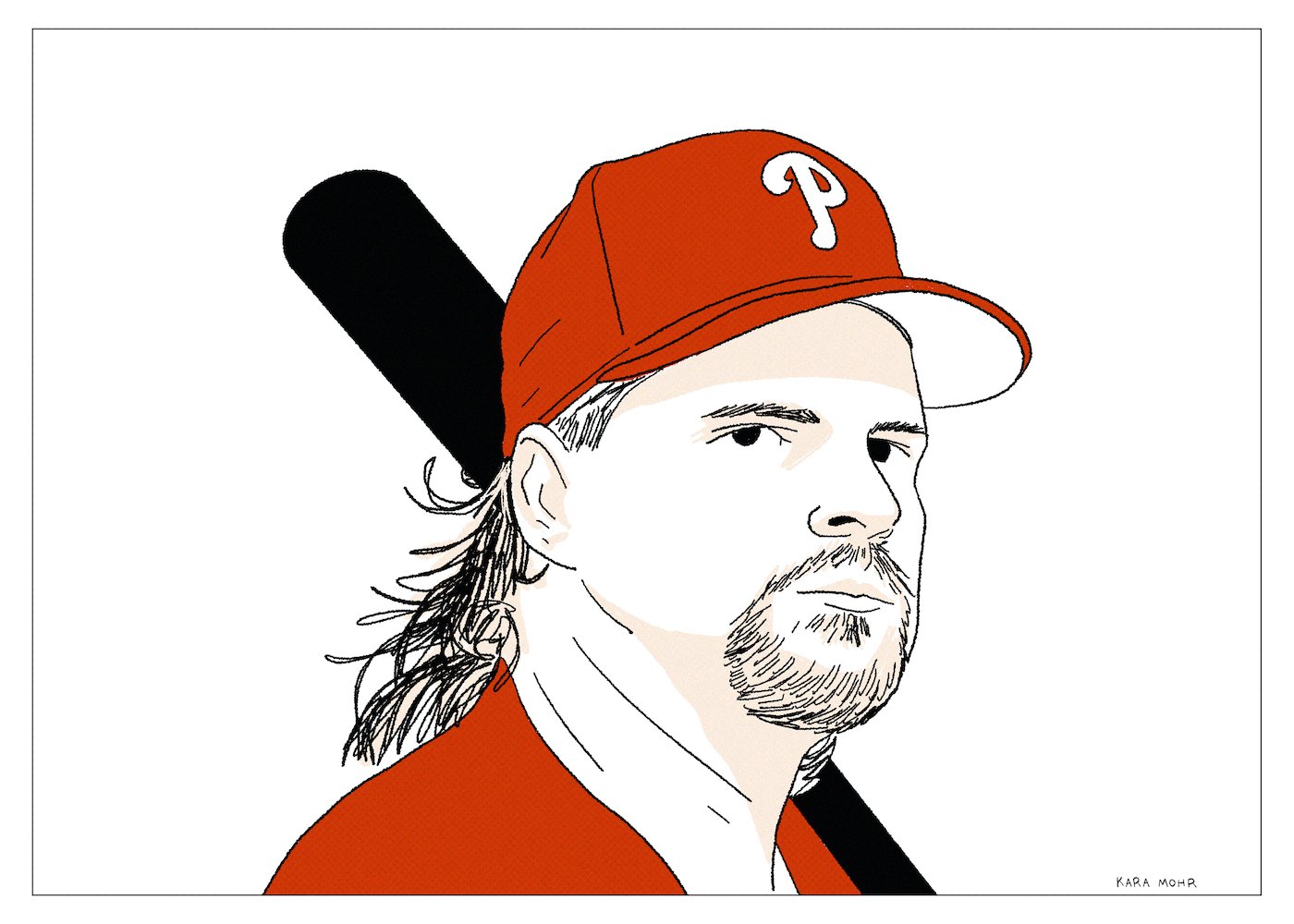

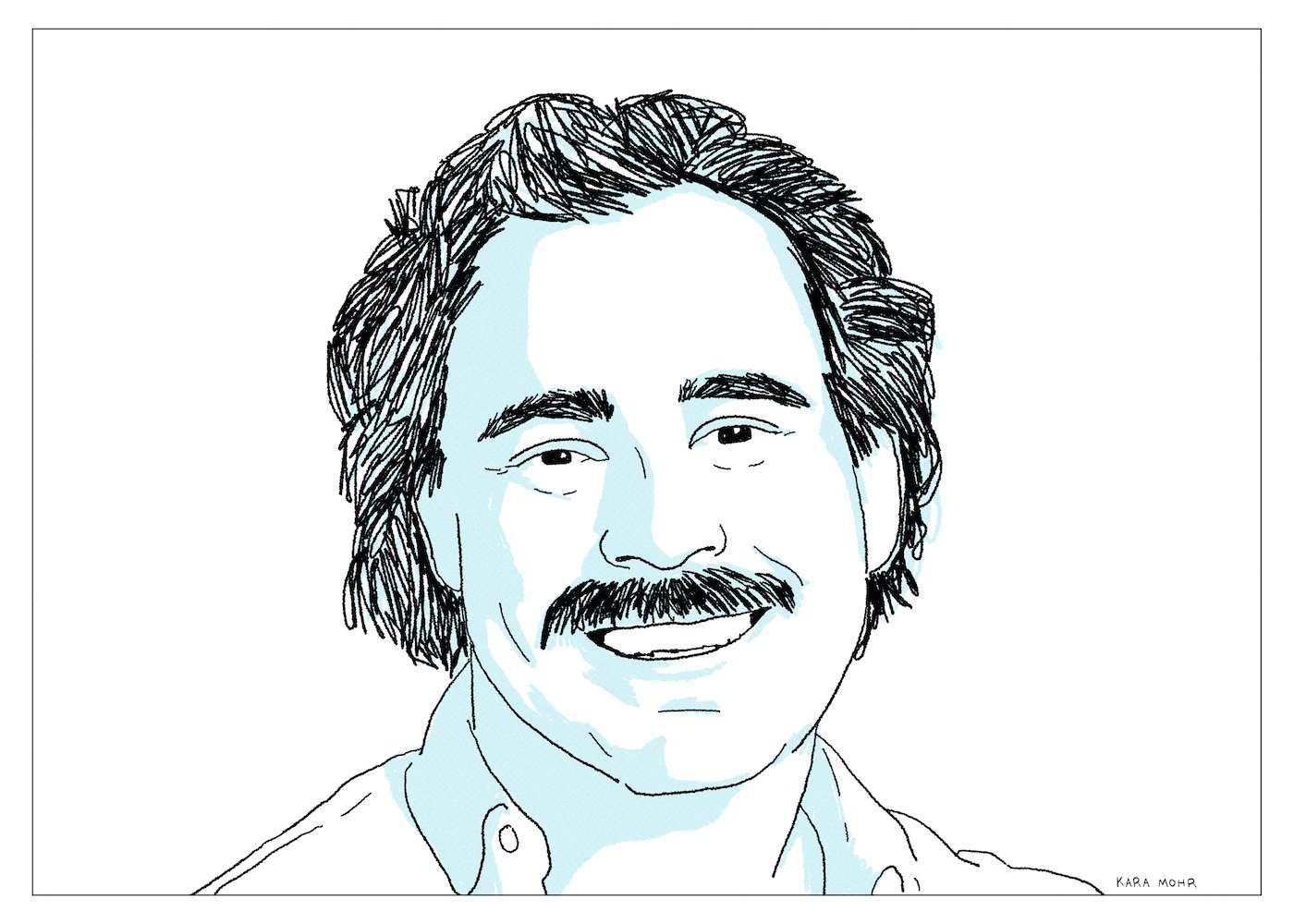

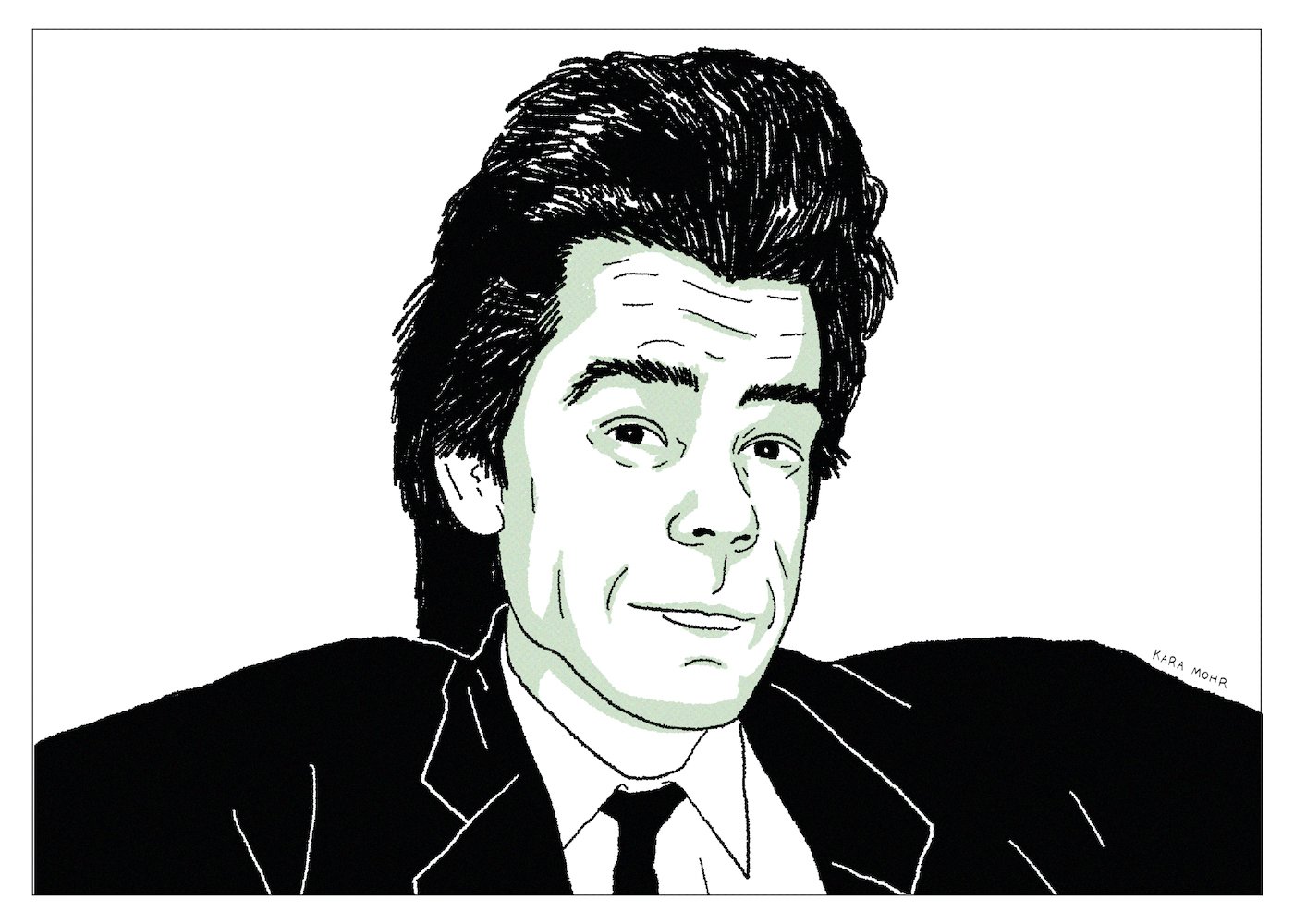

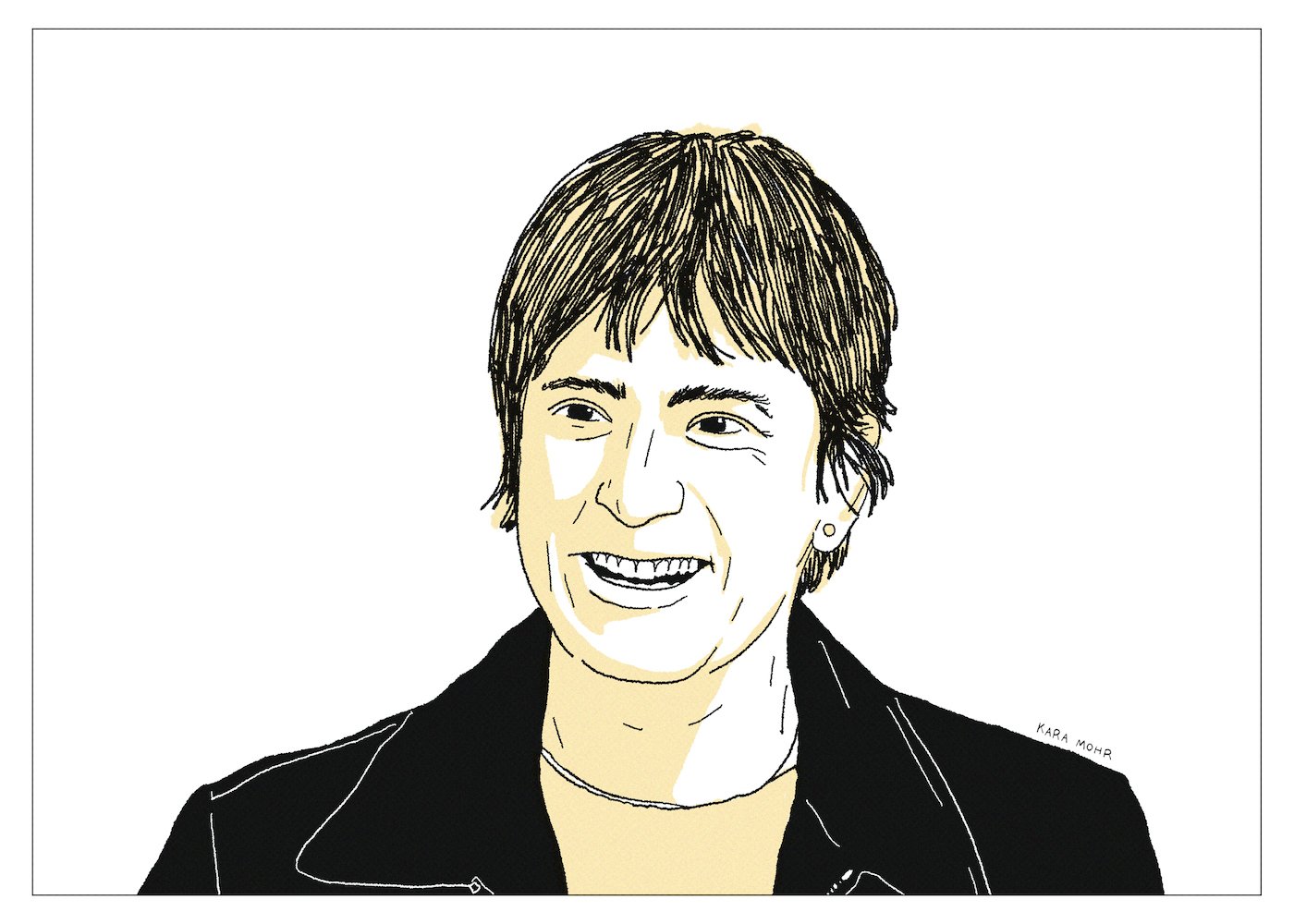

John Kruk “The Mullet Gives You Permission”

In 1972, President Richard Nixon made a diplomatic visit to mainland China where he finally, formally recognized the Communist government. Conventional wisdom suggested that only Richard Nixon, with his unimpeachable anti-communist bona fides, could have made such a conciliatory move. In the case of Nixon and China, for the truth to be heard, a very specific messenger was required. Twenty one years later, baseball got its Nixon and China moment when John Kruk faced Randy Johnson in the third-inning of the 1993 All-Star Game. During that legendary, if swift, at bat, Kruk revealed a truth that had been suppressed for years and which he alone could effectively convey: baseball is terrifying.

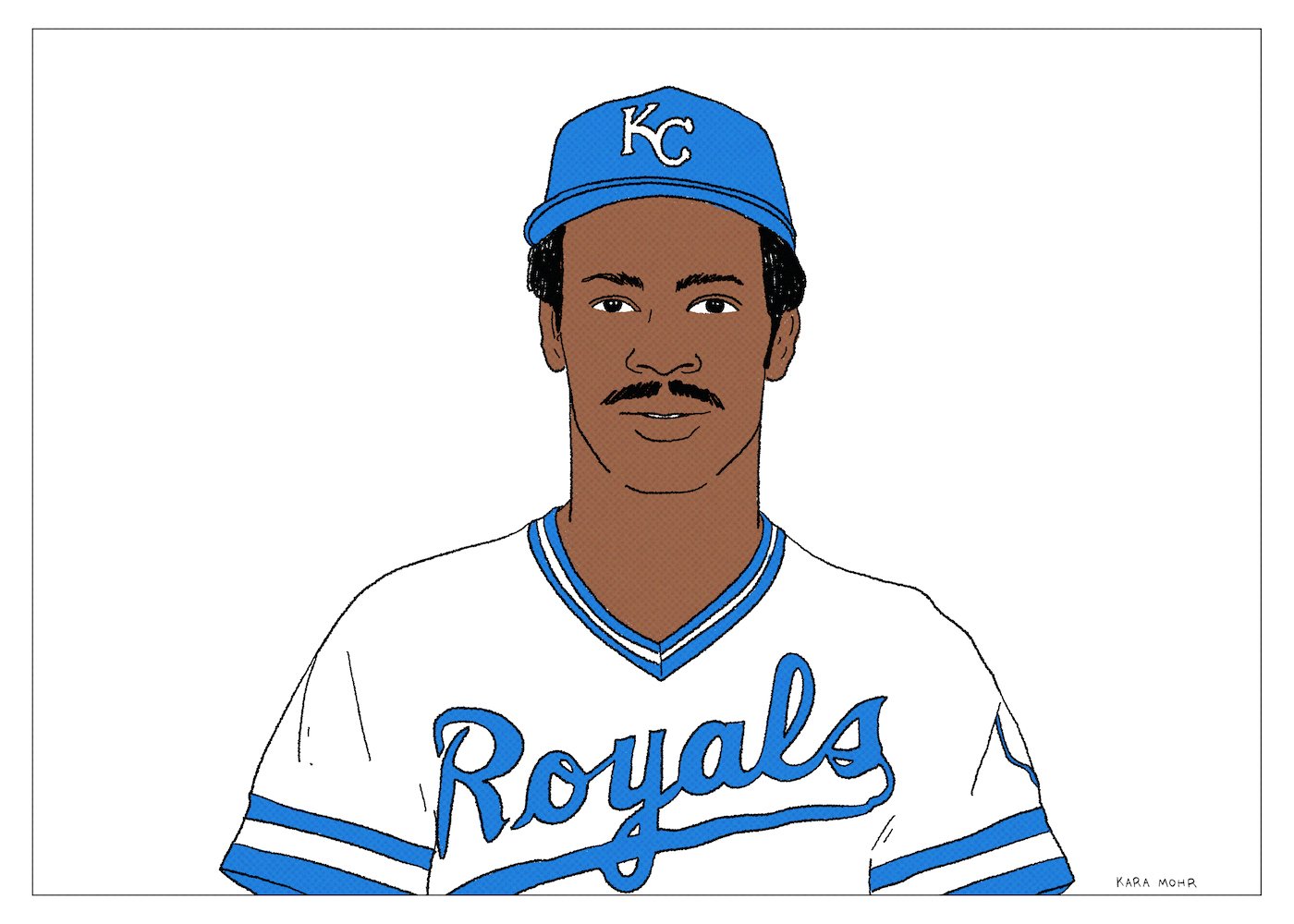

Willie Wilson “Speed Kills”

It is a cliche to suggest that, in life, your greatest blessing becomes your curse — that your feature becomes your bug. But in the case of Willie Wilson that seems especially true. So gifted, so fast and so strong, Willie could have been an All Star in most any sport. But the sport he chose was the one which least suited his particular genius. There’s a certain tragedy in knowing that you can surely do things that no one else in the game can do, but at the same time knowing that those things only matter so much in your chosen game.

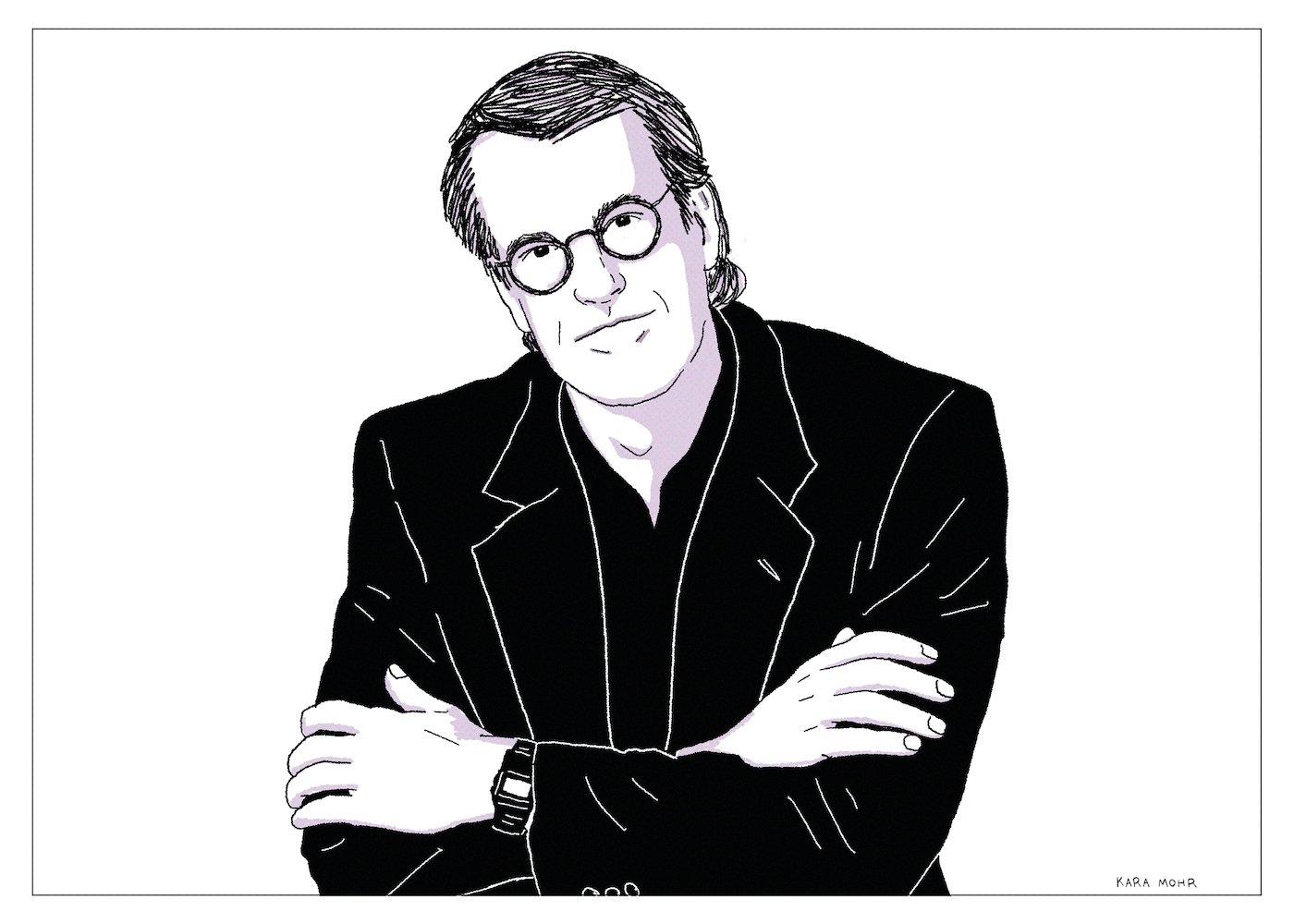

John Tesh “Live at Red Rocks”

Recorded in the summer of 1994, “Live at Red Rocks” first aired on PBS in the Spring of 1995 and hit stores just a few months later. In the thirty plus years since, it’s become synonymous with both “Nineties New Age” and “PBS fundraising.” Which is to say that it is simultaneously elaborate (not minimalist or tranquil) and cheap (free with donation). As an album of recorded music, it is almost farcical. But as a concert movie, it's positively gripping. For one windy night, against an breathtaking backdrop, accompanied by the Colorado Symphony Orchestra, and dressed in a three piece purple suit, John Tesh — the co-host of "Entertainment Tonight" — thrilled a rapt audience of dedicated philanthropists and Olympic gymnastic enthusiasts.

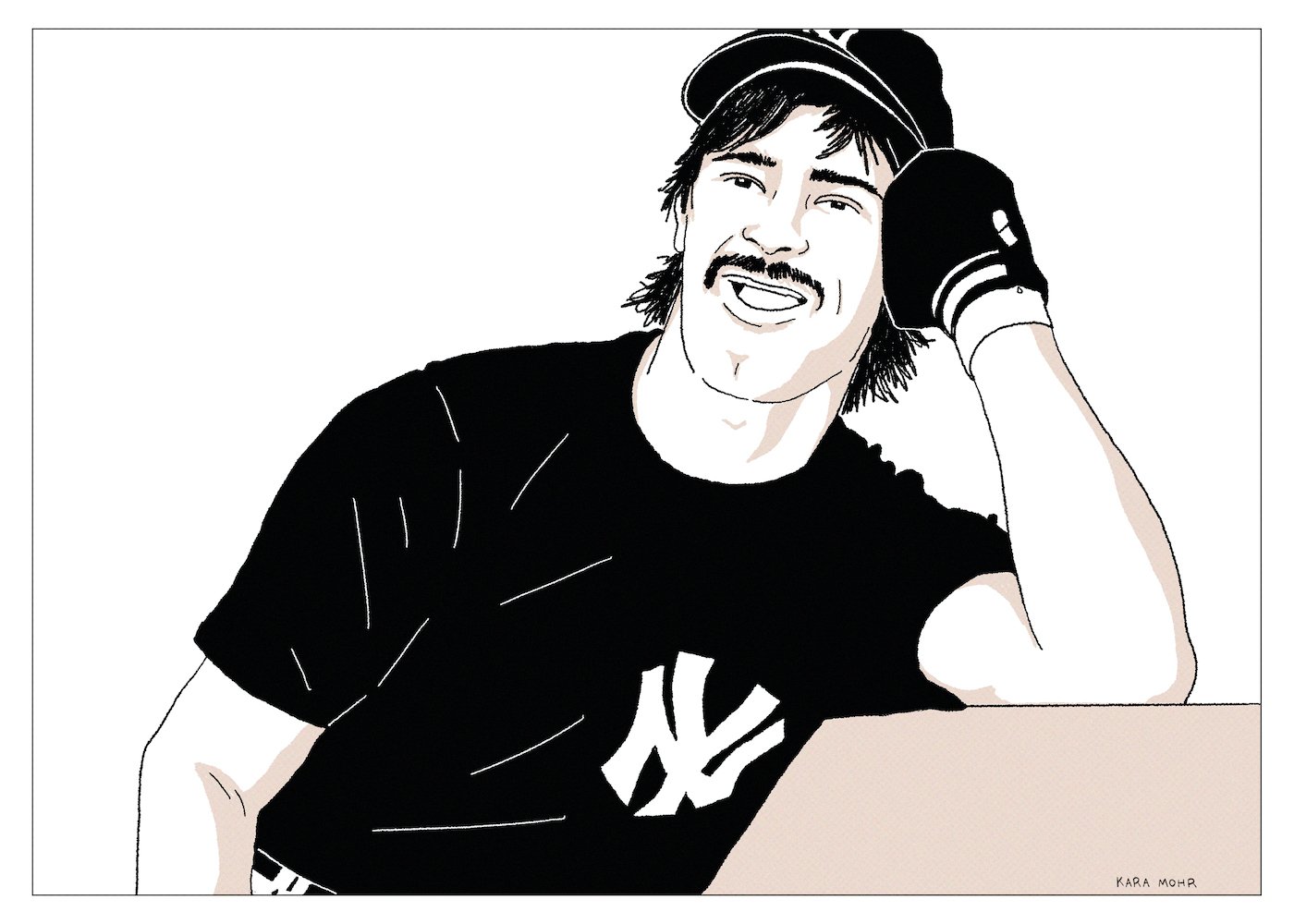

Don Mattingly “The American Dream”

By the time Don Mattingly became the Yankees’ captain in 1991, the franchise had already won twenty-two World Series championships. They’d not won one, though, during Mattingly’s career. In fact, they’d not even been to the Fall Classic. But during his final season in 1995 — a season in which he limped his way to seven home runs and 49 RBIs — the Bronx Bombers finally made it to the playoffs. According to the story of The American Dream, Donnie Baseball’s work ethic should have been validated by a championship ring before he was put out to pasture. And, true to form, he tried. The badly hobbled Mattingly — as one last testament to the power of will and determination — hit .417 for the series with six RBIs and a magical go-ahead home run in Game Two. But, in the end, the Yankees lost, Mattingly retired and returned to his horse farm in Evansville. The next year, without Mattingly, the Yankees would win the World Series. And then again three more times in the next four years.

Jimmy Buffett “Fruitcakes”

Buffett’s eighteenth studio album was both his first to reach the top five on the sales charts as well as his first Platinum-seller since the 1970s. Its title is a nod to fans — those sun loving, clothing optional weirdos who sometimes get drunk and say silly things but who possess a positively essential joie de vivre. It almost goes without saying that most Parrotheads are not clothing optional weirdos. But it’s also worth saying that many of the teachers, lawyers and middle-managers that comprise his fanbase do fantasize about being carefree, clothes-free beach dwellers. And that is precisely Buffett’s appeal — how he taps into a primal need to escape. An urge to — every once in a while — exist in a liminal space between feeling warm and feeling nothing at all.

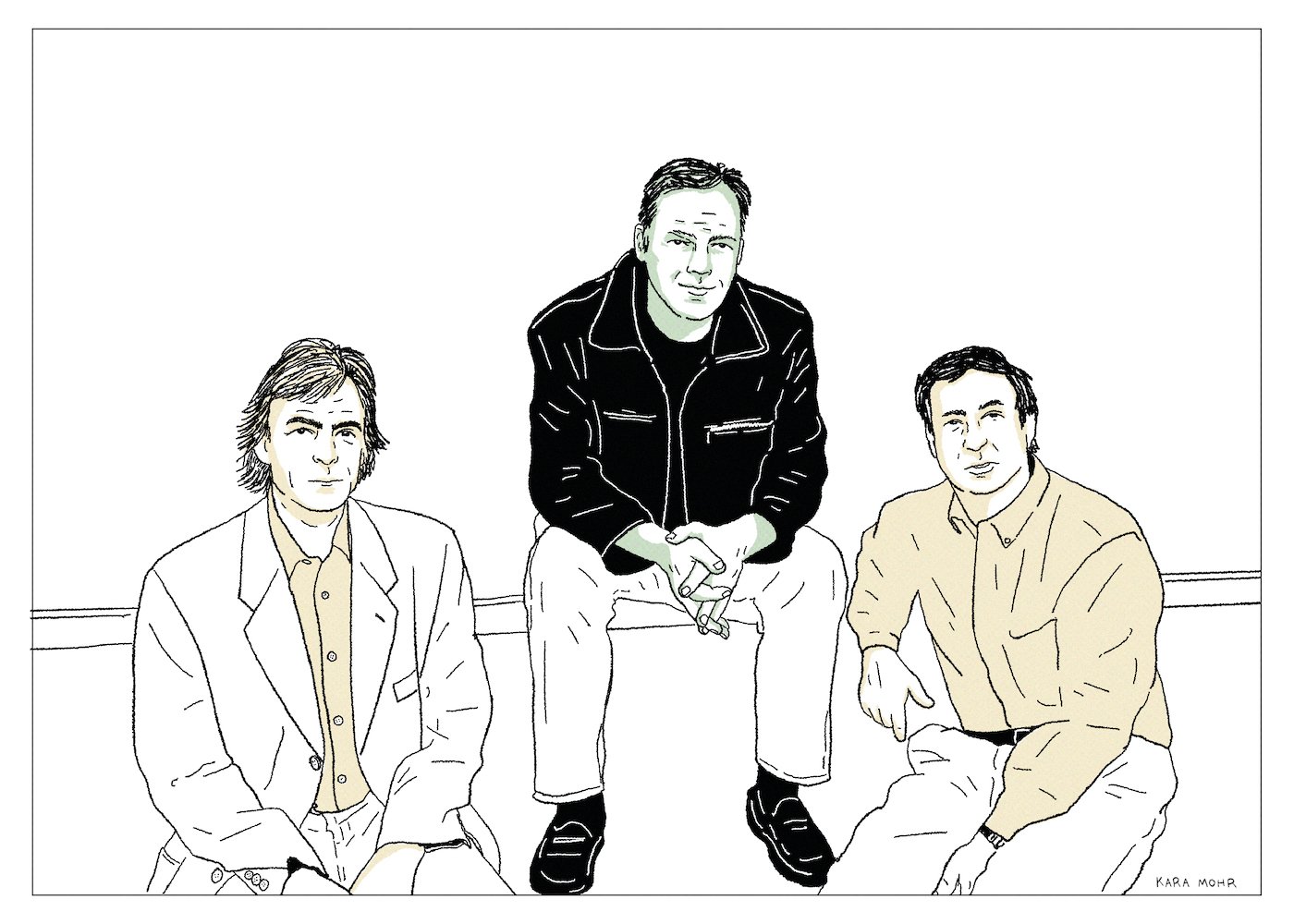

Pink Floyd “The Division Bell”

For as much as it was a David Gilmour album, “A Momentary Loss of Reason” was also a Roger Waters’ album. Every single review noted the absence of the band’s erstwhile leader, who was himself active and vocal in sharing his derision for the project. And while the record was commercially successful, it was doubly taxing. In its aftermath, Gilmore and Waters finally and painfully resolved most of their legal affairs but almost none of their enmity. For many years there was little hope, and no indication, of any future for Pink Floyd. But then, in 1993, the ink having barely dried on both his marital and professional divorces, Gilmour did something unexpected. He invited Nick Mason and Richard Wright—the latter of whom had been dismissed from the band during the making of “The Wall”—to get together, play some music and talk about the power of talking.

Steve Earle “I Feel Alright”

In 1996, having shaken off five years of rust, sixty days in jail and a couple decades of addiction, Steve Earle released “I Feel Alright.” Whereas 1995s “Train a Comin’” found him looking backwards, “I Feel Alright” was a completely present album. It was vintage Earle, after the pink cloud had dissipated—honest, aching, and feeling “alright.” Which is to say he was not feeling great. But also he was not feeling awful. It was a hedge—somewhere between cautious and optimistic. “I Feel Alright” is the ultimate one day at a time response to the question, “How you doing?” As a description of Earle’s state of mind, it sounds appropriate. As a title for his sixth studio album, it feels like a radical understatement.

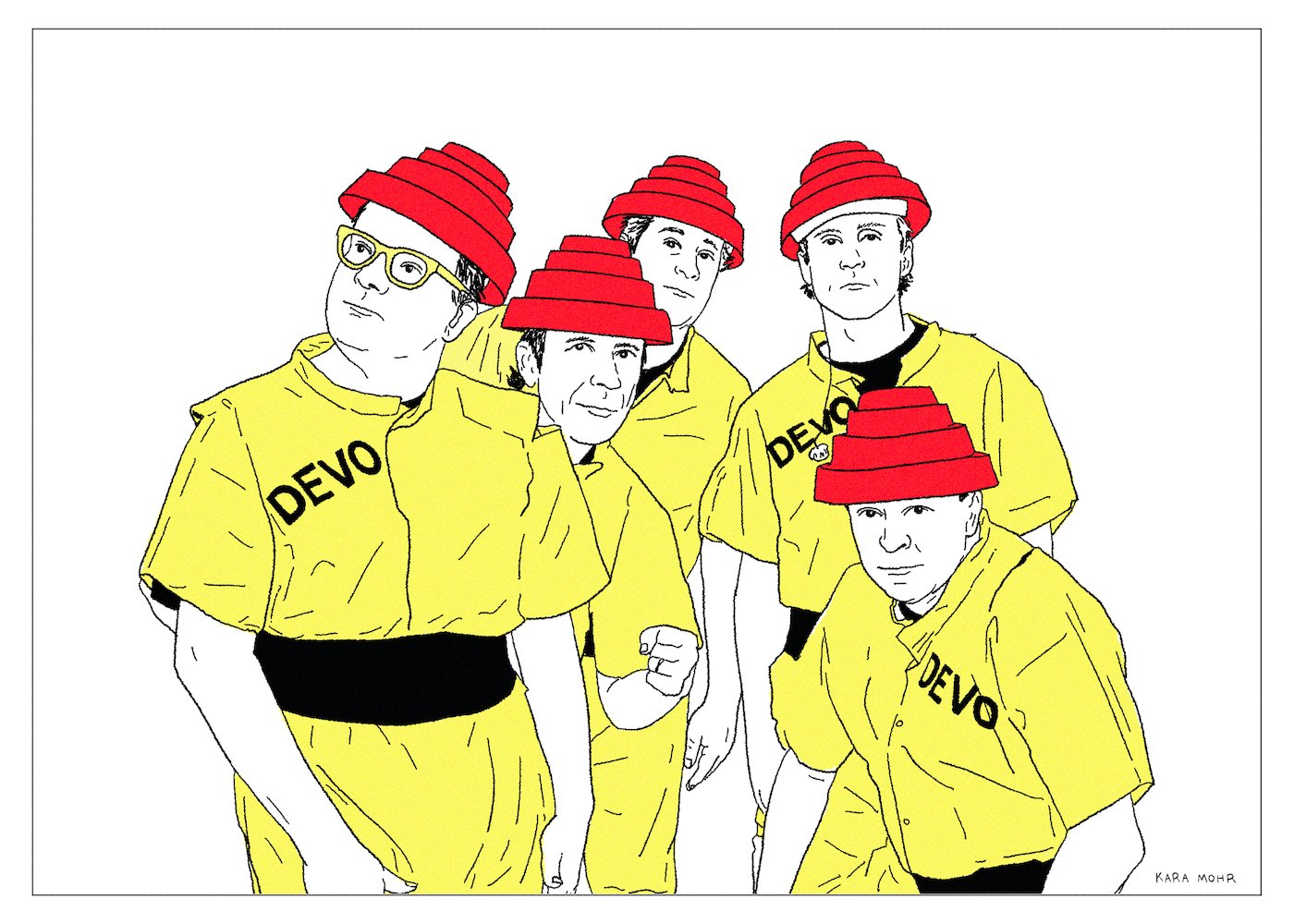

Devo “Smooth Noodle Maps”

Shortly after Mark Mothersbaugh scored “Revenge of the Nerds II: Nerds in Paradise,” but long before he worked on “Rushmore,” Devo was in flux. Dropped from Warner Brothers, they signed to Enigma Records, a label that specialized in crossover Metal, first rate, second wave Punk and just barely mainstream Art Rock. On paper, it seemed like a perfect fit. Unfortunately for both parties, “Total Devo,” from 1988, arrived with a thud and a sigh. If their Enigma debut anticipated the band’s break-up, though, “Smooth Noodle Maps,” from 1990, sealed it. The first Devo album not to chart in any English speaking country was not so much a commercial or critical failure (though it was both of those things) as it was something that Devo had never, ever been accused of. It was boring.

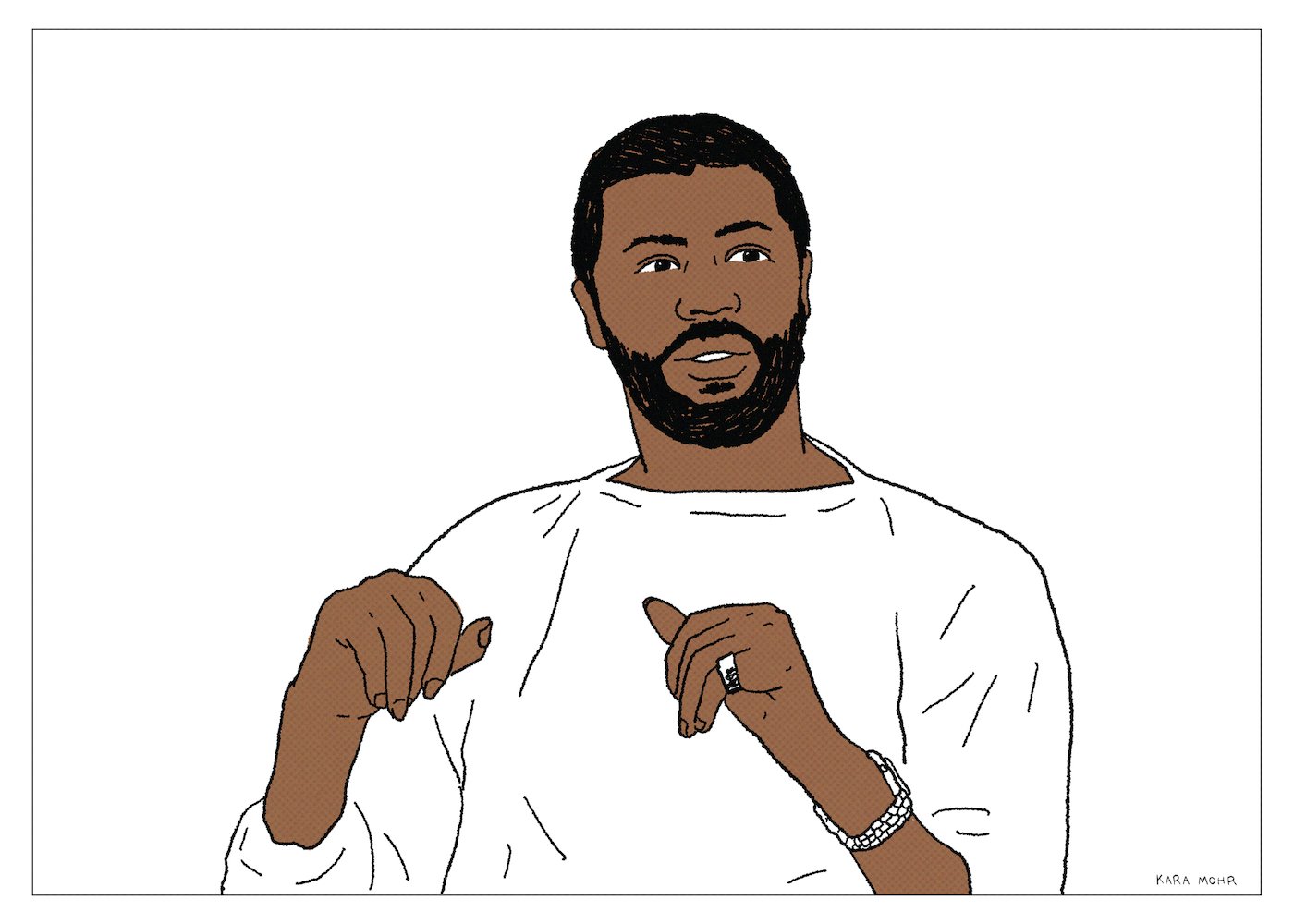

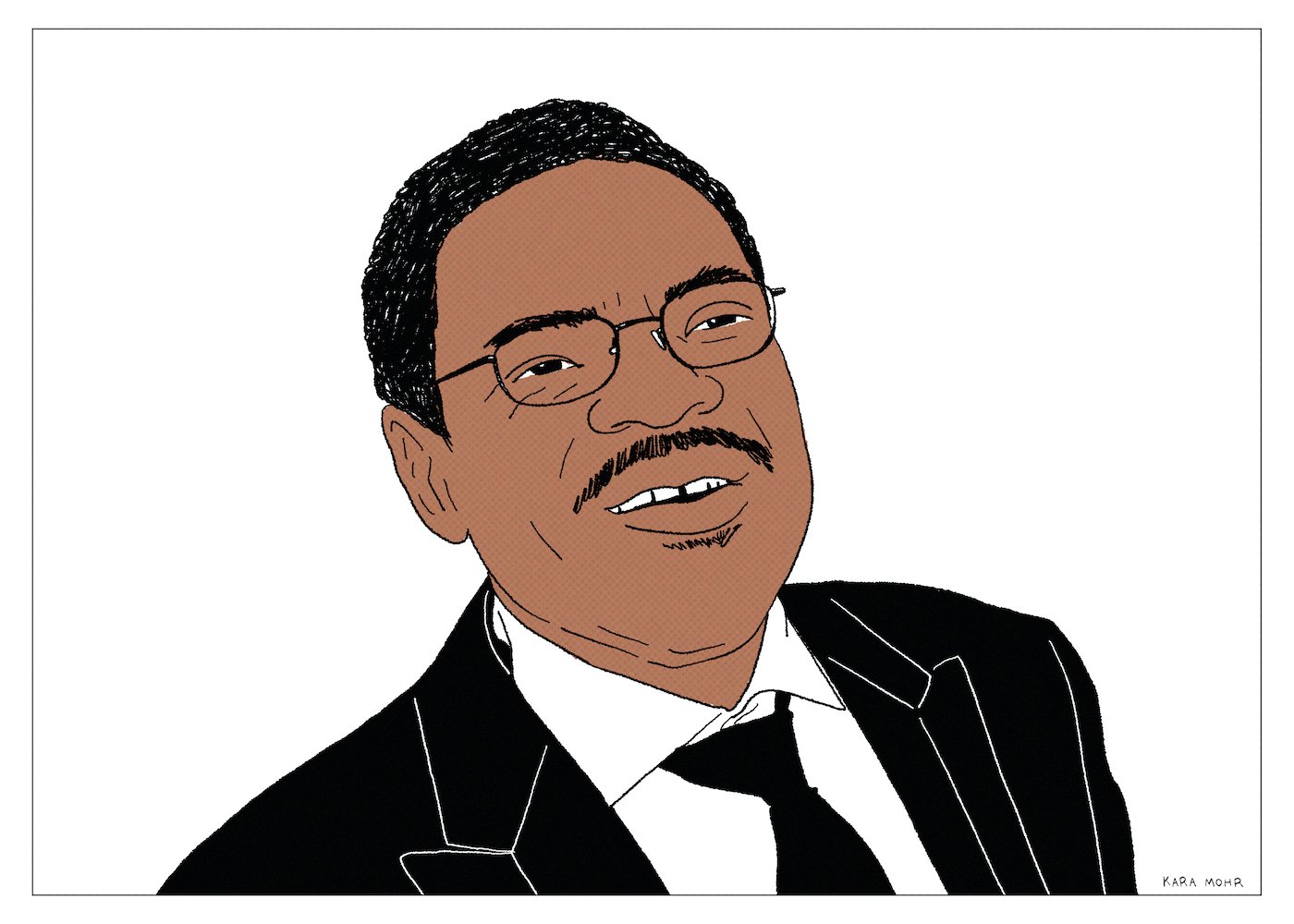

Teddy Pendergrass “Truly Blessed”

That was the conundrum Teddy faced in in the late Eighties — if and how to sing about sex from a wheelchair. After his accident, he was still a young man, closer to thirty than to forty. His sparkling smile was intact. His face was unscathed — in fact, he looked as handsome as ever. And while it is much harder to sing while seated, it is by no means impossible. As for everything else — the gliding onstage, the bend of the hips, the undressing, the working up a sweat, the showering and the burning hot oils — those were a lot more complicated. But Teddy did the work and made the transition. No, he was not the same person who drove a Maserati to perform at an arena full of women. He was something much less iconic but also much more sympathetic. He was an underdog — a redemption story.

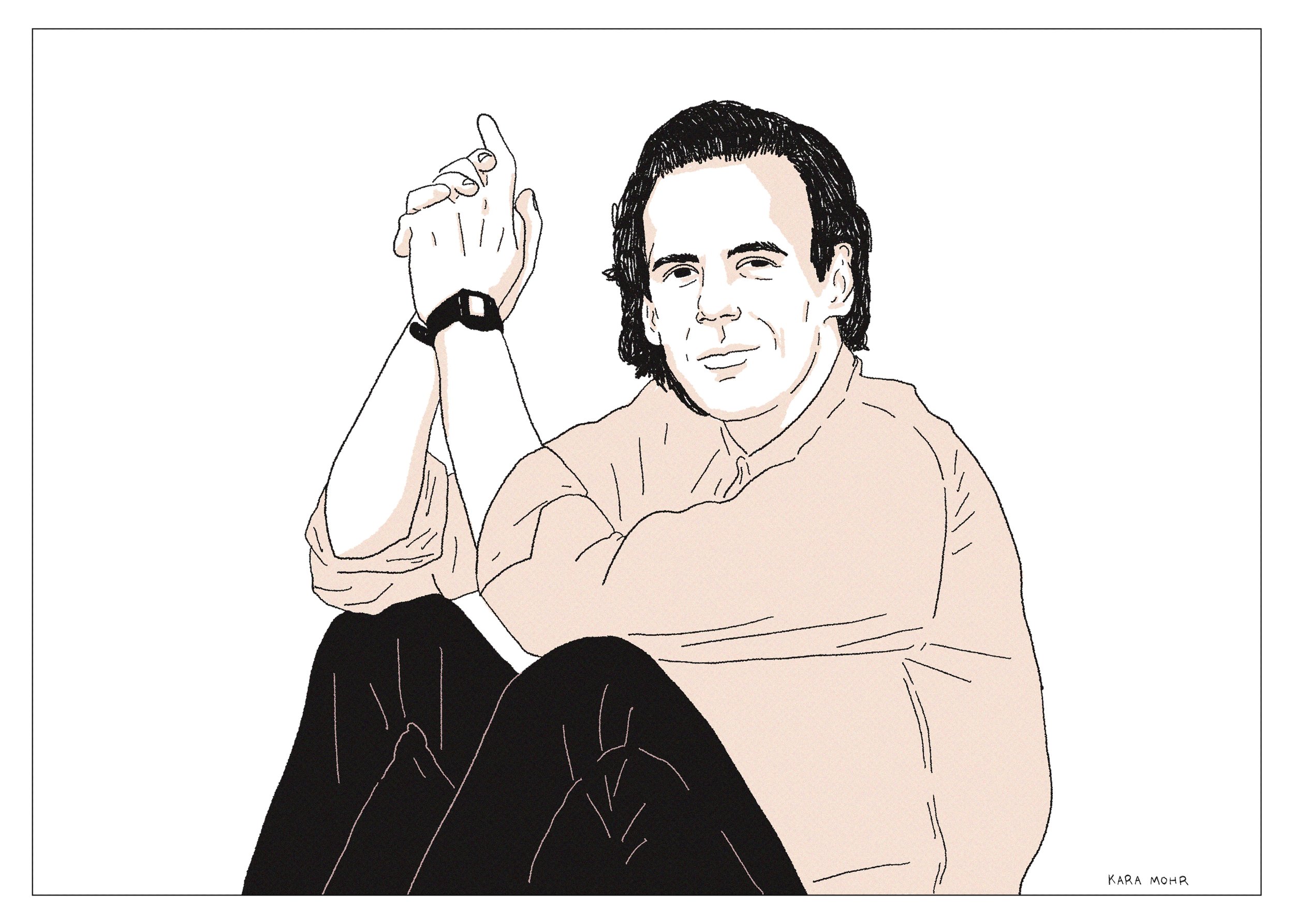

Todd Rundgren “No World Order”

By 1992, Todd Rundgren — the guy who kind of, sort of invented Power Pop, who sang like Carole King, who could play any instrument, and who made Meat Loaf sound like a bat out of hell — was a middle-aged, former Rock star, former producer, father of two living in Marin County, California. If he’d proven anything during the previous decade, it was that he was deeply interested in the intersection of music and technology and largely disinterested in his own commercial prospects. Which meant that, if you were Warner Brothers Records, based in Burbank, California, and trying to sell a lot of albums, you probably wanted to steer clear from him. But, if you were Philips Electronics, based in Amsterdam, and you wanted to promote your new CD-i (compact disc interactive) players and discs, Todd Rundgren was definitely your guy.

Michael McDonald “Blink of an Eye”

There’s an aphorism that goes something like, “Brad Pitt is a character actor in a leading man’s body.” In music, there’s no direct equivalent for the Pitt aphorism. There are, of course, shy or mercurial singers — Bob Dylan and David Bowie fit that bill. But, solo artists, almost by definition, cannot be reluctant frontmen because they have no “back” to blend into. They are not part of a group — they are the show. The same applies to lead singers in bands, albeit for different reasons. There is really no such thing as a grudging frontman. A lead singer has to want it. Privately, they can be shy and awkward like Farrokh Bulsara, but when they hit the stage they have to be Freddie Mercury. That’s how it works. But, like all statutes, there are very rare exceptions. In the case of Rock and Roll frontmen, there is one indisputable outlier — a guy who sounds like Bob Seger and Darryl Hall at the same time. Who, once upon a time, looked like the love child of bearded, post-Beatles McCartney and a soul puppy. A guy whose voice is as rich as a yacht but who always preferred to be in the background, heard more than seen.

Buster Pointdexter “Buster’s Spanish Rocketship”

The prevailing discourse has always been that Buster Pointdexter was “the act.” That the tuxedo, giant pompadour, martini glasses, Jump Blues, and Eighties Club Med by way of Fifties Havana vibes was David Johansen having a go at everyone. That ten years after the demise of The Dolls — the world’s greatest band that never had a chance — and years after working his way around the world with the David Johansen Band and ending up exactly where he started (nowhere), he needed to make us laugh so we wouldn’t cry. Buster Pointdexter was supposed to be a serious good time, but also in no way serious. It was a gag. A costume. Closer to Tenacious D than to The Dolls. But what started out as a lark — a mildly embarrassing side hustle even — became a career. What’s more, Buster was not a phase. He was not an alter ego or an id. Looking back now, Buster Pointdexter was the thing.

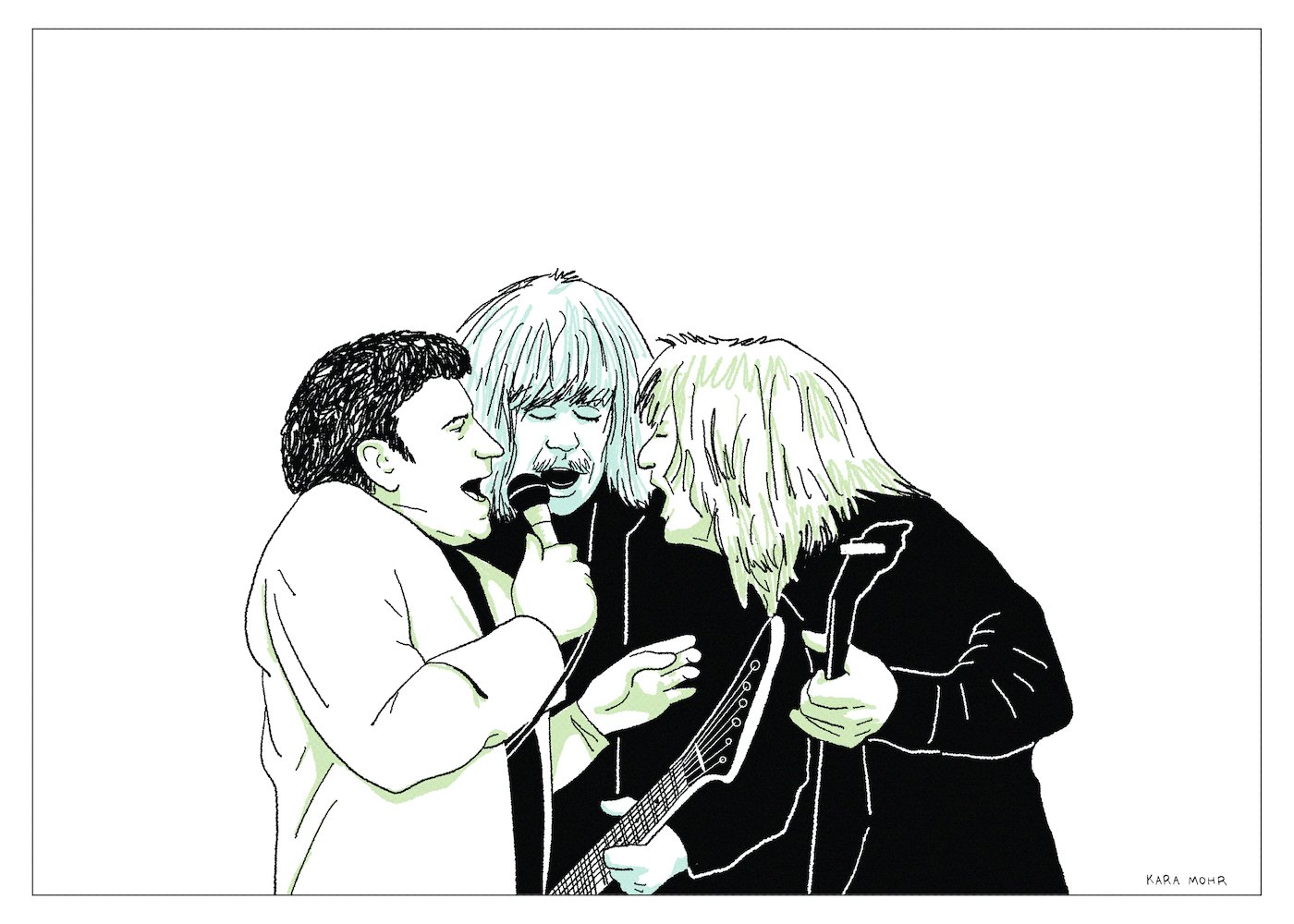

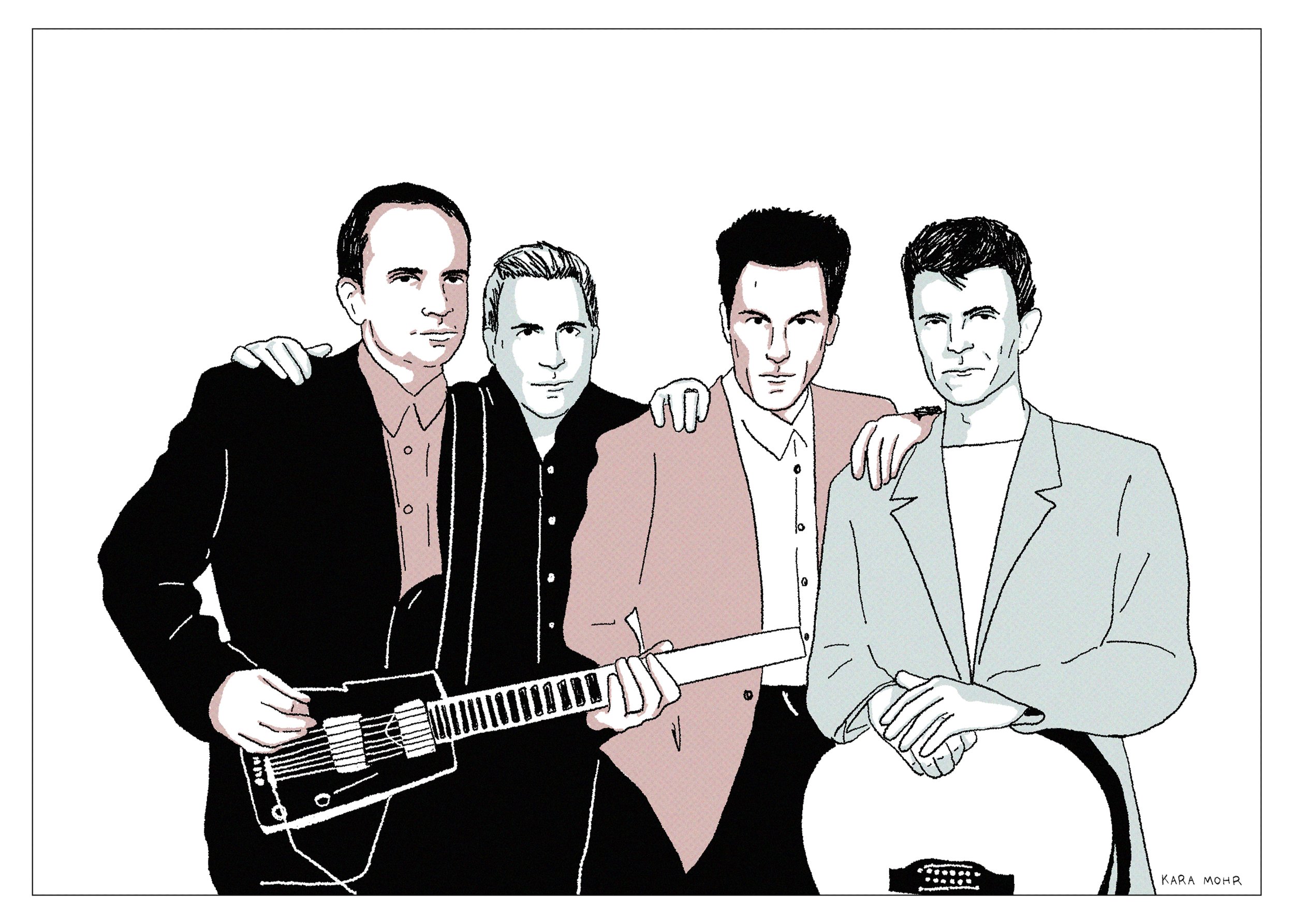

Styx “Brave New World”

Like Queen, with whom they’ve often been compared, Styx has always been the kind of band that swings for the fences. Most of the time they whiff — but in a charming “love the effort” sort of way. When they connected, however, as they did roughly one time per album between 1973 and 1982, they hit it out of the park. Way out of the park. During that run, DeYoung, Shaw, Young and the Panozzo brothers scored a half dozen top ten hits and five consecutive platinum-selling albums. And yet it always seemed to me that the band was a mistake — that we already had Queen and Journey. That DeYoung should be wowing audiences on Broadway (which he eventually did) and that Shaw should be fronting a Hair Metal band (which he also eventually did). By the end of the Nineties, seventeen years removed from the dystopian, sci-fi hit that broke the bank and the band, Styx were still swinging, but no longer connecting.

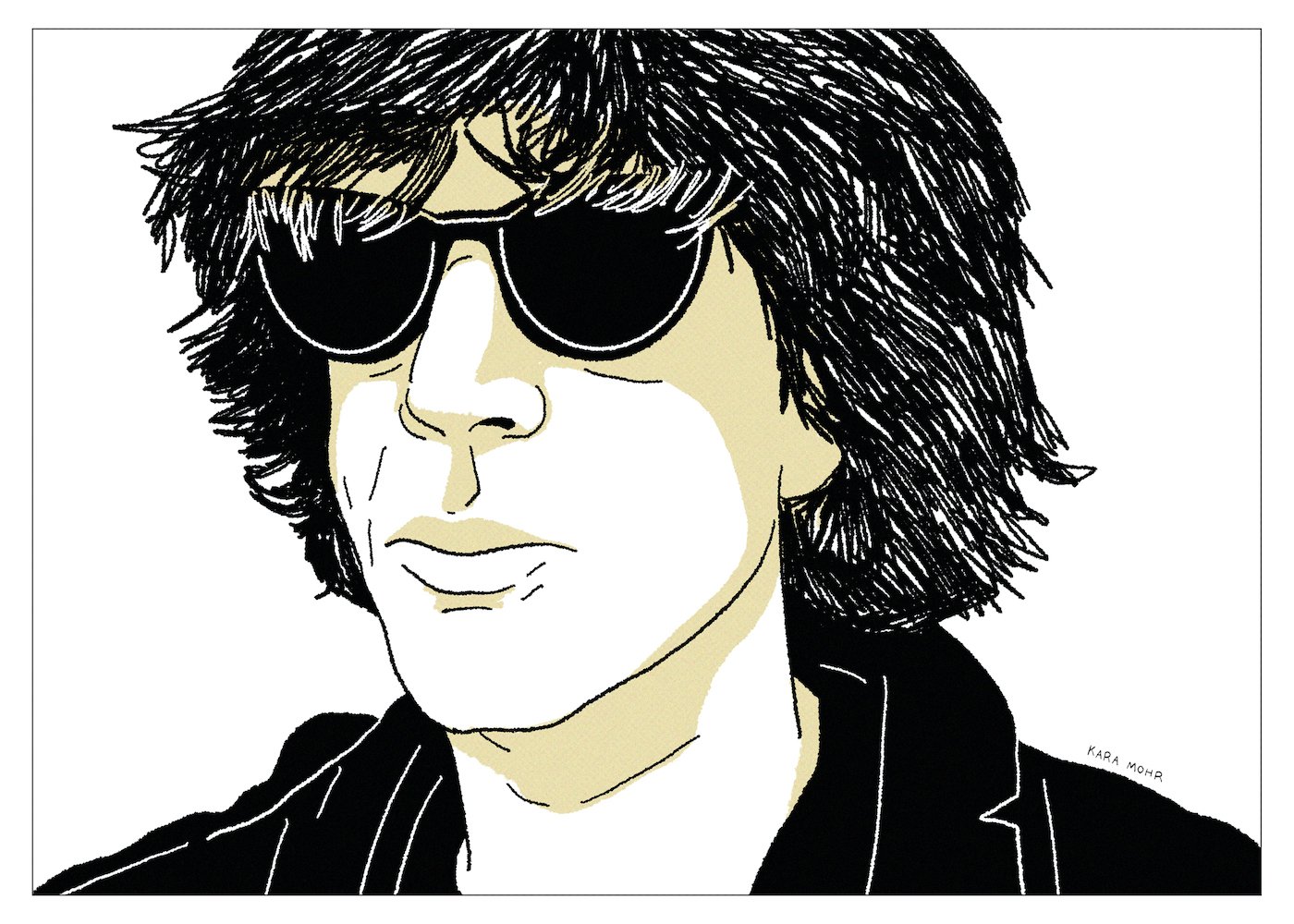

Dim Stars “Dim Stars”

Though it was released in 1991, “Dim Stars” sounds like New York City in 1988 — when Jon Spencer was fronting Pussy Galore and before Sonic Youth got a major label deal and when Avenue A was still sketchy and when everything stunk of imminent recession. Like all of those other things, you could call “Dim Stars” loose and offhanded, or you could call it sloppy. You could call it artful or avant garde, or you could say that it sounds like shit. But in fact, it really sounds like four different things. One, like Sonic Youth with Richard Hell splitting the difference between Thurston and Kim. Two, like a poorly made sequel to “Destiny Street.” Three, like an overqualified Scuzz Rock band that had not yet found its groove. And, finally, like a post-structuralist hipster cover band.

Billy Preston “You and I”

If 1979 marked the end of Billy Preston’s run as a Pop star, it was a beautiful finish. “Late at Night,” his first record for Motown and his last of the decade, found The Fifth Beatle after dark, conjuring a quiet storm. “With You I’m Born Again,” the album’s hit single, was a duet with Syreeta Wright that explained everything from Barbra Streisand to Luther Vandross. By 1982, however, “Billy Preston the superstar” was done. Lionel Richie, Prince and, mostly, Michael Jackson, had taken over his corner. The new music spigot was shut off. Guest work dried up. And, one day, the ubiquitous sideman found himself buried under a mountain of cocaine and bad decisions. And so, in 1997, as legal and financial problems mounted and rumors and innuendo swirled, Preston escaped six thousand miles from the bright lights of Hollywood into the open arms of a past prime Italian Electro Pop group named Novecento.

Rob Thomas “Chip Tooth Smile”

While I have been guilty of my fair share of Matchbox Twenty eye rolls, I was also guilty of not really knowing much about the band. They were always something of an enigma to me — a mystery that I couldn’t shake. Except, it wasn’t really the band I was interested in — it was their frontman, Rob Thomas. I had read all the facts (Wikipedia) and heard all the albums (four with Matchbox Twenty and four solo), but I still had zero clue. Was he more Adam Duritz or Ed Kowalczyk or Stephan Jenkins? Or was he my generation’s answer to Phil Collins and Lionel Richie? Generally speaking, time is the enemy of Rock and Roll. But it’s a dear friend to writers. Time furnishes us with perspective and evidence. It reveals lies and truths. It separates bad style from bad music and characters from their settings. Also, as Rust Cohle once suggested, time is just a flat circle. Time was very much on my side as I followed the investigation to its logical conclusion — Rob Thomas’ 2019 solo album, “Chip Tooth Smile.”

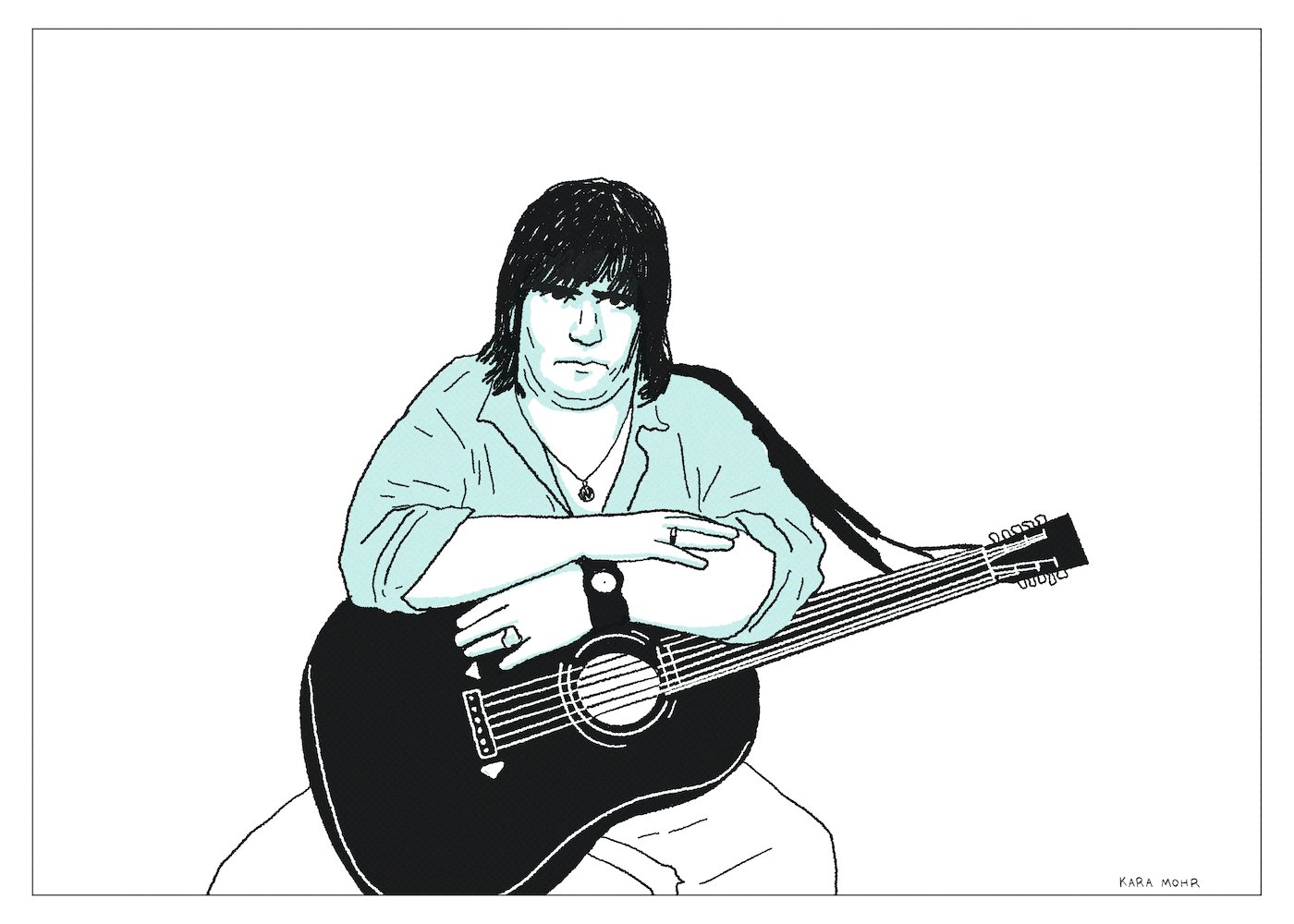

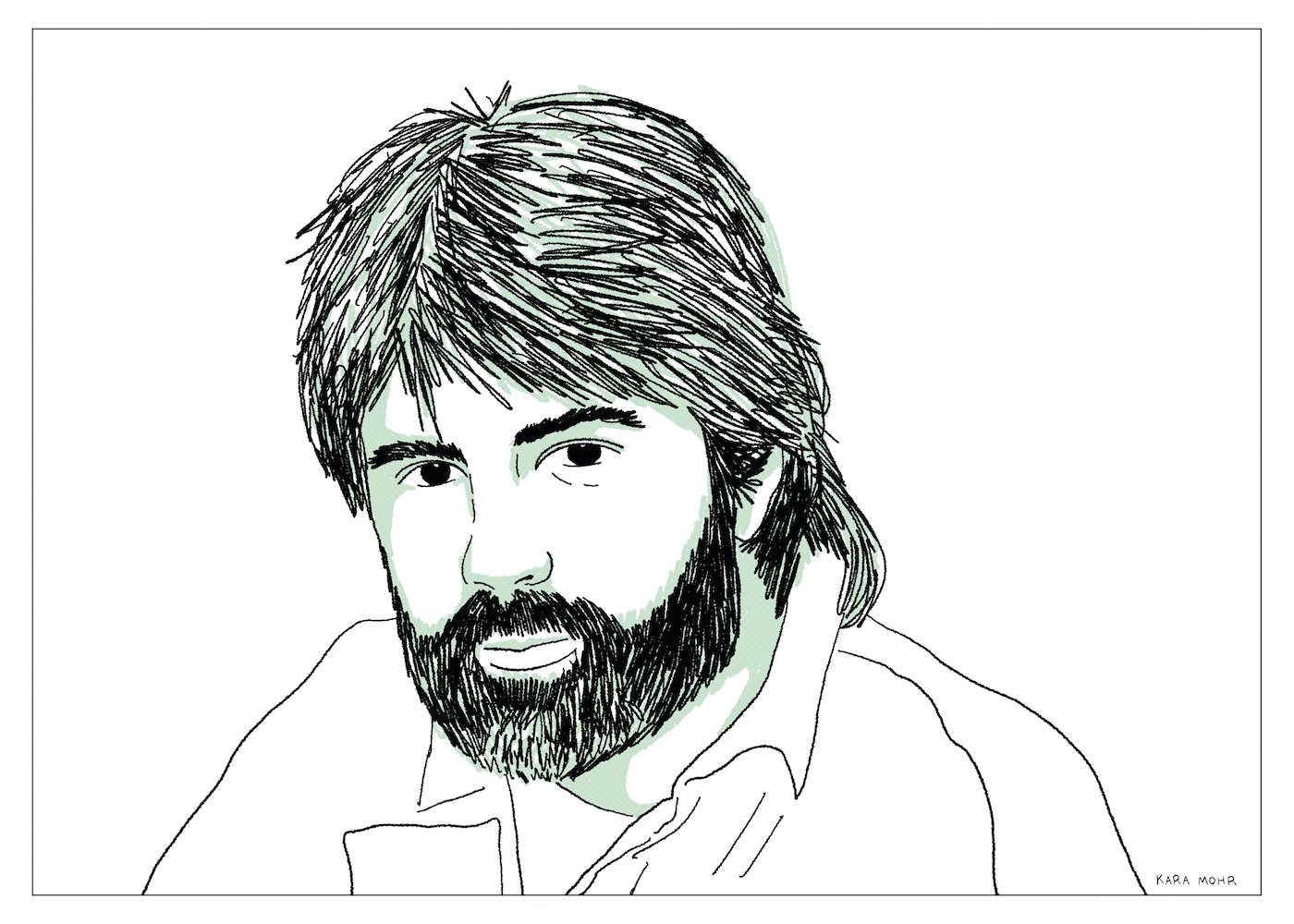

John Hiatt “Perfectly Good Guitar”

There’s a concept in child rearing — and I’m honestly not sure if it’s armchair psychology or actual science or what — called “perfectly adequate” parenting. Its premise is radically simple: that parents should be no more or no less than their child needs. One the one hand, it makes a lot of sense. On the other hand, nobody really wants to be “perfectly adequate.” Not in parenting. Not in life. Not in work. And, certainly, not in music. Pop music is defined by highs and lows. By mania and soul. The road in between is longer, and oftentimes much harder. It’s a workmanlike path — one that is rarely disruptive or revelatory, but is eventually, and amazingly, just right. Richard Thompson is always perfectly adequate. Sometimes more. Never any less. John Prine. Lyle Lovett. Nick Lowe. Always perfectly adequate. But of all the singers I can think of, the one who is most truly perfectly adequate — whose skill is evident, whose records are solid and whose faith and commitment is unwavering — is John Hiatt.

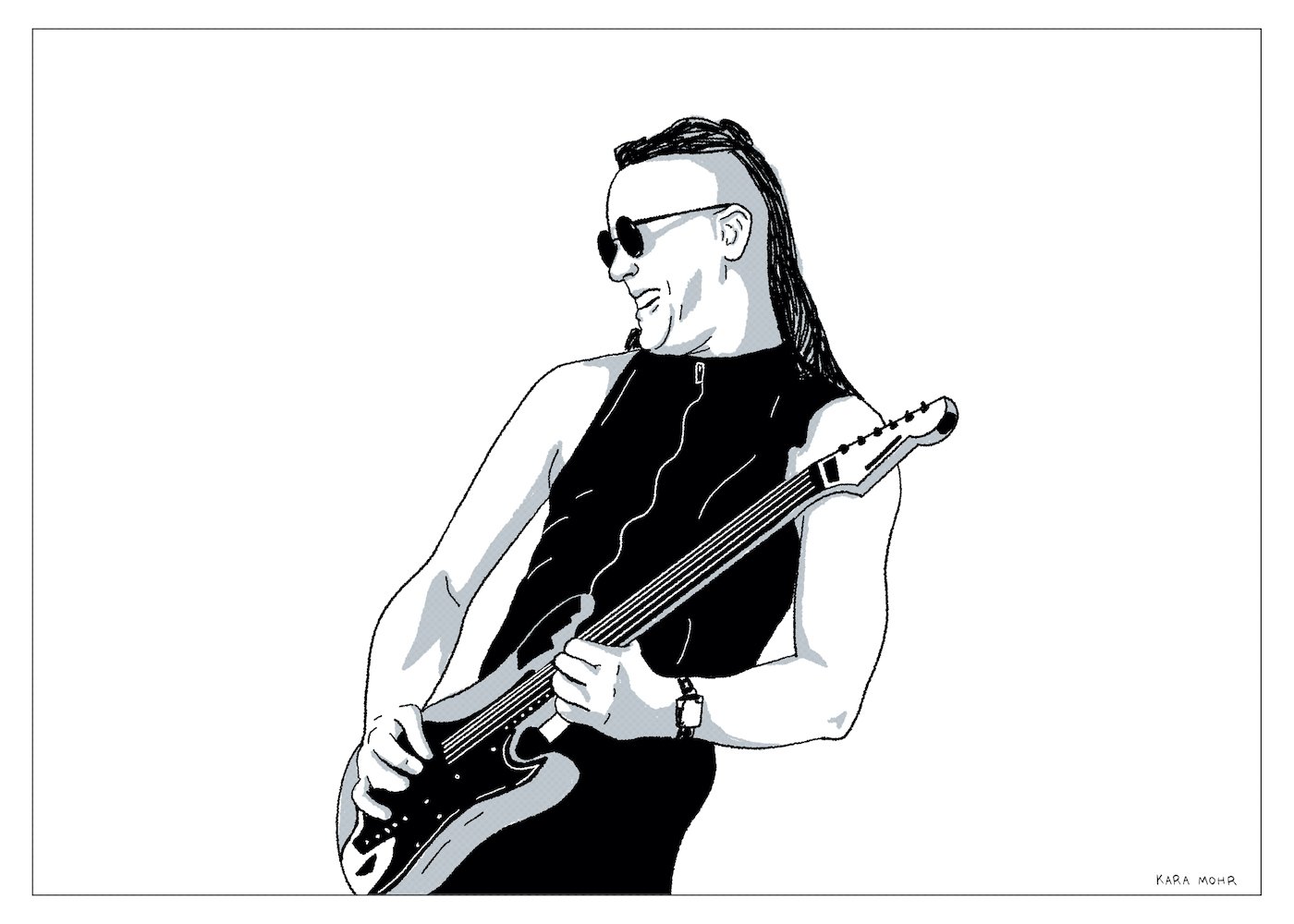

Tin Machine “Tin Machine II”

By the late Eighties, there were no fresh blood for David Bowie — the greatest vampire in Rock and Roll — to suck. The top Rock radio songs of 1988 included Henry Lee Summer’s “I Wish I Had a Girl” (what? who?), Bruce Hornsby and the Range’s “Valley Road” (rocks so light) and Tommy Conwell & The Young Rumblers’ “I’m Not Your Man” (not a typo, I checked). After two consecutive duds, Bowie was desperate for inspiration, but the pickings were slim. And so, he did what desperate people do. He found the nearest available guy and went all in. No research. No courtship. He just needed a guy with a beating heart, pumping blood and some capacity to make music. But mostly, he someone who could be a willing host to a brilliant parasite. Reeves Gabrels was that new host. And, in spite of his regal sounding name, he was truly just a guy — a guy from Staten Island, New York, who happened to be married to David Bowie’s tour publicist. One day, Gabrels was playing steel guitar in Rhode Island for a band called Rubber Rodeo. A year later, he was the cofounder of Tin Machine.