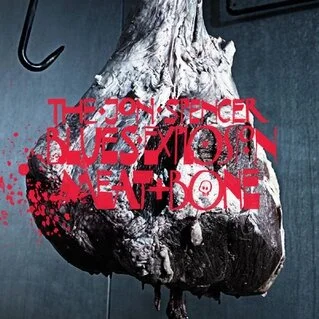

Jon Spencer Blues Explosion “Meat + Bone”

Most things decay. They decompose or rot. Or both. Obviously, this is not news. And in spite of how mightily we resist it or how strenuously we look away, it still happens. It’s perfectly natural. Depending on your perspective, decay can be sad or it can be ugly or it can be beautiful or, even, artful. Tooth decay comes for all of us and there’s not a whole lot to like about it. We brush and floss but we still end up in the dentist’s chair cringing at the mention of plaque. That’s the mildly depressing and gross kind of physical decay. But, there are also white hairs or deep lines in our faces that communicate wisdom. Similarly, there’s urban blight and all of the socioeconomic suffering it signifies. But, there’s the art of graffiti and the promise of rebirth in grand, old cities. Most often we mourn decay. But — yes — there are times and places where it is celebrated. Bryan Sansivero is a photographer who published a book called “American Decay,” full of abandoned, old homes, rotting to their foundations. There’s peeling paint, sickly taxidermy, rickety pianos and piles of unwashed dishes. And, yes, the images are strikingly sad. And, yes, they are also quite beautiful.

“American Decay” is basically rot, aestheticized. This pretense is not exactly new. To the contrary, it’s become part of the postmodern artistic lexicon. There’s rot in the kitsch of early John Waters. There’s rot in Roger Corman and Dario Argento and the entire history of B-movies. There’s sharper, if less funny, rot in the fashion of Punk. And, if you go deeper, through the kitsch and beyond the irony and the style, you arrive in New York City in the late 70s and early 80s. You travel past “Taxi Driver” and Teenage Jesus and The Jerks and No Wave. And then, by the eighties, you find yourself in The Cinema of Transgression, with Nick Zedd and Richard Kern. There, the film stock is probably stolen. The images might feel pornographic. The production value is zero. Everything is set in the hopeless vacancy of a city that was recently bankrupt. There is nothing cute about it. It’s the stuff beneath the decay. It’s scuzz. It’s what happens when art willfully decomposes to its basest form.

This was the gunk that Pussy Galore waded into when they arrived in lower Manhattan, around 1986. By then, the city was gentrifying in some parts, but more slowly downtown. Led by a doe eyed college grad with a semiotics degree and a sordid -- now legendary -- cast of noisemakers, the band was as much conceptual art as it was Rock and Roll. Pussy Galore shared some genetic material with No Wave and Big Black and The Cramps and Einstürzende Neubauten. But, really, they were a more theoretical answer to a theoretical question: “What if The Rolling Stones had rotted to their core on the streets of New York in the 1980s and if Andy Warhol filmed the whole thing?” Pussy Galore was R&B so fully deconstructed that it could be hard to identify anything that resembled a song beneath the ashes and rubble. There’s a shard of a chord here. The squeal of a vocal there. The shrapnel of a beat somewhere. But, really, it’s all just body parts pulled from the corpse.

Predictably, the band broke up after a few years. In their wake, as New York began to sparkle again, Jon Spencer formed his new band -- The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. A three piece, with two guitars and no bass, the Blues Explosion initially picked up not far from where Pussy Galore left off. In between his two bands, Spencer did some time with Psychobilly outfits, where he developed a love for Crypt Records and their faster, louder, three chord songs. Yes -- actual songs. So, by 1991, when he, Judah Bauer and Russell Simins formed JSBX, it was immediately clear that Spencer’s second band would be more muscle on this corpse than his last one. The band’s debut stayed true to the Crypt Records formula -- twenty songs, recorded on as few tracks as necessary, and clocking in at under two minutes per track. Some of the songs were produced by Kramer and some by Steve Albini. To casual listeners, if there were any in 1992, it sounded a good deal like Pussy Galore. But, if you really leaned in, you could detect a semblance of structure and maybe even a hint of groove. Most notably, where Pussy Galore was grimey, the Blues Explosion was sweaty. It was still Art Rock. It was still R&B deconstructed. But it was also serious as a heart attack.

In the early 90s, New York was a Rock and Roll graveyard. Hip Hop was exploding. There was Metal and Hardcore across the bridges and under the tunnels. But independent Rock music was almost nowhere to be found. And, what was there, was not especially good. The city was amazing. But, at least musically, it wasn’t all that cool. Yo La Tengo were still just a sleepy band from Jersey. The Beastie Boys had moved to LA, where Beck was doing things. And if, like me, you wanted Indie Rock, you went to Chicago, Seattle, Portland or Austin. So, for the first half of that decade, even though they were miles away from the preciousness of Indie Rock, the Blues Explosion were the most interesting band in “The 212.”

While Pussy Galore collapsed under the weight of their own noise, Jon, Judah and Russell managed to lift their new group up and out of the squalor. During their early years, JSBX were, by almost any definition, an unpopular band in a shitty music scene. They were friendly with the Crypt Records bands -- The Lyres, The Gories and The Oblivions. But, they didn’t actually resemble them. Compared to their closest peers, The Blues Explosion were more conceptual and more interested in R&B than Rockabilly. In spite of their name and their appreciation for the form, they were also not a Blues band. They sounded more like the high falutin noise that soon emerged from the Fort Thunder scene in Providence (Lightning Bolt, Les Savy Fav, etc.). Whatever the band was in 1992, it was loud, fast and confident. But it was also a work in progress.

“Extra Width,” from 1993, changed all that. The Blues Explosion’s third album was released on Matador, the esteemed home of Pavement and Superchunk. Its cover featured a portrait of the band’s handsome, if tired, lead singer in a sport coat. The typeface was big, bold and legible. If Pussy Galore was the music of high urban blight, “Extra Width” had the look of early gentrification. The music followed suit. The songs were longer, steadier paced and far more structured than anything Jon Spencer had made before. Moreover, his vocals were mixed forward and he’d committed to an affect that he’d only flirted with before. Previously, Jon Spencer squealed and hollered like Mick Jagger more than he crooned like Elvis. He sounded desperate and tortured. But, sometime just before May of 1993, he codified the new persona. It was part itinerant preacher, part hype man and part carnival barker. He retained the black denim jacket and the greasy hair of his youth. But, scrubbed up ever so slightly, he resurfaced as perhaps the most handsome man in Rock and Roll. Dark eyes. Five o’clock shadow. Square jaw. Thin but not lanky. Flanked by an equally beautiful wife, Jon Spencer was an unmistakable leading man. He was Billy Crudup handsome. Behind him, on guitar, was his Steve Buscemi. And behind the character actor was the muscle on drums -- the deadpan enforcer.

“Extra Width” wasn’t a commercial windfall, but it was a massive step forward for the band. After a couple of years working it out, the trio was fully locked in. “Afro” stuck the riff and added swaggering wah-wah to the guitar. “Soul Typecast” opened with a religious invocation and then nailed an honest to goodness groove, under which Spencer squealed and howled. “Big Road” hammered a single chord for four minutes while the singer rattled off the names of exits from the New Jersey Turnpike. The album was a brazen flex. It retained the boisterous spirit of Spencer’s earlier work, but with a fresh coat of paint. It was like an old building with a new owner. It was an alpha album made by men and for men who were probably more betas than alphas. And it would mark the beginning of a brief period wherein Jon Spencer was quite possibly the coolest man making Rock music — and also the easiest target.

In 1994, smack dab in the middle of the Alternative Revolution, JSBX released “Orange.” By this time, the spark of “Extra Width” had become a loud buzz. The band was popular enough to inspire great ambivalence. There were true believers — myself among them — who considered them to be an unparalleled live band. They played breathlessly. There were no set lists and rarely a break in between songs. Simultaneously, their albums were marrying something very primal and sexual with something very self aware, if not elevated. But to their critics, the band was a bad, probably offensive joke. They were convinced that the Blues Explosion was an appropriation in name, if not form, of Black music. That it was unmannered schtick, lacking the reverence of Eric Clapton or Stevie Ray Vaughan. That it was a snarky joke perpetrated by an overeducated, too handsome, white guy. That it was chauvinistic and oversexualized. To his credit, Spencer emphatically repeated that, while he loved the Blues, JSBX was not a “Blues band.” Other than that, however, he rarely gave substantive interviews. He didn’t take the bait. He tried to let his music do the talking.

“Orange” did just that. If “Extra Width” was a breakthrough, the band’s fourth LP was a validation of their surname — it was an explosion. “Bellbottoms” opened with a string section and the roar of a crowd. And then, for over forty minutes, the band made good on every hyperbolic promise they ever swore to. They sweat. They groove. They howl. They rock. The bump. “Orange” was the rare album that could only have existed in the moment after Nirvana but before Radiohead, when the Beastie Boys and Beck were the most important artists in the world. There were old school Hip Hop beats on “Orange.” There were screeching guitar noises. And there was a lead singer embodying Vegas Elvis, except with The King’s youthful good looks and vigor. In 1994, a lot of people were floored by “Orange.” Since that time, it’s been forgotten in some circles and reconsidered suspiciously by others. But, having been there then and having revisited it now, I can confirm — it’s a massive, unrelentingly great album.

For most of the mid-90s, JSBX was the band that hipsters and Hollywood wanted to see “happen.” Jon Spencer had friends and fans in high places and in far off, sub-popular places. He could work with Beck and The Beastie Boys or with Ghostface Killah or with Elliott Smith or Calvin Johnson. He could get Winona Ryder to star in his music videos. Magazines loved putting his photo on the cover. So, for a couple of years, the Blues Explosion kept getting bigger and bigger. They were not a mainstream act, but they were nearing the peak of indie celebrity. The cultural bricolage with which they built their new sound probably owed more to Quention Tarantino and The Dust Brothers than it did to Crypt Records. But, 1994 was the year of “Pulp Fiction.” And, spiritually, “Orange” was that film’s musical equivalent. If ever there was a moment for the band to happen, it was in that window, between 1994 and 1996. The grime in Jon Spencer’s hair that turned to sweat, had finally turned into a luxuriant sheen. Amazingly, though, and in spite of the conditions and the groundswell, The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion never really “happened.” “Orange” was their commercial peak. They never got their Gold Record. They were too early for “Pitchfork’s Best New Music.” They pre-dated New York’s Indie migration of the late 90s and early 2000s. And, eventually, they were market corrected by younger, simpler, less noisy Garage Rockers like The White Stripes, The Hives and The Black Keys.

Part of the Blues Explosion’s stagnation and regression was a matter of context. Just as they were ascending, Alternative Rock started getting less alternative. In the second half of the 90s, the radio turned away from Nirvana and towards Third Eye Blind. Part was a matter of taste -- the Blues Explosion were more dissonant and unbridled than anything on the charts. And some of it, of course, was driven by both personal and professional decisions that the band, themselves, made. Save for Jon, none of the members of the band seemed interested in doing press. And Jon was only barely interested. The bigger obstacle, though, may have been the creative choices that the band made after “Orange.” At the moment just before the Garage Rock revival, when the Blues Explosion were driving on precisely the right course, they seemed to intentionally redirect themselves. With “Now I Got Worry” and “Ass Pocket Full of Whiskey,” they stripped away some of the big beats, glamour and studio trickery from “Orange” in favor of something more straightforward. Both albums -- the latter fronted by legendary bluesman, R.L. Burnside -- were strong records. The band was in full control of their considerable powers at the time. But they marked a downshift in momentum.

“Acme” followed in 1998 and it sounded partially sanitized and doubly eclectic. It marked the beginning of several collaborations with K Records founder and Indie superhero, Calvin Johnson. Steve Albini, Dan the Automator, Alec Empire and others also produced tracks. The cumulative effect was still quite interesting, but the increased role of electronics came at the expense of the rhythm and the blues. The Blues Explosion was always something of a collage. But, by the end of the 90s, they were like collage on top of collage; or a deconstruction of the deconstruction. It became harder to follow their through line.

By the new millennium, after The Strokes, Interpol, The Yeah Yeah Yeahs and LCD Soundsystem had arrived, the Blues Explosion both receded into the background of conversation and graduated to elder statesmen status. They released “Plastic Fang” in 2002 and “Damage” in 2004. The former was largely ignored or disdained by critics while the latter suffered again from an overabundance of producers and a dearth of form. Spencer turned forty in 2005. He and his wife, Cristina Martinez, had been married since 1989. They had a son. Meanwhile, JSBX was increasingly more work than it was benefit. In spite of the band’s name, it was functionally a democracy and it seemed like legislation was harder and harder to pass. There were whispers about Judah Bauer’s health. All the men in the band had side projects that they loved while The Blues Explosion operated as the mothership that paid the bills. However, in the blink of an eye, before the viability of streaming services and after the arrival of the arrival of The White Stripes, the economics turned on JSBX. By 2005, their commercial prospects seemed rather dim. Musically, it sounded like they’d run their course. To me, it appeared that they had run well beyond the finish line. And so, that year, the Blues Explosion began an extended sabbatical that was only interrupted for occasional “money shows,” compilation albums and expanded reissues.

Over the next several years, I barely thought about Jon Spencer or The Blues Explosion. It’s amazing to write that sentence about a person whom I was so enamored of and a band that I so dutifully followed. But it’s true. After 2005, they barely crossed my mind. That is, until one day in 2007 or 2008 when I saw Jon, Cristina and their son at a craft fair in Brooklyn. I did a double take when the handsome family passed me by before I realized who they were. I made a comment to my wife about how I once saw Pussy Galore live and about how amazing the Blues Explosion were in concert. My wife made a comment about how badass Cristina looked. It was a fun, barely memorable, passing moment. Then, we probably bought some bougie houseware for our bougie apartment and I did not really consider Jon Spencer or his most famous band again for a good, long while. That’s what the airbrushed underside of gentrification looks like in the twenty-first century: passing Jon Spencer and Cristina Martinez at the Brooklyn Craft Riot.

Whether it was for love or for money I’ll never know, but at some point around 2010, Jon, Judah and Russell decided to make a go at things again. In 2012 they released “Meat + Bone.” Then, in 2015 they put out “Freedom Tower - No Wave Dance Party 2015.” And, a few years later, they called it quits, again. This time, it had the sound of permanence. But also, nothing stays buried anymore. If there’s some interest or if there’s good money in it, nostalgia digs its way beneath the dirt and the crypt and through the grime and into bones. When those second act albums came out, I did not hear a lot of fanfare. It seemed to me that most of the fans and critics had, like me, forgotten how important JSBX briefly was. I suspect the band was well compensated for a bunch of festival gigs. But I never saw them again, after 1995. Something about that didn’t sit right with me -- that I’d let them go so easily. It felt treacherous. Plus, the few reviews I could find about their final albums were uniformly positive. A couple were gushing. In describing “Meat + Bone,” Jon likened the recording to revving up the engine in a great, old muscle car. I’m not a car guy, but I have to admit that the metaphor worked on me. I wanted to know if the engine turned over. And, of course, what it sounded like.

Released in 2012, eight years after their last studio album, “Meat + Bone” is a sonic reset. True to its title, there’s nothing fancy about it. It’s lean compared to peak Blues Explosion, but fuller in comparison to where the band started out from. If 1994 Jon Spencer was suppressing his inner Jagger in favor of Elvis or James Brown, 2012 Spencer is channeling David Johansen taking on Jagger. In fact, “Meat + Bone” sounds a good deal like the second New York Dolls record or Iggy & The Stooges “Raw Power. But whereas those 70s bands were uninterested in Rockabilly, JSBX is proud of their Crypt Records heritage. Nearing fifty years old, Spencer and his bandmates do not resemble Pussy Galore. They look tired, but determined. And there’s nothing conceptual about this version of the group. Albini didn’t engineer this record, but it sounds like he could have — just three guys, in a room, ripping shit up. In that way, the “Meat + Bone” sounds like their debut. However, the songs are longer, better formed and more concerned with middle-aged things like kids, aging and death. There’s a carnal lust song, that’s also about true love. There’s an instrumental about a guitar and its tone. But there are no songs about “the blues.” There’s nothing about how hard working the band is. There’s nothing remixed by Calvin Johnson or Dan the Automator. There’s two guitars, a drum kit, some keys, scrap metal and theremin. Ladies and gentlemen -- that’s The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion.

Through the first three songs, “Meat + Bone” sets an impossible pace. “Black Mold” and then “Bag of Bones” establish that this is a search for rebirth in the decay. The album isn’t obsessed with rot. It’s not grimey like Pussy Galore. But it is absolutely interested in decomposition -- personal and political. Track three, “Boot Cut,” is a direct response to their beloved “Bellbottoms” from “Orange,” but played more straight-faced. Taken together, the first three tracks have Rock and Roll hooks played with Hardcore’s speed. The leads are bluesy and bent in that Johnny Thunders way, but they’re not broken or buried in that Royal Trux way.

“Get Your Pants Off,” “Strange Baby” and “Unclear” are all noble, if broke down, takes on 60s R&B. The former reimagines the Blues Explosion as The Bar-Kays or Archie Bell and The Drells. It’s got a funky guitar lead and the guys shouting out from the back. It makes you want to clap your hands and move your feet. “Strange Baby” is Jon licking his lips in the general direction of Cristina. And “Unclear” is a slower, winding number that was born from the second half of “Sticky Fingers.” These performances split the difference between early JSBX and the post-Orange version of the band. The songs are cogent and frenetic, but they mostly steer clear of heavy snark and pretense. In 1992 they might have been accused of insincerity. But in the post-White Stripes-and-Black-Keys universe, “Meat + Bone” sounds positively earnest.

Because middle-aged Blues Explosion is less interested in art and irony, there is something surprisingly professional about it. The sobriety with which they go about their work is familiar to anyone who saw them live. But it’s almost radical in comparison to their most famous albums. With professionalism, we get a high degree of quality control. There’s no stinker on the album. The experiments are properly measured. The engine runs just fine. But, also, there are no revelations here. Nothing that takes your breath away like “Brenda” or “History of Sex” or “2Kindsa Love.” In fact, the best track on the album may be “Danger,” which is, ironically, the most basic and sound structurally. Two and half chords played ultra fast on a rhythm guitar that sounds like a lawnmower, plus some broken piano and drums. Verse, verse, short chorus, verse, verse, short chorus. And they’re out in less than three minutes. They sound every bit like The Oblivions covering The Dolls, shouting out a slew of warnings and dead serious commitments:

I got a big amp going off like an alarm

Play licks on my guitar like an atomic bomb

I said, come on police, you can call the law

I don't give a fuck, you can call your mom

Having now spent a couple weeks with “Meat + Bone,” I can say that I really dig it. I like knowing that it exists. It sounds like three guys going back to their practice space on Ludlow Street twenty years later, realizing that now it’s a boutique hotel, but then closing their eyes and remembering the joy and abandon of being young and reckless in an old rotting building but thinking nothing of the decay. Everything decays. But, what a moment Jon Spencer and his band had before the cranes and new construction arrived.

More recently, at least according to Hudson Valley One, Jon and Cristina left the city for a life closer to nature, in Kingston, New York. The local paper was struggling to explain the cognitive dissonance of their new residents alongside the sonic dissonance of their longstanding band, Boss Hog. As of 2019, their son was in college aged and, by all appearances, the gentrification of Jon Spencer was complete. It was well deserved and hard earned. It was grimey and sweaty and glistening.