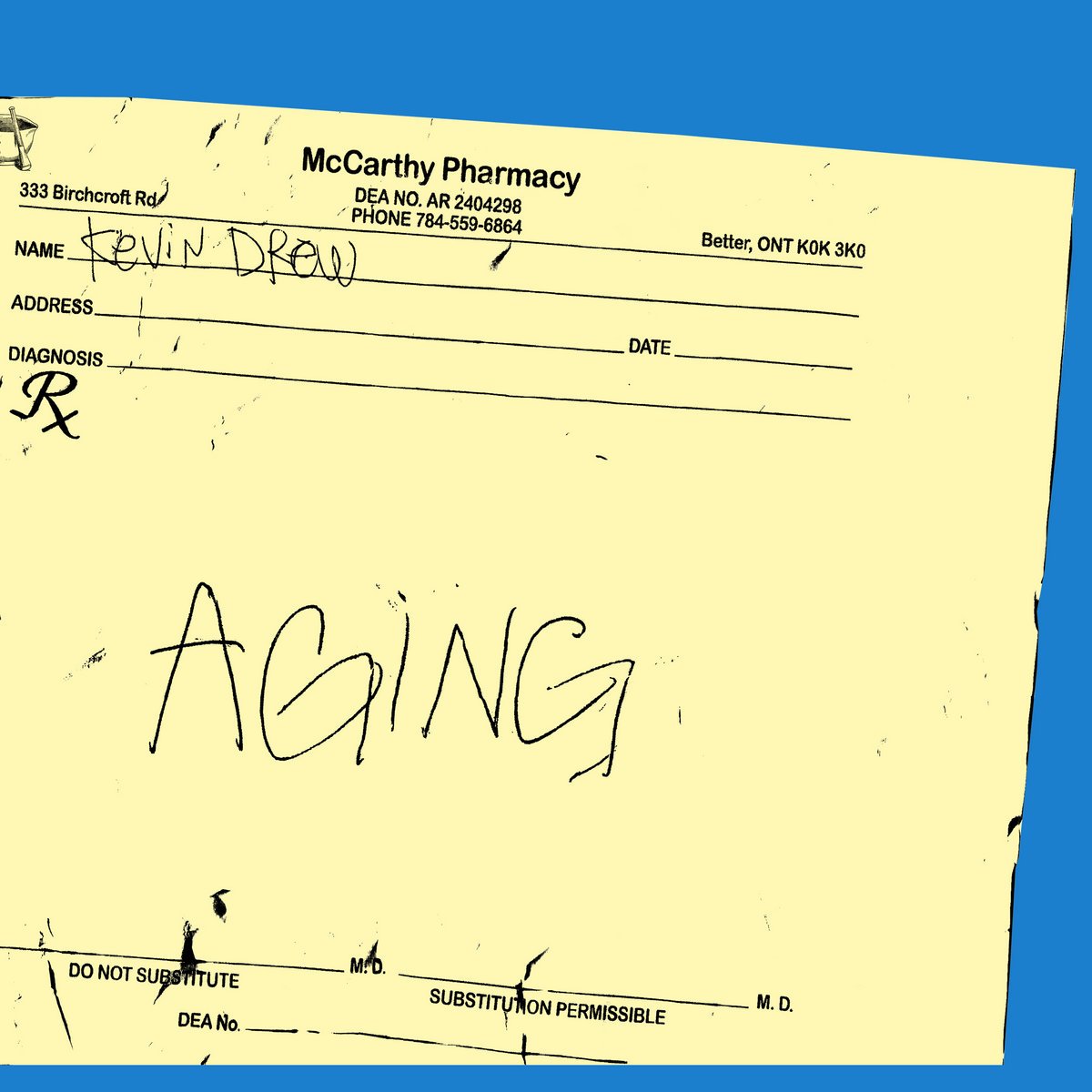

Kevin Drew “Aging”

In the same way that the hive is smarter than the mind and the team is mightier than the player, the Rock band is greater than the Rock star. And before you protest, let me submit the exceptions that prove the rule. Dylan’s best work was always with his greatest bands, including — and especially — The Band. Aretha had The Muscle Shoals all-stars. Prince had The Revolution and The Time. Bruce had The E. Street Band. These were solo artists in name only.

As for those legendary “one man band albums,” McCartney’s solo debut — likable as it is — pales in comparison to everything he did with Wings, not to mention that other band he was in. Rundgren’s “Something/Anything?” is more impressive than timeless. Even Jeff Mangum had some buddies stop by to play horns and saw on “In The Aeroplane Over the Sea.” In fact, in the whole history of Rock and Roll — using the term loosely but no so broadly as to include electronic music — I can think of only one really, truly solo masterpiece — one record made by one person that survives as the greatest work of a great artist: “For Emma, Forever Ago,” by Bon Iver. That’s it. Everything else confirms the obvious: there’s strength in numbers.

Yes, it’s hard to be alone. Which is why, once upon a time, Kevin Drew found himself a partner. Lacking the virtuosity of Prince or Rundgren, and more interested in Art Rock than Just Rock, he started off as one half of duos. First, with Charles Spearin in KC Accidental, and then, more famously, with Brendan Canning in Broken Social Scene. However, a couple years and one record into BSS, Drew discovered a corollary to the strength in numbers theory. He realized that duos are also a problem. That, in Rock and Roll, two is not really an even number. Duos wind up less a partnership of equals and more an uneasy arrangement. Hall & Oates. The Carpenters. The White Stripes. Ike & Tina. There’s no third in the relationship — no one to break ties or shake things up. There’s not enough oxygen in the room. But moreover, there aren’t enough good ideas. Duos are inevitably doomed by their imbalance of power or forced evolve into something else — something like a band.

And that’s what happened with Broken Social Scene. Kind of. Before Broken Social Scene there had certainly been big Rock bands. Sly and the Family Stone. Chicago. Santana. And there had been groups which featured rotating casts of players. King Crimson. Fleetwood Mac. Steely Dan. But Broken Social Scene was different in that they were more voluminous and more diffuse than their predecessors. They were formed by Drew and Canning but were not designed around any one star, or two stars, or even a core. They gathered around a sound, an idea and — most of all — a city. They were all friends from Toronto — sometimes more than just friends. Over the course of one year, Broken Social Scene went from interesting duo to mind blowing amoeba.

If they looked like an amoeba, Broken Social Scene sounded like a bonfire. Any time they smoldered — someone else would show up and throw a log on. What had started out as a partnership between two friends became a massive, shapeshifting organism of platonic and not platonic neighbors. Their spell was in part the wall of sound — grand and messy at times, hushed and intimate elsewhere. Constantly on the verge of collapse, but more so on the brink of revelation. Their magic was not in Drew or Canning’s compositions but in the ways friends changed those compositions. Or, in the case of “Almost Crimes” and “Anthems for a Seventeen Year Old Girl,” the way friends swallowed those compositions.

Lesley Feist and Emily Haines were not founders of Broken Social Scene. In fact, true to the band’s raison d'être, they are not even permanent members. Most of the songs on “You Forgot It in People” do not feature them at all. But when they appear, the record leaps from compelling to spellbinding. From awesome to holy shit. Broken Social Scene’s now legendary sophomore album is a testament to the hive over the bee. To chaos that finds its own order. It was the album that validated Pitchfork’s weight in the Indie hegemony. The record that turned Lesley Feist into, simply, Feist. The music that a generation fell in love to, fucked with, and had their hearts broken to. It would not have existed without Radiohead and Godspeed You! Black Emperor. But, also, it spawned The National and Arcade Fire. It is, without question, Kevin Drew’s crowning artistic achievement.

Yes, he made two albums with KC Accidental. Yes, he made four other albums with Broken Social Scene and four records under his own name. But “You Forgot It in People” is the one. Which is an odd thing to say because it is also an album wherein Drew disappears for long stretches. He is everywhere on the record, and yet, it’s everyone and everything else that stands out. The other vocalists. The horns. The bass. Drew might be half bandleader. He might be fifty percent conductor. But it’s hard to tell because hands are never too heavy. His voice never too loud. He’s the glue guy. The vibes guy. He’s shining the spotlight elsewhere, all the time. All the time, except one time. “Lover’s Spit.”

“Lover’s Spit” is Drew’s magnum opus from his crowning achievement — a gorgeous, plaintive ballad in the vein of Procol Harum’s “Whiter Shade of Pale.” It’s the sort of song that you never want to end — that you want to die slow dancing to. It has rightfully soundtracked many movie scenes, to the point where it has come to signify “Early Aughts Hipster Romance.” But no matter how cliched or overplayed, it does not matter. “Lover's Spit” is perfect. It’s Kevin Drew singing on Kevin Drew’s song. It’s so good that even the alternate version, which is breathtaking and features Feist on lead vocals, mostly serves to remind us that the song was meant to be sung by Kevin Drew.

Because Broken Social Scene — as we all think of them — never really formed, they also can never really break up. But because they are a collective, united by shared spirit and citizenship more than firm commitments, they also are not a full time concern. As a result, Drew has an unusual relationship to his own music and celebrity. He is more than semi-famous, but certainly not famous. And he is known mostly on account of a band that he co-founded but disappears into. He is less famous than both Lesley Feist and Emily Haynes, whose work is generally beloved but not the way “You Forgot It in People” is obsessed over. And, “Lover’s Spit” notwithstanding, there’s scant evidence that Drew he is a superb singer. He has a knack for melody but he seems to prefer noise. He’s an extrovert who’s adept at hiding away. Everyone seems to love Kevin Drew. Hell — Meryl Streep joined him on stage that one time. But, best I can tell, nobody can explain exactly what it is that he does.

Every BSS album since “You Forgot It in People” has been an event. The reveal of who’s in and who’s out. The excitement of a possible tour. And the inevitable comparisons to their masterpiece. But. while they have all been events, they have been more so celebrations. For all of the gothic romance of “Lover’s Spit,” or the abstract doom of “Shampoo Suicide” or “Sweetest Kill,” Kevin Drew sure seems like a jubilant fellow. He’s the guy who had the idea for the bonfire in the first place. He’s the first one to start singing. His brand is “Hug of Thunder.”

But he’s also a guy who exists outside the collective. In between those BSS records, Drew has been releasing lower stakes solo albums. Initially, with many members of Broken Social Scene. Then with a few. And then, finally, all alone. Drew, just like the rest of us, spent long stretches of 2020 isolated. And, just like us, he lost. He lost time. He lost friends. But most of all, he lost his mom. Not to COVID. And not suddenly. Piece by piece. It was all sadly, terribly, relatable. With one exception — we weren’t also founders of a band that was actually a collective that was actually a friendship gang. We weren’t so publicly, irrepressibly likable and convivial as Kevin Drew. Which is why, late in 2023, when Broken Social Scene’s co-captain released “Aging,” it was the opposite of the hug of thunder. It was a request to be held.

“Aging” was an accident begot by tragedy. It began, without a title, as Drew’s attempt to make music for children. But the more time he spent with the idea, and particularly the more time he spent with “Don’t Be Afraid of The Dark,” the more he realized that — like all lullabies — his songs were about death and loss as much as they were about love and life. And so, through the pandemic — through the loss of his friend and mentor, Hal Wilner, and the deterioration of his mother — that album for children became an album for aging children.

Even still, “Aging” is barely an album. Just eight tracks. Thirty minutes. By BSS standards, it’s an EP. But, to hear Kevin Drew tell it, this was the most important statement of his career. Much of “Aging” could be reasonably mistaken for mid-Aughts practice sessions by The National — a band who owes more than a little to BSS — or Radiohead — the band who BSS owes more than a little to. Piano is frequently the lead — heavy, tonal and dark. Most, but not all, of the rhythms are electronically programmed — like pulses more than beats. And there are thin layers of synthesized noise everywhere. Sometimes those synths sound like strings. Sometimes like storms or wind. There’s absolutely guitar and bass on the album, but they recede into the weight of everything else. Whatever you’re hearing as you read this is probably not so far off.

As for the “weight of everything else,” I mostly mean anxiety, depression, longing and — graciously — self-acceptance. “Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark,” is the closest the album gets to children’s music, and is also the most obvious outlier. The vocals are auto-tuned, pitched up an octave as if to suggest both Drew and Drew’s mother. It’s an unusual, but not odd, effect. I think it works. Minimally, it succeeds in unsettling us. In reminding us that the most frightening thing about nighttime is not the dark or the bad dreams, but the thin line between sleep and death.

On an album that ranges from dark to funereal, “Elevators” is closer to the former, kicking off the album with a rumble — a piano seemingly borrowed from The Natonal’s “Boxer” and left untuned since. The rhythm — a quickening thud rather than a steady (or unsteady) pace — builds and builds. The elevator is coming. No matter whether he’s pushed the button or not. Whether he wants to get on it or not, Drew realizes that the elevator is coming. For his loved ones. For him. For everyone.

“Awful Lightning” paints with the same palette. Lonely piano. Big room. Heavy hands. Heavier heart. If you swapped Drew for Matt Berninger, it would pass for an old National B-side. But this time, and unlike “Elevators,” the singer isn’t waiting for the call — he’s asking for it. His body aches. He’s slow and tired. He’s had enough. The synths sound like cellos which also sound like drama. The tension builds. It’s not a matter of if the awful lightning will strike, it’s just a matter of when.

Elsewhere, there is plenty of mood, but less of the tension. “Party Oven” almost, kind of, nearly suggests “Lover’s Spit,” but then trudges into the opposite of romance — which is not divorce or tragedy, but dullness. The questions it poses are interesting enough. It wonders about the difference between a life well lived and a life well avoided. About whether the partying is the point of it all or completely meaningless. But it’s a lackluster song. Flat melody. No drama. While depression is obviously a worthwhile subject in art, it presents formal challenges in Pop or — in this case — Semi-Pop music. A lot of “Aging” sounds depressed. Not hollow, but definitely hollowed out. Drew has no one else around. No one to throw a log on the fire. No Feist of Emily Haines to cut through the beautiful mess. And so we are left with a lonely album, made by a lone man, consumed with loss. If we were to grade albums on the basis of honesty, “Aging” would rate highly. But if we listen for pleasure or almost any other value aside from honesty, it’s a much tougher sell.

Part of the challenge of “Aging” goes back to the problem of the solo artist. Too much of one thing and not enough of everything else. But, my ambivalence is also — and probably more so — specific to this particular artist. Kevin Drew is not Justin Vernon or Elliott Smith or Nick Drake. We fell for him because he was not a man alone with his thoughts. Because he made space for everyone else. If Broken Social Scene was the promise, “Aging” is the breach. I understand why this record needed to be made — truly. For whatever it lacks in pleasure, it possesses truth and virtue. And for whatever critical fate Drew suffered — a handful of middling reviews and a whole lot of indifference — I suspect that he also received a bunch of thunderous hugs.