Lyle Lovett “Release Me”

Has there ever been someone so completely reliable as Lyle Lovett who looked so completely dodgy as Lyle Lovett? The man in asymmetrical. One of his eyebrows is perpetually raised while the other sits still. His mouth turns down in one corner while the other side purses. His nose is way too big for his eyes. When he smiles, it looks like he’s in pain. And don’t even get me started with the hair -- it does whatever the fuck it wants. He’s about six feet tall and I bet he’s never seen one hundred and fifty pounds on a scale. I recognize that I’m venturing into the realm of body shaming here, but — really — on the most superficial level, Lyle Lovett does not look like a guy you can trust.

And yet, he’s always in a tasteful blazer with a tasteful shirt and collar. Sometimes there’s a pocket square, but there is always a please, a thank you, a sir and a ma’am. While he might appear as atypical as Joey Ramone, he sings like he’s Jackson Browne. And he’s spent most of his lifetime flanked by beautiful women, who are seemingly enthralled by every single thing about him. Sure -- the world was shocked when he and Julia Roberts ran off and got married. But, the incongruity of the couple was quickly subsumed by a second narrative: Lyle Lovett had it. Whatever “it” implied, Lovett possessed it. And so, after he and Julia split, when he was spotted with the equally lovely and talented Kelly Willis, no one flinched. In fact, soon thereafter, when a seventeen year old Connecticut cheerleader left home to move in with the nearly forty year old Lovett, it barely made the news. By the 1990s, it was settled fact, Lyle Lovett was the opposite of dodgy.

The evidence for this claim is overwhelming. There are the piles of four star reviews. There are the six straight Gold (not Platinum, because that would be too showy) albums. There are the four Grammy wins. There’s the fact that, in films, his songs signify “romantic comedy,” assuring us that smiles are on the other side of the conflict. There’s the theory that the universe had to invent both Chris Isaak and Bob Schneider to create more sex-forward Lyle Lovett product. There’s every humble and mannered interview he’s ever done. There’s the fact that he lives in the same house that his grandparents built over a hundred years ago. And there’s the fact that, whether he’s singing Folk music, or Country or the Blues or Big Band Jazz or Americana, he almost always sounds exactly the same. Yes -- Lyle Lovett sure is reliable.

As for what, exactly, we are relying on him for — well, that’s the question. Right? Vocally, it’s his warm, laconic delivery. Never too high or too low. Musically, it may be how his dials are always set between four and seven. He’ll occasionally get quiet, but never veer into Nick Drake territory. And while he can rock and roll, even his “Large Band” would never be confused for The Rolling Stones. His songs are equally suited for small dinner parties in Brooklyn and old Sandra Bullock movies in Anytown, USA.

And this is not to even mention the Texas of it all. Perhaps more than anything else, Lyle Lovett signifies “bougie Texan.” He’s not a hippie like Willie. He’s not a cowboy like Waylon. And he’s not rich like J.R. Ewing. He’s a Texas A&M Aggie, from the Houston area, with two degrees, who is equally beloved by Longhorn fans from Austin. He’s a cattle rancher and a motorcycle racer. His politics are clearly left, but there’s a prideful, libertarian not too far below his surface. Just after “Outlaw Country,” but before “Alternative Country,” we got Lyle Lovett. And though historians might compare him to Nanci Griffith or Robert Earl Keen or James McMurtry, the truth is that no artist before or since made the big leap from Texas Tea to Sonoma Pinot so effortlessly.

Many years after his breakthrough, after Julia and after he was mauled by a bull on his farm in Texas, when he was out of the spotlight, Lyle Lovett was still completely trustable. Every three years or so, he’d deliver a very good to great album. Sold out theaters and amphitheaters were filled with loud, but courteous, applause for every show of every tour. Occasionally, The New York Times or Texas Monthly would do a profile to remind us about how great he was — about how lovely his songs were and about how sincerely he honored the tradition of Townes Van Zandt and John Prine. About how his new album was different from the old ones, but also how they were kind of the same. The same voice. The same warmth, the same knack for storytelling and the same, sneaky dark humor. In middle age, Lovett had become something of an institution, the Texan who nudged Folk Music and Country Music ever so slightly closer to Jazz and Rhythm and Blues.

He was so reliable -- so upright -- that when his contract with Curb Records, which had spanned nearly three decades, came to an end, they trusted him to break up gracefully. In the preceding years, the label had instituted a policy that effectively forced artists to release albums less frequently, so that marketing resources might stretch further across the roster. It might have been a reasonable, even necessary, business decision. But Lovett did not appreciate the approach. And so, he let it be known that his eleventh album for Curb would be his last. In the music industry, there is a term for the final record that is reluctantly owed to the company who signed the artist before s/he had leverage. It’s called the “contractual obligation album.”

The most famous, and hilarious, contractual obligation album may be the one Van Morrison delivered to Bang Records in 1967. Thirty one tracks. None more than one hundred seconds long. Many under a minute. Track eighteen was called “Blow in Your Nose,” which was followed by “Nose in Your Blow.” Though possibly heroic, it might also be the pettiest act in the long career of a great artist known for his pettiness. Lou Reed tried, unsuccessfully, to escape his contract with RCA in 1975 with the infamous “Metal Machine Music.” In 1982, Todd Rundren marked the end of his time on Bearsville Records with “The Ever Popular Tortured Artist Effect.” And, in 1980, the Monty Python crew literally released “Monty Python's Contractual Obligation Album.” The list of requisite, but embittered, final albums is long and varied. But they all share a couple of things in common: First, they are disgruntled. And second, they are either terrible or completely lackluster.

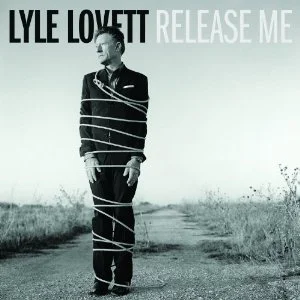

In spite of this long history and Lovett’s public consternation with Curb, he was given a curiously wide berth. Whether out of reverence or legal maneuvering, he was allowed him to make exactly the record he wanted to make. He chose to call the album “Release Me.” No thin veil there. But, also, no problem. The album’s cover features the singer literally tied up in rope, trapped on a country road. Not the subtlest of symbols. But, Curb still gave him the green light. Of the fourteen tracks on the album, only three are written by Lovett, two are holiday tunes (on an album released in February), two others are traditional songs and one is a cover of a Lutheran hymn.

In spite of all signs pointing to the middle finger, though, Curb allowed Lovett to release an album that seemed both displeased and perfunctory. Why? Because Lyle Lovett is the guy you can trust. And you know what? Curb was right. Even though he felt somewhat aggrieved and even though he was aching to move on from his record company, Lovett simply could not not be trusted. “Release Me” is not a steaming pile of shit on the doorstep of Curb Records HQ. To the contrary, it’s a mostly lovely, charming, if unnecessary, collection of excellent songs and dependable performances.

“Release Me” would not crack any top ten (of twelve total) list of Lyle Lovett albums. But that is not to suggest that it is terrible, so much as it is inessential. On the other hand, age does provide some benefits. A quarter century after his debut, the singer songwriter is assured and polished in a way that young “folkie Lyle” could not have been. Additionally, if the song selection came from the bottom of the barrel, that barrel is richer and smokier than what it was in the beginning of his career. Every genre that Lovett has toiled with, save for Jazz, is represented. If “Release Me” really is Lovett’s trash, it’s as though he’s lovingly curated it -- removing anything rotten or broken -- so that what remains is eminently pleasing for the guys at the dump.

As one might expect, there is no narrative arc or abiding theme to this album. It’s simply the best of the leftovers. But as with day old New York pizza or Chinese food, some of these scraps are wonderful. The best two songs are covers that would fare admirably on the best Lovett albums. The title track is a gorgeous take on a song that Ray Price made famous in the 1950s. Lovett elects for a spare, hopalong beat and the slightest backing necessary so that his words, delivered alongside k.d. lang, get all the oxygen they require. “Release Me” is a gutting plea for freedom to a would be ex. Given the context, he could have played it dry, for snark. But he and lang simply cannot not locate the tragedy of the song. Lovett is plain, but honest. Lang is pained, and true.

The second cover to land is “Understand You,” originally written by his buddy Eric Taylor, who is also the former Mr. Nanci Griffith. Rendered as a very slightly Country Folk song that is also a naked love song, it’s a wonder that this one didn’t make its way onto any previous Lovett album. Unlike most Country romances, which rely on heartache, betrayal or cliche, this one carries the weight of real honesty. Lovett sings from the aftermath of some argument or breakdown in communication and, instead of pointing fingers or begging for forgiveness, he pleads for understanding. He doesn’t want to “win.” He doesn’t need to be right. Or sorry, even. He wants to know who she is and what she means. And you believe every word of it.

There are also much more famous, though perhaps less successful, covers on “Release Me.” “Baby It’s Cold Outside” is obviously unnecessary and possibly problematic, except for the fact that Lovett’s duet partner, Kat Edmonson, was born to sing the song. It’s a darling version of the holiday classic. More surprising is his take on Chuck Berry’s “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” which Lovett renders as a Folk song about equity, highlighting the greater subtext of a song that I, for one, had underestimated.

All three of the Lovett originals appear on the back half of the album, as though they are hiding or buried. They are minor additions to his songbook -- a couple of pleasant oddities and one piece of unfinished business. The two curiosities include a loose, bluesy number about a sex worker with a glittering smile ("The Girl with the Holiday Smile") and a sweet, countrified lullaby alongside fiddler, Sara Watkins, and her musical brother, Sean ("Night's Lullaby"). Both are perfectly adequate songs, performed gracefully. Nothing more. The other original, “One Way Gal,” is also predictably charming, but completely inessential. It’s a tired Blues progression, paired with exactly ten sentences, five of which are repeated to create the (five) verses. With Lovett, there can be a fine line between “easy” and “easy going.” This one leans towards the former, on the just on the right side of “lazy.”

While he had previously shown an affection for Gospel music, it’s not the most natural fit for Lovett’s style or his voice. And, unfortunately “Isn’t That So,” only serves to confirm the mismatch. Two soulful tenors, a horn section and some nifty blues are not enough to push Lyle’s range or his pace on the Jesse Winchester tune. And on the album’s closer, Lovett goes back to the well of holy water. “Keep Us Steadfast,” a hymn attributed to Martin Luther, is played mostly straight — just piano, a bass set back, and some strings. It’s not much more than a dirge with just enough space for a glimmer of hope. It’s somewhat affecting, but also the sort of thing that inspires a “hmm” and then a shrug. In fact, that would not be an unfair review of “Release Me".” Hmm. Shrug. It’s better than that. But still.

Following “Release Me,” Lovett did not make any new music for a decade — by far the longest stretch of his career and surprising for a man who was hell bent on liberation. In between, however, he married April Kimble, who he’d been dating for twenty years. And that same year, he became a father of twins. Even at sixty, he was sensible and trustworthy. But, also, still capable of surprises.

When I first heard Lyle Lovett many years ago, I was living in New York and understood him to be something of a novelty -- a well-dressed take on a Texas rancher who went to Austin and got big ideas. Living in the northeast, he was the perfect cusp outsider. He looked and sounded different from anyone I knew, but was also a musical bridge between real Texas, bougie Texas and cocktail parties in Westchester. Today, however, I live in Texas, among Aggies and Longhorns. And while I still enjoy Lyle Lovett’s music and appreciate his special charm, I look to him for something more: hope.

In 2022, Texas can sometimes feel like ground zero for late capitalism or like a crucible for democracy itself. It can be hard to trust anything — good or bad — that is happening in my new(ish) home state. So, on my most cynical days, I opt to think about Lyle Lovett. He’s the best of Texas. And he did it. He reminded those of us on the coast that Townes Van Zandt’s Texas was also LBJ’s Texas which was also, simply, Texas. At the same time, he put on tailored suits and went to Hollywood and made Folk music which proved that Country was literally just a Swing away from Jazz. He did that in spite of the hair and the eyebrow thing and the downturned mouth. Or maybe because of. And so, to me, Lovett is probably even more essential than ever. I just only hope he’s as reliable.