Bon Iver “Sable”

As Bon Iver evolved from loner in the shack to experimental Jam band, Justin Vernon became more diffuse — and more opaque. His voice was everywhere, but his songs were impossible to decipher. His career was simultaneously safe and unpredictable. He was Indie Rock canon verging on Pop canon, but one never knew when or if the next album would come. And one never knew what it might sound like — except that it wouldn’t sound like “For Emma, Forever Ago.” Justin Vernon was not going back.

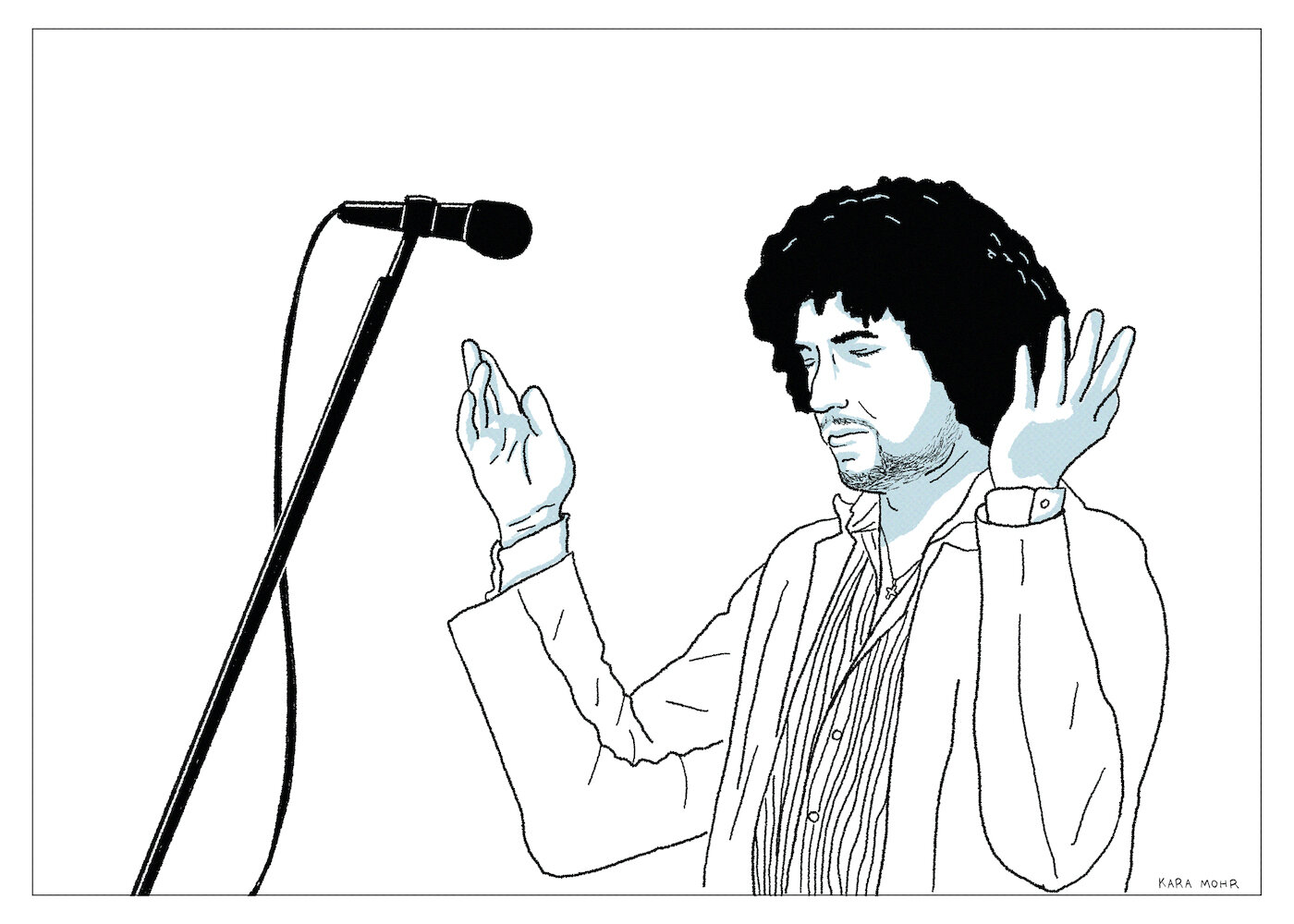

Bob Dylan “Together Through Life”

If Past Past Prime Van Morrison sounds like disgruntled Soul, and if Past Past Prime Leonard Cohen sounds like breathy Tao, Past Past Prime Dylan sounds more like Willie Nelson. It’s the sound of an artist working tirelessly, but with an air of retirement. The stakes are lower. There’s nothing to prove. And even if he had an agenda it would be swallowed up by his voice. That voice. The voice of relief and release. The voice of self-knowledge and self-acceptance. If you squint your ears, those post-”Time Out of Mind” records — from “Love and Theft” through “Tempest” — sort of blend together. The bands vary. Stories and settings change. But they share a common pace, range and — most of all — voice.

Los Lobos “Native Sons”

Over the course of nearly fifty years and seventeen studio albums, Los Lobos have been many things. A wedding band. A Rock band. A Folk band. A Punk band. They’re omnivores — multi-instrumentalists, songwriters, radical interpreters and loyal cover artists. Their influences are as diverse as their influence — members of the band have appeared on records from pretty much every legend who's passed through Los Angeles since 1980. From Bob Dylan to Eric Clapton and from Dolly Parton to Bonnie Raitt. Like their hometown, Los Lobos are diffuse. And like their hometown, they are Mexican. Which is why, more than anything, Los Lobos are underestimated. Pop music comes in many forms, but it gravitates to the specific and the English. Meanwhile, Los Lobos’ greatness lies in the fact that they are almost the complete opposite of those things.

John Denver “It’s About Time”

Even before his divorce from Annie Martell, before the death of his father, and before his star had fully faded, John Denver’s music had begun to take a detour. At first, the turn was slow and gradual enough to be barely noticeable. But, by the early Eighties, he’d largely abandoned the acoustic jangle of his Folk and Country hits for something firmly Adult Contemporary. And by “Adult” I really mean something like music for children performed with a string section, and guitars and synths turned down so as not to disturb. And by “Contemporary” I really mean corny like late Seventies Margaritaville James Taylor or like Barry Manilow without the camp. That’s the sound of “It’s About Time,” an album of depressed ballads and worldly aspirations performed by one of the most overqualified bands ever assembled.

Gordon Lightfoot “Shadows”

To the cynical or the uninitiated, “Shadows” can sound like a Will Ferrell spoof — like music for lovers who refer to each other as “lover.” Like music to be played while wearing cable knit sweaters, sitting by the fire and sipping Canadian Club. But for those who either know Lightfoot’s oeuvre or who are familiar with Seventies Adult Contemporary Rock music, the sound is not unfamiliar. On top of twelve string acoustic guitar, delicate windchimes and lite violins, Gord’s boozy baritone narrates a slideshow about middle-aged resignation and that trip to the Bermuda Triangle. Released the same year as The Clash’s “Combat Rock,” Duran Duran’s “Rio” and Culture Club’s “Kissing to Be Clever,” “Shadows” was miles from anything hip or New Wave. It was the sound of a guy singing to himself, because he had to, because he was tired and lost and the world had moved on. It was the end of the line for Gord’s minor Pop stardom, the beginning of his sober second half and the most interesting album he made after “Sundown.”

Marah “Marah Presents Mountain Minstrelsy of Pennsylvania”

The first wave of Dad Rock is canon — Dylan, The Band, Petty, The Boss. Occasionally, it veers into Indie or Alternative Rock (REM, The Replacements) or headier stuff (The Dead, Steely Dan). But, broadly speaking, it’s American Roots Rock for educated men who are older than thirty but younger than sixty, who are likely to drink craft beers and who desperately want their children to understand the glory of “Jungleland.” The second wave of Dad Rock is still a work in progress. In the early Aughts, bands like The Hold Steady and Band of Horses and Arcade Fire began to make their cases. Some of the neo-Dad Rockers were cut from The Boss’ cloth (Gaslight Anthem, The Constantines) and others were perhaps closer to Dylan (Bon Iver, Sufjan Stevens). But the ones who should have been kings — the ones who got it all started but then got lost in the plot — were Marah.

Art Garfunkel “Scissors Cut”

From 1970 through 1973, Art Garfunkel was among the most fascinating men in America. Coming off of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” he turned his attention to acting, where he made his debut in Mike Nichols’ “Catch-22.” The next year, he was nominated for a Golden Globe for “Carnal Knowledge.” Eventually, though, he reemerged as a solo recording artist. “Angel Clare,” from 1973, produced two top forty singles, and a series of Gold and Platinum-selling albums soon followed. What began as warm possibilities, however, devolved into flaccid melodies and artistic stagnation by the end of the decade. And then, tragically, Garfunkel’s romantic partner of many years, Laurie Bird, committed suicide in 1979. Most of America was depressed in 1979, but Art Garfunkel was more depressed. 1981’s “Scissors Cut” is the evidence of that depression — a bawling, private eulogy, pressed onto vinyl. It was also the end of “Art Garfunkel, Pop Star.”

Lyle Lovett “Release Me”

Has there ever been someone so completely reliable as Lyle Lovett who looked so completely dodgy as Lyle Lovett? One of his eyebrows is perpetually raised while the other sits still. His mouth turns down in one corner while the other side purses. When he smiles, it looks like he’s in pain. And don’t even get me started with the hair. On the most superficial level, he does not look like a guy you can trust. And yet, by the 1990s, it was settled fact: Lyle Lovett is completely trustworthy. See the piles of four star reviews. The six straight Gold (not Platinum, because that would be too showy) albums. The four Grammy wins. And the fact that, in 2012, when he was making his “contractual obligation album” — the thing that is supposed to be resentful and perfunctory — he was still impossibly mannered and listenable. Turns out that Lyle Lovett is the exact opposite of dodgy.

John Prine “Lost Dogs and Mixed Blessings”

We all knew he wasn’t going to be the “Next Dylan” (they never are). He wasn’t pretty enough to be Johnny Cougar. And he was too good to simply gut it out on Music Row. But John Prine never really went away. He just sort of stood in place waiting for us to circle back. That happened in 1991 when Petty, Bruce and friends helped celebrate the great comeback of an artist who hadn’t gone missing. Four years, a marriage and two kids later — Prine wondered: where do you go after you’ve just come back?

Bonnie “Prince” Billy “Wolfroy Goes to Town”

In the years after his beloved “I See a Darkness,’ Will Oldham aged comfortably into his Bonnie character. Each year, we would get a new album. We wouldn’t know when it would arrive or what it might sound like, much less what it meant. But it would come. And it would generally be excellent. And then something similar, but different, would happen the next year. Behind Oldham’s warble there was Cheyenne Mize. Then, Ashley Webber. And then, in 2011, on “Wolfroy Goes to Town,” it was the great Angel Olsen.

(Yusuf) Cat Stevens “The Laughing Apple”

There has never been another Pop star who went away for twenty eight years and then returned. Obviously, Cat Stevens didn’t really go away. During his absence from popular music, Yusuf Islam was always looking for that road back. And, in 2016, he found the bridge. He reunited with his closest 1970s collaborators and announced that he would release a new album under the name “Yusuf / Cat Stevens.” As hedged as it looks on the page, it was received as a full throated return for his long suffering fans.

Donovan “Sutras”

After the 1970s, Donovan was no longer a “popular” recording artist. He had no discernible fanbase, no radio airplay and no American record label. Between 1984 and 1996, Donovan released no new music. While he was not making music, though, he continued to do something he had been doing for decades. He meditated. In the world of music, two of the most visible advocates for T.M. were Leonard Cohen and George Harrison. But a slightly younger and more bearded, Gen X-er has followed in their footsteps. And Rick Rubin promised Donovan the same spare, but royal, treatment that had just worked wonders for Johnny Cash.

Jeff Tweedy “WARM”

Well, he did it. It’s not a perfect record. Far from it. It’s not his best music. No. But I suspect Jeff Tweedy will never get closer to something as honest, as definitive and as unflinchingly empathetic as he does on “WARM.” This is monumental, middle-aged, dude stuff. It is what the other side of decades of therapy sounds like for one of the greatest songwriters of the last thirty years. It’s a search for meaning through empathy and self-acceptance in the second half. If “WARM” were presented to me as the Old Testament for some sort of cultish men’s group, I’m pretty sure I’d sign up.

Stephen Malkmus “Traditional Techniques”

Pavement broke up but Stephen Malkmus kind of stayed the same. He moved to Portland. He got a new band together. Every two to three years he would release an A- album. I listened to some of them. They were uniformly very good to great. It became easy to take Malkmus for granted. There was nothing not to like but it was getting easier to pass over. Surely, Malkmus himself felt some of this. First there was the solo electronic jams on “Groove Denied.” and then came “Traditional Techniques,” wherein Stephen Malkmus daringly and beautifully articulates the search and the journey.

Kris Kristofferson “To The Bone”

By 1981, Kris Kristofferson found himself alone, sad, sober, resentful and pretty much any other cliched adjective you could toss at a broken, divorced, about-to-be has-been. At forty five, with almost nothing to lose, and following a recent trail of mediocre records, he released “To The Bone.” Along with Marvin Gaye’s “Here, My Dear,” “To The Bone” is one of the most candid and compelling “divorce albums” in the Pop music canon.

David Crosby “Oh Yes I Can”

On his first solo album in almost twenty years, Crosby managed to sound quite vital on 1989s “Oh Yes I Can.” “Vital” as in “healthy,” rather than “essential.” There’s a big difference. His life story has been rich and compelling. He has been a cautionary tale and an inspirational voice. But, stripped of the counterculture and of his greatest collaborators, Croz ends up sounding like the guy playing on the small stage at a farmers market.

James Taylor “Never Die Young”

James Taylor is more opaque than Prince or Bob Dylan. Is he the genteel, humanist who invented Adult Contemporary music fifty years ago? Or is he an overly-sensitive, over-valued bar singer who succeeded by virtue of his good looks and birthright? By 1988s “Never Die Young,” Taylor had recently re-married and was still very much in the throes of a fledgling sobriety. It was a miracle he was alive, much less a viable recording artist. If ever there was a time reveal his true self, this was not it.

Leonard Cohen “Various Positions”

In 1984 Leonard Cohen released “Various Positions.” It was his first album to substantially use the Casio keyboard. It is also the first wherein Jennifer Warnes is billed as “co-singer.” At fifty years old, with Cohen’s voice bottoming out, his soul sounded like it was one hundred. Plus, the curious new sound was greeted with cynicism by Cohen’s label. Turns out, the label was wrong. “Various Positions” not only gave us “Hallelujah,” it also crystallized the sound that would become the hallmark of Cohen’s extraordinary third act.

Richard Thompson “Rumor and Sigh”

If there has ever been an artist who completely sustained their prime for an entire career, it is Richard Thompson. His highs are not as high as Dylan’s. And his finest records are not perfect in the way that, say, “Astral Weeks” is. But while his peaks are not as high, his consistency is almost unprecedented. What is the “best” Richard Thompson album? Was it 1974s “I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight”? Was it 1982s “Shoot Out The Lights”? 1999s “Mock Tudor”? Or was it, as many would say, 1991s “Rumor and Sigh”?

Bob Dylan “Shot of Love”

There have been countless revisionist takes on every part of Dylan’s career, including his “born again” phase. So, I guess you can add this to that pile. But, while I don’t feel original, I do feel so lucky that I came to this album without the baggage of trying to unpack in during its original context backlash. Today, it’s nothing short of a gift. Sure, Jesus is there. But, Dylan also conjures Levon Helm, Mavis Staples, Johnny Cash and most of his past lives.