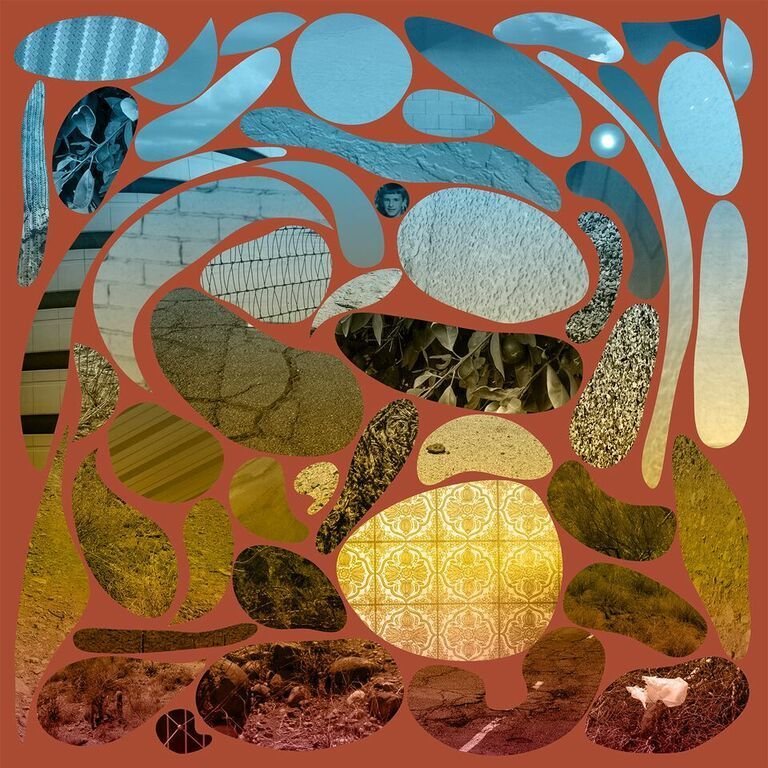

Pedro the Lion “Phoenix”

Unless you’re Carl Jung, or somebody who studies Carl Jung, I suspect that hearing about other people’s dreams is wholly uninteresting. And yet, I simply have to share: For almost twenty five years, I’ve had a recurring dream wherein I find myself in my boyhood home. My family no longer lives there. I’m slightly disoriented by the new decor and completely anxious about my illicit presence. Right before I am discovered, however, I wake up. That sensation of being back home while full well knowing that you can never go back home -- there’s something to it. It’s apparently a very common dream, along with missing your exam at school, losing your teeth and free falling. Mine began in early 1997, around the time that my parents' brittle marriage finally buckled. I was twenty-three at the time and out on my own. It was a year of high hopes, small paychecks and new apartments. It was a year of Radiohead CDs and Yo La Tengo at Tramps and Neutral Milk Hotel at Brownies. It was also the year that I discovered Pedro the Lion.

I’m not even sure why I picked up their CD at Other Music but, decades later, I suspect it has something to do with those dreams. “Whole” was Pedro the Lion’s first record. It was released on Tooth & Nail, the Christian Rock label which had garnered some renown from the success of MXPX, a Pop Punk band who’d crossed over into the mainstream. “Whole’s” album cover was golden tan with an E.B. White-ish illustration of a lion and its shadow. The CD contained just six songs. Barely twenty minutes. I knew nothing about it, really. I’d heard of Tooth & Nail, but that was it. I was Jewish, and not religious. I’d not read any reviews or gotten any tips. But there was something so delightful and simple about that cover and that name. And the fact Other Music stocked it and placed it in the “Indie” section, right after “Pavement”—that was enough for me. I forked over $8.99, which was my dinner budget for the evening, promptly went back home to Brooklyn and pressed play on the darling little record.

While I knew virtually nothing about Pedro the Lion, I sensed almost immediately that they were different. They weren’t cool like Sonic Youth or Pavement or voluminous like Modest Mouse or Built to Spill. They weren’t disaffected. Or twee. They weren’t Punk. And though somebody online called them “Emo,” they sounded absolutely nothing like The Promise Ring or Texas is the Reason. It was just spare guitar, bass and a small drum kit. The songs had so much space in them, like Bedhead and Karate, who were tagged “Slowcore.” But whereas with those bands, I had to sit patiently for the sound, with Pedro, I had to sit patiently for the feelings. True to its title, the “Whole” EP is about fracture and repair. It seemed that Humanity was at the root of the former and Jesus, the latter. Objectively, I knew that this was “Christian Music.” But I did not care. The melodies were so elemental as to sound like something beyond Folk. They sounded hymnal. But that singer. Where did that voice come from? Where did those feelings come from? His voice felt like corduroy and flannel. It was all chest—straight from the heart.

Throughout the next year, I set a course to find out. I returned to the Tooth & Nail Records website. I read some online reviews from Christian Rock devotees. I bought albums from bands with names like Joe Christmas, Sal Paradise, Starflyer 59 and Roadside Monument. For the better part of 1997 and 1998, these decidedly Indie, semi-Emo, Christian bands were all I wanted to hear. I didn’t come for the scriptures, I came for the sincerity. Apparently, I needed something to temper the years of the Blues Explosion and the Beastie Boys and this burgeoning scene out of the Pacific Northwest was my tonic.

In the early winter of 1997, I cashed in my meager bonus from work to fly to Portland for the North by Northwest (NXNW) music festival to see Pedro the Lion. They played an all ages venue where I stood, speechless, alongside a dozen or so fans and thirty less curious barflies. But there they were. They were real. Three pieces. David Bazan was the lead singer—that voice. He sang and played with his eyes closed. And he sounded exactly like he did on that record -- warm and sweet, but possibly broken. He had the beginning of a beard and the ending of a hairline. He was only twenty-one but he had the eyes of a seventy year old. He had the look of a manchild, like he could either be a lumberjack or a little league pitcher. Or both. I was too nervous to go up and talk to him after the set. But I remember that show very clearly to this day.

I returned to New York and my job at a record label unsure whether I should report back to my colleagues about this hidden gem or to just keep the secret to myself. It seemed, at the time, that nobody outside of Christian music circles had heard of Pedro the Lion. And they seemed almost too earnest to invite into the Industry (with a capital “I”). So, I just played their EP on my headphones, waiting for a proper full length to arrive, checking the internet for news and using my SoundScan login to see if anyone was actually buying their record. A seven inch soon followed and then came reports of an album, entitled “It’s Hard to Find a Friend.” That title—the vulnerability—sounded unbearable. There was no way this band could play in New York City. The Strokes and Yeah Yeah Yeahs and LCD were still a couple of years away, but the Lower East Side was the land of CBGBs, Mercury Lounge and disaffected pretense. I knew it well because I wanted it. But I also wanted Pedro the Lion—just not in my backyard.

In the fall of 1998 as part of the CMJ festival, as if on a mission, David Bazan and his band came for us heathens. I marked the date and cleared my calendar. I was ecstatic, but also told no one about the show. It didn’t matter. People found out. As I made my way up the stairs to the Threadwaxing Space -- an experimental art gallery that very occasionally hosted concerts—I began to feel a crowd. Just a year ago, in Portland, 175 miles from their home, Pedro the Lion could not fill a small, all ages venue. One year later, they had a couple hundred curious hipsters and assorted believers from across the river filling a Soho art gallery. It made zero sense to me. But, at the same time, it was wonderful.

That night Pedro shared the stage with David Bazan’s high school buddy, Damien Jurado. Jurado was cut from a similar cloth as his friend —big boned, gorgeous voice, songs that were kind of writerly and kind of painterly. But, most importantly, completely heartfelt. I don’t remember hearing a peep from the crowd that night. I do remember my eyes welling and my throat closing more than once and that, when I looked around to see if anyone noticed, that there were other people in the room fully bawling.

I could never have predicted what happened over the next few years. Pedro the Lion won over Indie America. Obviously, I was not surprised that they would have hometown success or that they could find audiences in smaller cities, where churches doubled as all ages venues. Those listeners flocked rather quickly. But David Bazan’s band went to Chicago, the land of June of 44 and Touch and Go Records and Math Rock, and they won over the Windy City. Then they headed South to Dallas and Austin and Denton and College Station, and, in the land of Bedhead and American Analog Set, they fit in quite nicely. Next, they filled the Cat’s Cradle, in Merge Record’s hometown, and the 930 Club, on Dischord Record’s home turf. Finally, they made their way back through the Northeast, where churches were more quaint than vital, and they filled the Knitting Factory, in TriBeCa, and The Middle East, in Boston. Each year, however, the band returned like conquering evangelicals to Grayslake, Illinois for the Cornerstone Festival, where they performed for thousands of young Christians.

Fans of Indie Pop adored “It’s Hard to Find a Friend,” from 1998, and “The Only Reason I Feel Secure,” from 1999. For one brief moment, it seemed that everything was lining up for David Bazan’s band. A whole bunch of us—not quite kids and not fully adults—set aside our religious beliefs to sincerely listen to a band sing about godfulness and its antonym. I checked SoundScan reports -- Pedro the Lion were selling thousands of records. Eventually tens of thousands. During a time when Spoon could not sell half that amount and before Modest Mouse and Death Cab crossed over, Pedro the Lion was on the verge of something that was on the verge of something even bigger.

In 1999, and before many people cared, Pitchfork adored the band. A year later, however, the midwest tastemakers felt much differently. In a review that seemed ungenerous even by 2000 Pitchfork standards, and which is curiously not on the website anymore, “Winners Never Quit” was lambasted as dull and overly serious. While the first suggestion is untrue, there was certainly a case to be made for the latter. With his band’s success, Bazan also had to confront an ever growing crisis of faith. And with each record, the questions got heavier: Do his fans need to believe the way he believes? Can you be loved by the faithful and the godless? Is the life of a musician amenable to Christianity? Can you be a good husband if you are married to the road? Can you be a good father? Can you make a living as an Indie Rock semi-star? Is it bad to want more money? Is it bad if I make more money than my bandmates? And then, most troubling of all: what the fuck is happening with Christianity?

Pedro the Lion just could not find their way to the other side of those questions—but they got especially hung up on that last one. Bazan questioned and questioned and wrote and sang and toured and then questioned some more. His songs began to suggest an anxiety of faith and a cynicism about some of the faithful. He appeared unable to reconcile his original charter for Pedro the Lion with his new perspective. And, to make matters much simpler and much worse, he began drinking heavily. In a Washington Post article from 2004, it was revealed that Bazan carried a two gallon jug of watered down vodka with him to the very dry, very Christian, Cornerstone Festival. Though the signs were all flashing, right there in his music, the vodka “no no” landed the singer at the crossroads.

The path Bazan chose was likely the harder one. He broke up Pedro the Lion in 2006, dried himself out, and elected to return to music, as a solo artist, playing tiny, living room shows to anyone who wanted him, all over America. For almost a decade, during formative years for his children and difficult years for any family, he made a living by driving around in his car, alone, singing for intentionally small crows, one hundred and fifty nights a year. It was a living. In the high days of file sharing and before streaming music services, it was probably a steady and clever way to make money. But, at least based on Brandon Vedder’s excellent documentary, “Strange Negotiations,” it was lonely as hell. It was years seeing his kids grow up over FaceTime. It was nights in cheap hotels or on the couches of kind strangers. It was months on the highway, watching mile markers pass glacially as his middle-aged hour glass sucked grains of sand down at twice the rate of his minivan. In almost every way, it appeared gutting.

In almost every way—but not every way. During those years, alone on the road, Bazan could not stop searching. And, in his search, he found others who were also searching. Every night, at every show, and every day, in every interview and podcast, he was asked about his relationship with god. And his feelings about Christianity, in general, and Evangelicals, in particular. In between songs, in people’s living rooms, more often than not, he’d be fielding questions from Believers, who had their own questions, and from lapsed Evangelicals and Christians-turned-atheists and all of their friends. Each night, after hours sinking into the front seat of his car and choking up to text messages from home, Bazan stood up, sang his songs, and answered those questions with a truth and vulnerability that is hard to fathom. He would play those songs, slower than Rock or Folk music but faster than hymns, and would sit with the spaces in between. And to take in those questions—some of the accusing and others quite desperate—and to share what it had been like to break up with his best friend, who also happened to be Jesus Christ, and to write about it and sing about it every night, knowing that it might be ruining his career and his marriage. That was fucking brave. I love Brene Brown and her acolytes. But I can say that I’ve never seen a person so awe inspiringly vulnerable as David Bazan in “Strange Negotiations.” While his former “family” was making their deal with Donald Trump, Bazan was going house to house, playing concerts and fielding questions about his journey from the Pentecostal Church to a living room of strangers.

All of that searching eventually led Bazan back home. First, to his family, whom he desperately missed. Then, back to Pedro the Lion, the moniker he’d hung up but which had accrued value during its hiatus. And finally, ultimately, to Phoenix, Arizona, the place where he was born and where his earliest memories of god and family come from. By 2015, when he was dining at gas stations and hocking merch from the trunk of his car, it appeared that Bazan’s road to nowhere might be endless and godless. Just two years later, however, he’d found revelation. He missed his family. He missed having a band. He missed Pedro the Lion. He needed all of those things. But he also needed to make as much (or more money) than he did as a minivan troubadour. In retrospect, of course, it was all so obvious. The answers were right there, logical to the point being existential.

And so, in 2017, David Bazan resurrected Pedro the Lion—first for a few shows, and then for the longer haul. A year later, he announced that would be releasing an album about Phoenix, Arizona, where he spent his earliest years growing and believing. He was forty something—balder, thicker in the middle and sadder around his eyes. But he still wrote songs like fables and he still sang like a lumberjack slash little leaguer in corduroy and flannel. Since 2000, he’d hopped from legendary Emo label, Jade Tree, to Indie stalwart, Barsuk Records, and then back near Emo’s roots on Polyvinyl Records. He’d traveled every corner of America having the hardest conversations imaginable, and he was, finally, ready to go home, again.

“Phoenix” was released in January of 2019, fifteen years after the last Pedro the Lion record and while more than half of America was wondering if Evangelical Christianity had lost its way, or been kidnapped, or something worse. There was, of course, a degree of nostalgia surrounding the early “comeback” shows. But, beneath that, there was an ever deeper sense of appreciation for Bazan’s journey. His religious faith had been broken along the way, but his hope had not.

The distance between the world Pedro the Lion left in 2006 and the one they returned to was staggering. Musically, the seeds that Bazan had planted could be heard blossoming in Sufjan and Fleet Foxes and, to a certain extent, The Shins and Death Cab. That gap spans all of Obama’s presidency, the rise of Trump, the brazen ascent of white nationalism and its uncanny proximity to evangelical Christianity. 2019 was the pre-pandemic world of echo chambers and clickbait and Instagram and algorithms. Ideologies were fixed and nobody wanted to listen to anybody else. It was probably a terrible moment to release an obsessively personal album about revisiting and reclaiming your own childhood. On the surface, and especially if you did not know the miles that Bazan had traveled, there was something highly solipsistic about the whole affair. But, on the other hand, Bazan had actually traveled all those miles. And they led him back to Phoenix. So, whatever the musical climate or political climate, this was really the only album Pedro the Lion could have made upon their return.

As a concept, “Phoenix” reads sprawling and ambitious. As an actual song cycle, it is much more modest. The songs range from down the middle, 90s Indie Rock, to moodier, math-ier contemplations to fleeting sketches. Bazan has always been writerly in his craft, but there are moments on “Phoenix” when his literary skills sound like captions to snapshots or notes to self. This is no indictment—the album would lose some of its vulnerability if every idea was varnished with guitar hooks and succinct choruses. Travelogs can read like notebooks and memories can read like random asides. In that way, Pedro the Lion’s comeback album is as much a notebook of memories as it is a baker's dozen songs.

“Phoenix” opens with the sound of ambient crackle and a moody church organ. While the short instrumental portends a dreamy vibe, it’s not a particularly happy one. After sixty seconds, the opener falls in on itself, suggesting that the memories to follow will be either fractured or dark, or both. While there is, of course, some truth to the foreshadowing, the next two tracks are among the most cogent and spirited on the album. “Yellow Bike” has a ringing hook, and a pace that’s steadier than most Indie Rock but slower than most Emo. It’s 1981 and Bazan is getting his delicious first tastes of freedom, peddling away from home. But, as he recalls it, that independence was accompanied by a certain amount of loneliness -- he was riding solo, into the sunset. Immediately, he draws a connection—real or imagined—to his later self, driving alone along America’s highways to his next gig. On one level, he is unencumbered. On many more levels, he is alone.

The guitar remains forward and dialed up for “Clean Up,” a tight, little rocker that draws the line from cleaning up your bedroom to confronting the piles of mess in your adult life. There’s something parabolic about many Pedro the Lion songs. This one may be even simpler—more childlike in its metaphors—than the band’s biblical allusions. It’s not especially clever on its face, but it effectively conjures the feeling of a grown man in conversation with his much younger self. And vice versa. And, as Bazan has done countless times over his career, there are unexpected moments where he pushes his heavy pipes up a register, reaching for something higher. And, as always, he finds it. In his forties, Bazan’s voice is more barrel-chested. But he still has all of the range and an added sense of depth and vulnerability. There’s really no one else I can think of who sings like he does.

Most of “Phoenix” arrives in figurative sketches. The songs are either short and bittersweet or slightly longer but less conventional in structure. “Model Homes” and “Black Canyon” share a meandering, math-ier pacing. But they also manage to find their way through the stories and back to the idea. The former is about humility and shame and wanting more and then the shame of wanting more. It clearly evokes the modest lives of a Christian family, growing up in the Southwest in the days between Carter and Reagan. The latter is a much darker, more dissonant story about a suicide, an eighteen wheeler and how trauma stories cannot stay buried. These middling, slow, slower, less slow numbers are not terribly far from Slint or Bedhead, except their paired with the honesty of a child’s memories.

Bazan is more successful on “My Quietest Friend,” wherein he hammers down on the guitar, drums and—most of all—himself for turning his back on his titular friend in favor of his rowdier buddies many years earlier. It’s a poignant memory, but a relatable one for anyone who’s ever leaned away from loners, wallflowers and introverts and towards youthful peer pressure. It’s obviously too little too late, but I suspect that is the entire point of the song. On the other hand, Bazan genuinely, and desperately, hopes that he is not too late to help the city that inspired his album. On “My Phoenix,” he considers the place he’s returned to, no longer young and innocent. His Phoenix—or at least a big part of it—is waving red and white flags. It’s rooting for closed borders. It’s a hotbed of conspiracies and misinformation. There’s nothing innocent about his hometown in 2019. And yet, he’s praying that it will rise again. It’s not a Christian prayer, but it’s full of faith, nonetheless. On an album that could have also been a scrapbook, it’s not the most obviously personal song. After all, it’s about a city, not a child. But it is also about innocence lost and found. And here Bazan delivers his more soaring, emo-ish vocals. If you were not around for the full Pedro journey, this track, in particular, and the album, in general, could feel cloying and self-obsessed. It is certainly both of those things. But, more so, it is courageous and true. The thing that always struck me about Pedro the Lion was not that David Bazan knew things that other signers did not, but rather that he felt things more deeply.

“Phoenix” is a beautiful album—a lyrical album. But it does not give me the chills the way the “Whole” or “The Only Reason I Feel Secure” EPs did way back when. Many years after identifying as an unlikely believer, and then as a lapsed fan, however, I am so grateful for the band’s return. In my mind, David Bazan will always be connected with his friend, Damien Jurado, who has enjoyed a more staid, linear career. To me, Jurado seems like a genuine troubadour -- he follows the muse and the road. Bazan seems, almost tragically, like a searcher—he questions every idea and every fork in the road, wondering what he might find and where he might get lost. In middle age, Jurado shed his baby fat and the deep lines in his smile offset any torture in his voice. It appears that he’s come out the other side mostly intact. Bazan, on the other hand, can look and sound broken. But the bravery of his journey -- house by house, believer by believer, atheist by atheist—is nothing short of astounding.

In 1998, I choked back tears in Soho when Pedro the Lion performed “Almost There,” for fear that I’d be outed by the surrounding artist types and college radio DJs. Two decades later, as I watched footage of Bazan performing in living rooms across America, I remembered that feeling. I saw the effect he had on listeners. The effect of a man who was holding the truth and doubt together, at the same time. And how heavy that weight must feel, miles from home. Away from your partner. Away from your kids. Away from where you came from and how you were taught to be. Knowing that every minute you are living you are also dying. It sounds like a fable. Or a fever dream. It’s all kind of eviscerating, and I’m not entirely sure why. I suspect it’s somehow related to that dream I keep having about trespassing in my own childhood home. The one I’ll never reckon with. The one that’s just too much. I’ll never look at it squarely. I’m certain of it. But David Bazan did.