Bob Horner “Mr. Ho Mah”

In childhood, we have far fetched dreams about what we might do when we grow up. These fantasies often have a wonderfully naive careerism about them—“when I grow up I want to be a professional athlete or a famous actor or an astronaut”—but rarely are they rooted in reality. At some point one of our parent’s friends might semi-seriously inquire about our future plans, and we might even have a cute answer. But rarely is it deeply considered. It’s almost never based on our aptitudes or any market realities. It’s all just make believe. Which is why, as we grow up and leave home, these reveries get replaced with anxieties. The playful imagination of what we might do for work is quickly subsumed by the dread of what we can do or what we must do. That trading of dreams for reality—a right of passage in life for young adults—is rarely thrilling. It’s sometimes depressing. And occasionally traumatic.

Eventually, if we survive our angst and make it through the crucible, we end up with something resembling a career. If we’re lucky, we find some version of success and make enough money to buy the things that we need—and maybe a few that we don’t need, but really want. Eventually, we’ll have something to lose. We’ll become circumspect. We’ll have long since stopped thinking about what we might become and instead, we’ll start to wonder what we might have been. Or we might become consumed with retrospection and ask ourselves, “what was I born to do?” We’ll look at our friends’ profiles on social media and consider the other roads not taken. We’ll listen to The Talking Heads “Once in a Lifetime” with discomforting relatability. By then, we will have been doing something professionally for decades. We’ll be pretty good at it. It’s what we needed to do. But we'll have absolutely no idea what we really wanted to do. Or what we could have done. Or what we should have done.

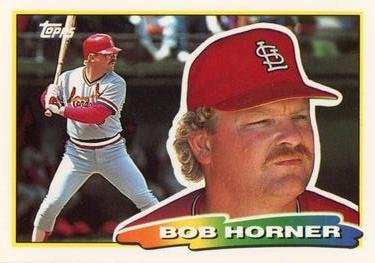

James Robert Horner, known professionally as “Bob,” never had any of this angst. He was born to use his hands and arms to strike objects with tremendous force. I suppose he could have been a great boxer, though that profession risks great injury. If he’d been born abroad, maybe he’d have become the most decorated cricket player of his generation. He was (and probably still is) a gifted golfer. He could have been the MVP of a building demolition company. Those were all possibilities. But when you’re built like Bob Horner was built and born in Kansas in the late 1950s, there’s really only one job for you—playing baseball in the Major Leagues. Even when he came up as a rookie in the 70s, Horner looked physically different from every other major league hitter—blonder, bigger in the chest and forearms but more compact everywhere else. Forty years later, his baseball cards appear almost comical. Fair mullet, crusty mustache, huge chest, noticeable gut and ankles that seem too small to carry his weight. By the mid-80s, Horner resembled the love child of Babe Ruth and Kenny Powers. It was unthinkable that he would do anything else with his life other than hit home runs and make terrible hair decisions.

Bob Horner was a slugger from the get go. After his family left Kansas for Arizona, he was regarded as one of the country’s elite baseball recruits. He stayed near home and attended Arizona State, where he obliterated home run records and led the team to a College World Series championship. In 1978, he was drafted with the first overall pick by The Atlanta Braves, who were owned and functionally managed by media mogul, Ted Turner. That same year, without ever playing a single game in the Minors, Horner made his Major League debut. Less than one hundred men have ever made the jump from college straight to The Big Show. In roughly half a season, and during an era of statistically depressed hitting, he hit twenty three home runs, slugged over .500 and won Rookie of the Year honors. By any standard, he was a power hitting savant. Early news articles obsessed over the brute strength and radical efficiency of his swing. How natural it looked. How he was a “guess hitter” rather than a “thinking hitter.” How he crowded the plate and dared pitchers to throw inside. How he rarely walked or struck out. How all he did was hit balls hard, frequently pulling them over the left field fence. Horner was flaxen and from the Heartland, but didn’t look like Robert Redford. He wasn’t The Natural—but he sure as hell was “a natural.”

There’s a long history in baseball of young phenoms taking the game by storm. Some of them flame out fast, like Mark “The Bird” Fydrich. Many others, like David Clyde or Billy Beane, never even shine at all. Of the players drafted first overall, a surprising number have gone on to have very good careers. But Horner was not legendary like Ken Griffey Jr. or Chipper Jones. He also wasn’t a great, self-sabotaging talent like Josh Hamilton or Darryl Strawberry. He only played in the Majors for a decade, so it would be unfair to liken him to venerable journeymen who were also top picks, like B.J. Surhoff or Jeff Burroughs. Baseball Reference compares him to Al Rosen, which may be statistically accurate, but obscures the fact that Rosen’s prime started later and ended much sooner on account of World War II. Bob Horner was always his own thing—an objectively great power hitter whose career was threatened by a team owner, overshadowed by a more telegenic teammate and ultimately curtailed on account of injury and self care. He played ten seasons in the Majors and one unforgettable season in Japan. And he was exceptional for all but one of those years. He was exactly fifty percent a Hall of Famer. But he was probably two hundred percent slugger.

In 1979, one year after winning Rookie of the Year honors, Horner found a season-long groove. He hit over .300 and slugged over .550. He placed just twenty-eighth in the MVP balloting, but, based on his performance at the plate, was probably the fifth or sixth best hitter in the National League. Unfortunately, his team, The Atlanta Braves, were awful and they were run by a great businessman who was an incompetent manager. The next season, when the team started out with just one win against nine losses, Ted Turner did the unthinkable—he optioned Bob Horner down to The Minors. Horner had started the season slowly, but there was genuinely no precedent for an owner demoting the second best player on his team just two weeks into the season. In an appropriately forceful response, Horner refused to report to AAA. He simply said “no,” stayed at home, and waited out ownership. Three weeks later, Turner relented and Horner returned to the team, vengefully mashing home runs for the rest of the season.

The winter before his minor league standoff with Turner, Horner’s agent Bucky Woy, had won a grudging contract negotiation against Braves GM, Bill Lucas. Shortly after, Lucas died of a brain hemorrhage and cardiac arrest. Turner immediately and very publicly blamed Woy, and implicitly Horner, for Lucas’ death. Known as much for his pettiness as his success and good looks, the Braves’ owner never let it go. Even after he beat Woy’s (possibly justified) libel case in court in 1983, he took every opportunity to punish the quiet, husky slugger at the center of the drama. Horner never bit. He’d answer questions from reporters honestly. But he never belabored the issue. He seemed unwilling or unable to fathom the theater of it all. He just wanted to hit home runs.

Between 1980 and 1986, whenever Bob Horner was on the field, he was among the best power hitters in the game. He didn’t carry a gaudy average and he didn’t get on base like today’s players, who’ve harnessed the wisdom advanced analytics. But he almost always hit the ball hard or far or both. Unfortunately, he had several strikes against him. First, there was the rancor of his team’s owner. Second, there was the club’s performance. In spite of a wealth of offensive talent, The Braves were only briefly above average during his tenure. And third., there was the third base of it all. Horner was an obvious defensive liability. In comparison to the great third basemen of his day—Mike Schmidt and George Brett—he simply never compared. And yet, his most obvious competition was back home in Atlanta. Every year that he was a Brave, he played alongside Dale Murphy, who was just slightly better at everything. Murphy hit for more power, drove in more runs, stole more bases and made fewer errors. And, to boot, he was taller, leaner, more telegenic and Christian.

By the end of 1986, it was clear—Bob Horner was exactly who he was. He was not going to get much better or stronger or faster. He would never be Dale Murphy or Mike Schmidt or George Brett. His hair would grow longer in the back though less so up top. He was good for twenty-five to thirty home runs when he avoided injury. And he eventually moved away from third base, out of harm's way, and over to first. He was consistently well above average and occasionally even better. In his final season as a Brave, on July 6, 1986, he became just the eleventh player in baseball history to hit four home runs in a single game. Appropriately, The Braves still lost the game.

At the end of that season, Major League owners colluded, refusing to sign any free agents and effectively depressing player salaries. Horner, coming off a pair of mostly healthy, mostly productive seasons, was a victim of the crime. Rather than remain on a losing team near the disdain of his owner, however, he did something completely unexpected: he signed a million dollar contract with the Yakult Swallows in Japan. Unwanted in Atlanta and undervalued in The Majors, Horner, still only twenty eight years old, became “Mr. Ho Mah” in Tokyo.

He was an immediate sensation, starting off the 1987 season seven for eleven, with six home runs in only four games. His unsustainable pace, however, leveled off once pitchers refused to throw him strikes or fastballs. Never fond of taking a walk, Horner grew frustrated and isolated on the other side of the world. In roughly three quarters of a season, he still hit .327 with thirty one home runs, and was indisputably one of the very best hitters in the league. But he bristled at the idea that pitchers were avoiding him. He considered it cowardly and not in the spirit of the game that he grew up playing. So, by the time the season ended, and in spite of a very lucrative contract offer, Horner wanted to get back home. He appreciated the opportunity. He learned a lot. He’d traveled the world in pursuit of his genetic need to hit home runs. But, he was done with the experiment. On his way out, his terse, but sincere, recounting of his time in the JPCL infuriated local fans. He was cast as impolite and as a sore loser. But Horner didn’t mind. He thanked his teammates and coaches, packed up and headed home, hoping to find a team that needed an increasingly injured and overweight, natural born slugger.

Although the offers were not plentiful or generous, Horner ended up joining the Cardinals. Against the wishes of manager Whitey Herzog, Horner was signed to replace first baseman Jack Clark. Clark had just completed a career year, leading the league in multiple categories and finishing third in the MVP race, only to then sign a lucrative deal with The Yankees. Cardinals fans decided to view Horner, who was still only thirty years old at the time, as a glass half full. No matter the context and no matter his physical limitations, all they’d ever known about Bob Horner was that he hit home runs.

Before the season started, hopes were medium high. There were mentions of his bum shoulders and his awkward eyeglasses and his increased girth. But that did not fully dampen enthusiasm. What eventually did ruin the honeymoon, however, was his sudden, and prolonged, lack of power. Many blamed it on injuries that would require season-ending surgery. Whitey Herzog claimed that he’d predicted the struggles, pointing out that Horner’s power in Atlanta was almost exclusively to a short fence in left center field. At Busch Stadium in St. Louis, that area was punishingly out of reach. Both diagnoses were probably accurate. And, also, Horner was probably tired and a little out of shape. The root cause may be irrelevant. What mattered is that, after sixty games, Bob Horner was done. He’d hit two home runs in April. One in May. And then, on June 18th, he went one for one, with a double and an RBI as a pinch hitter. He never played professional baseball again.

In 1990, after a year plus of rehab, Horner half-heartedly accepted an invite to Orioles spring training. But he politely walked away before it became anything at all. He knew he was finished. Since he was a child, all he could ever do was hit home runs. But, at thirty two, he couldn’t do that any more. He retired with an oWAR of 28.2. Had he stayed healthy for another decade, his career numbers would have resembled Harold Baines or Jim Rice, both of whom are (controversial) Hall of Famers. But that’s not the hand Horner was dealt. He was the rare instance of a phenom who almost, if briefly, lived up to his potential, but could not exceed it or sustain it. He was never the best. But he was also never a tragedy. There’s no “what if” to his story.

Some players the caliber of Bob Horner have complicated second halves as Minor League coaches or Major League hitting instructors or suburban car dealership owners. This was especially true in the last millennium, when retired players still needed to make a living after their playing days. Most of these men were wholly unqualified for any jobs outside of baseball. As children, they’d never wondered what else they might do when they grew up. They were elite athletes. Their dreams were defined by a biological imperative to succeed athletically. Nobody suggested they become doctors or lawyers or general managers. As almost middle aged adults, however, they were confronted with the roads not taken. Should they hang around baseball or should they invest in their buddy’s nightclub or should they try that thing that they wish they’d considered twenty years earlier? Bob Horner seemed disinterested in that sort of introspection. When he retired, he really retired. He coached his son's Little League teams. He played golf. He traveled with his wife. Occasionally, he’d show up at old-timers celebrations where Braves’ fans remembered him fondly. Baseball card collectors obsessed over his mullet and his physique. But Horner genuinely seemed to have zero regrets. He did what he was born to do. He did it at the highest level. And when he couldn’t do that any more, there were really no questions. I mean, what else would he do?