Dwight Evans “The Unfathomable Dewey”

When folks talk about the 1975 Red Sox, they frequently talk about Lynn and Rice, and more frequently talk about Carlton Fisk and “Game Six.” But what almost nobody mentions is that Dwight Evans, their great glove/some bat right fielder, notched 5.1 WAR that year. By comparison, Jim Rice had 3.0 and Pudge Fisk had 3.2. On a pennant winning club that included Yaz, Lynn, Rice, Pudge, El Tiante and Spaceman, and who nearly bested The Big Red Machine, Dewey was the other young kid. Which is kind of the story of Dewey’s career—always a groomsman but never the groom, except for those eight seasons when he was actually the best man or those four when he was actually the groom.

Jeff Kent “The Enemy of Your Enemy”

In the winter of 1996, having already been traded twice in his young career, Jeff Kent was traded again—this time to The San Francisco Giants, where he both blossomed and soured. Alongside the Barry Bonds—the slugging, running, intentionally walking, video game centerpiece of the club—Kent helped lead the team to six straight winning seasons. Moreover, while in The Bay, Kent averaged thirty home runs with a hundred RBIs and a .300 average year in and out. And yet, to this day, Jeff Kent is perhaps less remembered for his offensive prowess than as Barry Bonds’ most offensive antagonist.

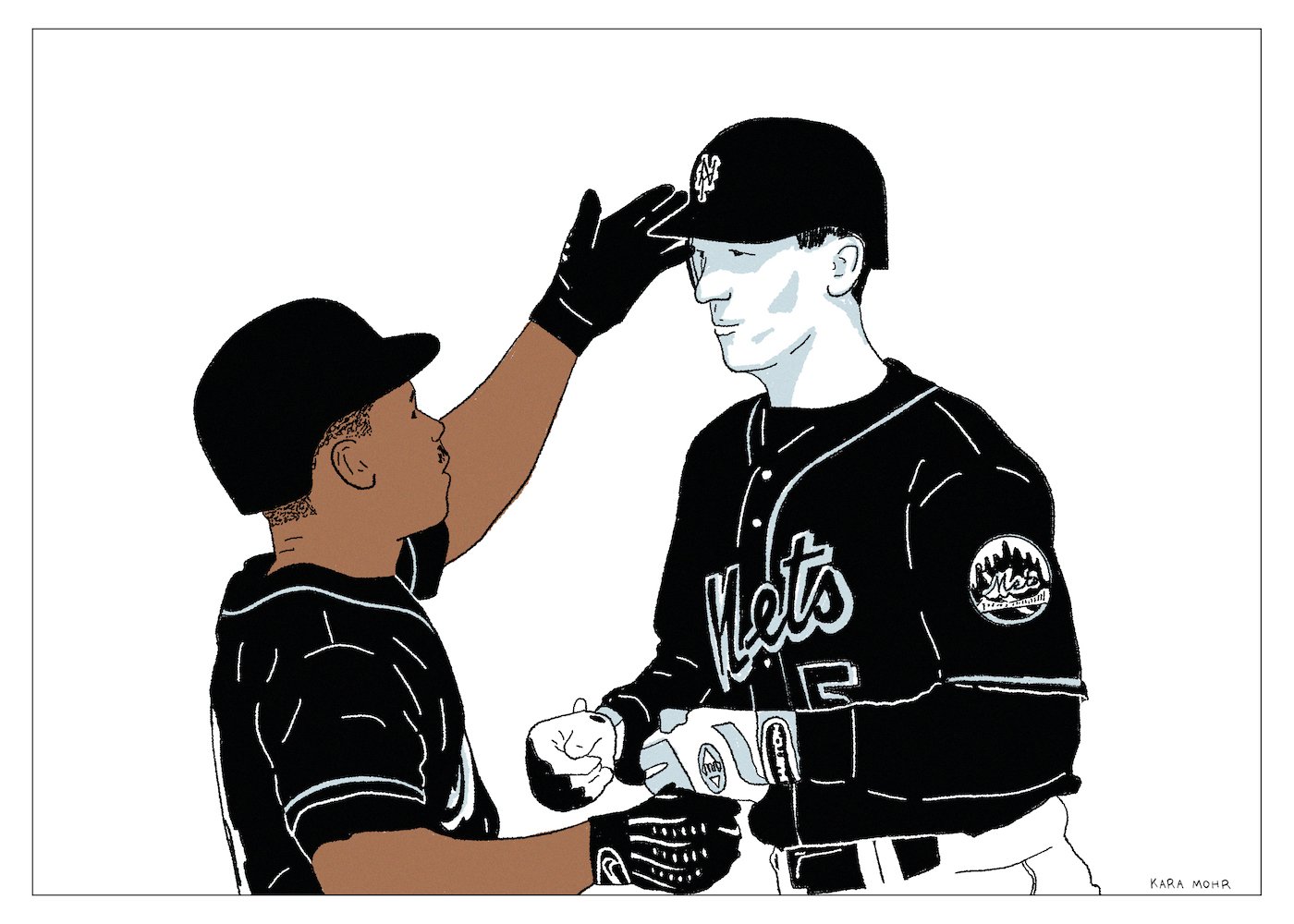

John Olerud “Un-unforgettable”

There are several permutations of the “Rickey and Oly” story, including hysterically far flung versions wherein the latter is basically Jesus. But, regardless of the version, the fundamental premise remains consistent. And as short stories go, this one is a formal marvel. It’s got a great setup and an even better kicker. It’s succinct and hysterically funny. It confirms our assumptions that Rickey Henderson was both extremely perceptive and completely oblivious — that he was operating on a different plane and dimension from “normal” stars. But moreover, it acknowledged the thing that every baseball fan knew to be true but which none would say out loud: that John Olerud is un-unforgettable.

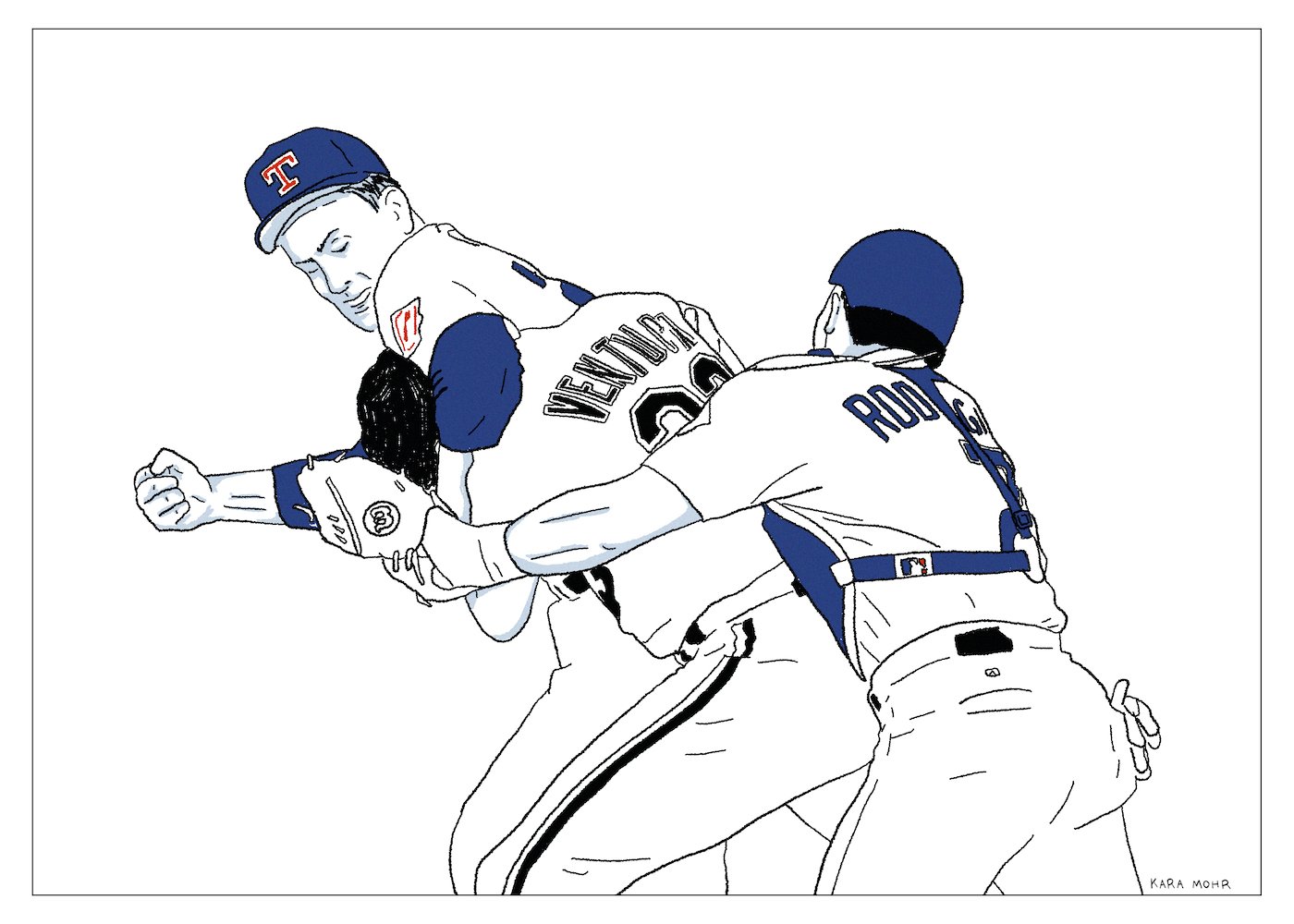

Robin Ventura “The Misremembrance”

His “grand slam single” during the 2000 NLCS would have been the most memorable event from almost any other player’s career. So would have the two grand slam game or the two grand slam double header. So would all those gold gloves. And that’s not to mention anything of the fifty-eight game collegiate hitting streak. Any one of those feats would have been a career hallmark for most ballplayers. But not so in the case of Robin Ventura who, on August 4, 1993, dared to charge the mound inhabited by one Nolan Ryan.

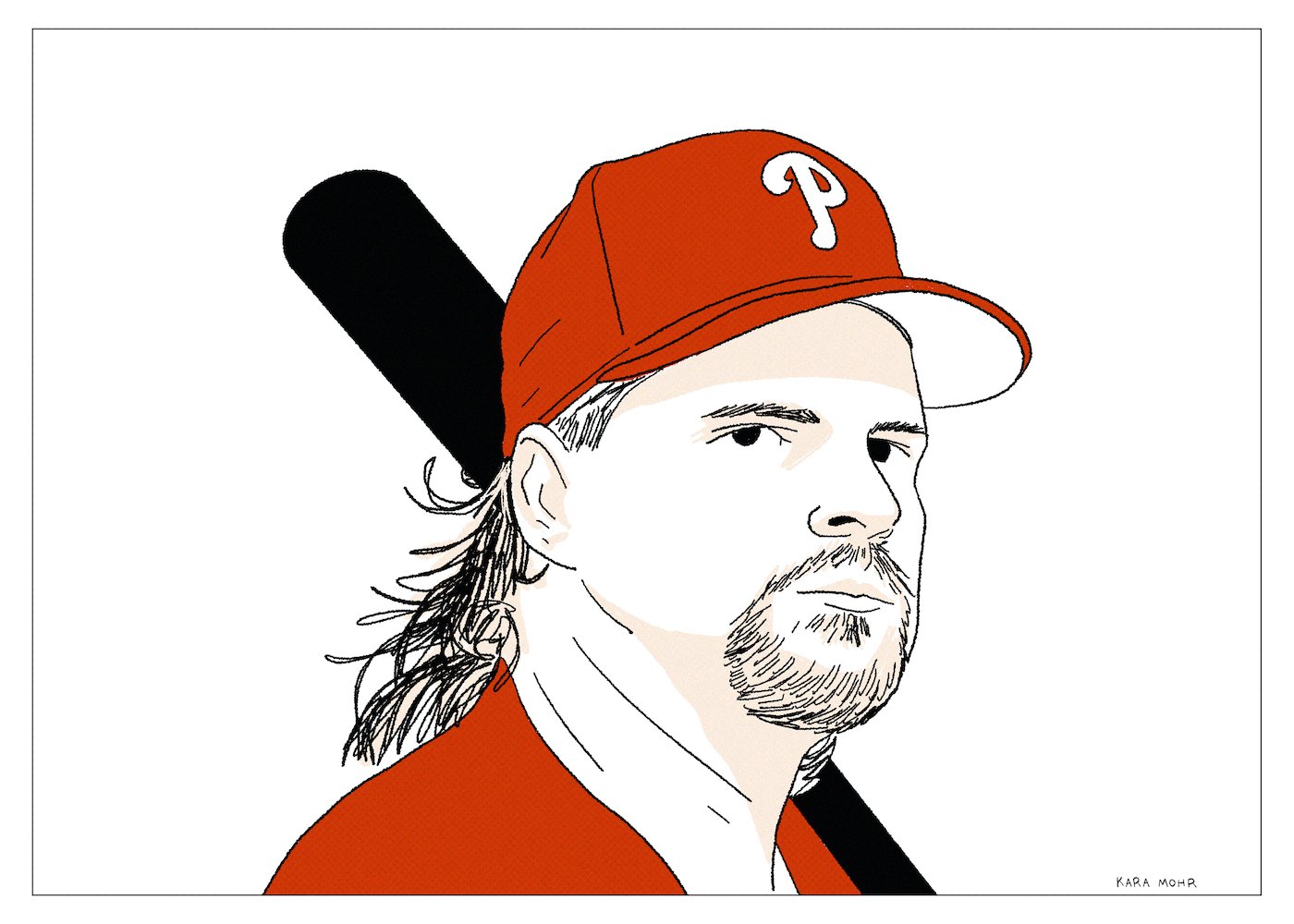

John Kruk “The Mullet Gives You Permission”

In 1972, President Richard Nixon made a diplomatic visit to mainland China where he finally, formally recognized the Communist government. Conventional wisdom suggested that only Richard Nixon, with his unimpeachable anti-communist bona fides, could have made such a conciliatory move. In the case of Nixon and China, for the truth to be heard, a very specific messenger was required. Twenty one years later, baseball got its Nixon and China moment when John Kruk faced Randy Johnson in the third-inning of the 1993 All-Star Game. During that legendary, if swift, at bat, Kruk revealed a truth that had been suppressed for years and which he alone could effectively convey: baseball is terrifying.

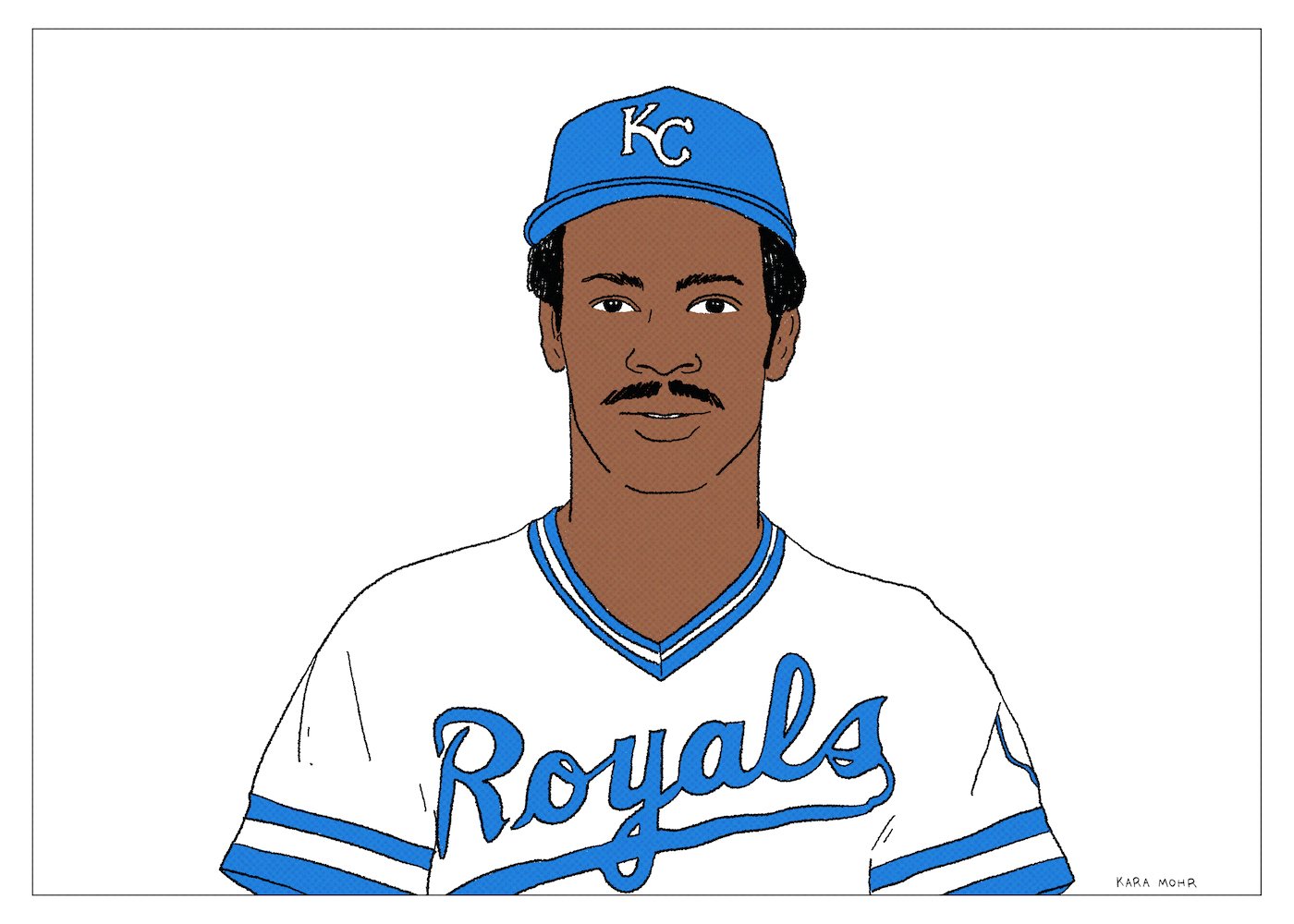

Willie Wilson “Speed Kills”

It is a cliche to suggest that, in life, your greatest blessing becomes your curse — that your feature becomes your bug. But in the case of Willie Wilson that seems especially true. So gifted, so fast and so strong, Willie could have been an All Star in most any sport. But the sport he chose was the one which least suited his particular genius. There’s a certain tragedy in knowing that you can surely do things that no one else in the game can do, but at the same time knowing that those things only matter so much in your chosen game.

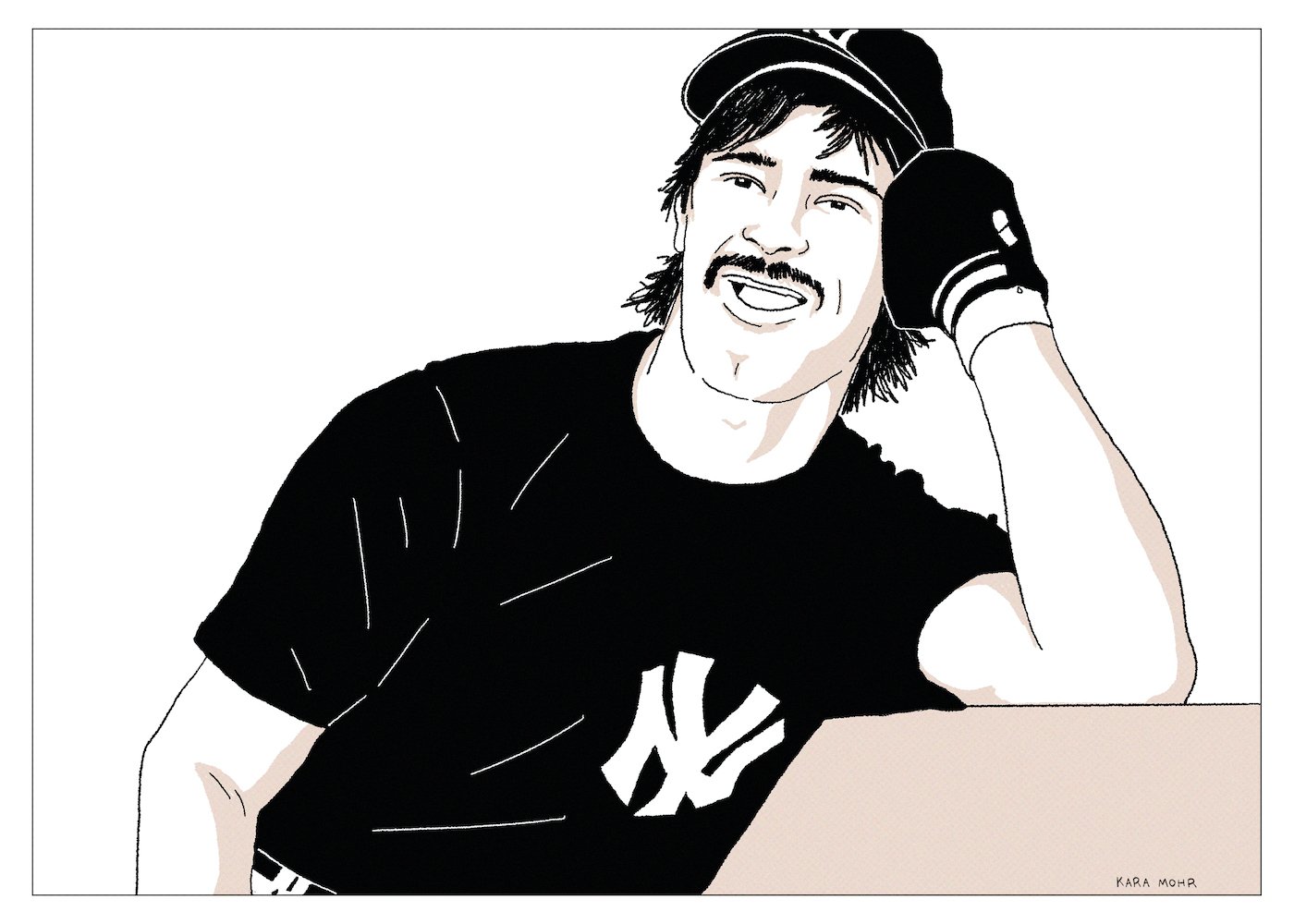

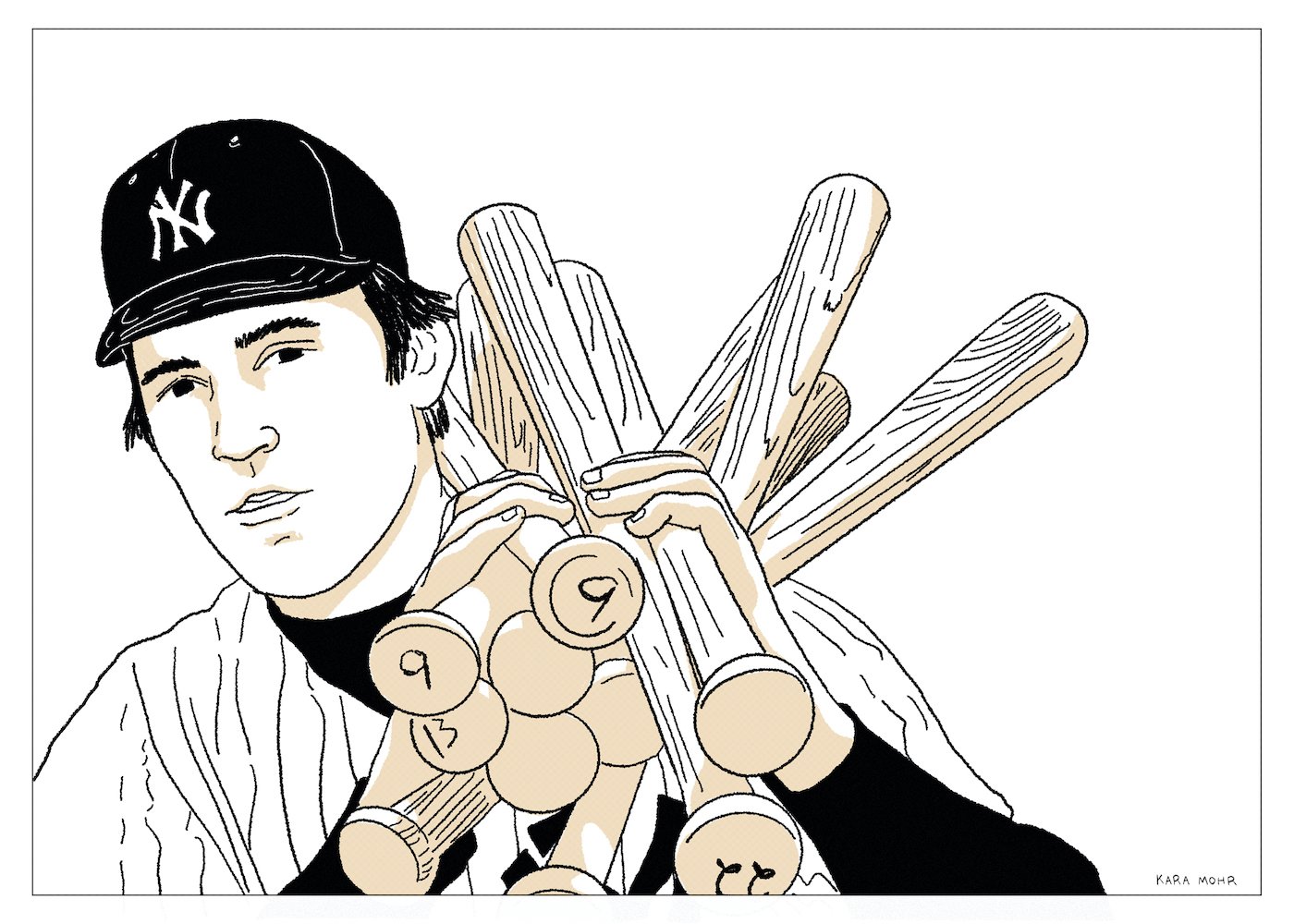

Don Mattingly “The American Dream”

By the time Don Mattingly became the Yankees’ captain in 1991, the franchise had already won twenty-two World Series championships. They’d not won one, though, during Mattingly’s career. In fact, they’d not even been to the Fall Classic. But during his final season in 1995 — a season in which he limped his way to seven home runs and 49 RBIs — the Bronx Bombers finally made it to the playoffs. According to the story of The American Dream, Donnie Baseball’s work ethic should have been validated by a championship ring before he was put out to pasture. And, true to form, he tried. The badly hobbled Mattingly — as one last testament to the power of will and determination — hit .417 for the series with six RBIs and a magical go-ahead home run in Game Two. But, in the end, the Yankees lost, Mattingly retired and returned to his horse farm in Evansville. The next year, without Mattingly, the Yankees would win the World Series. And then again three more times in the next four years.

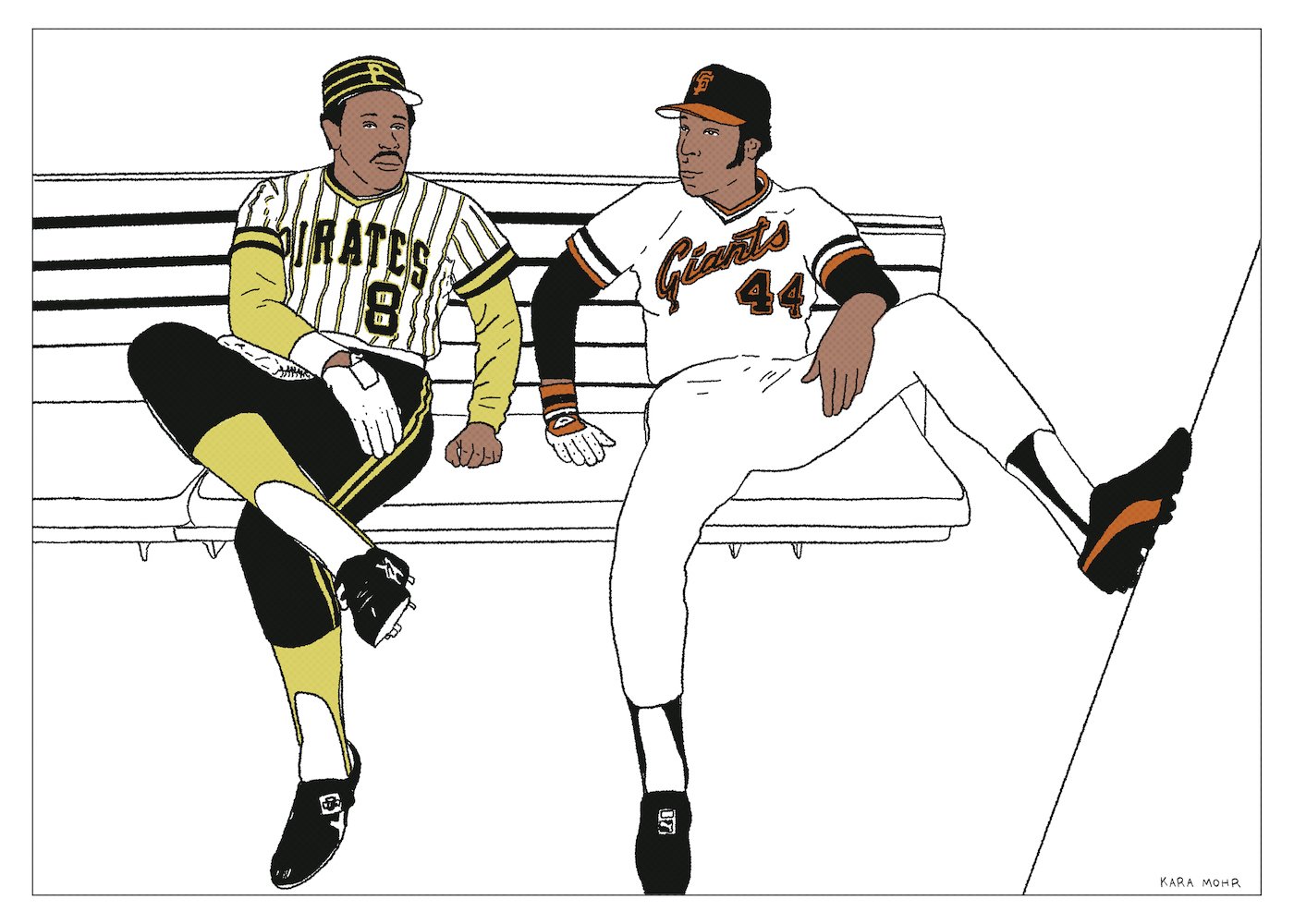

Willie McCovey and Willie Stargell “The Other Willies”

Beyond their shared first name and their doppelgänger stats, McCovey and Stargell co-represent an enduring Major League Baseball archetype: post-Jackie-and-Larry, post-Hank-and-Willie MLB stars. Stretch and Pops were MVP, Hall of Fame sluggers young enough to appreciate the monumental importance of their predecessors and old enough to recall the ugliness of baseball’s recent past. The two Willies respectfully thrived so that Curt Flood could brazenly protest. They demurred so their superstar teammates—Mays and Clemente—could shine. If Willie Mays was always the untouchable standard, McCovey and Stargell—together—represented the enduring greatness of goodness.

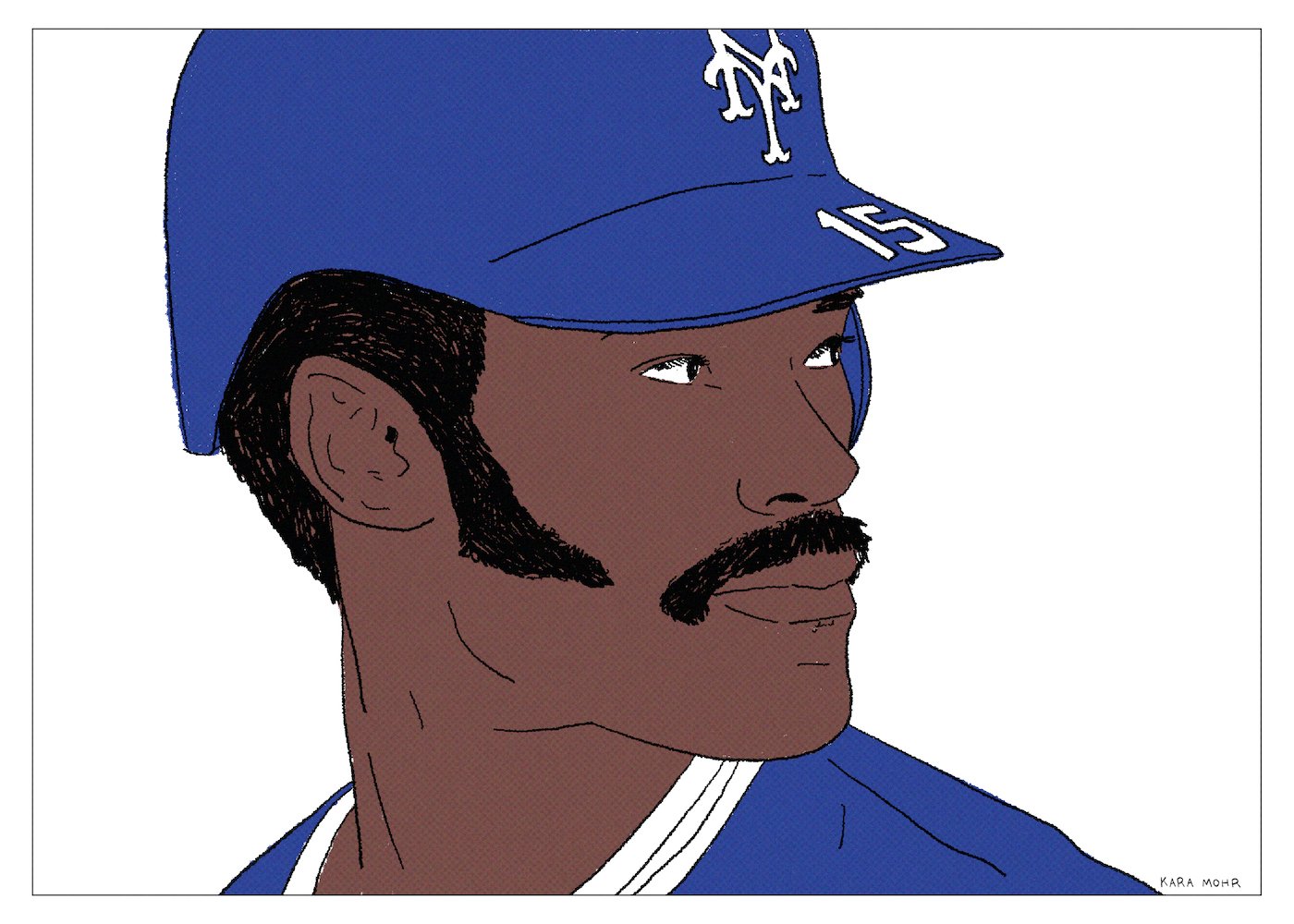

George Foster “Yahtzee!”

While some “Hall of Very Good” players have enjoyed extended, Cooperstown-caliber runs—Wally Berger, Hal Trosky and Mo Vaughn come to mind—the actual number is smaller than you’d think. George Foster might belong in that class except that—unlike most others, whose careers were cut short by injury, military service or poor self care—he avoided injuries, fought in no wars and took immaculate care of himself. Moreover, his peak was matched only by the mediocrity of what came before and after. Many people have suggested that George Foster was a great “what if” story—what if he’d been given a chance to start earlier in his career with The Giants? What if The Mets had protection for Foster in their early Eighties lineups. Alternately, Foster might also be one of the game’s great “what if not” stories—what would his career have looked like had he not played for The Big Red Machine?

Dave Kingman “Kong”

Dave Kingman’s entire career—but especially his 1977 season, wherein he played his way off four different teams—suggests a dour, underperforming athlete who soiled each nest he landed in. However, beneath the surface of that framing is very different and equally viable narrative: Kong was rushed and forsaken—over and over again. He was a grown man—a superstar—every fifteen times at the plate and a helpless child the other fourteen times. George Foster, Garry Maddox, Gary Matthews and Bobby Bonds—Kingman’s teammates on The Giants in the early Seventies—all struck out much more than they walked. But none of them could destroy baseballs quite like Dave Kingman. And as a result, they were given time to practice, fail, practice, fail less, practice and—eventually—succeed. But not Dave Kingman. Everybody is awed by King Kong. But nobody roots for him.

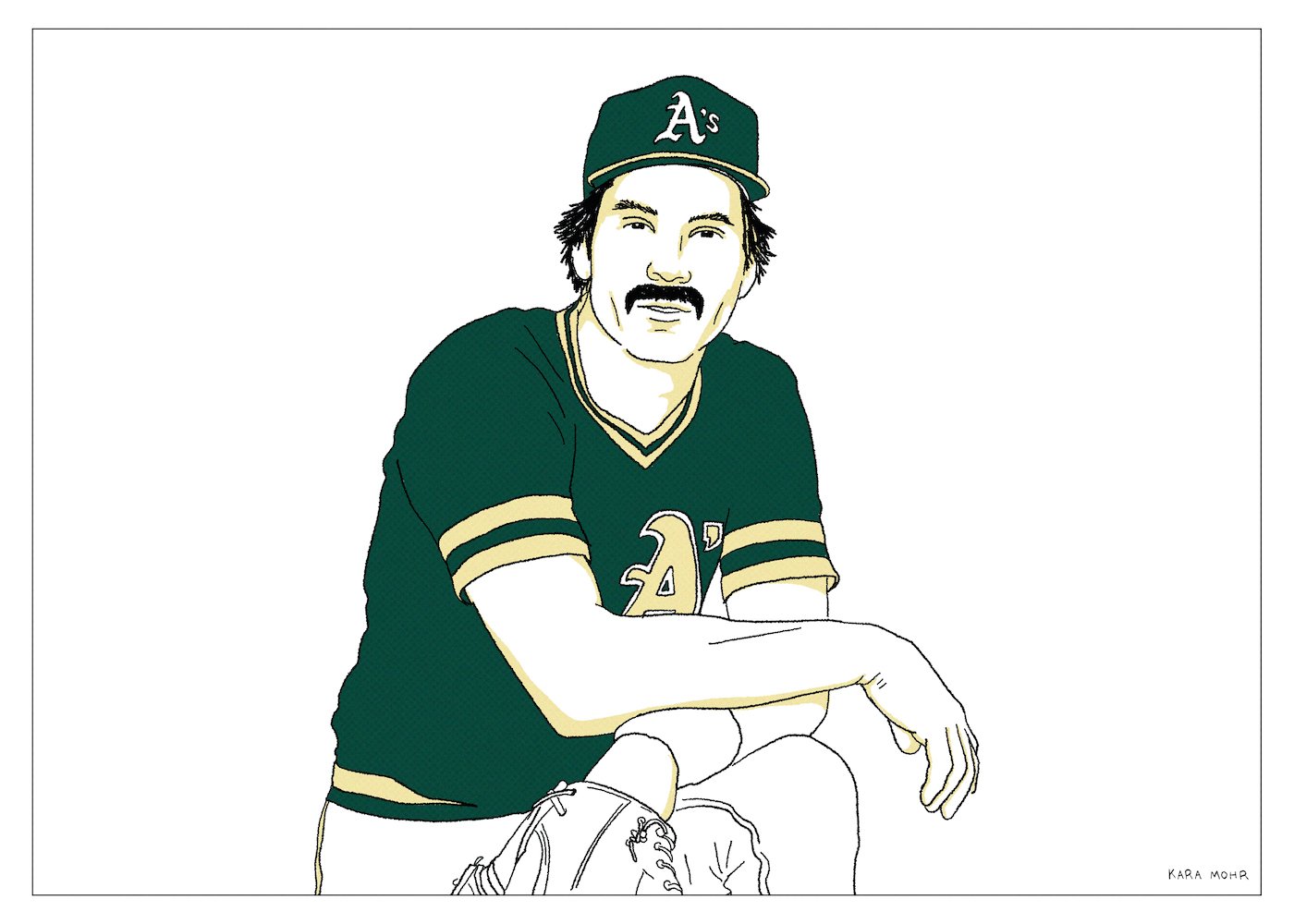

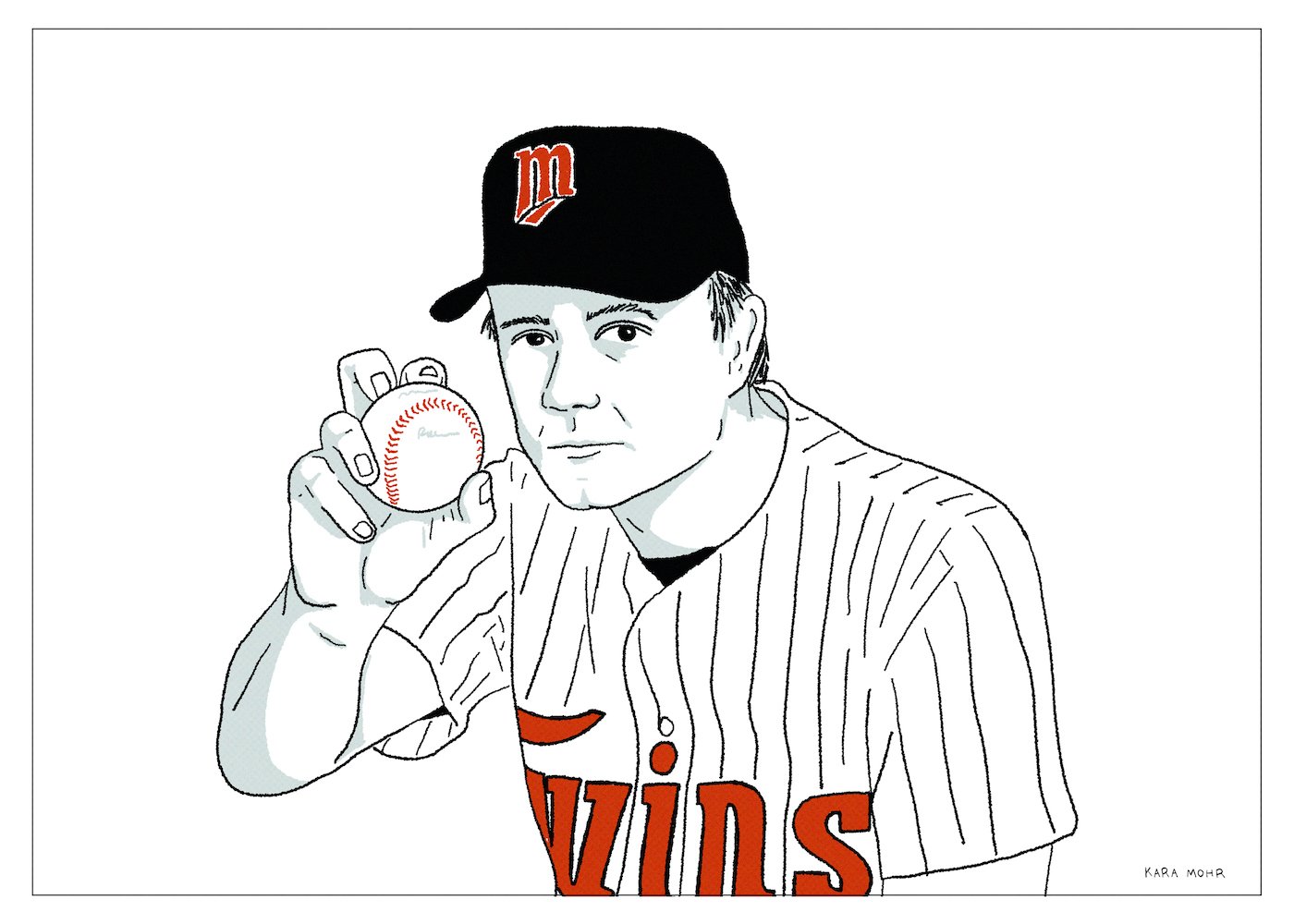

Joe Niekro “Do I Look Like a Doctor?”

For twenty plus seasons, and with the possible exception of Gaylord Perry, no pitcher doctored a baseball like Joe Niekro. Despite two decades of skirting the rules, though, Niekro was caught just once, in 1987 when he was tossed from a game by umpire Tim Tschida. Niekro’s ball doctoring was a long held, open secret that players, managers, umps and even fans were complicit in. But why? Why did we offer him such radical empathy? Perhaps because, in time, we all watch people around us become Joe Niekro. We ignore mild transgressions against nature in some sort of communal fight against aging. It’s only when it becomes too transgressive — when emery boards go flying or the third face lift becomes too difficult to look at — that we find our our collective, inner Tim Tschida and start moseying up to the mound.

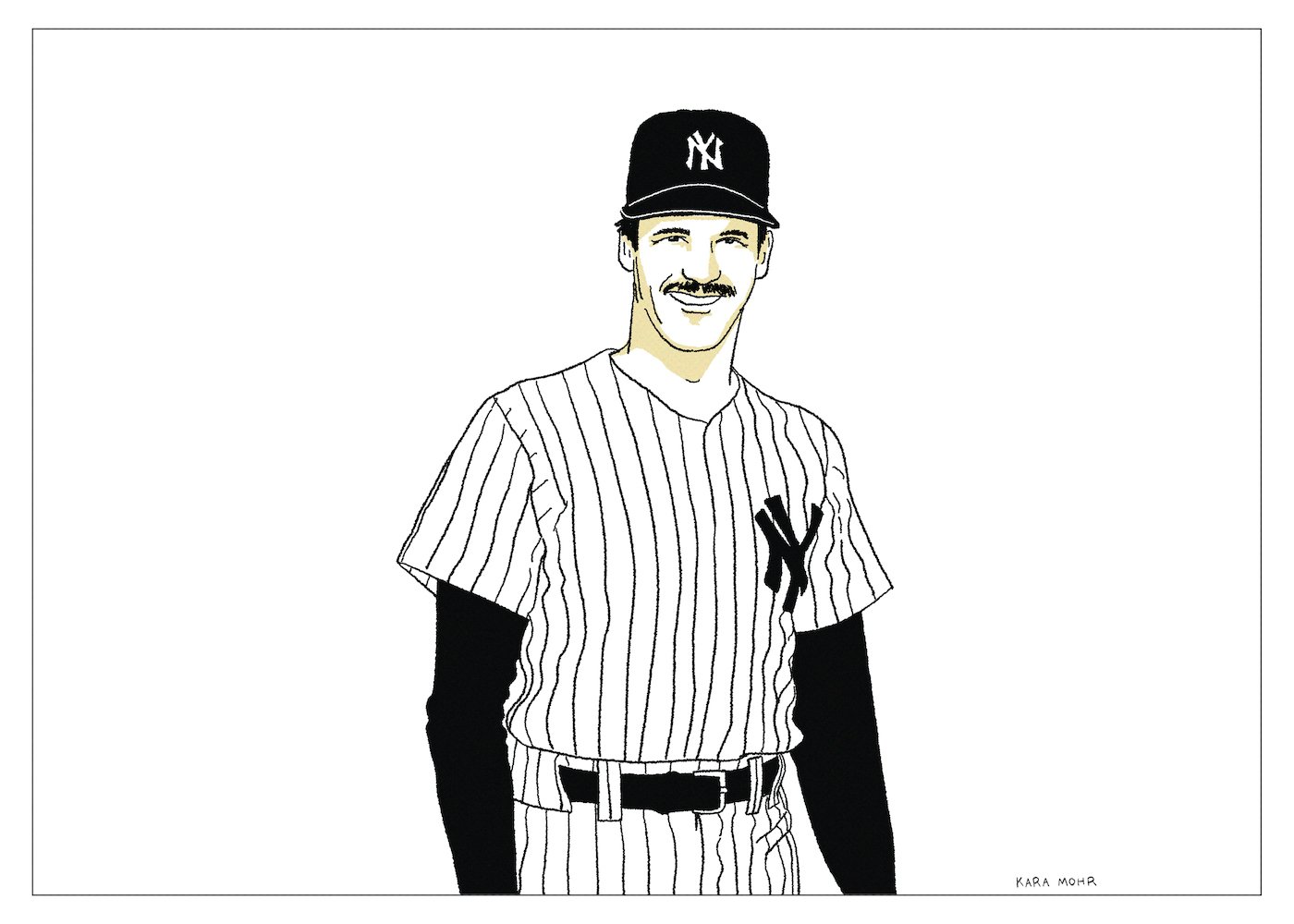

Ron Guidry “Gator Wrestling”

Sandy Koufax famously retired at the age of thirty, while still at the top of his game. To fans, his exit was abrupt, but graceful — the definition of an athlete leaving on his own terms. Ron Guidry was the opposite. While his career stats were almost interchangeable with Koufax’s, and while their peaks were similarly untouchable, their retirements were a study in contrast. After a stellar ‘85 season, wherein he won twenty-two games, led the league in winning percentage and finished second in the Cy Young award, Guidry faded. Injuries started to mount. Shoulder. Then elbow. Surgery was required. Rehabs were long. Every step forward felt like two steps back. Until, eventually, Gator was down in AAA, waiting for the call and wondering if he’d ever pitch in the majors again.

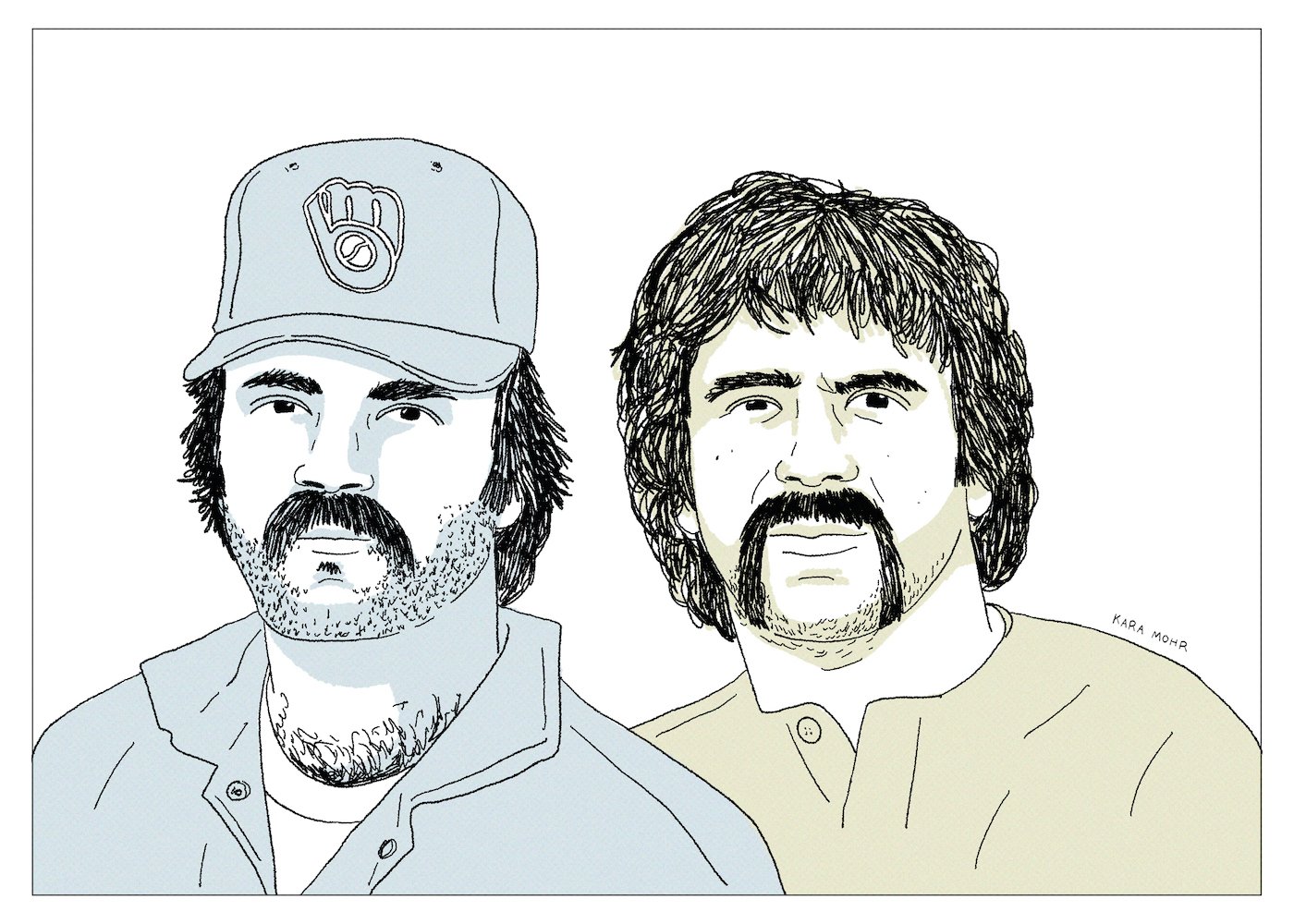

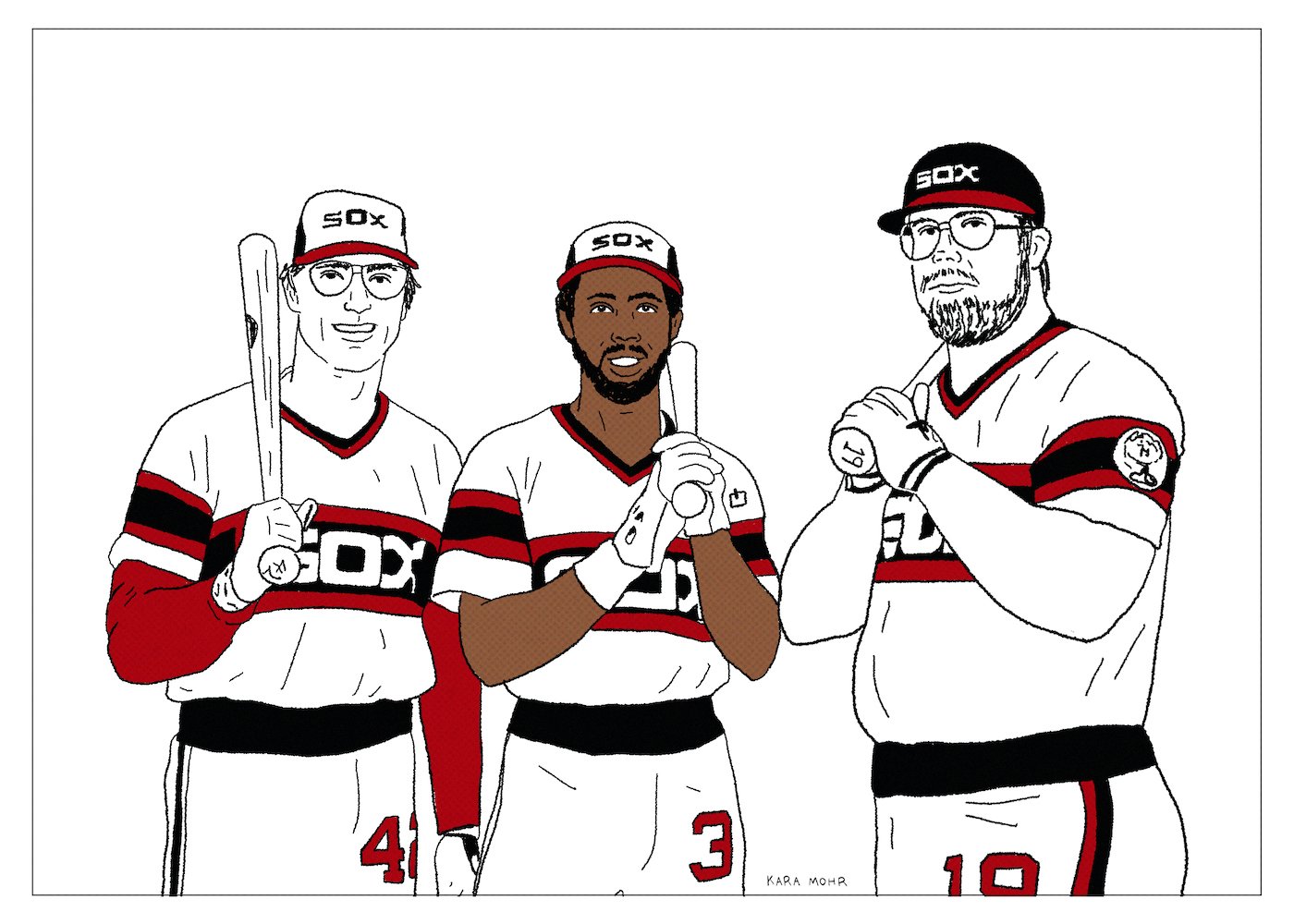

Gorman Thomas and Pete Vuckovich “Stormin’ & Vuke’s”

By the time Pete Vuckovich arrived to Milwaukee in 1981, Stormin’ Gorman Thomas was already a local folk hero. An average day at the office for Thomas featured three strikeouts, a long home run, and maybe a walk, followed by a couple dozen beers in the parking lot. The Brewers had been bottom dwellers when he first came up. But, by 1979, they were competing for titles. And by ‘81, with their potent lineup fully assembled, they found themselves one starting pitcher away from greatness. That ace arrived in the massive form of Pete Vuckovich, who played John C. Reilly to Thomas’ Will Ferrell. For two seasons, the stepbrothers made a run at greatness while setting into motion their future plans as owners of “Stormin’ & Vuke’s,” the greatest bar in the history of Wisconsin.

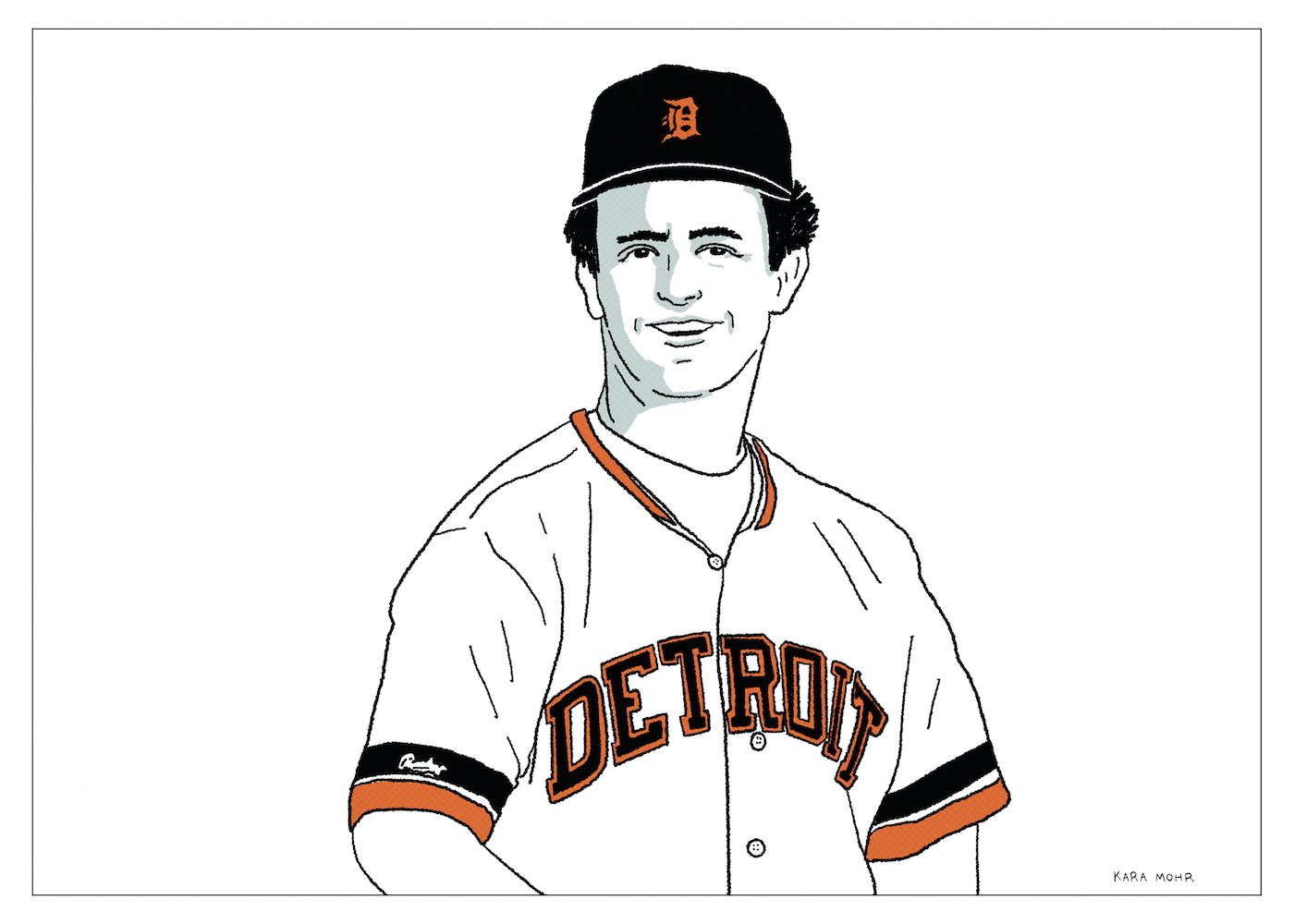

Fred Lynn “Gold Dust”

Five decades after Fred Lynn exploded onto the scene, Carlton Fisk’s Game Six game winner is baseball canon. Similarly, most middle-aged Bostonians still remember Yaz’s Triple Crown and Rice’s “monstah bombs ovah the green monstah.” However, casual fans have forgotten what Fred Lynn meant to Boston — the Gold Gloves, the Rookie of the Year and the MVP award, and the promise of a long, bright future. Throughout his twenties, Fred Lynn was racing towards Cooperstown. But as the years passed, as his injuries mounted, and as his jaw-dropping exploits faded into the rear view, many have forgotten what was once so exceptionally exceptional about Fred Lynn.

Steve Carlton “Lefty Loosey”

Between 1967 and 1984, the first full eighteen seasons of his career, Steve Carlton won three hundred and ten games and struck out nearly four thousand batters with basically two pitches — an elite fastball and a slider that was almost as blazing, but doubly devastating. At six foot four, Lefty towered over every opposing hitter, except for The Daves (Parker and Kingman). While his height and velocity were certainly intimidating, though, Carlton’s most unnerving feature was his unshakeable dispassion. He did not care who was at bat. He did not care what the score was. The batter was invisible to him. On the other hand, it’s not as though he was unconcerned with performance and craft. To the contrary, Lefty was obsessed with both. His training, while unorthodox, was meticulous. He meditated for hours on end. He practiced martial arts every day for years. He focused on flexibility and lean muscle and control. But, more than anything, he tried to focus on nothing at all.

Steve Garvey “Mr. Clean”

He was considered the surest of sure bets — as American as apple pie, as handsome as any movie star and as natural as Roy Hobbs. Steve Garvey was the clean living, god loving, good looking MVP at the heart of The Dodgers batting order. But also, his appeal went far beyond his All-Star performance on the field. He was “Captain America.” Square jaw. Not a hair out of place. Biceps and forearms that resembled spinached-up Popeye. And, what’s more, he was married to Barbie! Steve and Cyndy Garvey were Hollywood’s heroes during Reagan’s “Morning in America.” Until, once day, things got bad. And then worse. And then much worse. Until those nicknames became ironic chuckles. Until Steve Garvey became a reminder that the only thing America likes more than a rags to riches story is a riches to rags story.

Graig Nettles “Vigilante”

First off, his name is Graig. G-R-A-I-G. It’s not Greg or Gregory. And it’s not Craig. Graig, with two G’s has more teeth than Greg or Craig. Graig looks possibly Welsh or Gaelic and like it wants to have more than one syllable. It’s a name that has caused confusion for decades, spawning baseball card typos and debates among young Yankee fans back in the day. And yet, in spite of its oddness, there’s no other name that would have worked. Of the twenty plus thousand people to have played major league baseball, only one is named Graig. Moreover, etymology suggests that “Graig” roughly means “vigilant.” And while Graig Nettles was many things on the field — an elite fielder and a perennial home run threat — and many more things off the field — a brawler, a rule bender, and a loyal teammate — he was absolutely nothing if not vigilant.

Greg Luzinski “The Bull”

Baseball has provided us with a handful of quirky, if semi-validating, proof points for the theory of “nominative determinism” — the idea that a person’s name somehow determines their livelihoods. There’s Cecil and Prince “Fielder” (neither of whom were known for their gloves). “Homer” Bailey and “Homer” Bush (the former a pitcher, the latter not exactly a slugger). Maybe Rollie “Fingers” qualifies (admittedly a stretch)? How about Grant “Balfour” (ball four)? Those rare examples are all well and good, but also confirm that ballplayers are personified less by their names than by their nicknames. “Charlie Hustle.” “Hammerin’ Hank.” “Steady Eddie.” These, much more so than first or last names, predicted the destinies of their owners. However, in the roughly one hundred and fifty years of professional baseball, no nickname has better suited its player than Greg “The Bull” Luzinski — a colossal man, put on this earth to annihilate baseballs and, one day, sling BBQ.

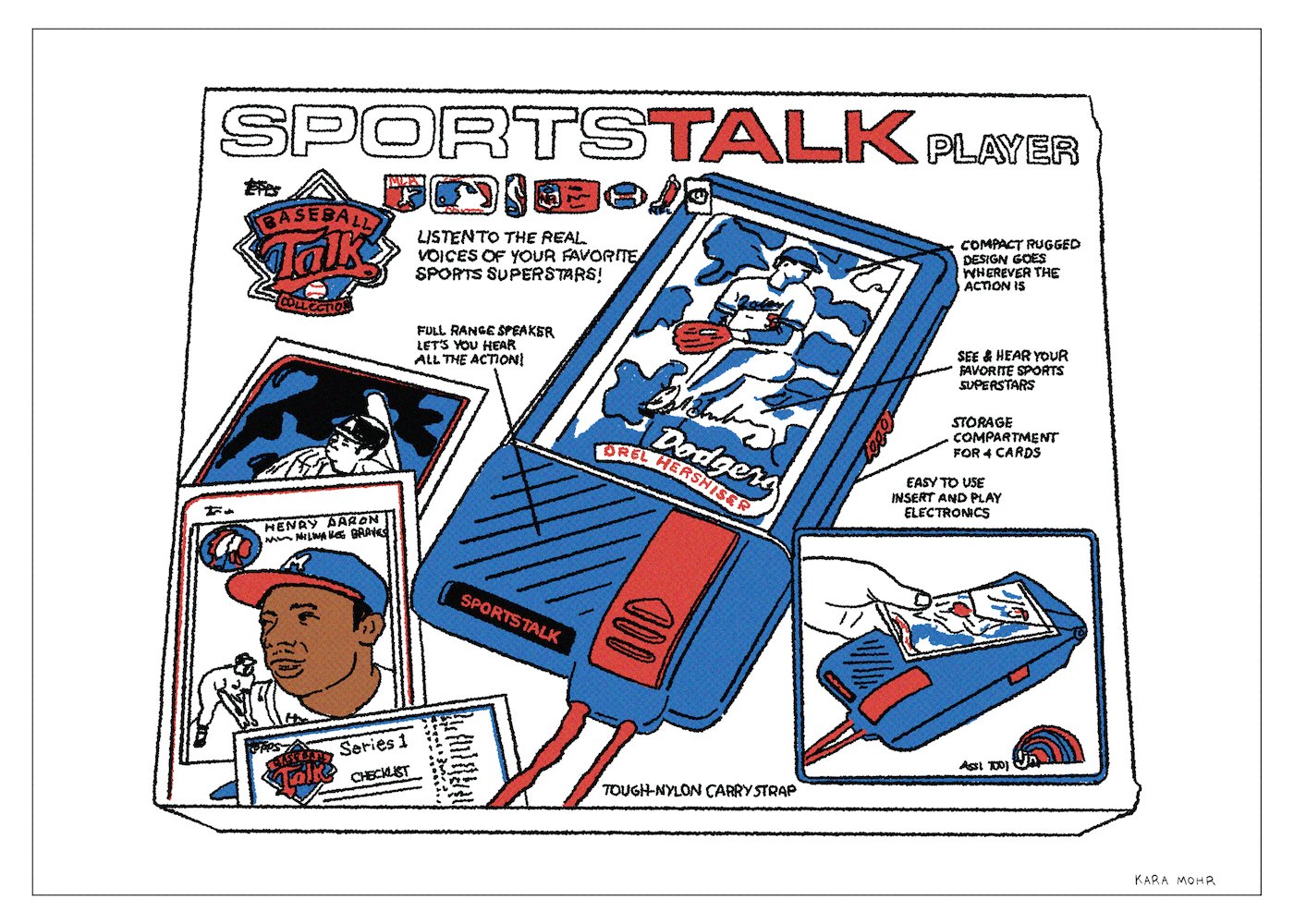

LJN Corporation “Topps Sports Talk Player”

First released in 1959, the Braun TP1 is a masterpiece. The phono-radio is considered by many to be a high water mark of twentieth century product design — its functionalism a complete validation of Dieter Rams’ “as little design as possible” ethos. Thirty years later the LJN toy company and Topps paid homage to Rams’ pièce de résistance with their Sports Talk player and Baseball Talk cards. The electronic player was actually a blue and red plastic portable phonograph and the cards resembled Topps’ bubblegum variety, except larger and with a miniature vinyl record pressed onto their backs. Like Rams’ TP1, the needle on the Sports Talk player sat beneath the records (cards). Like the TP1, the Sports Talk player was a feat of minimalist design and engineering. But unlike the TP1, the Sports Talk player was a piece of crap. Cheaply made. Easily damaged. Hard to explain and harder to understand. It lasted exactly one season and left behind a cautionary tale that fits somewhere between New Coke and “Ishtar.” For the record, though, I kind of dug New Coke. I thought “Ishtar” was pretty funny. And I freakin’ love my Sports Talk player.

Dave Parker “The Masked Cobra”

Jim Rice stood six feet, two inches tall and weighed two hundred pounds. At the plate in Fenway, he looked like the perfect slugger. But, next to Dave Parker, he looked like Rocky standing beside Drago. By the late Seventies, Pops Stargell was the same height as Rice, but with fifty pounds of excess gut. And yet, next to The Cobra, Stargell looked like Santa hanging out with The Incredible Hulk. Dave Parker was not the greatest player of his era, but for several seasons, he might have been the most important — and the most feared. On July 16 1978, two weeks after breaking his cheekbone in a home plate collision, The Cobra returned to the line-up wearing a very basic, but entirely frightening, half white, half black protective mask designed for hockey goalies. As he made his run towards a batting crown and the MVP award, Parker looked not unlike Jason Voorhees dressed as a giant killer bee.