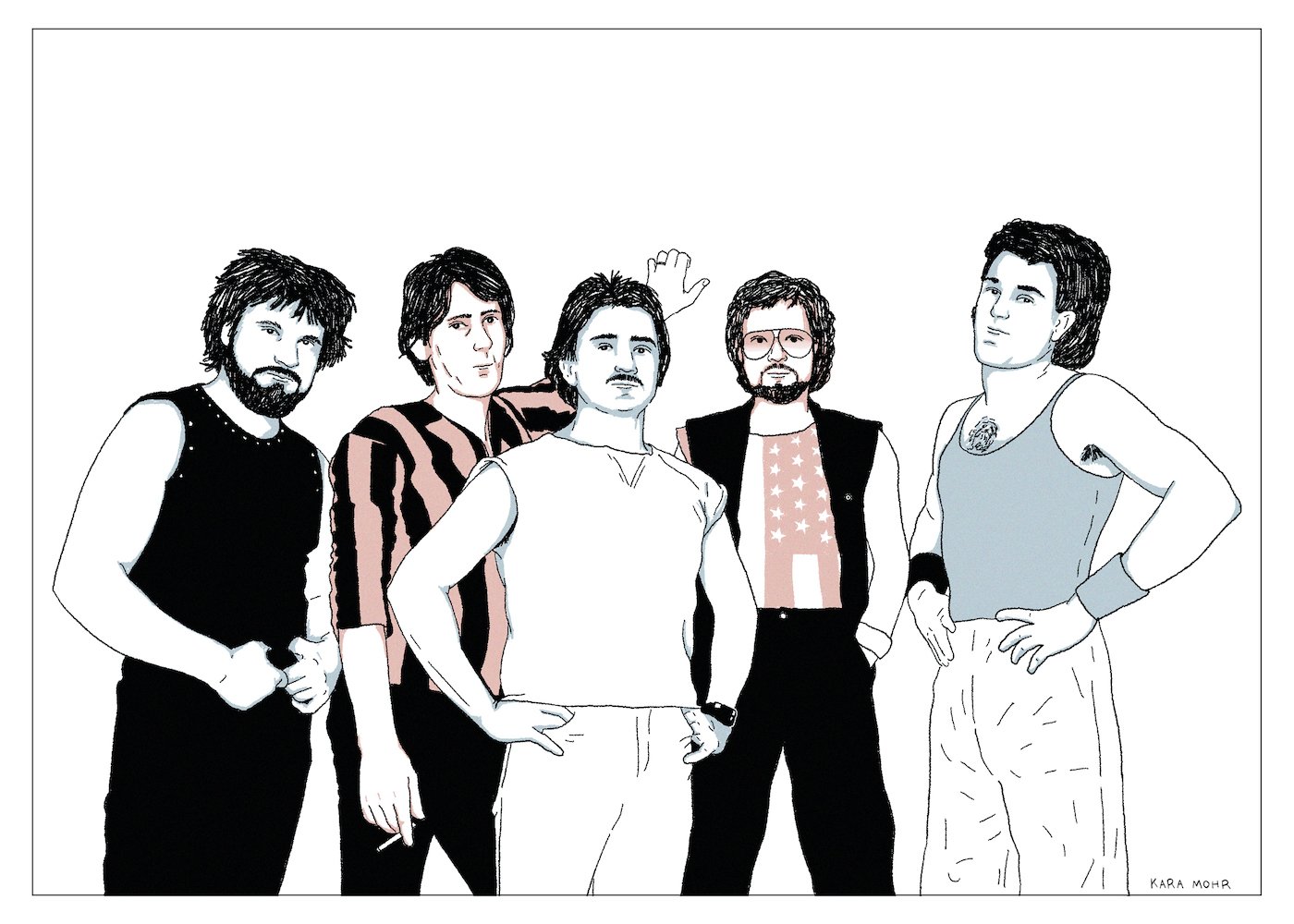

Blue Öyster Cult “Imaginos”

“Imaginos” is not really a Blue Öyster Cult album. Yes — it features the same five men who played on their beloved Seventies albums. But no — those five men did not write, play or record the album together. The name “Blue Öyster Cult” appears in name only, as a last ditch effort to see if the parties involved could recoup any of the significant cost sunk by their former drummer, Albert Bouchard. And yet, in a strange way, “Imaginos” is also the most Blue Öyster Cult album in that it was born from the band’s source material. While frequently indecipherable, “Imaginos” is oddly important in that its concept not only predated Blue Öyster Cult, but actually invented Blue Öyster Cult.

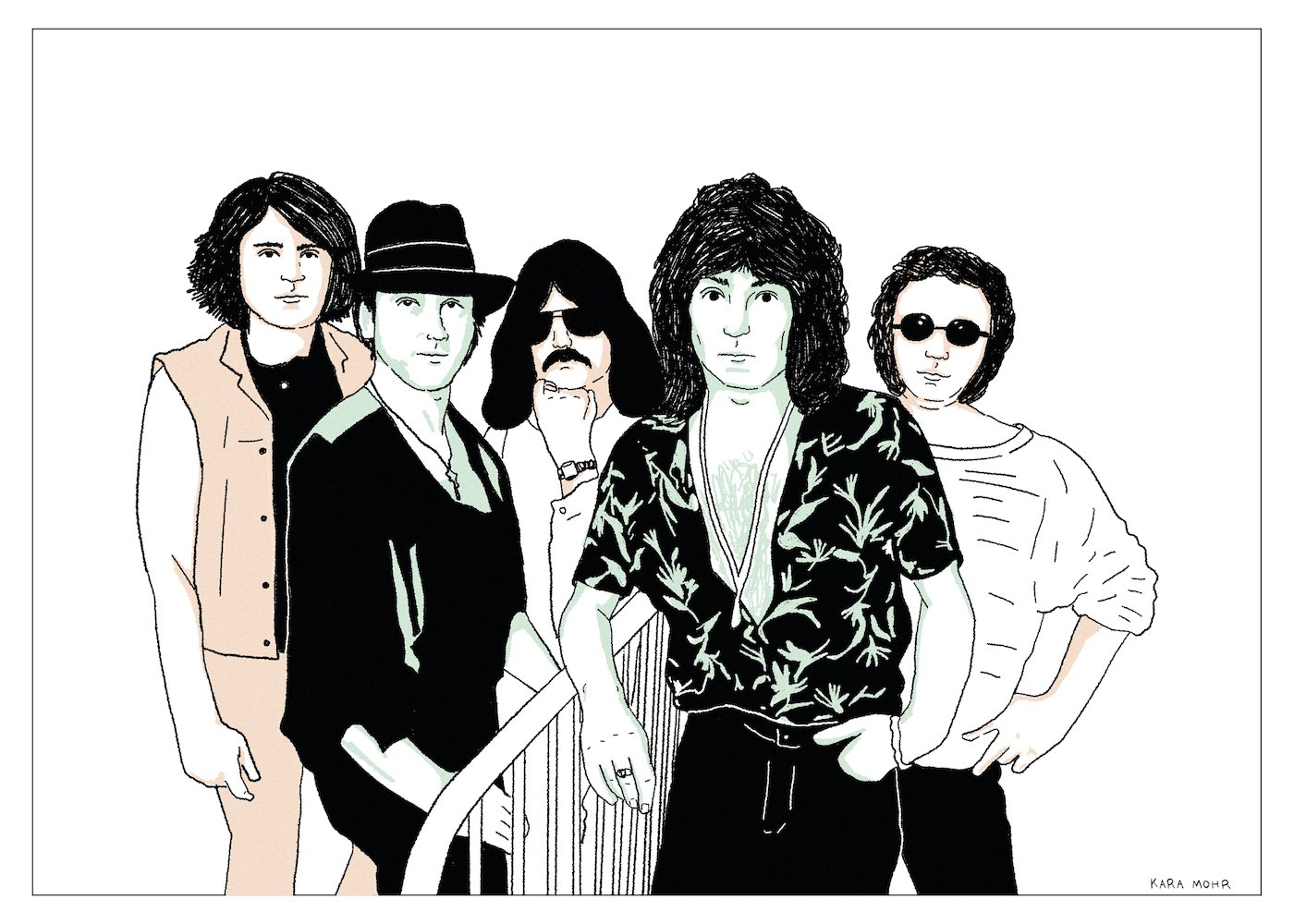

Deep Purple “The House of Blue Light”

In “This is Spinal Tap,” documentarian Marty Di Bergi reminds the band that their 1980 album “Shark Sandwich” had once famously received a review which read simply: “Shit Sandwich.” But in (cinematic) fact Spinal Tap were always loathed by the critics and “Shark Sandwich,” which featured “Sex Farm” and “No Place Like Nowhere,” was actually something of a return to form. Like “Shark Sandwich,” Deep Purple’s “Perfect Strangers” did not fare well with the mainstream press. In 1985, Rolling Stone printed a two star review that read like a one star review. Nevertheless, and like Spinal Tap’s late career hit, “Perfect Strangers” thrived commercially. But, if “Perfect Strangers” was Deep Purple’s “Shark Sandwich,” it follows that “The House of Blue Light” was their “Smell the Glove,” an ill-fated document of disunion that revealed a band spiraling into mid-life crisis.

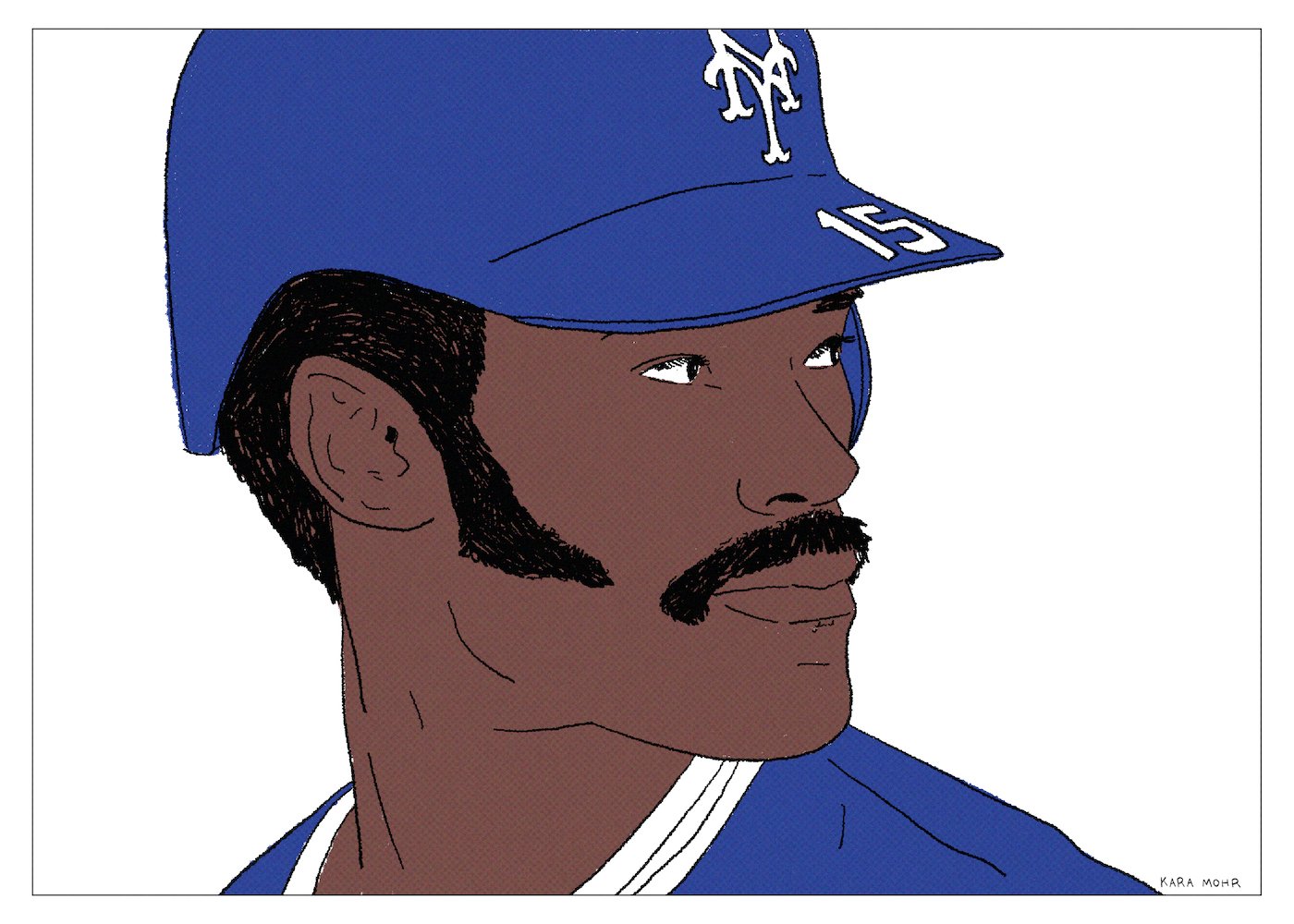

George Foster “Yahtzee!”

While some “Hall of Very Good” players have enjoyed extended, Cooperstown-caliber runs—Wally Berger, Hal Trosky and Mo Vaughn come to mind—the actual number is smaller than you’d think. George Foster might belong in that class except that—unlike most others, whose careers were cut short by injury, military service or poor self care—he avoided injuries, fought in no wars and took immaculate care of himself. Moreover, his peak was matched only by the mediocrity of what came before and after. Many people have suggested that George Foster was a great “what if” story—what if he’d been given a chance to start earlier in his career with The Giants? What if The Mets had protection for Foster in their early Eighties lineups. Alternately, Foster might also be one of the game’s great “what if not” stories—what would his career have looked like had he not played for The Big Red Machine?

Dave Kingman “Kong”

Dave Kingman’s entire career—but especially his 1977 season, wherein he played his way off four different teams—suggests a dour, underperforming athlete who soiled each nest he landed in. However, beneath the surface of that framing is very different and equally viable narrative: Kong was rushed and forsaken—over and over again. He was a grown man—a superstar—every fifteen times at the plate and a helpless child the other fourteen times. George Foster, Garry Maddox, Gary Matthews and Bobby Bonds—Kingman’s teammates on The Giants in the early Seventies—all struck out much more than they walked. But none of them could destroy baseballs quite like Dave Kingman. And as a result, they were given time to practice, fail, practice, fail less, practice and—eventually—succeed. But not Dave Kingman. Everybody is awed by King Kong. But nobody roots for him.

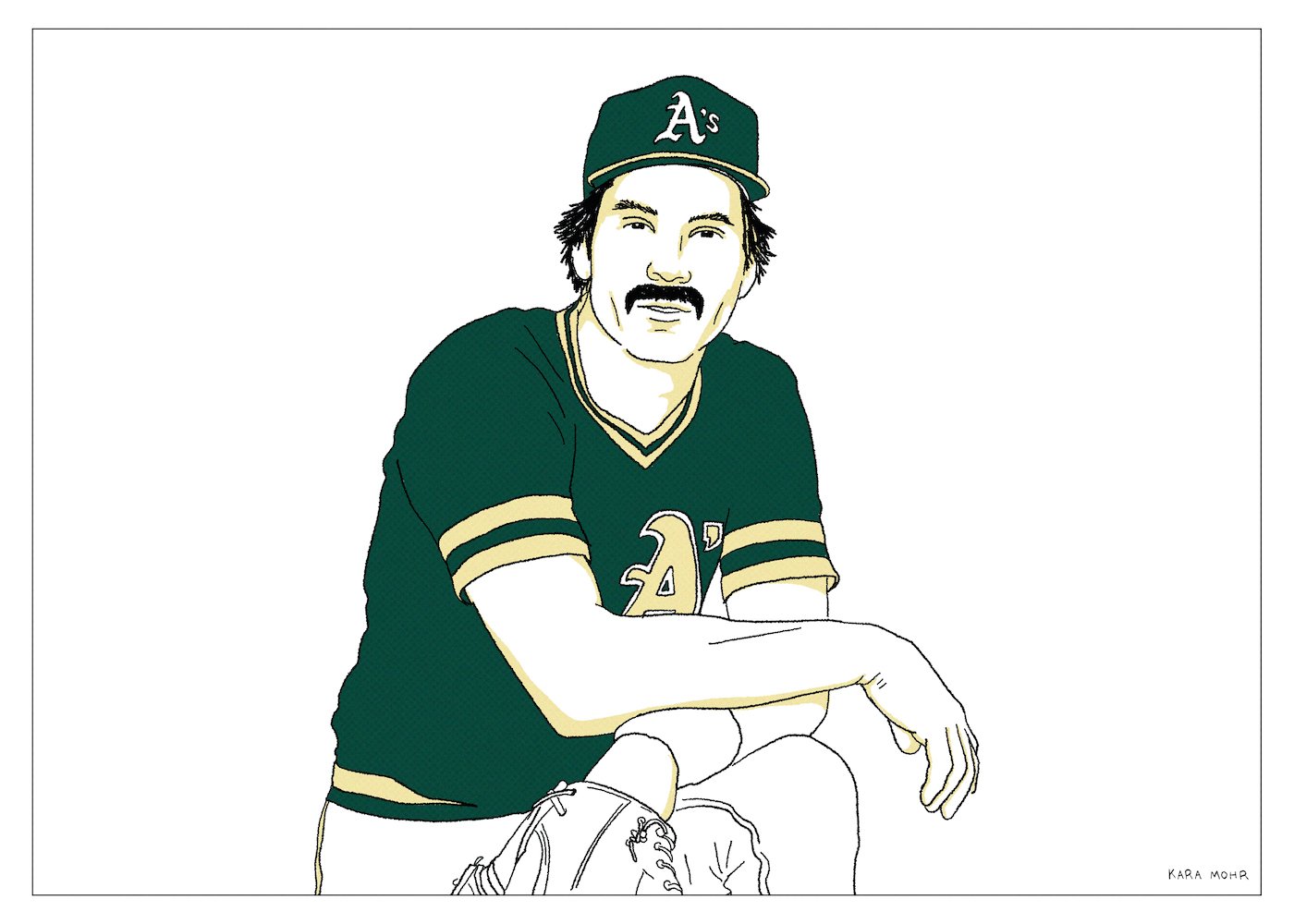

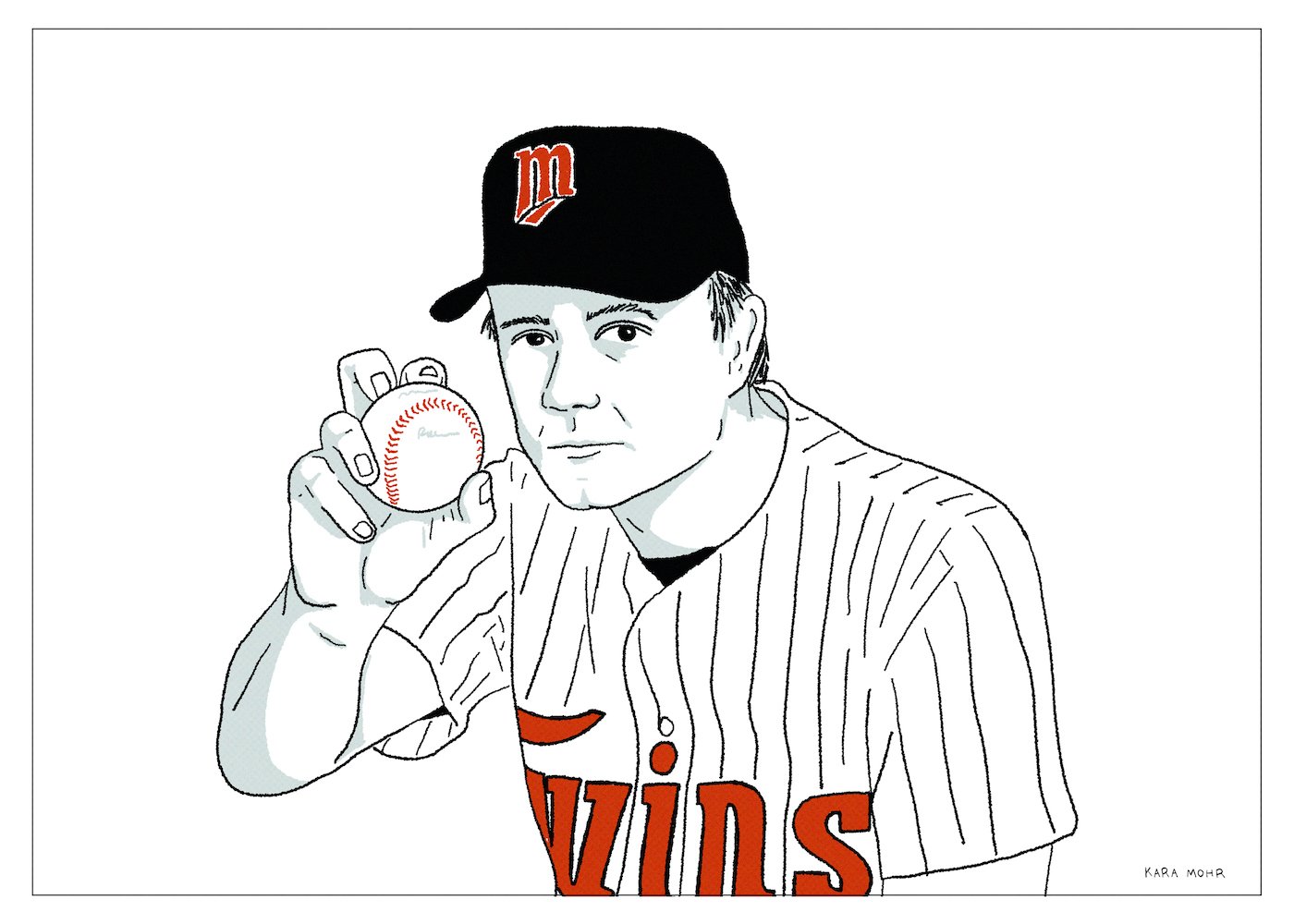

Joe Niekro “Do I Look Like a Doctor?”

For twenty plus seasons, and with the possible exception of Gaylord Perry, no pitcher doctored a baseball like Joe Niekro. Despite two decades of skirting the rules, though, Niekro was caught just once, in 1987 when he was tossed from a game by umpire Tim Tschida. Niekro’s ball doctoring was a long held, open secret that players, managers, umps and even fans were complicit in. But why? Why did we offer him such radical empathy? Perhaps because, in time, we all watch people around us become Joe Niekro. We ignore mild transgressions against nature in some sort of communal fight against aging. It’s only when it becomes too transgressive — when emery boards go flying or the third face lift becomes too difficult to look at — that we find our our collective, inner Tim Tschida and start moseying up to the mound.

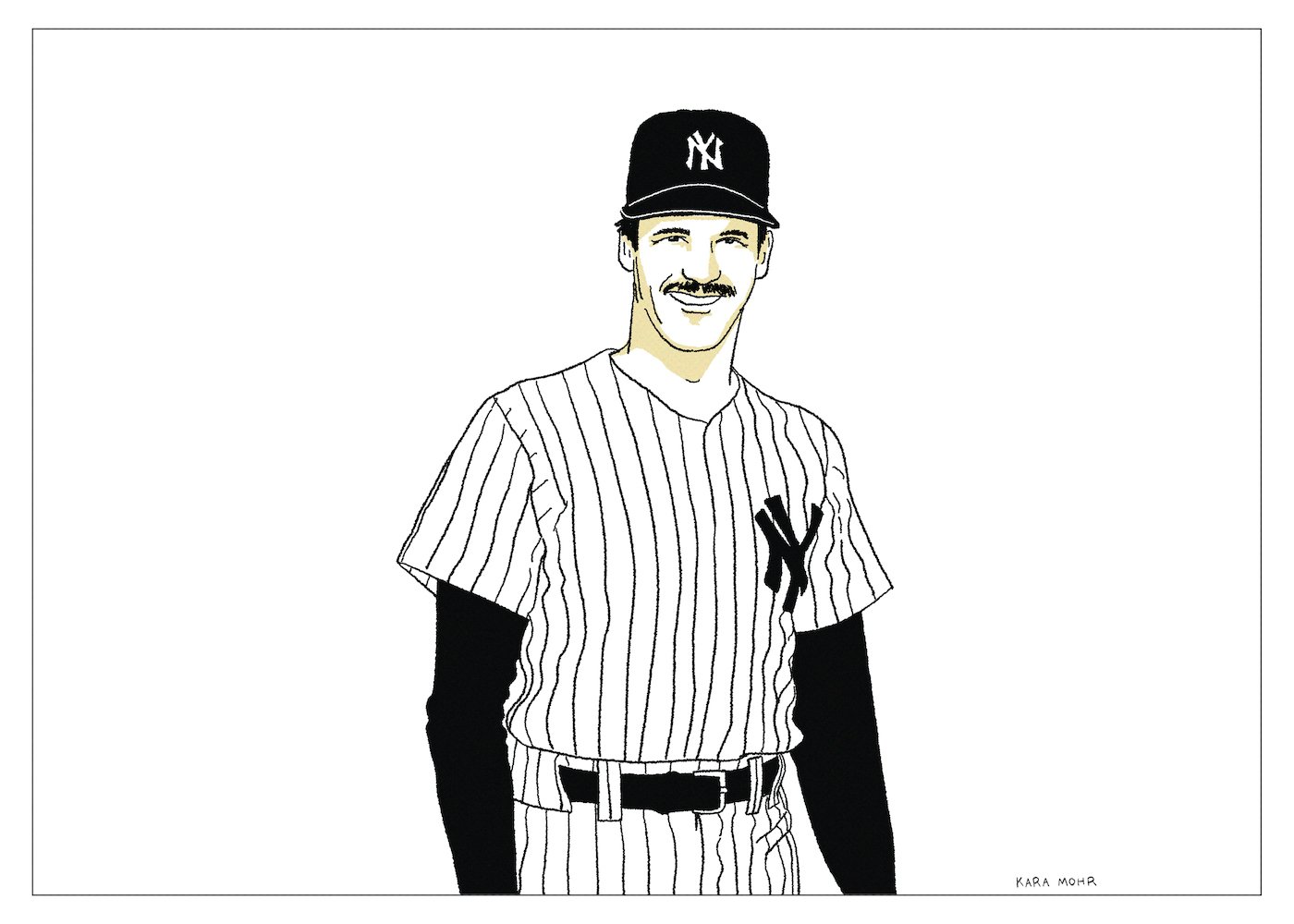

Ron Guidry “Gator Wrestling”

Sandy Koufax famously retired at the age of thirty, while still at the top of his game. To fans, his exit was abrupt, but graceful — the definition of an athlete leaving on his own terms. Ron Guidry was the opposite. While his career stats were almost interchangeable with Koufax’s, and while their peaks were similarly untouchable, their retirements were a study in contrast. After a stellar ‘85 season, wherein he won twenty-two games, led the league in winning percentage and finished second in the Cy Young award, Guidry faded. Injuries started to mount. Shoulder. Then elbow. Surgery was required. Rehabs were long. Every step forward felt like two steps back. Until, eventually, Gator was down in AAA, waiting for the call and wondering if he’d ever pitch in the majors again.

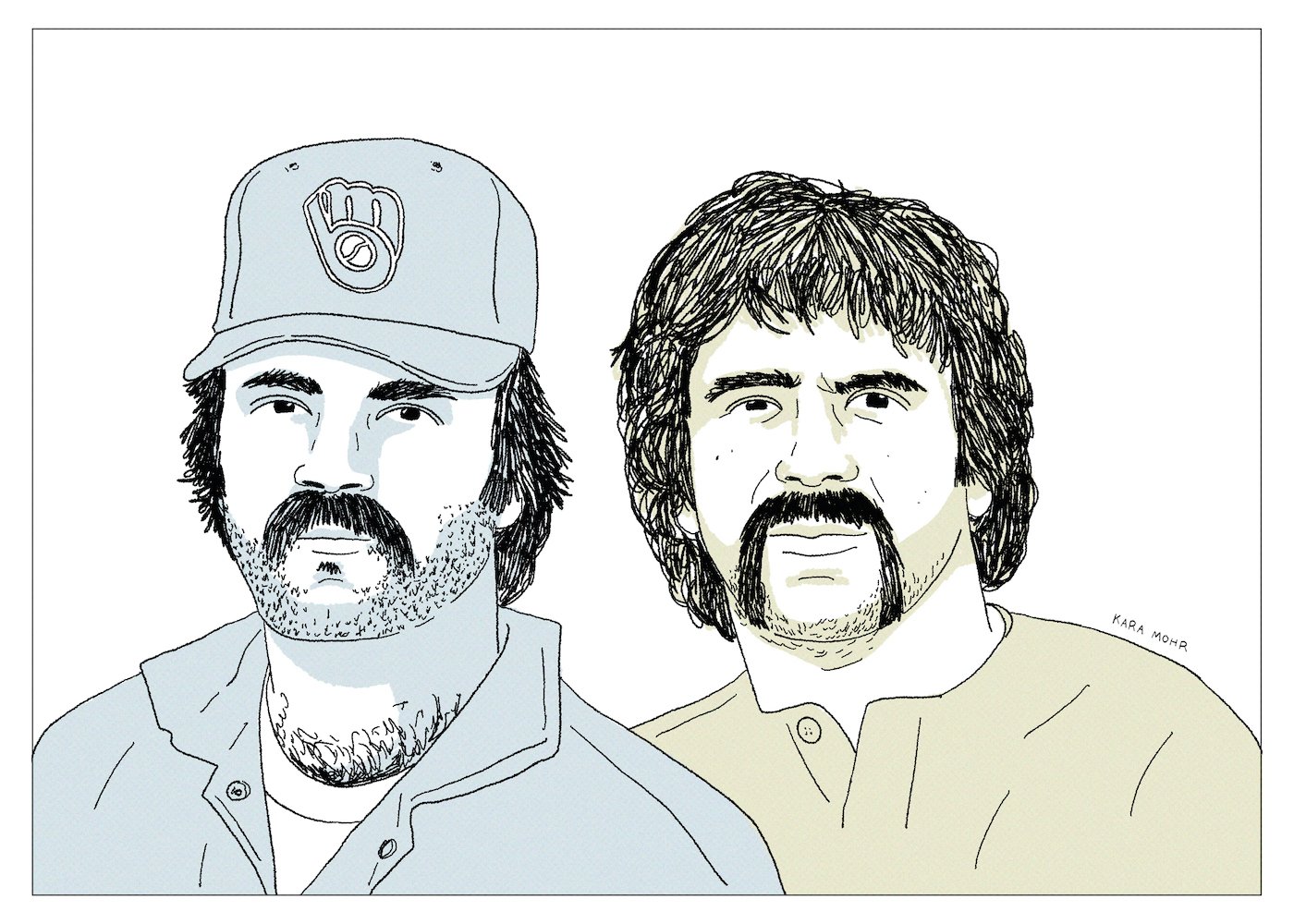

Gorman Thomas and Pete Vuckovich “Stormin’ & Vuke’s”

By the time Pete Vuckovich arrived to Milwaukee in 1981, Stormin’ Gorman Thomas was already a local folk hero. An average day at the office for Thomas featured three strikeouts, a long home run, and maybe a walk, followed by a couple dozen beers in the parking lot. The Brewers had been bottom dwellers when he first came up. But, by 1979, they were competing for titles. And by ‘81, with their potent lineup fully assembled, they found themselves one starting pitcher away from greatness. That ace arrived in the massive form of Pete Vuckovich, who played John C. Reilly to Thomas’ Will Ferrell. For two seasons, the stepbrothers made a run at greatness while setting into motion their future plans as owners of “Stormin’ & Vuke’s,” the greatest bar in the history of Wisconsin.

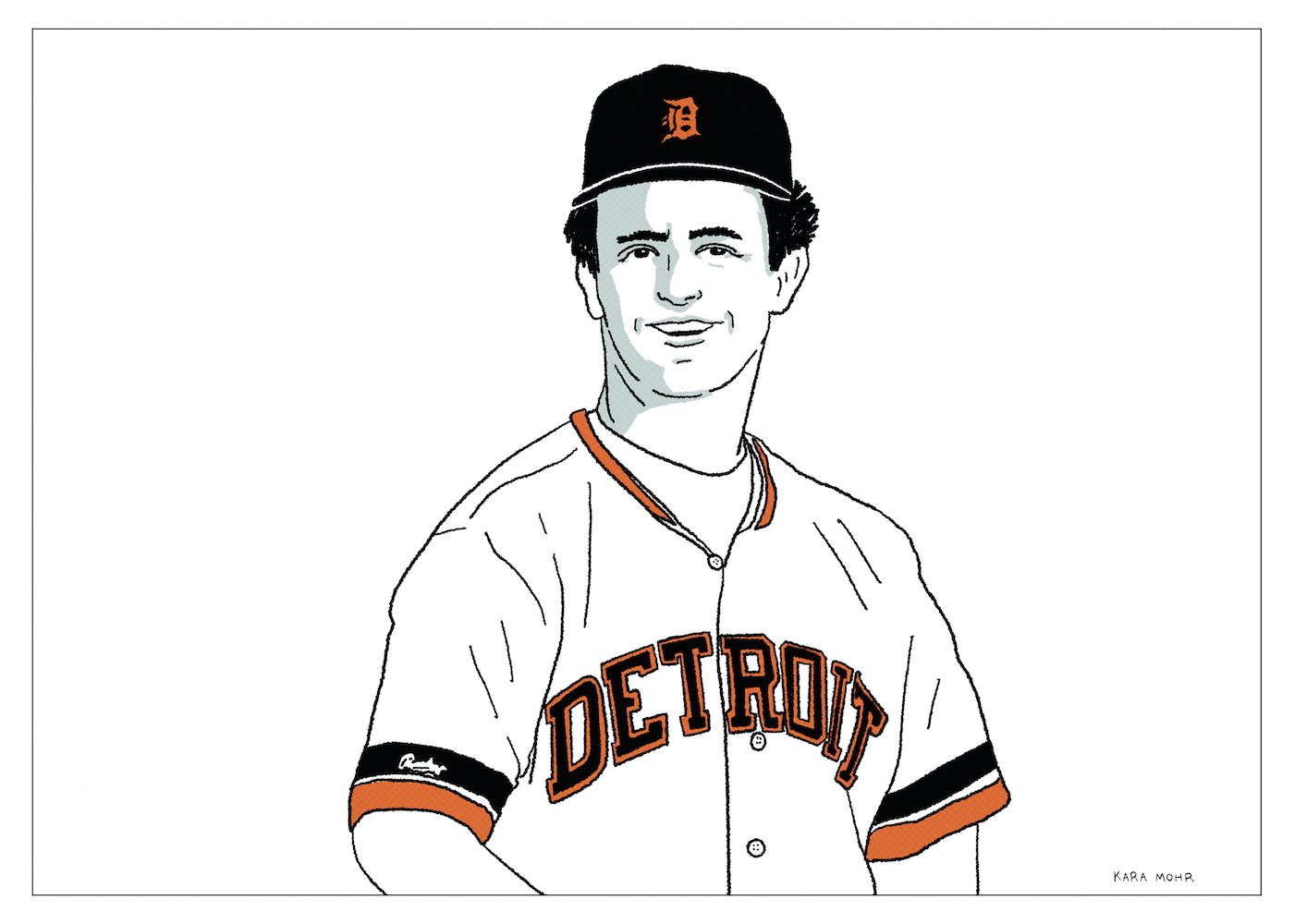

Fred Lynn “Gold Dust”

Five decades after Fred Lynn exploded onto the scene, Carlton Fisk’s Game Six game winner is baseball canon. Similarly, most middle-aged Bostonians still remember Yaz’s Triple Crown and Rice’s “monstah bombs ovah the green monstah.” However, casual fans have forgotten what Fred Lynn meant to Boston — the Gold Gloves, the Rookie of the Year and the MVP award, and the promise of a long, bright future. Throughout his twenties, Fred Lynn was racing towards Cooperstown. But as the years passed, as his injuries mounted, and as his jaw-dropping exploits faded into the rear view, many have forgotten what was once so exceptionally exceptional about Fred Lynn.

Steve Carlton “Lefty Loosey”

Between 1967 and 1984, the first full eighteen seasons of his career, Steve Carlton won three hundred and ten games and struck out nearly four thousand batters with basically two pitches — an elite fastball and a slider that was almost as blazing, but doubly devastating. At six foot four, Lefty towered over every opposing hitter, except for The Daves (Parker and Kingman). While his height and velocity were certainly intimidating, though, Carlton’s most unnerving feature was his unshakeable dispassion. He did not care who was at bat. He did not care what the score was. The batter was invisible to him. On the other hand, it’s not as though he was unconcerned with performance and craft. To the contrary, Lefty was obsessed with both. His training, while unorthodox, was meticulous. He meditated for hours on end. He practiced martial arts every day for years. He focused on flexibility and lean muscle and control. But, more than anything, he tried to focus on nothing at all.

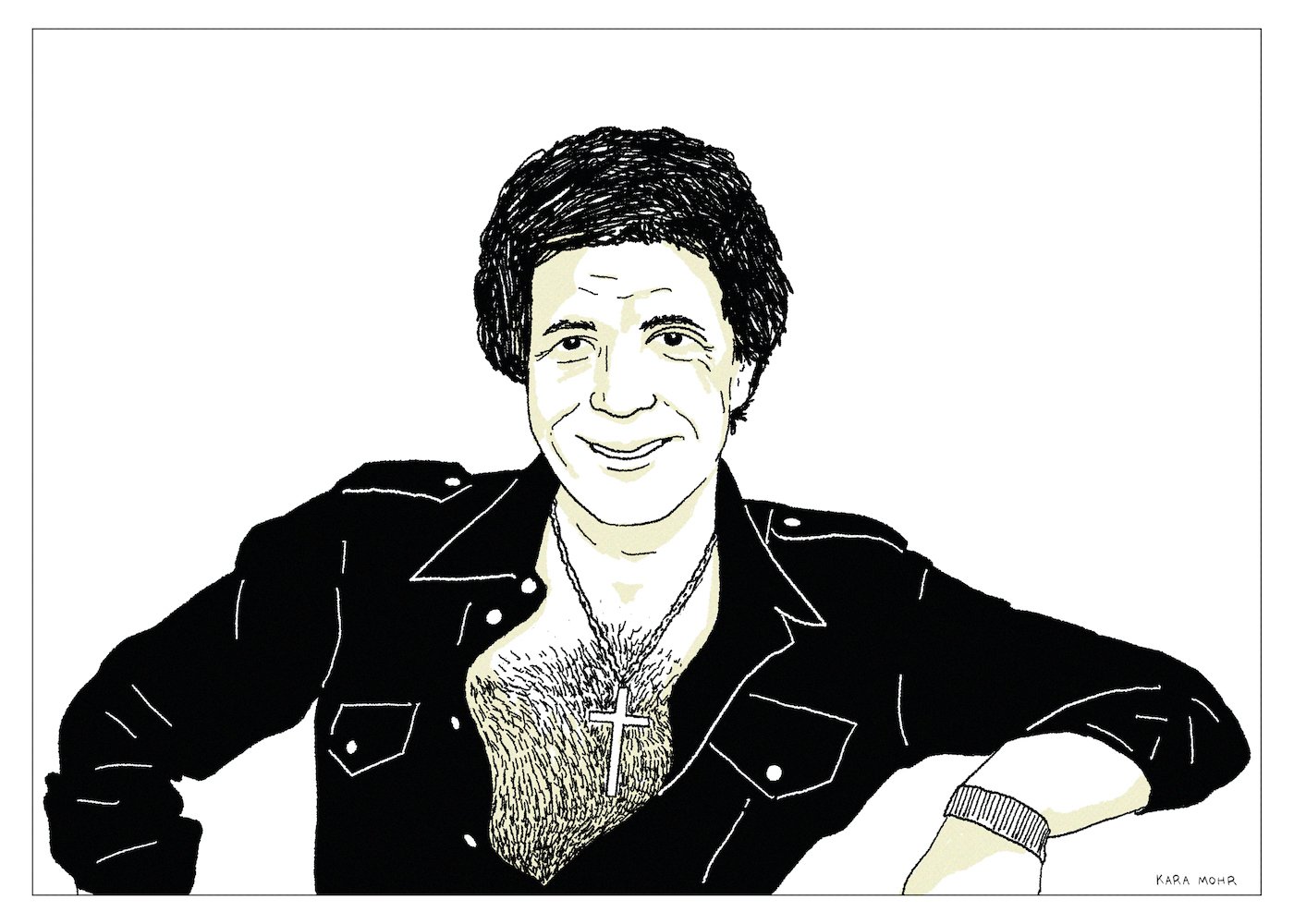

Tom Jones “Darlin’”

Like Cher, Tom Jones had a teeny tiny waist. And, like Cher, Jones loved to show some skin once upon a time. Both were unafraid of tight pants. Both hosted popular TV programs — “This is Tom Jones” (1969 through 1971) being a precursor to Sonny and Cher’s variety shows. Both had famous marriages (Jones’ for its mystery and longevity, Cher for its popularity) and perhaps more famous relationships outside of their marriages (Cher with Greg Allman, David Geffen and Gene Simmons and Jones with Mary Wells and, apparently, two hundred and fifty fans per year). Both are known for their iconic, husky voices, though neither is proficient on any instrument. But, more than anything else, the thing that bound Jones and Cher was the thing that happened when they put it all together — the voice, the body, the moves, the attitude, the screen presence, the sex appeal. It was their unfathomable “toomuchness.”

John Denver “It’s About Time”

Even before his divorce from Annie Martell, before the death of his father, and before his star had fully faded, John Denver’s music had begun to take a detour. At first, the turn was slow and gradual enough to be barely noticeable. But, by the early Eighties, he’d largely abandoned the acoustic jangle of his Folk and Country hits for something firmly Adult Contemporary. And by “Adult” I really mean something like music for children performed with a string section, and guitars and synths turned down so as not to disturb. And by “Contemporary” I really mean corny like late Seventies Margaritaville James Taylor or like Barry Manilow without the camp. That’s the sound of “It’s About Time,” an album of depressed ballads and worldly aspirations performed by one of the most overqualified bands ever assembled.

Steve Garvey “Mr. Clean”

He was considered the surest of sure bets — as American as apple pie, as handsome as any movie star and as natural as Roy Hobbs. Steve Garvey was the clean living, god loving, good looking MVP at the heart of The Dodgers batting order. But also, his appeal went far beyond his All-Star performance on the field. He was “Captain America.” Square jaw. Not a hair out of place. Biceps and forearms that resembled spinached-up Popeye. And, what’s more, he was married to Barbie! Steve and Cyndy Garvey were Hollywood’s heroes during Reagan’s “Morning in America.” Until, once day, things got bad. And then worse. And then much worse. Until those nicknames became ironic chuckles. Until Steve Garvey became a reminder that the only thing America likes more than a rags to riches story is a riches to rags story.

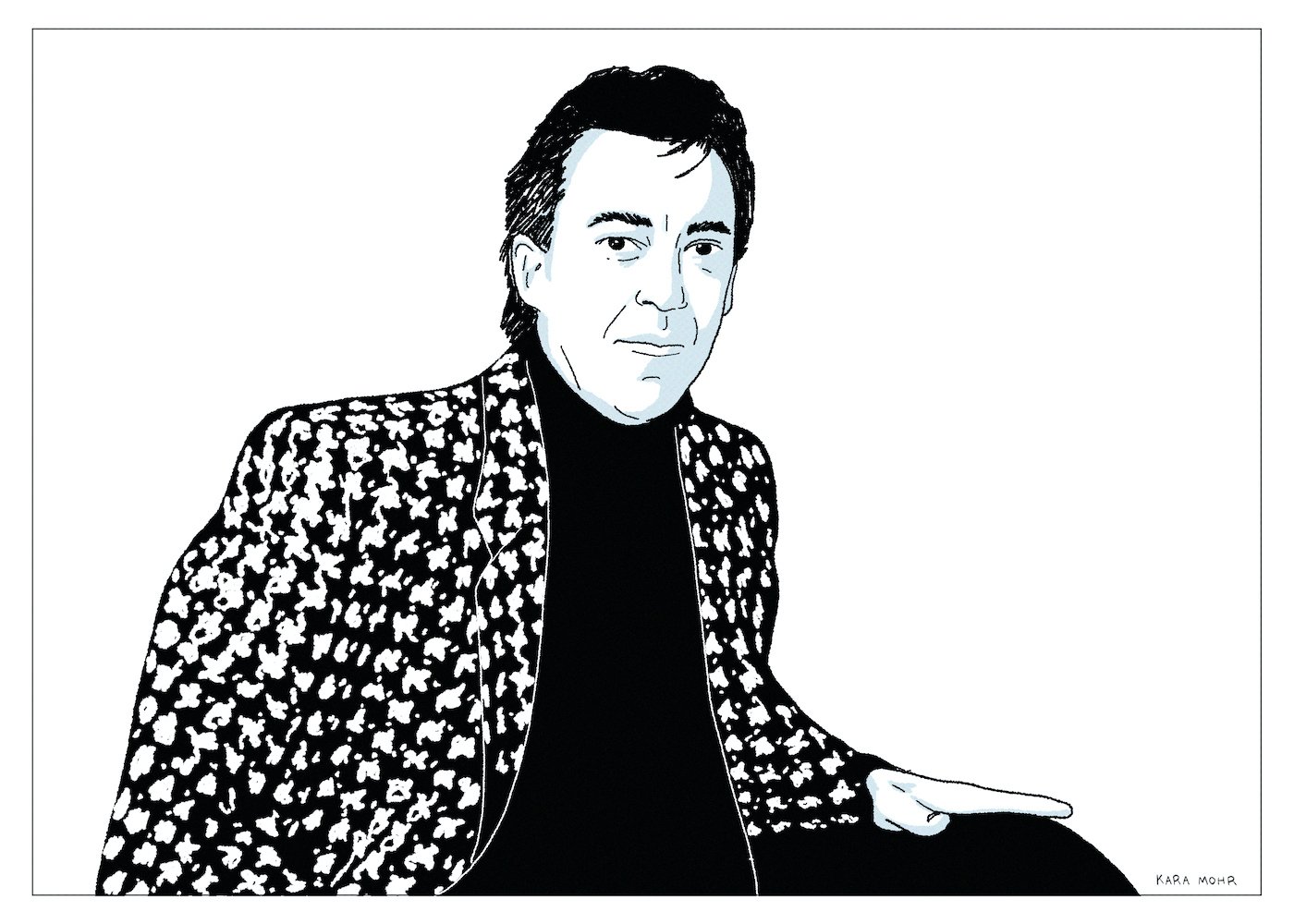

Boz Scaggs “Other Roads”

Though today he is known as a Steely Dan adjacent, dollar bin staple, Boz Scaggs is truly a man of many gifts. He possesses a soulful tenor, dipped in Van Morrison and glazed in Al Green. He has a knack for arrangements, for knowing when to let a song skate around and when to bring it back home. But his forte really seems to be some combination of a casual, Northern California vibe alongside the steely precision of his playing. Boz made music that might not thrill, but would almost always delight. It was music that thrived just in front of the background. There was really no one like Boz Scaggs. He was more successful than he was famous, though he was, for some time, also famous. He was also the kind of star who made the kind of music that could have only succeeded between 1976 and 1980. As a result, his celebrity was short lived. Once the calendar turned to 1981, Boz disappeared for seven long years. The guy that returned was less a Rock Star and more a Bay Area impresario. Well dressed. Wine curious. Affluent. Self-assured. Still totally casual and completely precise.

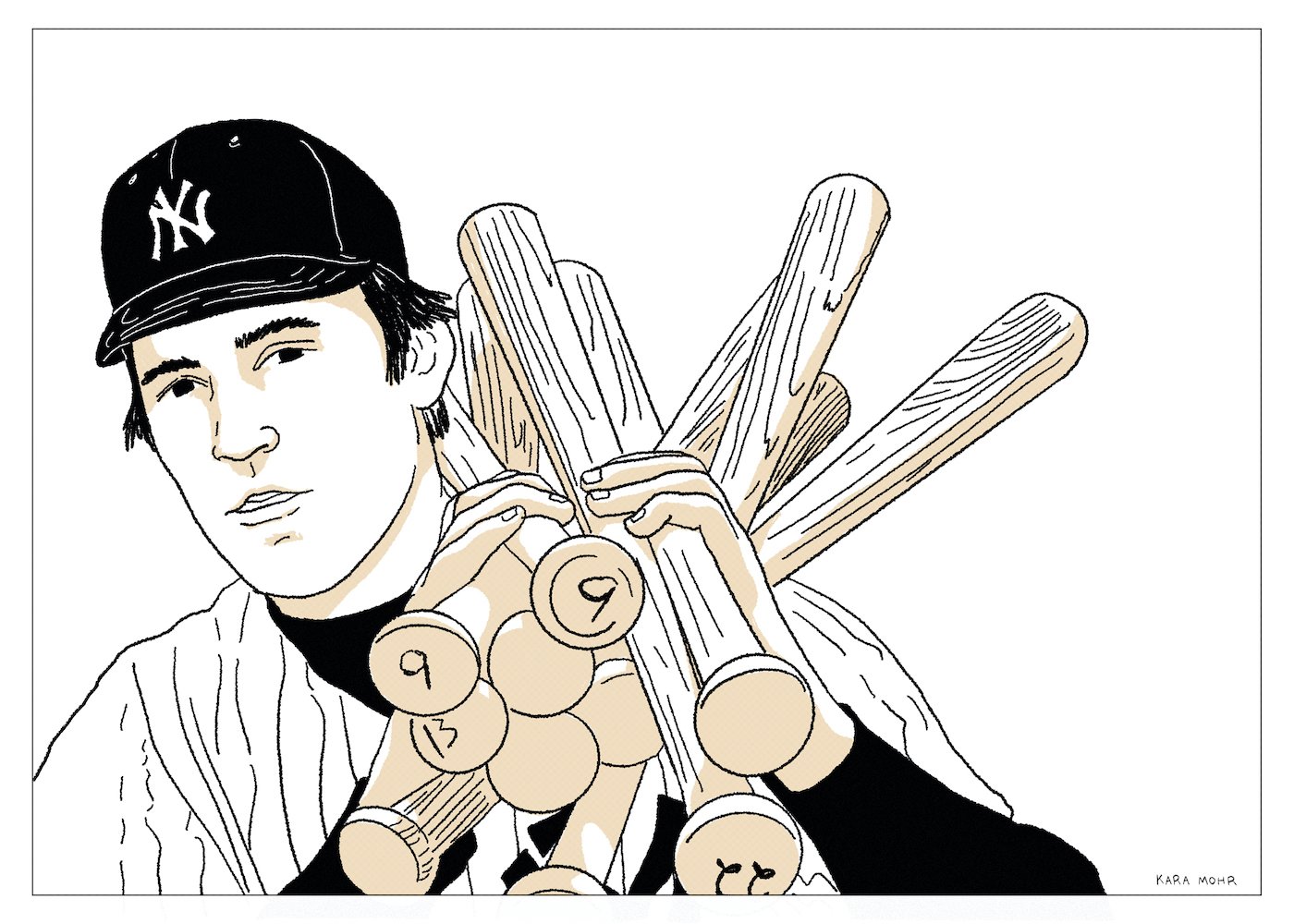

Graig Nettles “Vigilante”

First off, his name is Graig. G-R-A-I-G. It’s not Greg or Gregory. And it’s not Craig. Graig, with two G’s has more teeth than Greg or Craig. Graig looks possibly Welsh or Gaelic and like it wants to have more than one syllable. It’s a name that has caused confusion for decades, spawning baseball card typos and debates among young Yankee fans back in the day. And yet, in spite of its oddness, there’s no other name that would have worked. Of the twenty plus thousand people to have played major league baseball, only one is named Graig. Moreover, etymology suggests that “Graig” roughly means “vigilant.” And while Graig Nettles was many things on the field — an elite fielder and a perennial home run threat — and many more things off the field — a brawler, a rule bender, and a loyal teammate — he was absolutely nothing if not vigilant.

Greg Luzinski “The Bull”

Baseball has provided us with a handful of quirky, if semi-validating, proof points for the theory of “nominative determinism” — the idea that a person’s name somehow determines their livelihoods. There’s Cecil and Prince “Fielder” (neither of whom were known for their gloves). “Homer” Bailey and “Homer” Bush (the former a pitcher, the latter not exactly a slugger). Maybe Rollie “Fingers” qualifies (admittedly a stretch)? How about Grant “Balfour” (ball four)? Those rare examples are all well and good, but also confirm that ballplayers are personified less by their names than by their nicknames. “Charlie Hustle.” “Hammerin’ Hank.” “Steady Eddie.” These, much more so than first or last names, predicted the destinies of their owners. However, in the roughly one hundred and fifty years of professional baseball, no nickname has better suited its player than Greg “The Bull” Luzinski — a colossal man, put on this earth to annihilate baseballs and, one day, sling BBQ.

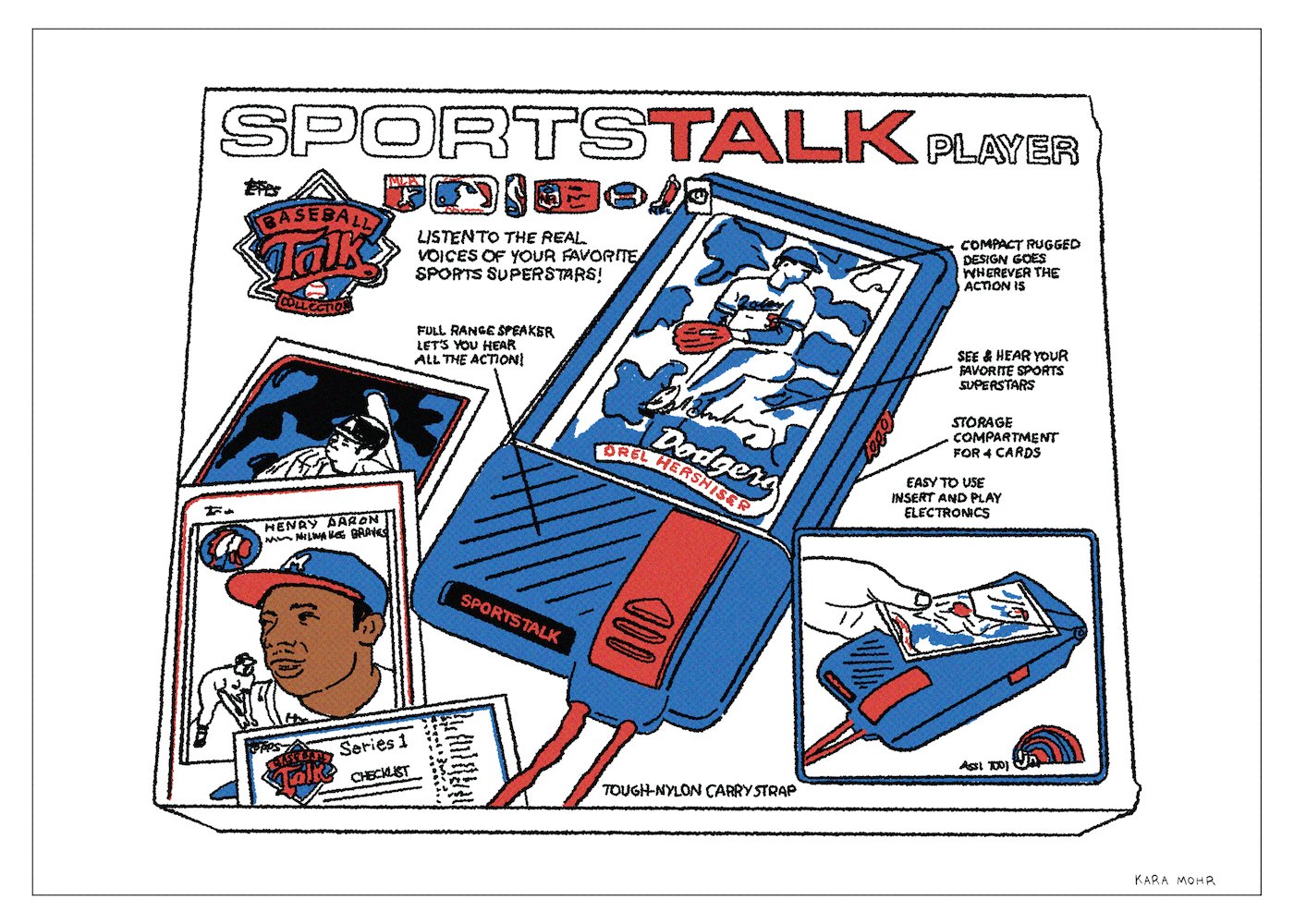

LJN Corporation “Topps Sports Talk Player”

First released in 1959, the Braun TP1 is a masterpiece. The phono-radio is considered by many to be a high water mark of twentieth century product design — its functionalism a complete validation of Dieter Rams’ “as little design as possible” ethos. Thirty years later the LJN toy company and Topps paid homage to Rams’ pièce de résistance with their Sports Talk player and Baseball Talk cards. The electronic player was actually a blue and red plastic portable phonograph and the cards resembled Topps’ bubblegum variety, except larger and with a miniature vinyl record pressed onto their backs. Like Rams’ TP1, the needle on the Sports Talk player sat beneath the records (cards). Like the TP1, the Sports Talk player was a feat of minimalist design and engineering. But unlike the TP1, the Sports Talk player was a piece of crap. Cheaply made. Easily damaged. Hard to explain and harder to understand. It lasted exactly one season and left behind a cautionary tale that fits somewhere between New Coke and “Ishtar.” For the record, though, I kind of dug New Coke. I thought “Ishtar” was pretty funny. And I freakin’ love my Sports Talk player.

Gordon Lightfoot “Shadows”

To the cynical or the uninitiated, “Shadows” can sound like a Will Ferrell spoof — like music for lovers who refer to each other as “lover.” Like music to be played while wearing cable knit sweaters, sitting by the fire and sipping Canadian Club. But for those who either know Lightfoot’s oeuvre or who are familiar with Seventies Adult Contemporary Rock music, the sound is not unfamiliar. On top of twelve string acoustic guitar, delicate windchimes and lite violins, Gord’s boozy baritone narrates a slideshow about middle-aged resignation and that trip to the Bermuda Triangle. Released the same year as The Clash’s “Combat Rock,” Duran Duran’s “Rio” and Culture Club’s “Kissing to Be Clever,” “Shadows” was miles from anything hip or New Wave. It was the sound of a guy singing to himself, because he had to, because he was tired and lost and the world had moved on. It was the end of the line for Gord’s minor Pop stardom, the beginning of his sober second half and the most interesting album he made after “Sundown.”

Warren Zevon “Sentimental Hygiene”

Following the unexpected success of “Excitable Boy” in 1978, Warren Zevon’s commercial prospects began to fade. “The Envoy,” from 1982, was predictably literate, frequently dark and occasionally brilliant. But, also, it flopped. Within a year of its release, Zevon was a black-out drunk divorcee, dropped from his record label and going nowhere fast. He licked his wounds, tried, failed, tried again, failed again and — eventually — succeeded in getting sober. It would be another five years before he released another album. In the interim, outside of his family, Jackson Browne, a bunch of L.A. session guys and a coterie of writers and critics, Zevon was more forgotten than he was missed. But then, in 1985, while Tom Cruise sashayed around the billiards table like a ninja pool hustler, Martin Scorsese dropped the needle on “Werewolves of London” and people suddenly started talking about Warren Zevon again.

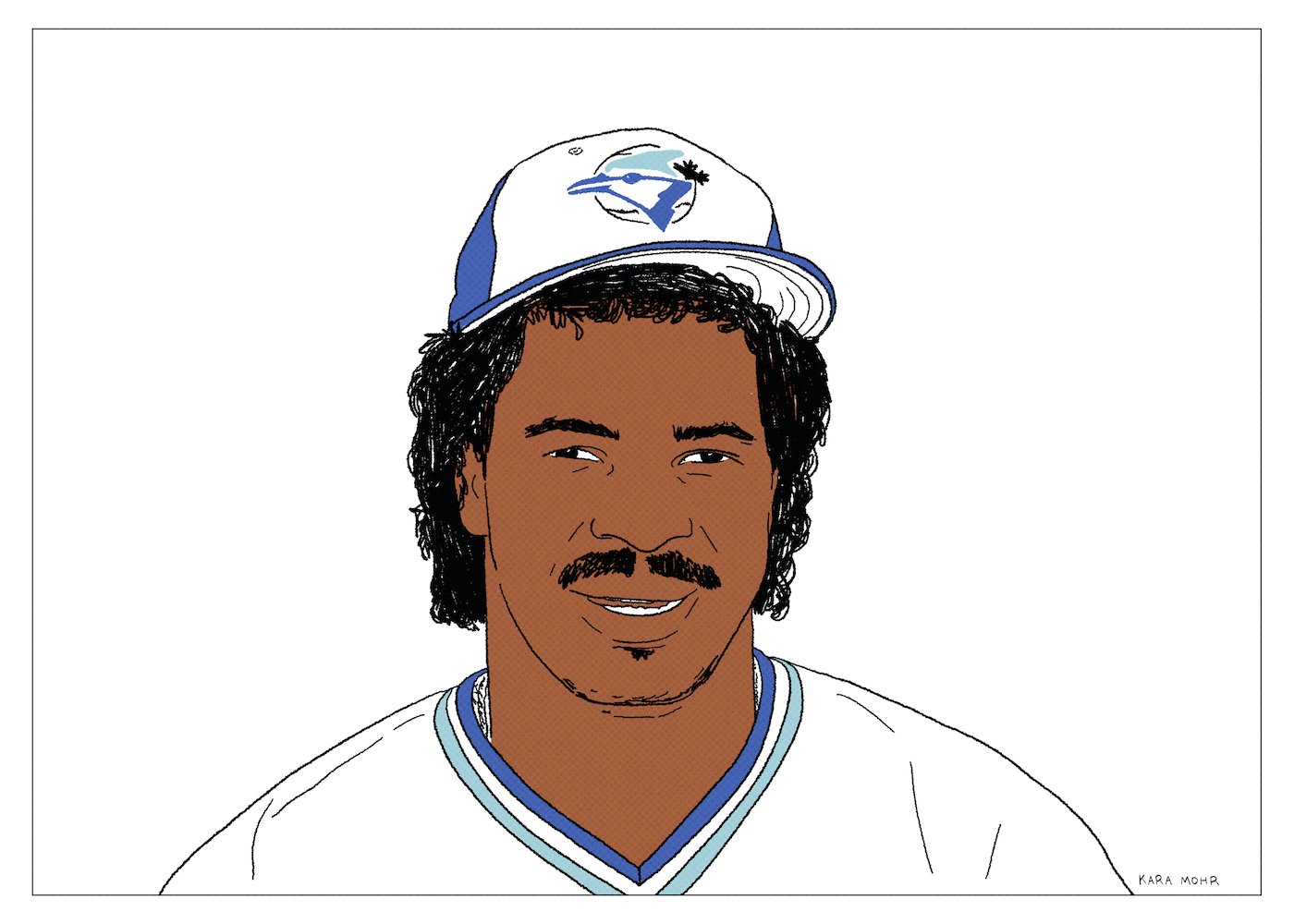

George Bell “Gone”

Having just been hit by a high, inside fastball, George Bell rushed towards journeyman pitcher, Bruce Kison, launched (and landed) a flying side kick and then immediately turned and connected with a two-handed flurry to the face of catcher Rich Gedman. Two years later, Bell won the AL MVP, edging out Alan Trammell in one of the closest races in award history. Advanced statistics, which were rarely employed at the time, have since suggested that Trammell was the far more valuable player that year. But, to my teenage eyes, George Bell was the guy. He hit towering home runs and batted over .300 and could turn into Spiderman if provoked. Back then, the Blue Jays’ slugger wore his cap on the tippy-top of his hair so as to not disturb his well-tended, lightly greased, semi-afro. That affect, with the hat perched up so high, reminded me of Apollo Creed ahead of his fight with Ivan Drago in “Rocky IV.” Like Creed, Bell’s hat “floated upon” more than it “fit on” his head. Like Creed, Bell’s external confidence betrayed some deep, inner terror. And, like Creed, George Bell completely disappeared from the sport that he’d once dominated.

Alice Cooper “Trash”

The early 80s were not kind to Alice Cooper. Sober, but restless, he tried new gimmicks. He brought more snakes onstage. He tried his hand at New Wave. He traded booze for golf. But nothing seemed to work. By the mid-80s, while Hair Metal — a genre that he’d in part given birth to — was ascending, Alice Cooper was nothing more than a charming “has been.” But then, when it seemed that he was all past and no future, he caught a massive break. Desmond Child, a longtime fan and, more importantly, the super-producer of gargantuan, shout-along hits by KISS, Bon Jovi and Aerosmith, offered to help the forty year old, Shlock Rocker reclaim his throne. In order to succeed in the mission, Child had one requirements. He demanded that Cooper sing about the one thing that all teenagers are obsessed with but which the future GEICO spokesman had somehow avoided for his entire career: Sex.