Eddie Murray “Steady Eddie”

To this day, it still bums me out. It’s been twenty five years, longer than Eddie’s playing career. I’ve got a family of my own now. I’ve had plenty of time to let things go. But not this. I can’t quit it. At least twice a year, I have dreams where he’s still playing. I see his name in box scores. He went two for four with a homer and three RBIs. I see him on TV up at the plate, no batting gloves, adjusting his belt, glaring at the pitcher. For twenty seasons, since I was just a baby really, I watched Eddie Murray do his job -- consistently, effectively, often amazingly. They called him “Steady Eddie” because he was exactly that. He wasn’t showy. He didn’t talk to the press. He wasn’t the most prodigious power hitter or the slickest fielder or fastest runner. But for the better part of a decade, he was the most complete hitter in the game. And for the ten years that followed, he may have been a tick slower, but he was still unerringly reliable. For two decades, I could bank on Eddie.

After a stellar first ten years in Baltimore, Eddie Murray became something of a journeyman in the sunset of his career. He was a prestige bat for hire -- a venerable presence in the locker room and out on the field. The Orioles traded him to the Dodgers in 1989. He then signed with the Mets in 1992 and the Indians in ‘94. There were sub-par, “adjustment” seasons wherein writers predicted it might be the beginning of the end. But then Eddie would lean on his wisdom and find a new gear — like in 1990, when he hit .330 for the Dodgers or in 1995, at the age of 39, when he hit .323 for the pennant winning Indians. Even in 1996, when the Indians traded him back to the Orioles, Eddie managed twenty two home runs and hit .333 in the postseason. I mean, I knew it couldn’t go on forever, but I sure hoped it would.

But then, 1997 happened. In the offseason, he’d signed with the Anaheim Angels, a middling team, not far from his home, that could benefit from the learned designated hitter. Eddie was forty one when the season started and looked to be in surprisingly good shape. The story was that he was there for his bat, but also would contribute like a player coach in the clubhouse. From the very start of the season, however, it was clear that something was not right. Eddie was always a slow starter, he normally sizzled in the summer and then found a new gear in September. But, in 1997, he started lukewarm and just increasingly cooled off, day after day. The power surge never came. The batting average remained mired around .200. He was put on the disabled list, but, when he returned, not much changed. For two decades, he’d produced 120-160 OPS and positive WAR. But, in middle age, he was clearly a liability. Mid-season, the Angels finally did the decent thing — they released him. I presumed that it was the ignominious conclusion to an otherwise glorious journey.

Within a few days, however, against all odds, and probably good sense, the Los Angeles Dodgers signed Eddie to a contract. The Dodgers were Eddie’s true hometown team. He’d played there before and maintained a good relationship with their General Manager, Fred Claire. The Dodgers were not great at the time, but they were in a divisional race. Reports were that Eddie was being brought in as a high end, pinch hitter. Worse still, the club wouldn’t be able to formally bring him on to the team for a few weeks, when roster sizes expanded. Until then, Eddie would keep warm in the minor leagues. Yes -- the minors. Eddie Murray, the third player in baseball history to achieve five hundred home runs and three thousand hits, would be playing for the Albuquerque Dukes in the Pacific Coast League. He’d last played at that level in 1976. In between, he’d quietly, but magnificently, marched his way towards the Hall of Fame. But now, in middle age, for reasons I couldn’t fully understand, he was going to play ball with the kids, until the grown ups invited him back up to the Big Show. It sure sounded like the ultimate indignity. I couldn’t understand why he didn’t just tip his hat and walk away. I couldn’t stomach it. I felt like I was personally being demoted. It was humiliating. But, clearly Eddie Murray is a bigger man than me. He took his assignment, reported to New Mexico, and showed up for work.

Over the next two weeks, I scoured the Albuquerque newspapers for reports on the Dukes. Information was scarce in those early internet days, but it seemed like Eddie was thriving. The team understandably loved having a legend around. And Eddie was mashing. He was batting almost .400 and hit a bunch of home runs. Surely, I concluded, he still has plenty in the tank. Triple A players who succeed generally thrive in the majors. He hadn’t lost his faculties. Maybe he just needed to rehabilitate. Maybe he’d, once again, found a new trick. Maybe he’d be back and would help lead the Dodgers to the pennant. Maybe he’d play on until he was forty three. Maybe he’d play forever.

Eddie was called up in September and, true to their word, the Dodgers used him as a pinch hitter. It was a role that the perennial All Star was not used to. He was dutiful in his efforts. He had a couple of hits -- even one game winner. But, there were no more home runs. No more doubles. Seven final at bats. A quiet, but very professional, whimper. And that was it. The Dodgers didn’t make the postseason. As most expected, but I feared, Eddie Murray retired soon thereafter.

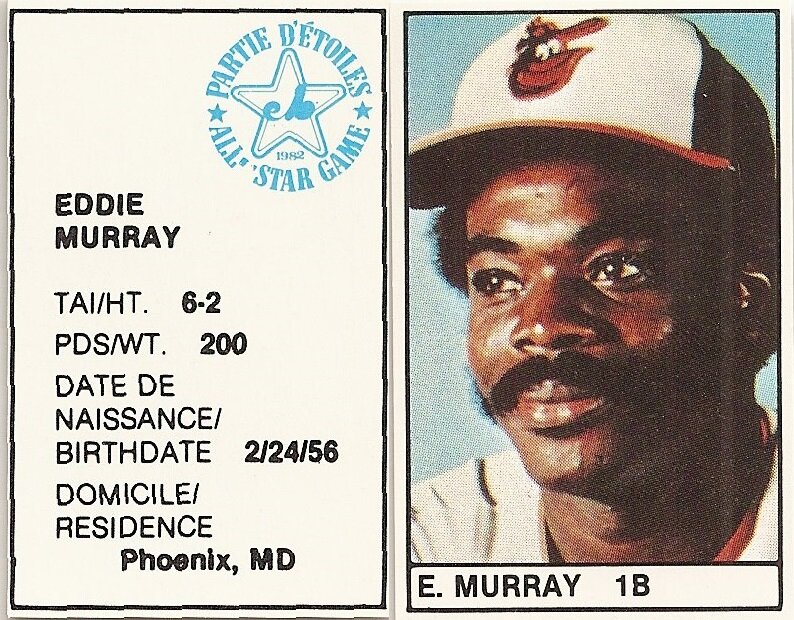

1998 kind of sucked. A baseball season without Eddie was no season at all. I was a couple years out of college, in a shitty administrative job, working on a start-up on nights and weekends, but secretly terrified of making the leap. For most of my life, Steady Eddie had been my metronome. A lot of kids have sports heroes, but I was unusually attached to mine. I had books filled with his baseball cards. When I was president of my middle school student council, I contrived to organize a class trip to a Yankees Orioles game, so I could see Eddie play. As a teenager, when my friends wanted to razz me, they’d shout, “Murray sucks.” It was an oddly effective means of provocation. As a child, Eddie had imprinted on me. His wide and patient batting stance. His iconic mutton chops and mustache (without a beard). His humble trot around the bases. His famous, steely boycott of the media. His workmanlike consistency. His inordinate talent. For all of those reasons, and many others that are so deeply ingrained as to be ineffable, Eddie Murray was my guy. No matter that I was a scrawny, white, Jewish kid. I wanted to grow up and be like him.

During my two decades of worship, there were certainly times when my faith buckled. Some writers disdained Eddie’s silence. My fellow New Yorkers hated his Yankee-killing talent. In 1989, the Orioles front office questioned his effort on the field and then traded him, like he was a commodity. His first season as a Dodger was a struggle. Same thing with the Mets. And the Indians. In 1990, he led the Major Leagues in batting but lost the NL batting crown because Willie McGee, who got traded towards the end of the year, had a slightly higher average while playing in the NL (his average dipped below Eddie’s by year’s end but batting champions are determined based on their performance in each league). What should have felt like a second half triumph, felt like a grave injustice. And then, in 1996, just a year after he helped lead them to the World Series, the Indians traded him back to Baltimore in what reeked of ageism to me. All of these moments stung. But they eventually healed. Eddie seemed to have forgiven them all and so I followed suit. But the bruises from that final season in 1997 -- they never really went away.

Why couldn’t I accept something that was inevitable? Professional athletes don’t play forever. Eddie had a wondrous career. It was just time. He knew what his body and his heart were telling him. Logically, I understand. But, the trauma of 1997 persisted for me. Some part of this was my own fear of aging -- the notion that you irretrievably lose something around the age of forty. The idea that it’s unavoidable -- that at some point you have to stop with the games and get on with whatever is left to do with your life. Equally, if not more so, it was the inversion of a foundational model. Eddie Murray was “Steady Eddie.” He was as reliable as any ballplayer has ever been. This wasn’t just my feelings about him. This was statistically true. So, for the steadiest of men to suddenly become unstable -- to miss easy fastballs and to lose ten to twenty feet of distance on their long balls -- that seemed wrong. And a little traumatic. It felt like its own death.

For more than twenty years now, I’ve been mourning Eddie’s final season. Since 1997, he had a couple stints as a batting coach. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame on his first ballot. He’s had his own vintage of red wine. He’s had a popular IPA named after him. He occasionally shows up on TV, smiling and more talkative than he ever was in his playing days. And yet, something about that last gasp in the Majors (and the Minors) never settled for me.

But then, just last year, I found a way back. I was on Cameo, looking to see if Kyler Murray -- my son’s football hero -- was possibly offering video messages for sale. It seemed unlikely. Kyler Murray is a superstar and wealthy in a way that the athletes of my childhood never were. And I was right -- no Kyler. But, in my keyword search, someone else popped up: Eddie Murray, the man of few words, was on Cameo. It seemed impossible. I was sure it was a mistake or a prank. But there was no world in which I wasn’t going to try it out. I made a special request. I asked Eddie to talk about his friendship with Cal Ripken Jr. and to dedicate his short video to me and my dearest friends. I put in my credit card number and assumed nothing, but hoped for everything. Then, I waited.

Cameo suggests that it could take up to five days to get a response, but, in my experience, it normally takes less than two. So, after one day without a video back from Eddie, I was unmoved. After two days, I was unsurprised but not disappointed. After day three, I was resolved to move on. On the evening of night four, however, my phone got a text alert and my email indicated that I had a new message. To my complete amazement, both confirmed that my Cameo from Eddie was ready. I clicked and, with butterflies fluttering around in my stomach, watched as Eddie appeared in what seemed to be his home office. For the next two minutes, he said my name, my friends’ names, and shared stories about playing ball with his buddy Cal; about showing up to the field, playing nine innings, exhausting themselves, and then regrouping a couple hours later to play video games together and blow off some steam. I almost couldn’t comprehend the story. For one, it was my hero talking to me. But, moreover, there was a childlike joy in his retelling. It was not a reticent, possibly embittered, sixty-something year old ex-athlete. And it wasn’t even a twenty-something All Star. It was more like a kid, playing ball and having fun.

That two minute video was all I needed to reframe my narrative. I shed the veil. I changed from my dark, funereal suit into a sunnier, linen number that breathed. I never dreamed about 1997 again. I had peace of mind and Eddie had given it to me. Those pitiful days with the Angels seemed irrelevant. When I rewrote the movie, I traveled back to New Mexico, where Eddie was more semi-pro than professional. He was playing with men half his age — some of them kids, really. He was hitting every pitch in every direction. A handful flew over the fences. And he was smiling. Because he loved playing baseball. And because baseball is a game that some (few) get to play as a career. But it’s still a game. And, I am certain that Eddie Murray knew that in 1997. So, in between his stint with the Angels and his final march home to the Dodgers, he just played ball in the hot sun for a couple of weeks.