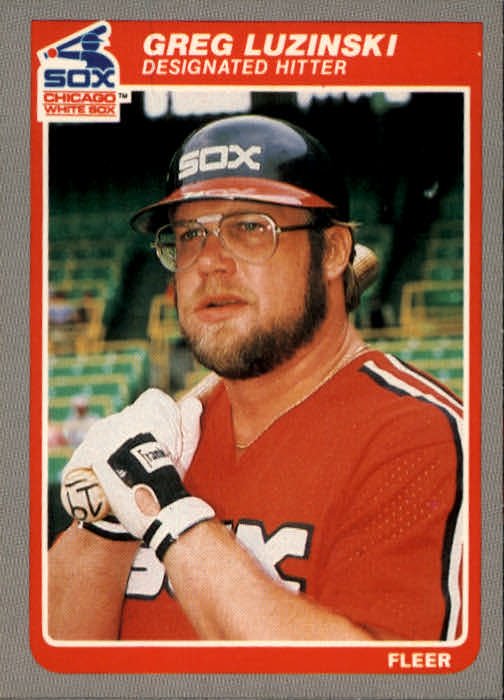

Greg Luzinski “The Bull”

“Nominative determinism” is the idea that people’s lives — and specifically their livelihoods — are determined by their names. It’s a hypothesis that, today, elicits giggles and eyebrow raises. But centuries ago, “Fishers” were fishermen, “Smiths” were metalworkers and “Steins” were stonecutters. If you worked in a mill, you might have been named “Miller” and, in turn, your children and their children would inherit that name and, in many cases, that occupation. You get the drift — in fourteenth century Europe, “nominative determinism” was more a matter of fact than it was hypothetical.

Fast forward half a millennium and the idea sounds far flung. My last name is “Wishnow” but I’ve never considered a career as a genie. And when I traced the origin of “Wishnow” back to its Eastern European roots and discovered that it meant (roughly) “cherry tree,” I did not consider cultivating orchards or baking pies or anything like that. That would be farcical — right? Of course it would be. Which is why in those rare instances when “nominative determinism” crop ups in contemporary culture, it is for one reason: laughs.

The best, modern instance of “nominative determinism” occurs during the fifth episode of season three of “Seinfeld,” when Jerry is hounded for a decades-old library fine by “Detective Bookman.” Jerry tries his darndest to keep a straight face while Bookman, played to deadpan perfection by Philip Baker Hall, gumshoes the case. In Hall’s commitment to the performance, we almost forget how silly the gag is. We watch Jerry breaking character, fighting back laughter, while we quickly skip over the name “Bookman” and the idea that, while there are certainly firemen named “McBurney” and lawyers named “Justice,” “nominative determinism” is obviously more quaint than scientific.

In fairness to the theory, major league baseball has provided us with a handful of quirky, if semi-validating, proof points over the years. There’s Cecil and Prince “Fielder” (neither of whom were known for their gloves). “Homer” Bailey and “Homer” Bush (the former a pitcher, the latter not exactly a slugger). Maybe Rollie “Fingers” qualifies (admittedly a stretch)? How about Grant “Balfour” (get it, ball four)? Those rare examples are all well and good, but also confirmation that baseball players are personified less by their names than by their nicknames.

“Charlie Hustle.” “Hammerin’ Hank.” “Steady Eddie.” These, much more so than first or last names, predicted the destinies of their owners. However, in the roughly one hundred and fifty years of professional baseball, no nickname has better suited its player than Greg “The Bull” Luzinski.

Born and raised near Chicago to hearty Polish parents, Luzinski was six feet, one inch tall, and weighed two hundred and twenty pounds as a nineteen year old rookie, but played porfessionally closer to three bills. And though his weight was the subject of whispers, jokes and (yes) pride throughout his career, his greatest gift was his hands. The Bull’s rare combination of tremendous girth and surgical hand-eye coordination placed him among a very small group of chesty sluggers that included The Bambino, Harmon Killebrew and fellow Pole, Ted Kluszewski.

While he frequently swung and missed, Luzinski was not an all or nothing hitter. When Dave Kingman, for example, hit a home run, you marveled at the distance but also assumed that it was kind of lucky that he actually connected. When Luzinski struck out, you assumed simply that he’d simply been beaten by a good pitcher. But also you felt fortunate for the baseball — that the ball had gotten lucky. Conversely, when hit a ball five hundred feet — as he did several times during his career — you understood that to be the logical outcome. Luzinski’s thighs, hands and biceps were designed to annihilate baseballs.

During an era when forty home run seasons were rare (and when Mike Schmidt owned most of them), and when sluggers who also hit for average were even rarer, The Bull was a reliable three hundred, thirty home run guy. While in Philly, he was twice the runner up for NL MVP, a four time All-Star and a perennial fan favorite. On May 16, 1972, Luzinski hit a replica of the Liberty Bell that was perched at the very top of the fourth tier of center field at old Veterans Stadium — a feat that had not been accomplished before and would never be duplicated. For all of the local fans’ ambivalence for their greatest players — Schmitty and Lefty — Phillies’ fans were all in on The Bull.

After a string of NLCS appearances between 1976 and 1978, The Bull, Schmitty, Charlie Hustle, Lefty and Tug finally brought home the hardware in 1980. Following a strange, occasionally wobbly season wherein manager Dallas Green platooned established veterans and wherein the younger, ascendant Astros seemed the like a better bet, the crafty old Phils defeated George Brett and the Royals in the World Series four games to two.

Luzinski’s first (and only) ring came in his tenth season in Philly but also, his poorest one. Struggling with injuries and a rash of prolonged slumps (which he blamed on the platooning and which the media blamed on his weight) The Bull hit just .228 with nineteen home runs. He was twenty-nine at the end of the season, but it was an old twenty-nine. A heavy twenty-nine. The Bull had been slugging professionally since he was seventeen. Thousands of plate appearances. Thousands of titanic swings. And so, when it became clear during the offseason that he and The Phillies would be parting ways, it made sense. It seemed entirely possible that he’d fulfilled his destiny. In 1971, he’d arrived on a team that placed last in the NL East. Ten years later, he helped catapult them up to a World Series title. He’d accomplished so much during his time in Philly. And now he had his ring. And, that very well could have been his destiny.

But, obviously, it was not. That offseason, Luzinski signed a three year contract with his hometown Chicago White Sox, who were good on the verge of great. Alongside Pudge Fisk, Harold Baines, Lamar Hoyt and under the steady hand of manager Tony LaRussa, The White Sox appeared poised for a title run. That Luzinski would come home, hit bombs onto the roof of Commiskey and ultimately carry the Sox to the promised land seemed almost scripted. That he could play designated hitter and entirely avoid the outfield, where he was a marked liability, made too much sense. That Chicago fans would accept — even applaud — his girth and age, was unquestioned.

And for roughly three years, it mostly played out that way. Luzinski returned (close) to form, leading the Sox to a string of winning seasons including an ALCS appearance in 1983. In both ‘81 and ‘83, The Bull was named Designated Hitter of the Year. Next to Carlton Fisk, he didn’t look like such a widebody. And next to Ron Kittle, his geeky glasses didn’t stand out so much, either. Thirteen seasons into an already storied career, Luzinski was nearing three hundred home runs, at a time when that milestone really meant something. Four hundred seemed a likely outcome. So did another division championship. He was slowing down, but he also looked as comfortable as he’d ever been. The DH rule was practically designed for Bull. That he could play that role and play it in Chicago felt preordained. It felt right. It felt like it was meant to last.

And maybe it was. But, also, playing designated hitter for his hometown club was — amazingly — not Greg Luzinski’s destiny. In 1984, as he battled through injuries and watched his club fall far below .500, The Bull hit a wall that he could not barrel through. Though he was still just thirty-three at the season’s end — a full decade younger than Pete Rose, twelve years younger than Phil Niekro and six years younger than Steve Carlton — he was done. He got an offer to pinch-hit. He was floated the idea of returning for a pennant run. But, he was ready to move on. The lack of interest in signing The Bull — who’d repeatedly proven capable of turning things around after an off year, who was one year removed from being named the league’s best DH — was surprising. But less so than the resolve with which Luzinski walked away and did not look back.

After saying farewell to his playing days, Luzinski moved back to New Jersey, where, for seven years, he coached high school baseball and football. Those days on the road, the time away from family, the spotlights, the mashes and the whiffs — they were behind him. He’d earned the best sort of celebrity, closer to Norm from “Cheers” than to Babe Ruth. He could have his privacy but could also still walk into a Miller Lite commercial, gut gently cascading over the waist of his khakis, pick up a golf club and drive a ball many (many) miles away, onto a green near an unsuspecting foursome…in China. From the outside looking in, it sure seemed like a very good life — collecting an MLB pension, operating a (successful) health and racquet club in Jersey and, eventually, quietly returning to The Bigs as a hitting coach.

But, as fitting and deserved as it all sounded, (you guessed it) Greg Luzinski was not destined to be an MLB batting coach or a Miller Lite spokesman or a high school coach. And he certainly was not destined to be the face of a tennis and racquetball club. But none of this was clear in the Eighties or Nineties — it was not until 2004 that his full, proper, no brainer, manifest destiny would be revealed.

In the Spring of that year, the Phillies moved into Citizens Bank Park where, in section 104 of the brand spanking new stadium, stood Greg “The Bull” Luzinski, slinging pulled pork, sausage and ribs at “Bull’s BBQ.” Though the idea was swiped from Boog Powell’s “Boog’s BBQ” at Camden Yards in Baltimore, Bull’s BBQ was an invention so good and so obvious that it's frankly a wonder that it took twenty years for Luzinski and The Phillies to figure it out. Though not from Texas or The Carolinas of Missouri, where BBQ reigns supreme, Luzinski was a lifelong grill-master. He loved slow cooking. He loved rubs and sauces. And he loved the people of Philadelphia.

Bull’s BBQ is not a vanity project. It’s not a gimmick. Or, at least, if it started out as either, it quickly became so much more. From the outset, Luzinski would frequently work the stand, signing autographs and regaling alongside nostalgic fans. He took the product, and especially the flavors, very seriously. At one point, the Chicago White Sox opened their own Bull’s BBQ, marking the first time (to my knowledge) a ballplayer was the name and face of concession stands at multiple stadiums and in both leagues. To this day, Bull’s BBQ not only survives at Citizens Bank Park — it thrives. It’s widely considered to be the best food at Phillies’ home games and among the best BBQ in any MLB stadium.

Now seventy-two years old, Greg Luzinski’s destiny is truly, finally apparent. Great an athlete as he was — he was not born to be Babe Ruth or Harmon Killebrew or, even, Ted Kluszewski. He wasn’t put on earth to pitch beer or to mentor Jose Canseco and Mark McGwire. He was called “The Bull” for many reasons, but ultimately because he was destined to make mouth watering sausage, ribs and pulled pork. He was meant to do that eighty one days per year at Citizens Bank Park and, probably, another hundred or so at home with his family and friends. And maybe — just maybe — when he wasn’t making BBQ, he was meant to show up at some senior rec softball game and hit a slow pitch five hundred feet.