Hot Snakes “Jericho Sirens”

In 2001, I made a lot of bad decisions. The worst of them, however, was probably the 1966 baby blue Vespa that I bought online, site unseen. Like many naive, twenty-something Americans before me, I’d fallen in love with the scooter during a post-college trip to Italy. But, unlike most twenty-something Americans, upon return, I promptly emptied all eight hundred dollars from my checking account to have one shipped from Southern California. And unlike the dozen or so twenty-something Americans who, like me, actually bought a vintage Italian scooter, I knew precisely zero about engines. I had never operated a clutch. I’d only once fixed a flat tire. And I wasn’t especially keen on learning a new trade.

Honestly, I can’t really explain the decision other than to say that I loved the way those old Vespas looked and that I pictured myself bopping around Brooklyn, visiting friends, and being that guy with the old, blue scooter. And that’s precisely what I did, for all of six months, until the first signs of mechanical failure appeared. Before I sold it for parts, however, I put it to good use. I rode to shows in Williamsburg. And I made regular visits over to Park Slope, where the woman I was dating lived. I remember the route clearly -- over the Gowanus Canal, right on Third Avenue, head south towards Nineteenth Street and then turn left and head east towards the modest brownstone where she lived cheaply with her roommate. I probably made the trip to that shitty apartment twice a week, grinding the gears and hauling a heavy, old bike lock along the way. In retrospect, the whole thing was kind of stupid and unnecessary. But it made me feel sophisticated and spontaneous -- two things I am definitely not. But, it did provide one great benefit. It delivered me to the doorstep of Cranky Rick.

“Cranky Rick” was the nickname that my girlfriend and her roommate gave to their neighbor. He lived in the apartment across the hall, which I assumed cost the same or less than my girlfriend’s — which was not very much money. By the way she described him, he sounded like a middle-aged advertising hack. I didn’t know his real name. And I presumed that “Cranky Rick” was not his preference. Details were scant, but he was alternately described as a stoner, a dork, talented and irritable (hence, the nickname). By the way they joked, I sensed a meaningful age gap. If I was forced to guess, I would have said that Cranky Rick was closer to fifty than thirty.

Over time, however, more details emerged. Cranky Rick played in a band. Cranky Rick was possibly a web designer. Cranky Rick was really smart. Cranky Rick was kind of cool. These were all rumors, mind you. Months into my visits, I’d never seen or met the guy. Then, came that inevitable evening when, fresh off my Vespa, I walked into that apartment and saw someone who I assumed was Cranky Rick, inside, hanging out. I approached. He turned around. And I’m not sure if I’ve ever been more confused than I was at that moment. Because Cranky Rick was definitely not fifty. He looked to be in his early thirties. And he looked not unlike -- in fact, almost exactly like -- Rick Froberg from Drive Like Jehu.

So, yes. Obviously. Cranky Rick was Rick Froberg, the lead singer and guitarist from the band that had figured out the Math that turned Hardcore into Post-hardcore. And the guy who was, at the time, the frontman for Hot Snakes, the greatest club band I have ever seen. I had learned of Jehu through mixtapes and legend, but I’d never seen them live. Plus, I’d gotten hip to the power of “Yank Crime” about five years too late. But Hot Snakes were the present. They were vital and ferocious. They were making music right now. I’d seen them, heard them and been flattened by them.

To this day, the three best bands I ever saw live in small venues around New York City were (in order) Hot Snakes, The Constantines, and Rye Coalition. Rye, who existed almost entirely because of Minor Threat, AC/DC and, yes, Drive Like Jehu, were the most fun of that trio. They made you want to get into trouble. The Constantines, who also would not exist without Reis and Froberg, were the most inspirational. They made you want to start a riot or a movement or something. But The Hot Snakes were a different species. They were nuclear. They were atomic. Older. More knowing. More who-gives-a-fuck. But also, more, we-give-the-most-fucks. They were goddam heroes.

To me, Hot Snakes were a miracle. They were a miracle for surviving the major label debacles of Drive Like Jehu and (though less of a debacle) Rocket From the Crypt. They were a miracle for how John Reis constructed riffs, seemingly from a twenty-sided die that he would roll, play, and then roll again. They were a miracle for how Rick could scream precisely on the melody in between the two guitars and then get low and menacing, closer to the bass. Of course, they were a miracle for how much tension they could create and how quickly they could release it. But, mostly, they were a miracle for how they balanced Rick’s cynical, fuck-it-all-ness, with John’s earnest, fuck-yeah-ness. John made Rick a little more Rock and Roll and Rick made John a little more Hardcore. That was their greatest miracle.

No matter how miraculous or legendary or heroic Hot Snakes appeared to me, though, it seemed pretty clear that, for Cranky Rick in Park Slope, Brooklyn in 2001, their work was hard work. You could see it in his eyes. You could see it on stage in the sweat. You could feel it in the speed. But you could also imagine it based on the three thousand miles that stood between the band’s founding members. Recording was hard. Practicing was hard. Touring was hard. And living was hard. John Reis and Rick Froberg were giants to me and thousands of others, but they were patently not stars. They had to live the life of cult heroes -- adoration that outsized their fortune; talent that exceeded their opportunity. They were members of a club that included people like Moe Tucker from the Velvet Underground, who worked at a Walmart in the 1980s. Or Bill Million of The Feelies, who spent most of the 1990s and 2000s as some sort of speciality locksmith at Disney World. Or David Kilgour of The Clean, who sold paintings on the side, in between Clean reunions and modest solo records and tours. Frankly, it’s a massive club. And all of of its members have that one thing in common -- their fortunes always lag far behind the adulation of their cults. It’s enough to make one cranky.

In 2002, I heard two generationally great songs about thirty something year old dudes looking over their shoulder. James Murphy wrote the one with better beats and the funnier jokes. Rick Froberg wrote the other one -- the one that almost can’t bother with pace and which sounds dead serious. LCD Soundsystem’s single was, of course, called, “Losing My Edge.” The opening track on Hot Snake’s “Suicide Invoice” was called “I Hate the Kids.”

Nobody does anything

Wrong

Nobody is a dilettante

Everybody does everything

Everything they want

Fine clothes

Find work

Grab a spade

Get in the dirt

The older you get

The less you're worth

I wanna watch you hit the market full force

I hate the kids

While John Reis and Rick Froberg eventually ended up back together, their roads diverged considerably after Drive Like Jehu broke up. Reis was the charmer, the believer, the extrovert. He was the guy who took his riffs, added costumes and nicknames and made an honest go at sub-popular stardom. He was the first one to tour the world. He was the one who started his own label. The one who offered free tickets to fans with RFTC tattoos. The one who stayed in San Diego and became the swami godfather of a scene that would produce Three Mile Pilot, Black Heart Procession, Pinback, The Locust, Heroin, No Knife, Tristeza and countless other kind of weird, kind of Hardcore, kind of artsy bands than I barely heard or saw.

Rick, meanwhile, bolted for New York. He was not a carnival barker like John was. He was more like a reluctant fire eater. And though he’d probably resist the label, he was an artist -- a designer. He seemed more introverted than John. And, yes, more cynical. It was obvious that he loved playing music. But music also increasingly looked and sounded like “work work” for him. And, though it might not always be the case in your twenties, by the time you get to your thirties, work has to pay. So, while Rick always seemed to give a shit about his bands, he seemed to give much less of a shit about the scene.

The amazing thing about Rick and John’s roads is not that they reconnected. That seemed almost inevitable. No -- the amazing thing is how they meandered and who they intersected with. If one were to do a band by band, genre by genre consideration of Indie music after 1996, it would be reasonable to conclude that Drive Like Jehu was among the most influential Post-Punk bands. Some combination of them, Minor Threat, Slint and The Pixies, functionally invented Post-hardcore and presaged Math Rock, Emo and Screamo. All together, that’s a genome that stretches from Headhunter and Gravity out West to Touch and Go and Southern in the Midwest to Jade Tree and Dischord in the East. It’s a massive footprint. From the weirdness of The Blood Brothers to the greatness of Nirvana, it’s hard to not hear the influence of John Reis and Rick Froberg.

And for all that, Rick Froberg landed in a tiny apartment in the “wrong part” of Park Slope, teaching himself Adobe Flash in part, presumably out of genuine curiosity, but also, in part, out of financial necessity. Onstage, he looked completely locked in — deadpan, but also inspired. But offstage, well, he seemed rightfully cranky. So, after three monumental albums and at least one world tour, Hot Snakes called it a day in 2006. Brooklyn was expensive. Bush was still president. Nobody was buying albums. And Swami John still lived in San Diego. The break-up was nothing if not practical.

Over the next ten years, John revived RFTC long enough to cut a live album and to a say farewell. He then formed The Night Marchers with Gar and Jason from Hot Snakes and spent his off days manning the shop at Swami HQ and doing voice work for “Yo Gabba Gabba.” Rick, meanwhile, stayed in New York and formed Obits, who put out three albums on Sub Pop. A decade after Hot Snakes last played, John was still a full time music man but Rick was more of a “paid amateur” (to use his words). When he played he still sounded like Cranky Rick -- melodically screaming or howling from an unhappy gut. But compared to Hot Snakes, Obits was a lower stakes affair. They weren’t racing to get somewhere. There was less tension. Less precision. But, also, there was more Rock and Roll. John Reis was on the other side of the country, but he’d left a trail.

In 2010 and, again, in 2012, there were “Hot Snakes reunions.” And, by all accounts, the performances were great. But these were mostly one-off “money gigs” or short runs. They were undoubtedly a joy for fans, fun for the band but also, probably, really inconvenient. A decade after “Audit in Progress,” John and Rick were firmly middle-aged and Hot Snakes was firmly an occasional, if the money is right or the stars align, kind of project. It was a beloved inconvenience, more dormant than alive. Or, so I thought.

As a result, in late 2017, when it was announced that John and Rick were getting the band back together for a national tour, I was a little surprised. That sounded like a commitment. And when it was later revealed that the band was also releasing a new album, in 2018, on Sub Pop, I was honestly kind of floored. Not floored like “The Smiths are reuniting??!!” And, not surprised that this was the band that John and Rick were resurrecting. John could have made more money with RFTC. They both could have made more money as Drive Like Jehu. But these guys were nothing if not principled. Those two, more legendary bands, were dead. Hot Snakes still had a big, beating heart. So, my surprise was less a product of their reformation and more that they were going back into the studio, risking the legacy of their almost-perfect trilogy. And that the album was coming out on Sub Pop and not Swami. As a wide-eyed fan, I was giddy. As a middle-aged cynic, I was slightly concerned. I wondered both “why would they?” and also “could they still?”

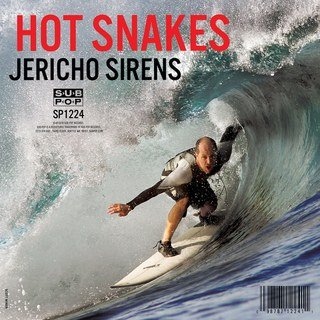

The answer to that former question was “none of my business” and to the latter was “shut the fuck up.” Released in 2018, “Jericho Sirens” is different from its predecessors in three, not minor ways: (1) It was released by a different, larger and more established indie label. (2) Both Jason Kourkounis and Mario Rubalcaba play drums. And (3) its cover features a fairly spectacular photo of bassist Gar Wood surfing inside a curl rather than a two color illustration by Rick Froberg. But those differences seem incidental, to the point of being irrelevant, once you press play on the album. Because, from its very start, “Jericho Sirens,” like the first three Hot Snakes records, is shot from a canon or a nuclear aircraft carrier or something. I always thought that half of “Automatic Midnight” -- from "If Credit's What Matters I'll Take Credit" until “Our Work Fills the Pews” -- was as breathless and sharp as Hardcore could get. But, honestly, the first six tracks on “Jericho Sirens” -- from “I Need a Doctor” through “Death Camp Fantasy” — almost match that pace.

At ten songs and barely thirty minutes, “Jericho Sirens” is the shortest Hot Snakes album. It’s mostly a breakneck speed -- lots of tension and not a lot of room to breathe. It’s still the same, strict palette. Rick either screams in harmony with the twin guitars or hangs out near the bass, in that lower, Iggy register. John’s riffs, as always, are tightly coiled, rearranged and recoiled. And Gar’s bass is heavy and aggressive but never plodding. Frankly, it’s astounding just how much the new stuff resembles the band’s first two records and just how little time has softened them. If anything, in 2018, Hot Snakes sound more desperate and more racing than their younger selves.

It’s possible that every song on Hot Snakes’ fourth album is actually about death. But, by my count, there are at least five that are explicitly concerned with the subject. The first of that handful, “I Need a Doctor,” starts the album. As opening salvos go, this one is a doozy. The guitar play is fast, but road tested. The more Rick sprints, the more inventive John gets with his riffs. It might also be the most desperate song ever sung. Not lovelorn. Not lonely. Not sad. Quite literally the sound of a man who is spitting up blood near a toilet and who needs to be put on a gurney. It’s terrifying. And yet there’s a tunefulness to Rick’s screams that makes it a fun three minutes. It’s a trick that only Hot Snakes can pull off.

And then they’re off. After “I Need a Doctor,” the band reminds us how they partially invented Math Rock (“Candid Cameras”) and how they can be as Hardcore (“Why Don’t It Sink In”) as Black Flag. But after four minutes of noise and angles, they re-bait their hooks and give us “Six Wave Hold-Down,” an undeniable screamalong chasing the fine line between surfing and drowning. Its beat is steadier. It’s melody straighter. It reminds me a bit of Wire, the only other band I know that can make fast, loud noise and then, seemingly out of nowhere, pull out a perfect almost-Pop song. Just like that!

Hot Snakes can still churn like old, heavy machinery, as they do on the title track and “Having Another.” And they can still dial up searing, white heat, as they do on both “Death Camp Fantasy” and “Death Doula.” The latter presses the rhythm into painful tension only to open up for the chorus’ derisive chuckle. Plus, for a band that has a deep reserve of bilious titles (“Suicide Invoice,” “I Hate the Kids,” “Hatchet Job”), “Death Doula” has to rank near the top. Like the best Froberg lyrics, it’s alternately irate and kind of funny.

Amazingly, it’s possible that the band saved the best for last. Rick sings the absolute shit out of “Psychoactive” and then Gar really pumps the bass on the album’s closer, “Death of a Sportsman.” As the bottom starts to build, Rick and John make guitar waves. They roll. They rise. They curl. They’re a fucking tsunami. And they crash as hard and fast and oddly tuneful as they began. How did they do it? Twelve years later. Nearing fifty. Seriously, how did they do it? How did they make a record that sounds both like a day of surfing and a thirty minute dead sprint? How were they still this cranky and that fun? How were they still kind of like “fuck it all” and “fuck yeah” at once?

“Jericho Sirens” was an unthinkable reunion -- if you can even call it that. It wasn’t anything like their forebears, The Replacements, who were only barely “The Mats” when they returned. That reunion was mostly a well-earned payday for Paul Westerberg, and a kindness to fans who did not care that there was no new material. In fact, that was how everyone wanted it. It wasn’t like The Pixies, who really were The Pixies but who didn’t want to be together and who made new music that nobody liked. It wasn’t like LCD Soundsystem, who maybe never actually broke up. And it wasn’t like Pavement, who probably didn’t need the hoopla but embraced the victory lap anyway. The return of Hot Snakes was an actual return. Or maybe it was just an unpause. Or maybe they never actually went anywhere. Along with AC/DC, The Feelies and, nearly, The Ramones, Hot Snakes were the rare band that never changed and were always perfect.

Between 2018 and 2020, Hot Snakes toured the world. They looked older but certainly didn’t sound it. John, who was approaching fifty, resembled a young Joe Strummer, after a Hawaiian vacation. Rick, meanwhile, was appropriately paler, but still somehow able to holler with perfect pitch. But, even then, with the tailwind of nostalgia, in those bigger venues, packed with the kids they loved to hate, Hot Snakes were “paid amateurs.” Obviously, there was nothing amateurish about the show. They were ferocious the night I saw them. But they were paid amateurs in the capitalistic sense -- in that they could never get paid what they truly deserved; and, perhaps, not as much as they needed.

Almost two decades after Hot Snakes were born, I wondered what had really changed. The kids were paying for music again, but they were renting rather than buying it. The worst human in the world was in the White House. But, also, the legends of John and Rick had only grown. “Jericho Sirens” came out in 2018, but it could have been 2001. I could have been cursing my broken down Vespa, Swami John could have been conjuring magic riffs and Cranky Rick could have been eating shit at a day job and completely destroying the Mercury Lounge by night.