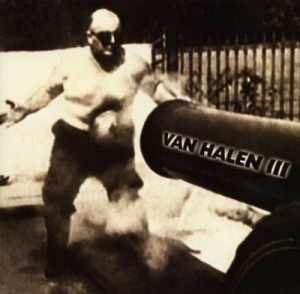

Van Halen “Van Halen III”

In 2003, I had no idea who Shaun White was. I did not snowboard and hadn’t touched a skateboard in fifteen years. Generally speaking, my ignorance should not have been a problem. Except for the fact that I was doing some work for Target (the red bullseye one) and one day found myself with their head of youth marketing, driving from Los Angeles to a TGI Fridays in San Diego to meet with the teenage board ninja. The meeting was really just a courtesy -- an informal check in between Target and the budding star that they sponsored. My presence was incidental, at best. So, while driving, I simply feigned familiarity with the double flip this and triple spin that while redirecting the conversation to the weather or the ocean or, really, anything else.

We eventually arrived at Fridays, got seated and were shortly joined by a diminutive, suburban mom, her similarly tiny, gangly son and his impossible head of hair. Still just a teenager, Shaun had a massive smile and a bad complexion. He looked like Leif Garrett mixed with Ron Weasley, but with more sunshine. My presence, though unexpected, didn’t hamper the conversation. I survived dinner intact and was fully prepared to leave until, just as the check arrived, my friend slash Target executive opened up her laptop and clicked play on a video reel of Shaun skating. I had no idea what the video was — whether it was a promotional thing or a documentary or something else. I had skated just a little bit as a tween. I’d, of course, seen Tony Hawk highlights, a couple Big Brother videos and the X-Games on MTV. But, this was something else. Shaun White didn’t skate like anyone that I’d seen before. He soared higher. He rotated more. And, mostly, he made it look so easy. Other skaters made the sport look breathtaking or exhilarating or death defying. Shaun White sort of did all of those things. But he also made it look positively natural. And really, really fun.

I racked my brain, trying to determine if I’d ever seen an athlete perform feats that were so obviously difficult with such apparent ease. There was something familiar about the sensation, but I couldn’t place it. Was it the way Ken Griffey Jr. swung the bat -- the grace, the ease, the power? Was it old footage of young Muhammed Ali, gliding and battering simultaneously? Was it Magic Johnson leading the fast break, delivering a perfect no-look pass to Worthy or Kareem for the finish? Was it the way each of those men excelled at their sports with that ultra-rare combination of aberrant skill and stylistic ease? Or was it the knowing, youthful grin they’d flash after victories?

The more I thought about it, though, the less convinced I was that the sensation was sports inspired. Soon, I began to picture another young man with long shaggy hair and gear attached to him like an appendage. As he came into focus, I saw him performing dazzling moves with uncanny dexterity. He was obviously a virtuoso, but there was also a playfulness that betrayed his skill. And then there was that toothy grin -- one part aww shucks humility, one part adolescent devilishness and one part Jack Daniels. As his image came into relief, I realized that I was not picturing an athlete at all. I was picturing a musician. I was picturing the musician who, more than any other, performed the most complicated feats in a manner that looked like the exact opposite of hard work. The more I thought of Shaun White and his Double McTwist 1260’s, the more I thought of Eddie Van Halen.

Though I grew up in the 1970s, I came of age in the 1980s. And so, I missed the first wave of Van Halen. When I hear Chuck Klosterman talk about what it felt like to first hear “Runnin’ with The Devil” or “Eruption” in 1977, I can only try to imagine. Similarly, I am not a musician. I’ve never played an entire song on the guitar. So, while I can intellectually understand the challenge of tapping and tremolo picking, the actual skill required is abstract to me. And, tellingly, I was never really a Metal guy or a Hard Rock guy. So I don’t view Sabbath or Zeppelin as personal, musical touchstones. But I suspect that my age and my lack of skills are almost irrelevant when it comes to Eddie Van Halen and his band. I didn’t need to know formal technique to know that it seemed impossible for one person to produce as many sounds as he did on guitar. I didn’t have to study the complete works of Jimmy Page or Randy Rhodes to appreciate a half Dutch, half Indonesian, fully Californian, out-muscling Clapton, out-imagining Hendrix, out-mathing Fripp and out-ballsing Angus and Malcolm Young. I understood that Eddie could have been ten Stevie Ray Vaughns or five Jeff Becks or three Brian Mays if he chose to. But, instead, he decided to be all of those guys. Because he could. And because it was fun for him.

More than their hit songs (only one of which reached the top of the charts) or their albums (most of which are considered uneven) or their legend (booze, drugs, girls, destruction and gossip), the magic of Van Halen lay in their uncanny ability to make the most difficult things look and sound playful. They did so like they were the house band for “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.” They did so like they were Will Hunting solving calculus for Dr. Gerald Lambeau and wondering why everyone else seemed to think that PHD-level math was so hard. Between 1977 and 1984, they did everything bigger, louder, faster, hornier and drunker than everyone else.

Eddie Van Halen was so good that, almost necessarily, he needed a carnival barker with a flat voice to provide constraints for the music. David Lee Roth was the inverse of Eddie -- limited skill, visibly showy and kind of obvious. With his squeals, wows, jokes, jumps and splits, Van Halen’s singer communicated what their guitarist simply implied -- that the band was performing at the highest possible levels, with the greatest of ease. No other Rock groups from the time had that alchemy. Zeppelin were mystical and inaccessible. Yes were for players and eggheads. AC/DC were repetitive. Boston, Foreigner and Journey were faceless. Sabbath were old and broken down. The Sex Pistols were pop art. Van Halen were none of those things but with all of those influences.

By “1984,” however, Van Halen were -- as much as anything -- Hollywood. Despite where they were born, they were fully California kids. They cut their teeth on Sunset Boulevard. They sprayed their hair and painted on their spandex. They were tan. And stoned. They were stars — more like Sly and Arnold (or Jeff Spicoli) than like Sting or Bono or Prince. They seemed sunny and naturally beautiful, but probably enhanced in some way. Plus, they exuded sex. As a ten year old in 1984, Van Halen videos were about as close as I got to pornography. Even decades later, I think that they were probably sexier than anything in the pages of “Playboy.” A generation of young men and women grew up loving Van Halen because of how they played and how they looked, but also because we were certain that they knew things and had done things that we could not know or do.

My proof point for all of this was not “Runnin’ with The Devil” or “Pretty Woman” or “Dance the Night Away” or, even, “Jump” or “Panama.” No -- my case rested squarely on the shoulders of “Hot for Teacher.” It was all there in that song and its video. The playing is like a rollercoaster from the next millennium -- tight, loud and ultra-fast, but with a singalong chorus and locker room banter. The video, meanwhile, is like an 80s update on a 60s cabaret show, as directed by a lead singer who was both too smart and too horny for his own good. To see and hear it as a ten year old boy was to learn everything I needed to know about Van Halen. They were never my favorite, but, objectively -- and certainly at that moment -- they were the greatest.

No matter how much you love or defend Sammy Hagar or how much you count platinum records and hit songs, everything that followed “1984” was downhill. It wasn’t simply the infighting or the booze or drugs. It wasn’t the tawdry gossip. It wasn’t that “Why Can’t This be Love” was a bad song or that the players suddenly lost their faculties. It’s that what made Van Halen great was no longer so apparent. Their weirdness got sanded away. They wore golf shirts. Their music began to resemble that of Bon Jovi and Def Leppard and White Snake and a generation of Van Halen acolytes. They started to look -- and sound -- like adults. Sammy Hagar sure could sing. But he looked like a San Diego surfer, not a Hollywood star. Moreover, when he sang, you could tell how hard he was trying. Dave was a ham. But Sammy was a howler. He had to reach down and use his diaphragm and really push those songs out. On stage, it still looked a little bit like fun. But, increasingly it also looked like serious work. The “Hot For Teacher” video had the band in prom suits ogling bikini-clad teachers. The video for “Right Now” had black and white stills with captions about the plight of the world. It had only been seven years since “1984,” but it felt like a lifetime ago.

Those first betrayals -- the departure of DLR and the slow death of their playfulness -- may not have been terminal. I suspect that we could have even survived the new step dad. Van Hagar has plenty of critics, but they also sold tens of millions of records. In fact, they had four straight number one albums. And, perhaps most importantly, Sammy wasn’t trying to replace Dave. He was already a star in his own right. Not Van Halen level stardom, but the secure-in-his-shoes sort. By the end of the 80s, Boomers and their kids were familiar to the point of comfortable with divorce. Sure, it got nasty at times. But c'est la vie. We didn’t wish for Dave’s failed acting career. We didn’t wish for his failed solo career. In the heyday of Guns N Roses, the Hagar vs. Roth headlines seemed completely normal — almost quaint.

While we accepted Dave’s departure and bought the Hagar albums, both the Rothophiles and the Hagarites recoiled when Eddie invited Dave back into the band and then recanted the offer. We were all OK with one divorce. We rolled our eyes a bit at the step-dad but we tolerated him and secretly liked him. We even understood the second divorce. Things happen. People grow up and cut their hair and take up golf. But the 1996 almost reunion and the ensuing PR stunts were not OK. And the ensuing addition of Gary Cherone — the guy from Extreme — was so completely not OK that by the end of 1996, the Van Nation was up in arms.

Gary Cherone never had a chance. He was the second step dad for a generation of adults who didn’t want another step dad. He provided no obvious counterbalance to Eddie or Alex. And aside from a pretty, but flaccid, hit in 1991, there was scant evidence of his greatness. He was undoubtedly a gifted singer, but the world was full of gifted singers. Anyone who still cared about Van Halen in 1996 quickly sized him up as 80% Sammy and 0% Dave. It was a formula that exactly nobody was buying. Moreover, Cherone’s arrival signaled deeper dysfunction -- the inability for Eddie and Alex to keep their shit together. Rumors of Michael Anthony’s imminent departure only confirmed those suspicions. With whispers of Eddie’s alcoholism becoming more brazen, Van Halen no longer sounded like virtuosos having fun. They were beginning to sound like talent wasted.

By all accounts, Cherone wanted to ease his way in. He rightly suspected that fans needed a “get to know you” period, and, frankly, so did he. His hope, it seems, was for the band to tour, gel, and practice before they recorded. But he was not afforded that benefit. Cherone joined the band in late 1996, was in the studio in early 1997, and, in spite of several attempts by the label to send the album back, “Van Halen III” was released in March 1998. If Cherone’s introduction seemed doomed, rest assured that the album itself was far worse.

At this point, it’s almost a cliche to say that “III” is the worst Van Halen record. It has very few defenders. In that way, it can feel lazy to pile on. But also, most people -- including most Van Halen fans -- have not actually heard the entire album. It’s a wayward stepchild that fans barely acknowledge. To many, it's simply “the Gary Cherone record” — as if that sufficiently sums up its awfulness. However, as somebody without much investment in the legacy of Van Halen, I was always curious. “Could it really be that bad?” I wondered. “Is it cheesy or painful or just a step down from Hagar?” “Did they try Nu Metal?” For a quarter century, I occasionally wondered about the mythic Van Horrible album. But ultimately, not enough to ever buy, borrow or steal a copy of “III.”

With Chuck Klosterman’s recent book about the 90s, though, I found myself thinking about what happened between Van Halen with Dave and Van Halen with Sammy. And, once I started out on that trail, I couldn’t just stop. It wasn’t the end. Van Hagar wasn’t even close to the end. There were more tours. There was the post Michael Anthony, Wolfgang Van Halen era. There was the Hagar reunion and the eventual, more celebrated reunion with Dave. So, while there was only one new album in the 2000s, there was actually a lot of history after 1996. And, no matter how hard we tried to deny it, Gary Cherone was Van Halen’s lead singer for about three years of that history. It really happened. And I had to know what it actually sounded like. The more reviews and comments I read about “Van Halen III,'' the more I wanted to run far away from the album. And, also, the more I knew that I absolutely needed to hear it.

To the surprise of absolutely no one, I can confirm, after many listens, that those warnings were well founded. “Van Halen III is almost uniformly terrible. At sixty-five minutes run time, it is also the longest Van Halen record. By comparison, the first six Van Halen albums, all with Dave, averaged under thirty five minutes in length. The Hagar albums had more girth -- “Balance” bloviated for about fifty minutes. But, it also produced three top ten Rock radio hits. If you remove the two little instrumentals from “III,” which are about ninety seconds each, then you are left with ten tracks, averaging over six minutes in length.

While there are solos all over this record, its length has almost nothing to do with improvisation or dynamics or jazz. The bloat is mostly on account of a complete absence of structure. Very few of the tracks on “III” resemble anything that we’d consider a “song,” much less a “Van Halen song,” much less a “good Van Halen song.” Eddie hyperfunctions, throwing riffs on top of hooks on top of lines on top of jams. But rarely do we get anything close to a sustained melody or a memorable chorus. Warner Brothers reportedly rejected the album on numerous occasions and, while I am not one to normally side with the A&R team over the brilliant, iconic musicians, in this case the label was right.

“Without You,” was the album’s first single -- radio’s introduction to Van Halen with Gary Cherone. It is also six and half minutes of quarter baked, Nu Metal riffs working against a singer imitating Sammy Hagar imitating Fred Durst. Alex just aimlessly pounds away, while Eddie exhausts himself trying to find the song amid the grating noise. It’s the second track on the album. It follows “Neworld,” which is, frankly, a very pretty — almost Baroque —instrumental featuring just guitar and piano. It sounds like a little English Folk idea that Ian Anderson and Martin Barre might have kicked around in 1974. Or like a tasty amuse bouche that briefly entices you before the shit stew that follows. “Without You” comes after the amuse bouche. It is the first course in a feast of Heavy shit stew. Two songs in, you’re already overstuffed and kind of nauseous.

The album’s other singles are no better. Beyond their lack of pleasure, however, is the mystery of how or why the band thought that radio programmers would respond to them at a time when Tracy Chapman, Natalie Merchant, Melissa Etheridge and Hootie were atop the Rock and Pop charts. On “One I Want,” Eddie takes a nifty Angus Young idea and then heaps a half dozen, lesser but louder ideas on top of the hook while Gary screams about how he loves his woman the way a pizza man loves pizza. “Fire in the Hole” opens with the sound of a helicopter and a titanic riff. For a few moments, you expect Alex to steady the band and build some propulsion. But it never comes. Eddie just gets in the way of himself -- freestyling and overseasoning instead of settling into the song. The result is screechy Metal -- the sort of thing you might expect from Warrant or Stryper or W.A.S.P. But, not from Van Halen.

In part due to the new singer, but mostly because of Eddie’s manic compositions, “III” sounds like a lot of Heavy Metal and Hard Rock bands not named Van Halen. “Josephina” tries out something proggy on the acoustic guitar which could pass for overcooked Queensrÿche. “Ballot or the Bullet” sounds like something from the bottom of the New Wave of English Metal. And “Once” is a batshit crazy, Heavy Adult Contemporary track that feels like a hornier version of Toto with Gary Cherone as it’s lead singer. Amazingly, it almost hits a new, campy high mark. There’s even a moment where you think it might make a turn towards Jim Steinman melodrama. But, without sufficient melody, it misses, and then keeps on missing for over seven minutes. Somehow -- along with the instrumentals and the mostly uninteresting “Dirty Water Dog -- “Once” is among the most tolerable songs on the album.

Famously (notoriously), “Van Halen III” closes with “How Many Say I” — a piano ballad written and sung by Eddie Van Halen. It is the only Van Halen song that Eddie sings lead on -- and for good reason. Like Keith Richards, Eddie can be a lovable harmonist. And, like Keith, his voice is weathered and limited, to the point of being weak. But, unlike Keith, Eddie’s voice has zero charm. It doesn’t sound wise or bluesy or heartfelt. It sounds weak and off key. Additionally, he’s simply not capable of writing the lyrics that offset the cost of his voice. Eddie could play circles around Keith, but he was no poet. He could never write “Happy,” or “Memory Motel” or “Before They Make Me Run.” Instead of gutting out something sad but beautiful, like Keith occasionally does, Eddie cautiously -- almost shamefully -- ends to the misery of “III” with more misery:

Have you ever looked down when the homeless walked by?

Or changed the channel when you saw a hungry child?

Know something to be true, then deny it

How many, how many, say I

Wholly on account of their legacy, all three singles from this album charted. Their ascent was extraordinarily brief and, then, they were violently forgotten. In their wake, “Van Halen III” became the album of which fans do not speak, except to laugh at. Cherone was an easy target, but “III” is functionally an Eddie Van Halen solo record. Eddie played bass on most of the album, all the guitars, all of the piano, synths and some drums. He also co-produced with Mike Post, who was not even known to be a producer of Rock music but was a composer celebrated for his work on “Magnum P.I.,” “L.A. Law,” “NYPD Blue,” “The A-Team” and, not coincidentally, Eddie’s favorite show, “Law and Order.”

Many great guitarists before Eddie struggled as solo artists. Jimmy Page comes to mind. He’s an easy target. But Brian May, Joe Perry, David Gilmour, Neal Schon, Pete Townshend and countless others have foundered as frontmen where they flourished as lead guitarists. In the broadest terms, Eddie Van Halen fits into that esteemed group. He’s an exception, though, in that his skill probably exceeded all of those men, as did the joy with which he initially played, as did the force with which he ultimately bottomed out.

For almost four years, between 1999 and 2003, Van Halen went away. Michael Anthony was officially relieved of his duties. Eddie had hip surgery. He also was treated for tongue cancer. Then there was something between a dalliance and a reunion with Hagar. Then Sammy left again. Then there were rumors of Dave’s return. Then there was long overdue rehab for Eddie. Meanwhile, Dave had been a disc jockey, a cabaret singer and an EMT. While Van Halen’s future prospects were uncertain, Dave’s were most certainly grim. Until 2010, when, finally, David Lee Roth rejoined Van Halen.

Though a lot of his hair was gone and his star faded, in 2010, Dave was still basically the same guy -- hammy, whip smart, hard to follow, big mouthed, attention starved and attention deficient. Eddie, however, was changed. He was more clear eyed, more articulate, slower and slightly hunched. That year, Van Halen, with David Lee Roth on lead vocals, started recording “A Different Kind of Truth.” The album, which featured compositions originally drafted in the 1970s alongside brand new ideas, was released in 2012 to considerable fanfare and great critical acclaim.

In support of their final album, Eddie, Alex and Dave got together for a series of conversations, filmed in black and white. Appropriately, Dave operated as emcee for the promotional videos. He asked the brothers about growing up in The Netherlands and those legendary, early shows at Gazzarri's and their delirious 70s ascent. In many ways, the conversations feel contrived. It’s plain that they’re marketing objects. Plus, the dynamic is imbalanced. Dave requires too much oxygen. Eddie’s words lag behind his thoughts. And, all the while, Alex just waits his turn. But, the more I watched, the more familiar it seemed. Dave’s cackle. Eddie rolling his eyes in a mischievous way. Alex translating from the middle. On the one hand, it seems impossible to condense forty years into a thirty minute electronic press kit. Especially when the history is so fraught. Especially when the facts are contested. But, somehow, they did it. Because that’s what Eddie Van Halen did. In spite of everything, he made the impossible look kind of easy. And Dave made it look fun.