Jim Palmer “The Unnatural”

In early 1985, less than a year after Jim Palmer retired from baseball, Jim Brown was still pissed off. His anger had nothing to do with Palmer, of course. It was mostly directed at Franco Harris, the Pittsburgh Steeler great who had inched too closely to the NFL’s all-time rushing record. Whereas the most dominant player in football history had run past and through defenders, Brown asserted that Harris was stumbling forward, three yards at a time, avoiding contact, in his pursuit of history. The idea of being surpassed by a lesser athlete was so galling to Brown, in fact, that he actually considered unretiring and returning to the NFL at the age of forty-seven.

As it happened, Harris never caught Brown. He retired in 1984, less than two hundred yards short of the record. But Brown could not let it go. And so, on Super Bowl weekend in 1985, he competed against Harris in a four sport, nationally televised competition called “I Challenge You.” Brown wiped the racquetball court with Harris to take the first event. Next, he staged a comeback to win the one on one basketball event. Phil Simms was brought in to quarterback a pass catching competition, which Harris took. Up two events to one, all eyes were on the finale -- the forty yard dash. The winner of this race would be crowned champion of the challenge.

Brown looked fit and ferocious at the mark. However, when the starter’s shot was fired, it was immediately clear that something was wrong. Harris won easily, lumbering his was to a 5.16 time -- a pace eclipsed by most three hundred pound offensive lineman today. Brown crossed the line at 5.72 seconds, pulling at his hamstring, but making no excuses. As champion, Franco won a car and a camper. Brown took home a mink coat and $15,000. Though he’d competed admirably, even stunningly at times, Brown understood his age. He never talked about coming back again.

That same year, in Texas, thirty eight year old Nolan Ryan was showing signs of wear. He lost more games than he won and posted the single highest ERA of his career. But, miraculously, just two years later, something changed. From 1987 until 1990, from the age of forty until he was forty three, Ryan led the league in strikeouts every year, averaging over ten K’s per nine innings and topping three hundred during the 1989 season. In 1990, he threw a fourteen strikeout no-hitter. And, the next year, at the age of forty-four, he did it again. Zero hits. Sixteen K’s.

While Jim Brown was challenging Franco Harris and while Nolan Ryan was humiliating Robin Ventura, Jim Palmer was broadcasting with Al Michaels, raising tons of money for charity and doing the things he’d long excelled at -- playing golf and modeling underwear. However, after the 1990 season, when ESPN asked him to take a pay cut, he balked. He’d spent nearly two decades in the majors leagues, feeling financially aggrieved in the face of his unmistakable greatness. In 1975, when he won his second Cy Young award he received a paltry fifteen thousand dollar bonus. When the Orioles won the World Series in 1970, each player’s share was less than that amount. In 1990, Roger Clemens, the runner up for the AL Cy Young award, earned two point six million dollars.

As interested as he was in money, however, Palmer wasn’t entirely motivated by it. It is possible that he’d spent his early retirement considering what Jim Brown had said and done in 1985. It’s more likely, though, that he thought about Nolan Ryan and George Blanda and Gordie Howe, all of whom played well into their forties. It’s conceivable that he was bored in the broadcast booth. Or that he felt he had unfinished business. Or that the Orioles, who had been the winningest team in baseball during Palmer’s career but who had bottomed out shortly afterwards, were in need of a veteran arm. Whatever the motivation, Palmer had made up his mind. In 1991, at the age of forty five and almost seven years removed from his final game, he was going to come back.

In 1990, during his first year of eligibility, Jim Palmer was elected to the baseball Hall of Fame. He sat alongside his former teammates, Brooks and Frank Robinson, and got to soak in the moment near his heroes, Ted Williams and Stan Musial. The following spring, however, he was the longest of longshots at training camp for the Baltimore Orioles. Even in middle-age, Palmer was still the picture of health. He looked lean and strong and movie star handsome -- just like he always had. Rookies stared at him while photographers clicked away. It wasn’t exactly “The Natural,” but Palmer was not too far from Redford and, as stories go, this had the potential to be a great one.

As spring training arrived, however, Palmer was keeping a secret. His fastball was stuck in the low eighties. He was still a long six foot, three inches and a svelte one hundred and ninety pounds. His delivery still featured that unusually high leg kick and elongated throwing motion. But the velocity never came. He politely smiled for the press. He got to pal around with his buddies and former teammates, Cal Ripken Jr. and Mike Flanagan. But when he was called to take the mound, the truth was revealed. He let up five hits and two runs in two innings. And then he heard something pop in his leg. He was forty-five years old. He didn’t have it any more. In less than an hour, the comeback was done.

Throughout the history of baseball, the retirement of a legend was completely logical. The unretirement, however, was almost unprecedented. Though he had been accused of vanity during his playing days, Palmer was more so known to be exceedingly logical and cerebral. So, what prompted the greatest pitcher in Orioles’ history -- arguably the best pitcher of his era -- to defy logic? Well, that's a very long and complicated story that starts in New York City, way back in 1945. It's the story of a boy who believed that, with hard work and good behavior, anything was possible. And, for the better part of forty years, he was correct.

Jim Palmer was born in Manhattan to birth parents who remained unknown and under circumstances that remained unclear for over seventy years. He was adopted at two days old by an affluent couple who resided on Park Avenue. In 1955, Palmer’s father, Moe Wiesen, died suddenly of a heart attack. A year later, however, his mother remarried Max Palmer, a television actor slash shoe salesman. The Palmer family soon relocated to California and, then, eventually, Arizona. When he arrived on the west coast, Jim Wiesen was a lanky ten year old with no specific sports accomplishments. Within five years, however, he was Jim Palmer -- a three sport varsity letterman who soon became an all-state athlete and blue chip prospect in baseball, basketball and football. By the age of eighteen, Palmer was dominating the minor leagues. The next year, he was pitching in the majors. And, in 1966, at the age of twenty, he shut out the Dodgers in the World Series, defeating Sandy Koufax in the final game of his career.

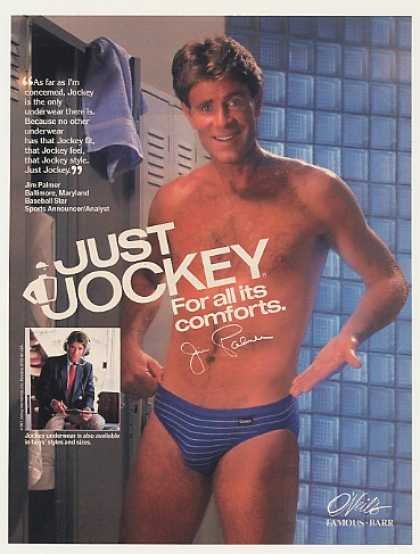

To the casual observer, the next two decades could read like a fairy tale. Palmer won three World Series titles and three Cy Young awards. He won more games than any other pitcher in the 1970s and retired with the fourth lowest ERA of the modern era. He won twenty games eight times in ten seasons. In 1975, he threw ten shutouts -- a feat that is unlikely to ever be matched again. He started his career with two bonafide legends -- Brooks and Frank Robinson -- and bookended it with a World Series title in 1983, alongside two, younger Hall of Famers -- Cal Ripken Jr. and Eddie Murray. In between, Palmer became a national sex symbol, representing Jockey brand underwear and thrilling millions of women (and men) of a certain age. He was the kind of guy who would have been undefeated on “The Dating Game.” He was a Ken Doll in a baseball uniform, with bikini briefs underneath. In almost every imaginable way, Jim Palmer was the Prince Charming of baseball. At least, that’s how it seemed outside of Baltimore.

If you lived in Maryland or Washington D.C. or followed baseball closely, however, there was another story, with conflicting subplots and less sympathetic narrators. From the late 1960s, until he retired, if you asked Orioles fans or players -- and especially if you asked the team’s manager, Earl Weaver -- you got the other perspective: Palmer was a prima donna. Palmer had a superiority complex. Palmer was a hypochondriac. Palmer was obsessive to a fault. The underside of the fairy tale was a story of privilege and hubris. It is, of course, well documented that Palmer was unabashed in his disagreements with Earl Weaver. He frequently and publicly disagreed with his manager’s decisions, suggesting that they were either uninformed or simply incorrect. He’d overrule coaches and move the defense around based on what he knew about the opponent. When teammates would make blunders in the field, he’d respond with something in between disappointment and disdain.

In retrospect, Palmer’s origin story, his evident intellect and his good looks did him no favors. Playing for a blue collar manager in a blue collar city, many of his “finer qualities” were resented, but tolerated. He was booed when he underperformed. He was publicly shamed when he complained (as he often did) about arm or back pain. His Jockey underwear ads inspired eye rolls. And yet, he was the workhorse. He averaged nearly three hundred innings per season during the 1970s. He completed nearly twenty games per season. And the Orioles kept on winning. So, even if he was a complainer -- even if he was a prima donna -- he was their complainer. He was the prima donna of champions.

Moreover, he had literally come from nothing. He had worked tirelessly along the way. He looked like a natural -- like “The Natural” -- but he was constantly striving. He was sent down to the minors in 1967, just one year after he won fifteen games. He considered retirement at the age of twenty two. In 1969, during the league’s expansion draft, when Palmer was in double A and when any of the new franchises could have selected him, he was passed up. That season, having dealt with his arm issues, he returned to the bigs and won sixteen games while losing only four. Several times during his career -- after he faltered and after his injury claims were doubted and after fans turned against him -- he returned to dominant form. When he was right, he made it look so easy. But, anyone who followed the game knew the truth about Jim Palmer: everything required work. Constant work. Hard work. Team work.

In retirement, as a broadcaster, Palmer confirmed many of the things that we assumed about him. He was telegenic. He was soft and carefully spoken, but also highly opinionated. Above all, he had an abiding sense of what was required to win and, conversely, why teams and players fail. Which brings us back to the comeback of 1991. Why? Why did he do it? Did he genuinely believe he could? Did we believe it? Did he believe it because we believed it?

Jim Palmer was forty-five during the comeback but looked thirty-five. He was, in fact, likely in better shape than most of the twenty-five year olds at camp. So there was that. But, moreover, he’d spent a lifetime beating the odds. From birth, through that first demotion in the sixties, through the injuries and the boos, he returned each time, and better than the last time. His second marriage outlasted his first one, which was pretty successful in its own right. He even had an amicable divorce! Jim Palmer had been good at everything he’d ever done, but especially at coming back.

Today, in the second half of his seventies, he remains remarkably fit and handsome. There are many more lines around his pale blue eyes, but he has a full head of (store bought) brown hair and looks like a guy who could throw a no hitter in an over sixty league. Onscreen he remains sharp and articulate. Though his words roll out gracefully, his mind appears to be in constant motion, tempered only by a strict sense of right and wrong.

Compared with twenty-first century sports grievances, Palmer’s 1970s objections sound almost quaint. While he may have been the most vocal critic of his manager as a player, he has also been loyal to the Orioles franchise for over fifty years. Many sports writers have suggested that Palmer is opaque -- a set of walking contradictions. That he is equally smart, virtuous and kind as he is overconfident, indignant and selfish. In 1996, he wrote a book about his career alongside Earl Weaver entitled “Together We Were Eleven Foot Nine.” The book title is at once a statement of facts, a series of digs and a loving acknowledgment of the contribution of others. So, whether or not Palmer is knowable, it seems that he knows more than a little about himself.

For many of us, the hardest part of aging is confronting our limitations after decades of surpassing them. Some of us resist and stumble painfully. Others take it as an existential failure and find it crippling. Meanwhile, the lucky ones accept the change, learn and adapt. Jim Palmer likely resisted failure more than most. He was, after all, a wildly successful professional athlete. He was the guy who, after he couldn’t lift his arm and after he refused cortisone and in spite of being called a whiner by his manager and teammates, still completed games and pitched shutout after shutout. In his childhood, Palmer was a die hard Yankees fan. During his career, he faced Mickey Mantle nine times and, decades later, Don Mattingly three times. Combined, the Yankee greats mustered just one hit against Palmer -- a sub one hundred average.

If it were almost anyone else, the idea of a comeback to baseball at forty five would seem like vanity or self delusion. With Palmer, it was certainly part that. But it was also somewhat rational. It was a rigorous test, not unlike others he’d passed before. Only, this time his hypothesis proved invalid. And so, afterwards, he did the next best logical thing. He went back to the what he was great at -- calling ballgames, playing golf, raising money for charity and exciting middle-aged women.