John Hiatt “Perfectly Good Guitar”

There’s a concept in child rearing — and I’m honestly not sure if it’s armchair psychology or actual science or something in between — called “perfectly adequate” parenting. Its premise is radically simple: that parents should be no more or no less than their child needs. Provide love, food and shelter. Be there when they need you and not when they don’t. Answer when asked but don’t preach. Create safe environments for them to try and fail but don’t solve all their problems for us. The concept, which dates back to the middle part of the twentieth century, made a return to the zeitgeist when it was in conversation with Jennifer Senior’s “All Joy and No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenthood.” It’s by no means a new idea. But, in comparison to the hyper/hover-parenting of today, perfectly adequate parenting can sound downright revolutionary.

In many ways, perfectly adequate parenting seems logical. Don’t overburden your kids with your bullshit. Don’t try to fix everything. Don’t spoil them. But also, show up. The theory suggests that somewhere in between too much and too little parenting, is a lower cost, higher upside path to healthy childhood development and sustainable parental relationships.

On the other hand, nobody really wants to be “perfectly adequate.” Not in parenting. Not in life. Not in work. And, certainly, not in music. Nobody dreams of being a perfectly adequate songwriter. Or singer. People don’t start a band hoping that they are not too much or too little (well, maybe Matchbox Twenty). Pop music is defined by highs and lows. By opulence and restraint. By mania and soul. All too often, however, those binaries lead to crap or flameout or both. The road in between is longer. And oftentimes much harder. It requires grit. And consistency. And longevity. It’s a workmanlike path. It’s the path of a compiler — somebody whose greatness is revealed over time and through tireless effort. It’s the path that is rarely disruptive or revelatory, but is eventually, and amazingly, just right.

Or sometimes better. Richard Thompson is always perfectly adequate. Sometimes more. Sometimes much much more. But never any less. The second half of Van Morrison’s career has been, for the most part and notwithstanding his heel turn, perfectly adequate. John Prine. Lyle Lovett. Nick Lowe. Always perfectly adequate. Rarely any less. Of all the singers I can think of, however, the one who is most truly perfectly adequate — whose skill is evident, whose records are solid, whose craft is undeniable and whose commitment is unwavering — is John Hiatt.

Now, you might protest. You might even be insulted. You might be thinking: “You are out of your mind — John Hiatt is a legend!” “John Hiatt is an elite songwriter!” “John Hiatt has made many superb albums!” To which I would respond, “No.” “Probably.” And “Really?” But also, let me be clear. I mean this as high praise. John Hiatt is beloved but not a legend. In fact, his appeal is, in part, his sub-popularity. And yes, he has written hundreds of songs, many of which are wonderful and almost all of which are sturdy and tuneful. But very few are timeless or essential. And as for those albums, they are always worthwhile. They are occasionally much more than that. But there is no masterpiece. There is just slightly better and slightly worse.

To the uninitiated, John Hiatt is hard to describe. He is soulful, but he’s not mystical like Van Morrison. He’s bluesy, but not deeply so, like Clapton, or incendiary like Stevie Ray. He’s highly literate, but almost never literary like Randy Newman or Warren Zevon. His songs are genre-bending, but not genre-pushing like Wilco. And though his former record label spent a lot of time and money trying to convince us otherwise, he was never nervy enough to be America’s Elvis Costello or Graham Parker. There are dozens of singers who Hiatt sounds like, and yet, his voice is almost instantly recognizable. Like I said, he’s hard to describe.

It’s a strange quality — to be so stylistically diffuse and yet so distinctly familiar. It’s a testament to the songwriter that he is able to assimilate so many influences into one cogent sound. Hiatt’s musical stew simmers. It has its own flavor. But it’s also comforting. It’s very American. In fact, it’s probably closer to the Heartland Rock than Bruce or Bon Jovi or Petty. Like John Hiatt, John Mellencamp was from Indiana. But, growing up, Mellencamp was a singer in a Glam Punk band who really wanted to be an abstract painter. So, yeah, John Hiatt is more Heartland than John Mellencamp. Oddly, though, he’s as “All American” as he is “Anti-Establishment.” In almost every sense, he’s exists somewhere in a highly competent “in between.” It’s a tough position in a market that rewards exceptionalism and binaries.

Hiatt had good reason for angst — to resist the high middle road. As a child, his older brother — his boyhood hero — committed suicide. Two years later, his father, distraught and unwell, died. The first decade of his career was a series of fits and starts. After a spell writing on Nashville’s Music Row, he began to release a series of commercially ignored albums sandwiched in between the occasional minor hits he wrote for others. For many years, it felt like John Hiatt was the guy who everybody wanted to “happen” but who never would. Labels didn’t know whether he was a singer-songwriter, a bluesy rocker or a could-be-new-waver. It turned out that — in spite of some critical praise and industry buzz — the answer was none of the above.

By the early Eighties Hiatt began to bottom out, dropped from his record label, and exhausted from the downward spiral of coke and the booze and unfulfilled potential. His bottom was gradual, but his rebound less so. In 1984, he finally got sober, a feat which was supremely hard to keep when — just a year later — his ex-wife committed suicide. But then, after getting sober and mourning, at the moment that he finally stopped trying quite so hard, John Hiatt found release.

In 1987, having recently been dropped by Geffen Records and signed by A&M, he entered the studio flanked by Nick Lowe on bass, Ry Cooder on guitar, and Jim Keltner on drums — a veritable supergroup — to make “Bring the Family.” “Bring the Family” was about as good as perfectly adequate gets. It was a modest hit, peaking at 107 on the sales charts and featuring “Thing Called Love” (a hit for Bonnie Raitt two years later) and “Have a Little Faith in Me,” a soulful piano ballad which would go on to be covered dozens of times and serve as Hiatt’s calling card.

On its own, and in spite of its many renditions, “Have a Little Faith in Me” is nothing spectacular. It’s not breathtaking like Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” or undeniable like Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London.” It’s an excellent vocal performance from a singer who excelled in character more than quality. And, to be clear, that character was still less memorable than Tom Waits, Kris Kristofferson, Neil Young, Stevie Ray Vaughn or the countless others that Hiatt has been compared with. In fact, “Have a Little Faith in Me” succeeds less because of its musical greatness and more because of its honesty. It’s the story of a man staring down the second half, slowly but surely believing in himself as he senses that we believe in him. It’s a sublime tautology — we believe in him because he believes in himself and he believes in himself because we believe in him.

On some level, faith is the other side of acceptance. And “Bring the Family” was Hiatt’s album of acceptance, kickstarting a career renaissance for an artist who’d been a could be, a has been, a cult artist, a sub-popular artist and, finally, a semi-popular artist. By the late Eighties, before Grunge, “semi-popular” was synonymous with “Alternative.” In this way, and at this moment, Hiatt was actually much closer to The Replacements or even The Pixies, than he was to The Boss or Petty. As a result, in 1993, when there was news of a noisier, grungier, alt-ier John Hiatt album, it kind of made sense.

1993 was still the morning of Alternative Rock. It was a hey day for Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Smashing Pumpkins, Alice in Chains and Stone Temple Pilots. But, right behind them were lighter, less alternative hitmakers like Gin Blossoms, Soul Asylum, Cracker and Counting Crows. And while “Perfectly Good Guitar,” John Hiatt’s eleventh studio album was teased as closer to the former, heavier cohort, it landed much closer to the later bands, all of whom were at least partially inspired by Hiatt and who were closer to Heartland Rock than Alt Rock.

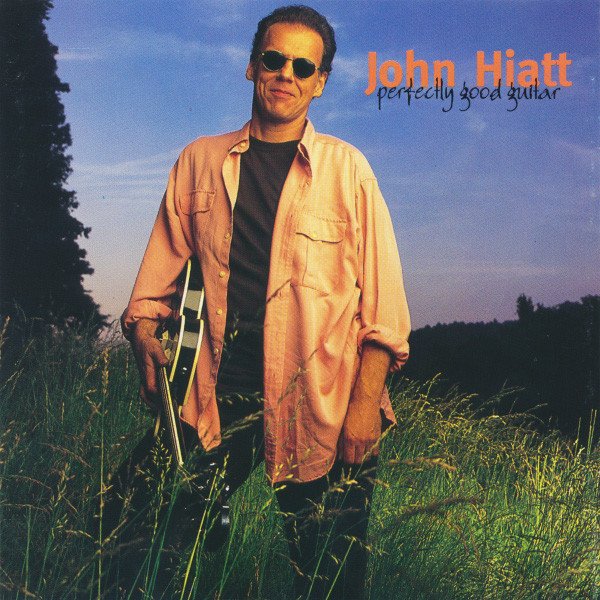

Even before the first note of “Perfectly Good Guitar,” you know it’s not going to be that heavy or that different from Hiatt’s previous records. The cover photo features the singer and his guitar standing in a field of tall grass. Hiatt is wearing jeans, a dark tee shirt and a coral colored shirt with a collar, unbuttoned and with sleeves rolled up. He’s smiling — or comfortably smirking. He’s neither weird nor defiant. And he’s clearly not angsty.

Despite the extra squeal in the lead guitar, the weight of the bass and the bite of the snare drums, “Perfectly Good Guitar” is a consummate, perfectly adequate John Hiatt album. “Something Wild,” which opens the album, and was later covered by Iggy Pop, is a mostly forgotten gem that splits the difference between ZZ Top and The Gin Blossoms. The guitar solos are short, but downright adventurous, while the rest of the song stays close to the loud jangle and muscular bass that propels the melody. It drives fast, straight and pretty loud — at least by Hiatt standards. It’s also the best thing on the record — the sort of song that, after one listen, you can sing along with.

Two songs later, he title track is both an homage to Pete Townshend and Kurt Cobain and a love song about an instrument. Without Hiatt’s vocals, it could be easily confused with any number of Neil Young and Crazy Horse songs — heavy rhythm guitar and a bottom that boils more than it cooks. But with Hiatt singing, it sounds almost parodic, like the old guy reprimanding the younger guys for a lack of decorum. But the tune doesn’t get lost in the message or the feedback. Like most of his songs, it all goes down easily.

Hiatt excels at many things, but the subtle ease of his melodies is a rare gift. None of his songs sound all that complicated. He’s never showy. You get the feeling that he could write dozens more just like the last one if he tried. But then, if you go and listen to his peers (Delbert McClinton, Joe Ely, Robert Earl Keen, Alejandro Escovedo, etc.) or those he influenced (Counting Crows, Gin Blossoms, Joe Henry, Marc Cohn) you quickly realize that their stuff lacks the effortlessness and the consistency of Hiatt’s music.

Despite his uncanny goodness, however, not all of John Hiatt’s songs are the same. Nor are they equally, perfectly adequate. “Straight Out of Time” is elite, Nineties Rom Com Power Pop — The Posies and Jellyfish and The Rembrandts would be proud to claim this as their own. “Cross My Fingers” has the crunch of late Replacements, except without Westerberg’s rasp and self-destruction. And “Permanent Hurt” is spiritually bruised but melodically sweet in the way that many Nick Lowe (or John Hiatt) songs can be. It just jangles and merrily rolls along, over and through the heartache.

Throughout “Perfectly Good Guitar,” when Hiatt injects his Hard Rock energy into his Heartland Rock, things are generally fine. The affect doesn’t ruin the compositions. Instead, they just sound like John Hiatt songs with a funny 90s haircut or an oversized Chandler Bing shirt and blazer. Their cores, however, are undisturbed. When he gets weirder though, closer to actual Alternative Rock, he sounds misplaced. “Angel” is upbeat and skittish — sunny like The Gin Blossoms but repetitive like Everclear. It’s too much too fast for a guy who, deep down, is a Soul singer. By the end of the track, Hiatt sounds out of breath.

There’s barely a clunker on “Perfectly Good Guitar.” "The Wreck of the Barbie Ferrari" is neither fast nor gruesome not is it effective satire. But it’s got a hell of a melody. Time and again, Hiatt excels hard fought resignation and hard earned faith. The other stuff — while perhaps forced or unnatural — is still still obviously competent and plenty likable.

Amazingly, it’s been thirty years since “Perfectly Good Guitar.” Thirty years of respectful four star, B+ album reviews. Thirty years of solid sellers, full of excellent songs and zero hits. Of Grammy nominations but no wins. Of NPR interviews and No Depression name checks. Of sobriety. Of watching his kids become adults. Of less hair. Of more lines on his face. Of looking more writerly but sounding the same. Of being perfectly adequate, in the best possible ways.