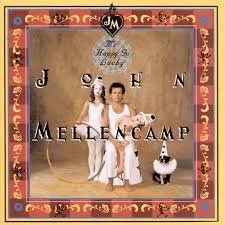

John Mellencamp “Mr. Happy Go Lucky”

He gave us so much. He gave us “Jack and Diane,” “Hurts So Good,” “Pink Houses” and almost a dozen other really good songs that I forget about until I hear them and think, “Oh yeah. Really good!”. He gave us Farm Aid. He gave us Meshell Ndegeocello. He gave us his German Expressionist portraits.

And then, in 1994, he gave us all a little scare when it was reported that he had a heart attack, brought on by a four pack a day habit. It was a fair moment to wonder whether that was it for John Mellencamp. He was forty-three, beloved in the Heartlands, had a hell of a run on the charts, a bunch of kids and a supermodel for a wife. By almost any standard, an early retirement would have been well-earned. But also, it was never totally clear what John Mellencamp’s legacy might be. Would he be the “Jack and Diane” guy? The “Pink Houses” guy? Bruce Springsteen lite? Was Mellencamp an overrated heavyweight or an underrated middleweight? Would he even be remembered at all?

In recent years, it has been suggested that Mellencamp should be remembered as a troubadour and an early influence on the No Depression scene. It is certainly true that Mellencamp brought the fiddle back into popular Rock music and that he shares some DNA with Steve Earle and Jason Isbell. To hear some of the Americana artists talk about him, those comparisons seem unassailable. But that homage is not a not a full reckoning. It doesn’t capture all of him. For that, I needed to dig deeper into his catalogue. In that archeology, I rediscovered his 1996 album, “Mr. Happy Go Lucky,” his post-heart-attack record. I suspected that the truth about Mellencamp was somewhere in that overlooked, middle-aged bridge between life and death.

“Mr. Happy Go Lucky” was Mellencamp stripped of pretense, eager to slow down and ready for his second half — however long that might be. It’s an outlier in his catalogue — the least tethered to American roots music. It doesn’t sound like The Heartland and The American Dream is neither an explicit or implicit theme. It fared poorly on mainstream Rock charts and with previously sympathetic critics. For this record, Mellencamp curiously decided that what he wanted to say, after his near death experience, had to be said with the help of Junior Vazquez, a producer best known for Latin-inspired beats in the work by Madonna, Janet Jackson and MC Hammer. According to Mellencamp himself, “The idea was to take some of the Delta blues from the ‘30s and ‘40s and mix it with the beats from the ‘90s.”

The results bear little resemblance to their maker’s description. Instead, the album attempts to reclaim ground that Mellencamp had ceded to Counting Crows and then to the Gin Blossoms. It also completely presages the barely Alternative, barely exotic, Adult Contemporary music of Rob Thomas teaming up with Carlos Santana. And then, having set the blueprint for late Nineties Starbucks Rock, he adds congas for good measure. You would know none of this from the opener, “Overture,” which is a 2 minute string arrangement. For a brief moment it sounds like Mellencamp looked into the eyes of late 90s Billy Joel and liked what he saw. From there, however, Mellencamp finds his footing and his groove. It’s a hard groove to describe — part Eastern snakecharmer part, Margaritaville for the twenty first century.

Amazingly, he pulls much of this off admirably. The record “feels” good and sounds easy. Mellencamp’s rasp has a familiar ease about it. So much so that, on “Jerry” — the album’s second track — you want to shake your hips even though the jangle is darker than you might expect. Instead of a fiddle, there’s a Dobro guitar solo. For one song, it sounds like a Steve Earle record. You briefly imagine him standing on the heels of Whiskeytown and Wilco, jumping on a bandwagon that he unknowingly helped to start.

Unfortunately, that’s the last song of its kind. From there, everything gets lighter and more repetitive. There are conga drums everywhere. There are tape loops and breakdown beats. There are lots of exotic ingredients but never a solid meal. “Key West Intermezzo” is the big hit from this album. It was also the only hit, a minor hit and, specifically, an Adult Contemporary hit. It really feels like a Counting Crows song, performed by Hootie and the Blowfish with John Mellencamp on vocals. It goes down easy, as does much of this record. But it’s hard not to feel like you accepted an invitation to the Heartland and found yourself in at a Jimmy Buffett concert. It’s almost too obvious to say that this song, as with much of this album, is the perfect soundtrack to a forty something getaway at a five star hotel in Florida (not the Caribbean). In the Caribbean, they’d be playing actual Reggae or actual Latin music.

Throughout the record, the Eastern guitar stylings and minor chords signify that Mellencamp is serious. The congas — and they are everywhere — signify a lack of song. But somehow, while there are many musicians and even more instruments, nothing on the album is overstated. The experiments are seasonings, not the primary ingredients. But there is a lot of seasoning on “Mr. Happy Go Lucky.”

There’s something so simple and intuitive about Mellencamp’s basic formula — acoustic guitar, power chords, raspy voice, bass drum and gospel background singers. It almost always works, so you just expect for him to return to form. There are moments here, like on “Large World Turning” when you say to yourself, “here it comes.” You hear traces of “Lonely Old Town” or “Hurts So Good” but then the chorus falls flat and the hooks get too clever. In truth, most every song here has something interesting about it. For the first minute, they all have potential. They look good on the menu. But none of them taste right.

Towards the record’s end, we get “Jackamo Road,” which immediately sounds different. For one, it is just John Mellencamp and an acoustic guitar. Nothing else. It also really sounds like a young Bob Dylan for about ten seconds. It’s a sweet little ditty. Nothing fancy. No big chorus. But no mistakes either. About eighty seconds after it starts, it ends. Kind of. I remember thinking, “I want a whole album of that stuff. But as the song fades, something unfathomable happens. John Mellencamp decides to add a tuba solo to his perfect little coda. Can we agree that, unless you’re Randy Newman, or you’re joking around, that you’re not allowed to have a tuba solo in a Rock song? Can that be a rule?

Thirteen songs later, I conclude that “Mr. Happy Go Lucky” is not cloying or pretentious. It’s not a debacle or an embarrassment. It’s a forty five year old divorcee and heart attack survivor whose old formula wasn’t working for him anymore. Change made sense. It’s what the doctor ordered. But rather than quitting cigarettes or walking away, Mellencamp just downshifted into an alternative was rich and light in the same way that Matchbox 20 or Starbucks was rich, light and alternative in 1996.

This is not a No Depression album — it’s a well prepared venti latte with one pump of cinnamon dolce syrup and two pumps of pineapple ginger.