Mike Schmidt “Two Very Bad Knees and a Dream”

Pete Rose was filthy. His hair was designed that way either because he was incapable of combing it or because it made his helmet fit better. George Brett was gap-toothed and blonde. He had hemorrhoids and a temper. Willie Stargell had a gut. Dave Parker and Keith Hernandez smoked in the dugout. Rickey Henderson was from another planet. Half the league was popping pills. And the other half was coked out. The joy of Willie Mays was replaced by the swagger of Reggie Jackson. The 1970s were a decade of radical change and lost innocence for major league baseball. It was also a decade of multiple dynasties (A’s, Orioles, Reds and Yankees). The 1980s, meanwhile, were perhaps weirder still. It was neither a hitters era and nor a pitchers era. The Mets were briefly the greatest and grossest team on earth. What had been a relatively staid game from 1920 through most of the 1960s was suddenly less predictable. In fact, it was becoming downright bizarre. Change was everywhere. Except, of course, at third base in Philadelphia.

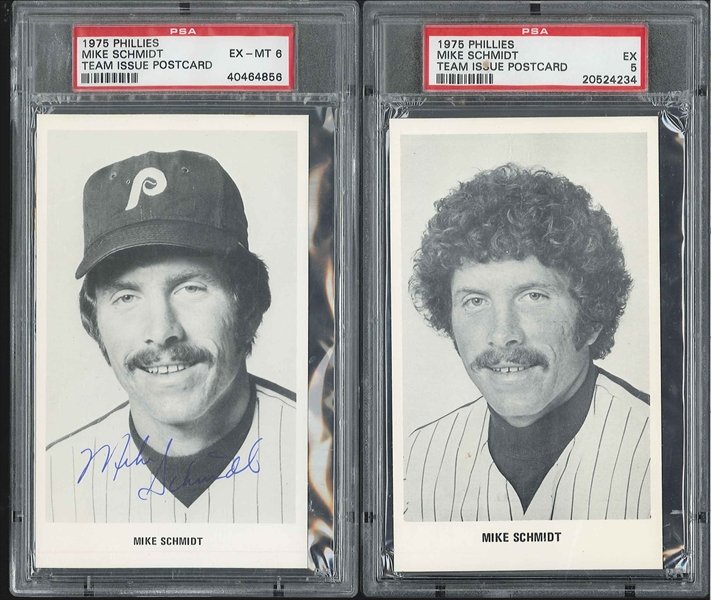

Mike Schmidt was the exact opposite of weird. He did not take drugs. He didn’t even spit. His uniform always seemed freshly pressed, bordering on preppy. Even when he was younger and his hair was thick and unruly, his mustache was immaculate. Eventually, he’d tame his hair with a perm and, when that didn’t suffice, with aerosol spray. His mighty swing was functionally the same for every one of the two thousand, four hundred and four games that he played with the same team. He chopped down towards the ball like a lumberjack striking a tree, rotating his hips perfectly and then following through the ball and back up and around towards his shoulders. It was a swing that produced only two results -- hard ground balls and searing home runs. At third base, he was practically robotic. Unlike Brooks Robinson, he rarely dove. His play didn’t look spectacular. But that was simply due to the speed of his reflexes and the ease of his range. Even when he’d move in on a slow roller, barehanding the ball and throwing it, sidearm, on target to first, Mike Schmidt made the most difficult plays look easy.

He did his job, better than anyone had ever done before him, with remarkable consistency, for the better part of eighteen years in the majors. He did it for terrible teams in the early 1970s. He did it when his more popular, less square, teammates resented him. He did it when Philly fans booed him. He just worked and worked, getting better to the point of being the absolute best. Along the way, he won eight home run crowns -- more than anyone not named “Babe Ruth.” He made twelve All-Star teams. Won ten gold gloves. Was a three time MVP. And he brought Philadelphia their first World Series title in 1980. He consistently hit forty home runs when that was rarefied air. And he averaged over a hundred walks per season. He was an advanced analytics dream. And he was a Philadelphia Inquirer reporter’s nightmare. No scandal. No gossip. No scoops. Not a lot of joking. Short responses. He wanted to be rich but not famous. And, most of all, he wanted to get back home to his wife and kids. And then back into the cage for more practice.

Schmidt’s perfectionism came at a price. He could endorse milk or American made automobiles, but he’d never be like MJ or Bo or Pete Rose or, even Lenny Dykstra for that matter. His brand was like Kenny Rogers, but more muscular and less horny. If “Schmidt” were an 1980s brand of cologne, it would smell like hard work, hairspray and baseball leather. And Ralph Lauren would mock it and absolutely nobody would buy it. It was a heavy burden -- to be that great and, also, that good. But Michael Jack (as he was often called -- as though he were the sweet, eight year old from down the block) was both of those things.

Iron Mike persevered through the lean years, through the years when he was the star but Pete Rose was the favorite, and through the increasingly terrible seasons after the Phillies’ 1983 World Series defeat. As he approached forty, he remained incredibly fit and productive. There was another, final MVP season in 1986 and a statistically similar season (without the awards) in 1987. On the surface, all we saw of Schmidt was red pinstripes and home runs on the field and fitted suits, pastel sweaters and glossed, auburn hair at the press conferences. But, underneath, the greatest Philly of all time was straining. A tear seemed inevitable.

The 1987 Phillies were a mediocre team that started out much worse than they ended up. At thirty-seven, Schmidt was six years older than the next oldest starter -- Lance Parrish (who, himself, seemed about forty at the time). The team had no pitching and was stuck in between a youth movement and a complete rebuild. As the early season losses began to mount, all of the team’s attention seemed to be focused on one thing only -- Mike Schmidt’s five hundredth home run. It came on April 18th, in a relatively meaningless game against the Pirates, wherein the Phillies had squandered a five run lead. But in the top of the ninth, with two men on, Schmidt chopped down and turned on a Don Robinson fastball, sending the ball soaring over the left field fence, for a game winning, three run homer.

While he’d hit four hundred and ninety-nine major league home runs previously, this one was very different. It was a milestone, yes. It was a game winner, yes. His entire family was in the stands and his teammates and fans erupted with excitement. There was drama, of course. But to see Schmidt’s response to the home run was to know instantly that this home run meant something else. Within a second of the ball hitting his bat, the slugger clapped his hands, pumped his fists and arms like a locomotive, and short-skipped with a giddiness that betrayed his famous professionalism. It was the reaction of a little leaguer winning his first world series. It was the reaction of a rookie hitting his first major league home run. It was the reaction of an All-Star redeeming his franchise. It was the reaction of an MVP who was never loved enough. It was both the redemption and breaking point of a perfectionist.

The Phillies finished the 1987 season two games under five hundred. The next season, Schmidt tore his rotator cuff, failed to hit twenty home runs and watched his team bottom out. He returned, seemingly healthy, in 1989. He appeared poised to chase Frank Robinson and, maybe even Willie Mays, on the all time home run list. He was Michael Jack Schmidt. For almost two decades, he put on that red and white uniform and hit long balls. But not in 1989. Or, only barely. While his team was on their way to another last place finish, their star struggled to hit two hundred. There were a few home runs left in the bat. But, sometime in 1987 after that five hundredth home run -- maybe that very day, maybe with that very crack of the bat -- something had changed. Maybe it was the release of tension. Maybe it was the ultimate validation. Maybe it was his wife secretly hoping that he’d quit chasing perfection. Maybe it was how his kids smiled at him. Who knows. Whatever the case, after the 1987 season, Mike Schmidt was never the same baseball player.

On May 29th, 1989, one day after going 0 for 3, in the midst of a 2 for 40 slump, on the heels of a five game losing streak, three weeks removed from his last home run and while on the road in California, Mike Schmidt announced his retirement from baseball. And though it made all the sense in the world, the shock was electric. ESPN fumbled their way through SportsCenter, waiting with bated breath for Schmidt to walk up to the podium that night in San Diego. Soon enough, Charlie Steiner cut away from the discussion of NBA playoffs and Kevin Mitchell’s ascending greatness for what would be among the most devastating four minutes of my young life.

As he walked towards the podium, you could sense the pall hanging over everything. Schmidt was dressed in a dark suit, with a white shirt, a high collar, a tie pin and a red pocket square. His hair was carefully blown and brushed dry and then sprayed with an extra dose of lacquer that night, in hopes that his outward appearance could contain the storm waves inside. When the reporters quieted and Schmidt did finally speak, you could immediately tell that the always steady third baseman was anything but. He cleared his throat and began by assuring the room that this was a genuinely happy moment for him and his family. He then inhaled deeply in between his well prepared “thank yous.” And then, finally, in a measured, if wobbly tone, he began what, to my knowledge, were the last two sentences of his retirement speech. He said, “Some eighteen years ago, I left Dayton, Ohio, with two very bad knees and a dream to become a major league baseball player; I thank God it came true." In between the first and second sentence he began to cry. At the end of the second sentence, he was bawling. He then walked away from the podium and I turned the TV off, barely able to breathe.

I was fourteen years old at the time and I’d never seen a grown man cry before.

It’s true. I’d never seen my father cry. No weepy grandpas or tearful uncles. Not one. At that point, my life had been blessedly free of sickness and death. To this day, I am unsure if the press conference continued after that point, because, to me, the story was no longer that Mike Schmidt had retired. It was that he’d cried. In the coming days, I read interviews wherein Schmidt, struggling to excel, unable to fathom how he could meet his own standards, much less those of twenty five year old Will Clark. The idea of being “very good,” or worse -- “pretty good,” or unthinkably -- “not very good” -- was clearly intolerable to Iron Mike.

Philadelphia sports fans are known for their lack of generosity. One of their least charitable nicknames was “Captain Cool,” a snarky, classist tag they affixed to Schmidt on account of his professionalism and introversion. It was not meant as a compliment but rather as a contrast to “Charlie Hustle.” It suggested “aloof” and “rich” rather than “esteemed” and “hip.” But on May 29, 1989, Schmidt was none of the above. He was an inordinately successful grown man. An elite athlete. A Hall of Famer. He’d hit five hundred and forty eight home runs. But, for his entire career, some part of him still seemed to be stuck in little league, striking out with the bases loaded. The night of his farewell, Schmidt got unstuck.

In the same way that his five hundredth home run dislodged something inside the slugger, his retirement completely, and immediately, released him. He moved to Florida where he played exceptional, near-professional level golf. He did occasional color analyst work for The Phillies. He talked to the press. He quit worrying about his legacy and coaching gigs and why Luzinski never liked him and why Reggie got more endorsement deals than he did. Eventually, he even shaved his mustache, let his hair go white and threw away the Aqua Net.

I’ve recently become enraptured by an English competition show called “The Great Pottery Throw Down,” wherein -- as the title suggests -- contestants compete by throwing, sculpting, designing and decorating clay. The show’s lovable host, Keith Brymer Jones -- the Mike Schmidt of wheel throwing -- is regularly brought to tears when he is in the presence of well made pottery. His weekly crying is a major part of the show’s appeal -- it’s sweet and funny and adorable. But it’s also confirmation of the changing definition of masculine competency. Today, when we see an athlete crying during the national anthem, it reads honest and courageous. Similarly, when Wayne Gretzky, Tiger Woods, Michael Jordan and Roger Federer weeped on screen, it humanized them, but it also affirmed a sense of greatness to us -- that their struggle to be perfect was impossible. And that they could admit that. And that it was OK. In fact, it was amazing. All of those crying GOATS walked in the footsteps of Schmitty.