Steve Garvey “Mr. Clean”

We really like our rags to riches stories. High schools all across the country have been staging versions of “Oliver Twist” since who knows when. Tales of Rockefellers, Vanderbilts and Carnegies confirm our national bootstrap-pulling. There is perhaps nothing more American than the story of a poor child who, through grit and ingenuity, goes on to make fortunes. I’m not sure how much of it we actually still believe, but it’s canon nevertheless. It fills encyclopedia pages. It’s still fodder for children’s books and PBS documentaries. And it’s history as much as it is fable.

But if we like our rags to riches stories, we love our riches to rags stories. “Schitt’s Creek.” “Trading Places.” That story of how Nic Cage bought an island, a dinosaur head, and not one, but two ancient castles. Or how Johnny Depp dropped five million to shoot Hunter S. Thompson’s ashes into orbit and how it costs him millions to have a private sound engineer feed him his lines on set. The barons of industry might fill up pages, but it’s the Cages and Depps that get the likes, emojis and dopamine hits rocking.

Steve Garvey wasn’t born in rags. He was no sharecropper’s son. Never slept on a dirt floor. His father, Joe, was a Greyhound busdriver who moved from New York to Florida, in part, so that he could drive the Dodgers around during Spring Training. It was through that assignment that young Steve got to meet Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider and the “Boys of Summer.” And, for six glorious springs, the Garvey served as Dodgers’ bat boy. So, a bunch of years later, when he was drafted with the thirteenth pick of the first round by the team he once picked up bats for, it seemed like more than just a validation of talent and hard work. It seemed like fate.

Between 1956 and 1966, The Dodgers appeared in five World Series championships. But in the seven years that followed, they never made it to the Fall Classic. Garvey arrived with the club in 1969 for a cup of coffee, and in earnest by 1971. By that time, Duke and Jackie and Sandy and Don were all gone. They’d been replaced with a crop of younger, promising but not legendary names like Sutton, Cey, Lopes, Buckner, Russell and, of course, Garvey. In 1974, the new gang had filled out and, over the next eight seasons, The Dodgers would return to the World Series four more times.

Those Dodgers were not like the old Dodgers. For one thing, they played in Los Angeles, which was absolutely not Brooklyn but where it was always early summer. They were also grittier than their more spectacular forebears. They won not through home runs and strikeouts but through all “the little things” — solid fielding, speed, hit and runs and control. They were a diverse and eclectic team, full of “very good” players — All Stars who might not have been All Stars had they been playing in Minnesota or Kansas City but who were famous because they played near Hollywood. Of all those players, only Don Sutton ever made it to the Hall of Fame. But a whole bunch of them would surely have plaques in the “Hall of Very Very Good.” The one outlier, thouhgh — the guy who was considered the surest of sure bets, as American as apple pie, as handsome as any movie star and as natural as Roy Hobbs — was Steve Garvey.

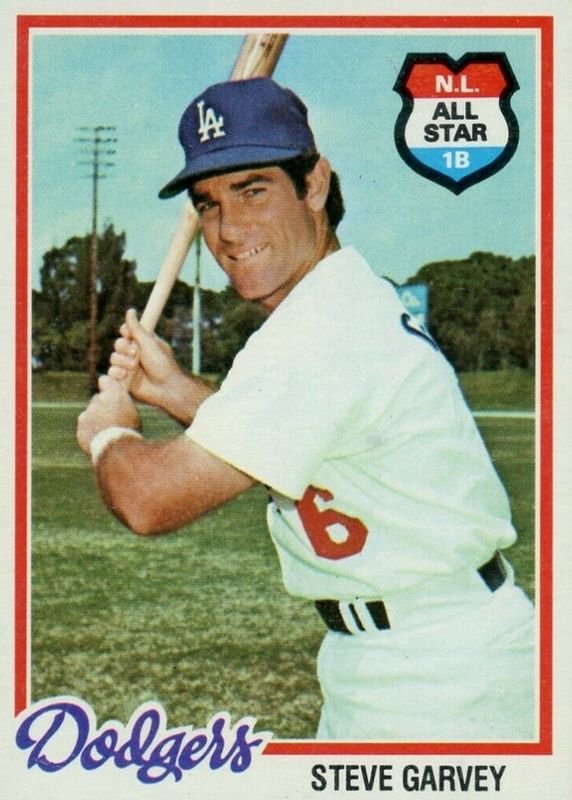

Garvey was the clean living (he didn’t drink, smoke or take drugs), god loving, good looking MVP at the heart of The Dodgers batting order. Early on, he’d been moved from third base to first because he’d hurt his arm years earlier playing (of course) quarterback. But, almost as soon as he made the move, he became a reliable Gold Glove at his position. Moreover, Garvey was the most dependable Dodgers’ hitter of the Seventies. Between 1973 and 1982, he averaged 194 hits, 21 home runs, 100 RBIs and a .305 average per 162 games. His streak of 1,207 consecutive games played is fourth most all time. He was the league’s MVP in 1974. For the better part of a decade, he was nearly everything that The Dodgers’ needed and was most certainly everything that baseball fans wanted.

But also, his appeal went far beyond his performance on the field. Garvey wasn’t just the reliable “Iron Man” or the white bread “Mr. Clean.” He was “Captain America.” Square jaw. Not a hair out of place. Biceps and forearms that resembled spinached-up Popeye. He was polite. And photogenic. He had the athletic, hirsute appeal of Jim Palmer but without the effete uppityness. And, what’s more, he was married to Barbie! Cynthia Truhan (formerly Garvey) was his beautiful, blonde partner — a staple of magazine photos and, eventually, Regis Philbin’s co-host on “A.M. Los Angeles.” Together, The Garveys were the picture of a pre-Reagan American ideal — slightly modern (She had a career! He was a famous athlete! They lived in LA!) but traditional in their values. They were late night talk show guests. Grist for People magazine. They were posters for “Morning in America,” contrasting with the increasingly diverse, increasingly hip, increasingly narcotic-curious dugouts of the major leagues.

For a few years the Garvey’s made their squeaky cleanness look natural — easy. But by the late Seventies, cracks were beginning to show in the armor of Captain and Missus America. It started with quiet rumblings from teammates about Garvey’s media-savvy — suggesting that it was both self-promoting and patronizing. In 1978, those rumbling became headlines when Don Sutton told a reporter that it was Reggie Smith, and not Steve Garvey, who was the team’s real MVP — the heart and soul of the clubhouse. Sutton’s comments allegedly went on to include an ungenerous something or other about Cynthia Garvey, which, in turn, led to actual bloodshed. Sutton and Garvey, neighbors in the locker room and in real life, wrestled and exchanged punches. Both men were scratched and bruised. Both claimed that they patched things up soon after. But very few people believed them.

Garvey used to write the number “200” in his glove at the beginning of each season as an inscription of his goal for the year — to collect two hundred hits. Amazingly, between 1974 and 1980, he achieved that goal six times in seven seasons. The year he missed — 1977 — he had “only” 192 hits but set career highs in home runs and RBIs. Garvey had an actual system for getting to 200. It involved getting on base through bunt singles and opposite field hit-and-runs a certain amount of times. It involved not striking out, but also, not walking. And, finally, it involved showing up and playing every single game. To fans, that workmanlike attention to detail was inspiring. To others, it reeked of “me first” stat compilation — of somebody obsessed with personal glory and achievement. Like somebody who would game the system to make himself look better.

In 1981, after having lost the World Series to the A’s in ‘74 and the Yanks in ‘77 and ‘78, The Dodgers finally got over the hump. It was a strike shortened season and a good but not great one for Garvey. While the fireworks were going off in Chavez Ravine, however, the real explosives were being detonated back at home inside the Garveys’ marriage. Rumors of Steve and Cyndy’s marital troubles had persisted for years. Rumors teammates didn’t like her. Rumors that teammates’ wives really didn’t like her. Even rumors that Steve resented her desperate celebrity and that she could not stand his cloying morality. The couple divorced in 1983, but the acrimony remained intense — and intensely public — for years to come.

1982 was Garvey’s last year as a Dodger. Though he was still a star, he was no longer an All-Star. And so, in 1983, he signed as a free agent with the Padres, where he had four good, but not very good seasons, and one injury-plagued finale. In 1984, he helped The Padres win their first pennant, winning NLCS MVP and helping his club come back from two games to none. Garvey retired at the end of the 1987 season, gracefully, if somewhat reluctantly, and turned his attention to a second career in marketing. He’d established Garvey Media Group many years earlier, as a vehicle to monetize his image and consult with other media-conscious athletes. It was a move that would have made perfect sense in the late Seventies, when Garvey was a darling. By the late Eighties, however, it was Garvey and his image that gravely required counsel.

Though his divorce stumbled between bitter and grotesque, it almost paled in comparison to what would follow just a few years later. Between 1988 and 1990, Garvey was “outed” as having three girlfriends simultaneously, two of whom he proposed to and two of whom he impregnated. Around the same time, Cyndy released her autobiography, “The Secret Life of Cyndy Garvey,” which, among other things, painted her ex as aloof, duplicitous and vain. She claimed that he was emotionally and sexually withholding. That he was an absentee father who stuffed All Star ballot boxes. It was catnip for the press. And, amazingly, it was still only the beginning.

After the romantic humiliations came the financial ones. Garvey owed money to his ex-wife. And to the other women whose children he’d fathered. Garvey sued Cyndy for more custody of their daughters, who were either tragically, deliberately estranged or unusually good at avoiding their dad. Legal fees mounted. There were reports that he spent $2,700 at a charity auction for his church and then never paid the bill. Meanwhile, Garvey Media never took off (probably not great business for the “media expert” to be a “media disaster”). Amid all of this, Garvey and his second wife, Candace, were living in a five million dollar mansion in Utah, employing a team of assistants who they could not reasonably afford and who, in fact, they occasionally stiffed.

Way back in 1980, at the age of thirty-one, Garvey had his sixth and final 200 hit season and placed sixth in the NL MVP voting. He was on his way to a 3,000 hit, 1,500 RBI, Cooperstown worthy career. He retired well short of those numbers but still with the kind of statistics that eventually get you into The Hall. In 1988, the year after he retired, he was considered a strong to excellent candidate. And in 1993, his first year on the ballot, he received nearly 42% of the vote share — far less than the 75% required for enshrinement but consistent with many candidates who do eventually get elected. Traditionally, if a player is a strong candidate, their vote shares will gradually creep up after their first year on the ballot. But Garvey’s plateaued and then retreated. He lacked the writer’s votes and never got a serious sniff from the Veteran’s (Era) Committee, which consists entirely of former players.

The case against Garvey rests primarily on his hit-hunting, which depressed his walk rate, and therefore his on base percentage and therefore his WAR. Advanced statisticians are largely unimpressed with Garvey’s career. They view him as a fine enough All Star, but not an elite player. His defenders, of which there are still many, point simply to the “counting stats,” the awards and the simple fact that he was the best player on a great team for nearly a decade. The only other players with ten All Star appearances, four Gold Gloves, five top ten MVP finishes and one MVP award not in the Hall of Fame are out solely due to suspicions (or proof) of performance enhancement.

Garvey’s case is ultimately not black and white. It’s also most assuredly not a matter of statistics. The reason why he failed to garner support is much simpler than WAR or OBP or OPS+ — it’s because he was not well liked. Players resented his squeaky clean vanity. Writers begrudged his duplicity. Unpopular people rarely win elections. I suspect that Steve Garvey knows this. He was — and still claims to be — a media professional. And, astoundingly, his approach to the media has not changed over the years. Not one iota. He still blow dries, parts and combs his hair. He still starches his shirts. He is still polite in his manner, religious in his faith and conservative in his politics. He does not deny many of the claims against him. He acknowledged his “mid-life disaster.” He is well aware of his financial woes. But still — even now in his Seventies, even after all of the debacles — Steve Garvey talks about running for Senate. Not too long ago, and in spite of his insufficient net worth, he made a strident case for buying the Los Angeles Dodgers. Because the thing about Captain America is less that he is infallible and more that he believes that he’s the hero. And the thing about The Iron Man is less that he is infallible and more that he consistently shows up. And the thing about Mr. Clean is less that he is spotless and more that he is capable of removing the stains.

I’m quite sure that Steve Garvey was a great baseball player. Similarly, I’m certain that if in 1973 somebody had explained to him this future thing called “W.A.R.” he’d have adapted and walked hundreds more times. I’m much less certain of his character — he sure seems deluded, if not, craven. And priggish, if not holier than thou. But those are not Hall-disqualifying flaws. In the end, he was never Rockefeller rich or Reagan popular, in the same way that he was never an impoverished orphan. But he lost so much of what he once gained. Which is why Garvey’s story is a fundamentally modern American story. We had “Oliver” and “Annie.” Our grandkids will have “Steve” and “Cyndy.”