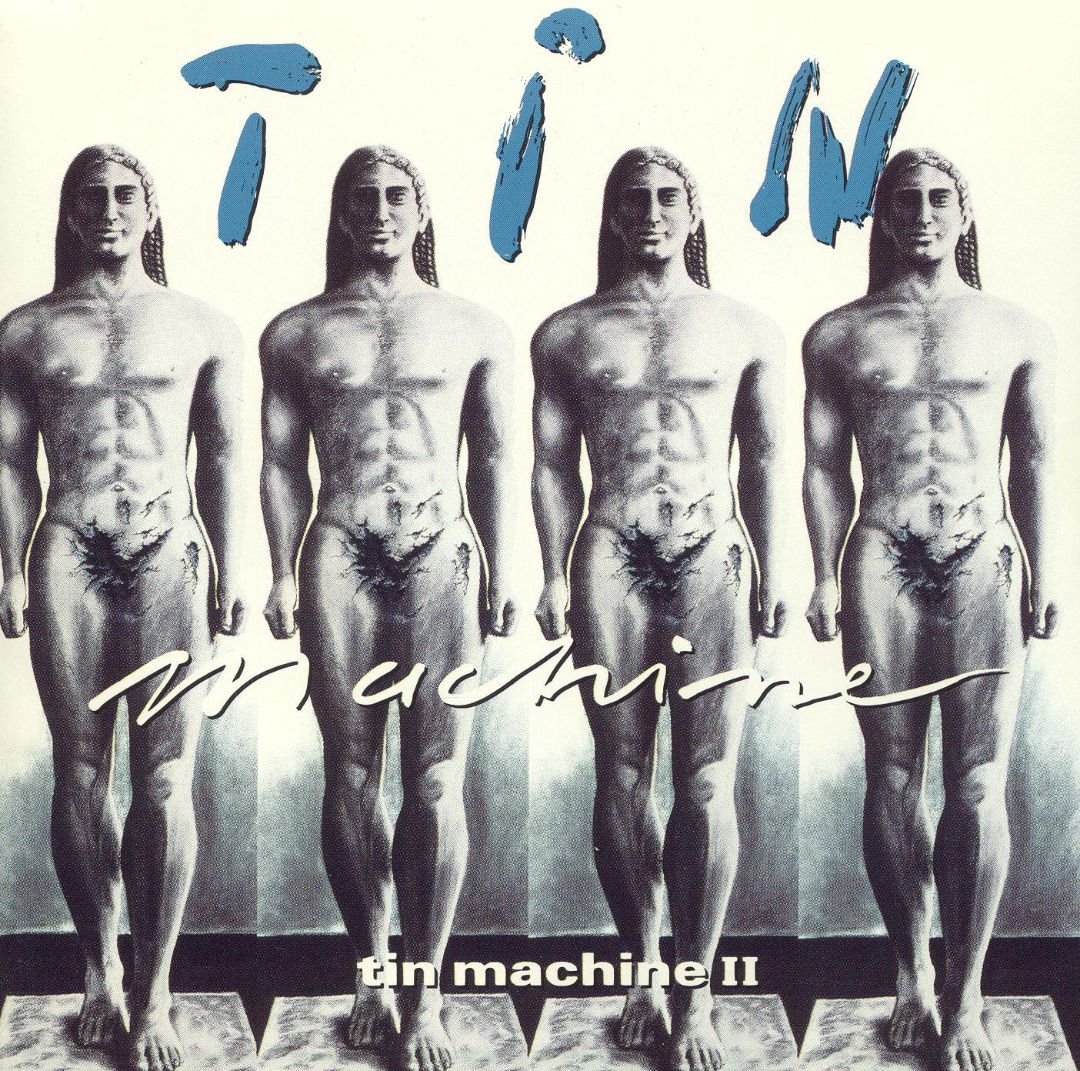

Tin Machine “Tin Machine II”

The generous assessment of David Bowie is also, undoubtedly, the most popular one: Bowie the trailblazing icon. The risk taking genius. The glamorous gender bender. The innovative shapeshifter. The maker and breaker of genres. The producer of stone cold classics — from Ziggy through the Berlin Trilogy and New Wave — right up until the day he died.

In this telling, “innovator” and “chameleon” are basically synonymous. And, it goes without saying, both are pejoratively positive. Bowie’s “innovations” were marked by their chameleonic qualities — by his capacity to see and hear something just beneath the zeitgeist and to adapt alongside it. It was not so much that Bowie was disrupting culture as he was metabolizing and evolving based on something in the milieu. He didn’t invent Glam so much as he assimilated it. Same with Krautrock. And Punk. And New Wave. And Industrial. And Jazz. In this way, he was as much a parasite as he was a chameleon. Chameleons respond to their environment whereas parasites feed off living hosts (which also happen to be their environment). This is the second, less popular, but still widely held assessment of David Bowie: Bowie the extraordinary parasite.

There’s another term for brilliant, charismatic parasites who take on a human form and feed off of others. And that, of course, is “vampire.” Bowie was more than a little “vampire curious.” He played one in “The Hunger,” a 1983 film directed by Tony Scott. And while the Thin White Duke was Bowie’s most vampiric character, even when offstage and make-up free, the former David Jones was a more convincing bloodsucker than Peter Murphy, Lux Interior or Marilyn Manson ever were.

Over the years, Bowie has been accused of feeding off of Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, Mick Ronson, Marc Bolan, Tony Visconti, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, Niles Rodgers, Trent Reznor and many more. In the 1970s, Bowie went through a coterie of hosts. Back then, the blood was fresh and the feeding was good. But, as is often the case in vampire stories, the bloodlust got harder and harder to sate. The thirst got thirstier. The feeding got frenzied.

During the Seventies, Bowie never suffered from thirst or hunger. But then, around the mid-80s, something changed. His hosts had grown older. The young blood was not so plentiful. After the unexpected success of “Let’s Dance,” inspiration began to run dry. He and Angie divorced in 1982. What was once underground and fresh — Punk, Electronic and New Wave — was suddenly Pop. Lacking inspiration, his vitality waned. “Tonight” from 1984 was a dud. The next year, completely depleted, he wiggled his hips and waved his fingers alongside Mick Jagger in a silly, if beloved, cover of a Motown classic. Two years later, on “Never Let Me Down,” he hit rock bottom. Critics sneered. Fans moved on. And, for the first time in nearly twenty years, David Bowie was not vital. He was the unthinkable: boring.

The mid and late Eighties were dark, arid times for Rock and Roll. There was no fresh blood for Bowie to suck. The top Mainstream Rock radio songs that year included Henry Lee Summer’s “I Wish I Had a Girl” (what? who?), Bruce Hornsby and the Range’s “Valley Road” (rocks so light) and Tommy Conwell & The Young Rumblers’ “I’m Not Your Man” (not a typo, I checked). Hair Metal was ascendant. U2 was in a period of awkward transition (“Rattle and Hum”) and REM was just beginning to cross over. If Bowie was looking for inspiration, the pickings were slim.

Desperate for anyone, anything new — Bowie did what desperate people do. He found the nearest available guy and went all in. No research. No waiting. No courtship. It almost didn’t matter who the guy was. He didn’t need to be a trailblazer or a prodigy. He didn’t need fame. Or indie cache. He just needed to have a beating heart, pumping blood and some capacity to make music. But mostly, he needed to be a willing host.

Reeves Gabrels was that new host. And, in spite of his regal sounding name, he was truly just a guy. A guy from Staten Island, New York, who happened to be married to David Bowie’s tour publicist. He’d never played in a famous band or a semi-famous band. He was not a renowned session musician. He appeared average in almost every way — medium height and build. Balding. He played a headless electric guitar, which signified Fripp-ian virtuosity rather than youthful spark. But, in almost every other way, he seemed like “just a guy” when Bowie needed “just a guy.”

Today, Reeves Gabrels is more of a known quantity. He’s considered an eminently capable and inventive guitarist. He spent nearly a decade as Bowie’s bandmate and has been the lead guitarist for The Cure since 2012. But, back then, in 1988, he seemed like the least likely, most convenient collaborator Bowie had ever picked up. One day, Gabrels was playing steel guitar in Rhode Island for a band called Rubber Rodeo. A year later, he was the cofounder of Tin Machine.

Tin Machine was David Bowie, Reeves Gabrels, Tony Fox Sales and Hunt Sales. The Sales brothers, who met Bowie while playing on Iggy Pop’s “Lust For Life,” were the children of comedian (and jazz aficionado), Soupy Sales. Tony played the straight man — sharply dressed, strong jaw and a big bright smile. Hunt, meanwhile, looked like trouble. While the rest of Tin Machine was carefully styled in double breasted suits and colorful dress shirts, Hunt played drums (and ran around) in his underwear.

In spite of their temperamental differences and their widely varying statuses, however, Tin Machine presented themselves as a band of equals. From the outset, they were adamant that David Bowie, one of the most famous musicians on the planet, was absolutely not the leader of the band. There was no spokesman. Songs could and would be written by any one of the guys. They dressed as a band. They did interviews as a band. Tin Machine made it very clear: They were not “David Bowie and band.”

Prior to their debut, Tin Machine was somewhere between hypothetical and theoretical. The hypothesis, I think, was that David Bowie could thrive in the context of an egalitarian band. That, following two terrible solo albums, a band was precisely what David Bowie needed. In theory, it made sense. But, in reality, no one was buying it. Not a soul. It sounded like a gimmick. Like another character for David Bowie to play — guy in a band. Everyone assumed (and hoped) that it was just a ploy — that Tin Machine would ultimately be revealed as a pseudonym for “The David Bowie Band” and that the ruse would play itself out and that, in a year or so, David Bowie would return to being David Bowie.

Until then, everyone had to play along. The schtick about Tin Machine was supposed to be that there was no schtick. They were simply an Alternative Hard Rock band, in the days after The Pixies appeared but before Nirvana made that idea a popular concern. They dressed like wealthy, middle-aged men. More specifically, they dressed in clothes that looked like Giorgio Armani and Tommy Bahama had a baby. Or like if somebody took Chandler Bing’s work attire and added massive shoulder pads and glow in the dark shirts. It was a ridiculous uniform, the sort of thing that no forty-something man could reasonably pull off. Unless, I suppose, the man was David Bowie.

Aside from their stylized uniforms and their headless guitars, though, Tin Machine proved true to their words. Mostly. They made loud, anxious, off kilter Rock music. They did interviews as a band. Most of their songs were written either collaboratively by Bowie and Gabrels, or as a band or as some permutation in between. Bowie handled all of the lead vocals on their debut, but, live they presented like a band — Bowie stepping back to marvel at his guitarists’ handiwork while the mostly naked drummer pounded away in the show behind the show.

While they were interesting to look at and to consider, Tin Machine were simply not a great band. Or rather, they were an underdeveloped band with underdeveloped material. Whereas Bowie’s best work sounds studied — meticulous — Tin Machine was (intentionally) more spontaneous. And that combination of an exacting, cerebral frontman singer on top of squealing, angular din proved to be unappetizing. In 1989 there was no name for Rock music with poetic lyrics, unstable tempos and muscular guitars. But soon after, it got a name: Grunge. Tin Machine was like untested, overcooked Grunge.

But, before that was apparent — before the one star reviews came in and before people started calling them “Shit Machine” — Bowie devotees and curious onlookers briefly tuned in. And then, in May of 1989, “Tin Machine” emerged. There was an initial flurry of activity. The first single, “Under the God,” forced its way onto the Mainstream Rock radio charts. Early sales were brisk, if not outstanding. And, for about two hours, the time it took to purchase and consume the record, critics gave the band a wide berth, only to quickly close ranks.

In a matter of weeks, the ground shifted. Tin Machine was no longer a hypothetical. They were a real band with a real album and a bunch of modest tour dates planned. Their music was both odd and oddly underwhelming. And though he was the singer and the most prolific songwriter and a global superstar, David Bowie refused to act like David Bowie. A whole lot of people who waited for Tin Machine, were expecting David Bowie. Those people were disappointed. Devotees were not devoted. Critics were critical. Everyone in between was confused. And then, in a matter of months, it seemed like it might all be over.

In the spring of 1990, when Bowie embarked on the Sound+Vision Tour — a live greatest hits package coinciding with the release of his retrospective box set — it absolutely seemed like Tin Machine was finished. For that tour, Gabrels was replaced by Adrien Belew. The Sales brothers were nowhere to be seen, and it was Bowie back to playing the classics — “Changes,” “Heroes” and the like. From the outside, it seemed that the jig was up. While novel in theory, Tin Machine was an invalid hypothesis.

And yet, when asked about Tin Machine during interviews, Bowie was insistent that he planned to return to the band as soon as his tour ended. Nobody believed him. Why would they? Why would he soldier on in Shit Machine when he could cruise through an endless series of victory laps for the rest of his career? The most obvious answers were loyalty and necessity. Bowie both appreciated Gabrels and, more importantly, needed him. Bowie could still act the star. He could still sing the hits. But his well was still dry. He still needed a host to feed from. And Gabrels was still that guy.

If “Tin Machine” provoked minor curiosity and major disappointment, its sequel inspired very little of either. “Tin Machine II” came and went in the late summer of 1991. It was supported by a number of high profile TV appearances and an extensive tour. But, other than the chance to see David Bowie live, nobody seemed to care. It was a dud on arrival. Reviews landed somewhere between tepid and angry. Thirty years later, the album is not even available on streaming services. In fact, until about a month ago, though I’d heard every single album that David Bowie ever released, I’d never once heard “Tin Machine II.”

In death, there’s a natural tendency to revisit and rewrite the past with the bias of sentimentality. There’s a similar, and probably related, urge to dig up something old and obscure and extol it as critically important or valuable. But Tin Machine were not The Velvet Underground or The Stooges or Television. And “Tin Machine II” is not some misunderstood, under-appreciated gem. It’s not the great, forgotten uncle of Grunge. It’s not the misunderstood cousin of The Pixies. I’ve searched for some corner of the internet wherein “Tin Machine II” has been reclaimed by fans or academics. No dice. Aside from the occasional “Baby Universal is pretty good” and half-hearted “it’s better than I remembered,” people seem comfortable forgetting that it ever happened.

But it did happen. On September 2, 1991, Tin Machine released their second album, which included material from their first recording sessions as well as a bunch of new stuff made with the benefit of hindsight. According to reports, the second time around was less of an egalitarian affair. David Bowie was the boss — why pretend otherwise? He wrote most of the songs. He sang most of the leads. And, aside from the two times that he handed the mic to Hunt Sales (who was, at the time, in throes of drug addiction), he was the main attraction. As the official shot caller, Bowie added more melody, structure and R&B influences where before there was aimless, shapeless noise.

And for three minutes and eighteen seconds, it almost worked. “Baby Universal,” the first track and second single from “Tin Machine II,” is massive in the way late period U2 singles could be. Huge power chords over a bottom that races towards terminal velocity. Unlike Bono, though, who sounds irrationally confident, Bowie’s excitement is of the nervous variety. The chorus doesn’t completely pay off, but the pre-chorus (Failures as fathers/Mothers to chaos) is as good as past prime, apocalyptic Bowie ever got. It’s not simply the best Tin Machine song (that’s not much to boast about), it’s a genuinely excellent David Bowie song.

From there, however, it’s all downhill. At first, the descent is not so steep. “One Shot” is generic, arena Alt Rock before that term applied. “You Belong in Rock and Roll” is going for a slightly gothic, crooner vibe — like Echo and the Bunnymen via Roxy Music. Aside from Bowie, who pairs his hushed baritone with his arty saxophone, though, the band plays things pretty straight. And it almost gets there — to that place between who The Cure once were and who Nine Inch Nails would one day become. But it doesn’t. Because, like almost everything Tin Machine ever made, it’s a profoundly interesting frontman, playing alongside a mostly interesting band, playing a bunch of largely uninteresting songs.

Time. And material. Tin Machine lacked both. There’s probably another world wherein — given years to write together (or let Bowie write for them) and figure out their respective strengths, Tin Machine could have been something extraordinary. There are moments, like on “A Big Hurt,” where you hear the band reaching for The Pixies. Getting closer. There’s a delirious squeal to the guitars. The bass sounds like it’s having fun. The drums keep pace rather than weigh down. And Bowie sounds rejuvenated. But, also, it sounds like an imitation. And it would not rank among the fifty best Pixies songs. It’s a good idea, rushed out by a band still figuring things out.

Without enough songs in their songbook, and without enough time to polish the rock into stone, Tin Machine ultimately resorted to glorified tone poems about Indonesian regencies (“Amlapura”), enthusiastic but forgettable covers (Roxy Music’s “If There Is Something”) and — heaven help us — two Hunt Sales originals.

I almost hesitate to mention “Stateside,” which Sales sings on but which he co-wrote with Bowie, and “Sorry,” which is entirely Sales’ doing. To assail those two tracks feels like a cheap shot. Hunt Sales is obviously not the songwriter that Bowie was. And, according to most information on the subject, he was in the throes of terrible drug addiction during his tenure with Tin Machine, and, in particular during the end of their run. Of the very few people who’ve actually listened to this album and written about it, most take a swing at the Sales’ songs. I guess I will too. But not so much because the songs are terrible, but because the alternative would be disingenuous. “Stateside” is a competent, tedious Blues rocker that could have been something if Bowie sang lead. And “Sorry” is exactly what it promises — a three and half minute, lightly metallic ballad, sung on bended knees from a man who’s evidently apologetic, but who also should be nowhere near a microphone, much less a recording studio.

It would be convenient to blame “Tin Machine II” on Hunt Sales. There are times when it sounds like he only has one drum in his kit — the bass drum. There are other times when it sounds like he snuck into the mixing room late at night and dialed up his parts to eleven and the rest of the band’s down to seven. Yes — there is simply way too much Hunt Sales on the final Tin Machine album. But, alas, Tin Machine was a band of equals. They swore it up and down. They were four men. Two brothers — one with pearly white teeth and an expensive haircut and one who was constantly sweating his way through his underwear, which was also his outerwear. The lead guitarist wore shaded spectacles onstage and played a headless guitar and served as the host for the singer, who also played a headless guitar and who looked like a vampire supermodel and who also happened to be Ziggy Stardust.

In retrospect, there is something charming about four middle-aged men daring, trying to be different. Tin Machine certainly didn’t suffer from lack of charm or talent or ideas. They suffered from too much of those things and not enough of everything else. After a six month world tour that spawned a live album (“Tin Machine Live: Oy Vey, Baby”), Bowie continued to suggest that the band would return and make a third album. But, it never came to be. Hunt Sales was too sick — too unreliable. More importantly, in 1990 the former Thin White Duke met his future Duchess. Iman and David would marry in 1993, the year she officially became his new host and the year he released “Black Tie White Noise,” his first solo album since “Never Let Me Down.”