Wade Boggs “The Visible Man”

Wade Boggs could will himself invisible. As he recalls events, once — after leaving a dodgy Gainesville, Florida nightclub — a group of men attacked him at knifepoint. Surrounded, he used the only viable option to escape terrible injury: defying physics, he rendered each of his cells translucent and fled. Boggs knew that was an option because — believe it or not — that was not the first time Boggs had used invisibility to evade disaster. At the age of twelve, he protected his prized jacks from a group of malevolent football players by praying for the power to become imperceptible. It worked then, too.

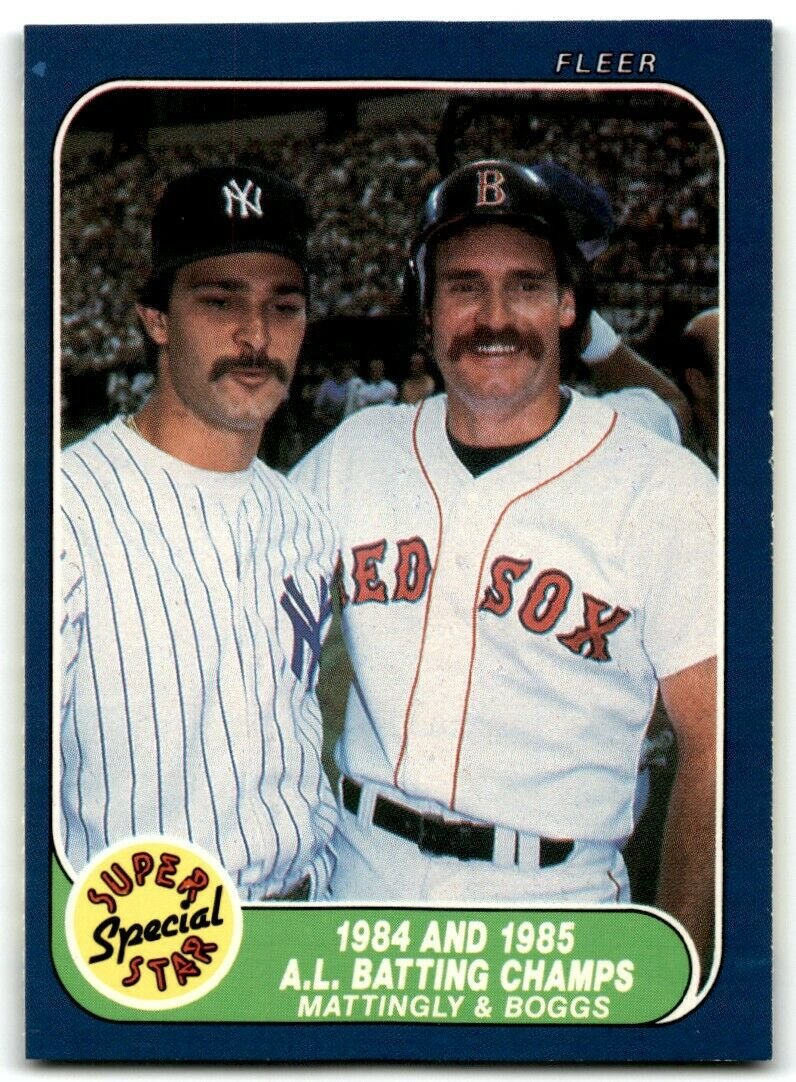

Many years after his initial discovery, while fully corporeal, Wade Boggs also willed himself to become one of the great pure hitters in the history of baseball. And although he was never named the MVP for any individual season, Boggs enthusiasts make a very strong argument that he was the best hitter of the 1980s. For the seven plus years that he played in that decade, Boggs batted .352 and was on base nearly 44% of the time. From 1985 to 1989, he had a WAR of over eight in every season. For context, that’s Mike Trout level high. Mike Schmidt never had five years of 8+ WAR. Neither did George Brett. His career WAR is higher than Ken Griffey Jr’s and miles past Pete Rose, Reggie Jackson and Derek Jeter. By almost any measure, Boggs was as unusual an athlete as he was a man.

Few scouts thought that Boggs would amount to all that much when leaving his Tampa-area high school Boggs remembered, “I was told in the minor leagues that I’ll never play third in the big leagues. That I don’t hit for power…I’m not fast enough. I was told so many different things.” But in the same way he didn’t allow physics to tell him he couldn’t disappear at will, he refused to be told that he couldn’t become a top-flight third baseman. “The only thing I ever wanted to do was play professional baseball.” And so, he did. For eighteen years, making twelve All-Star teams and retiring with over three thousand hits and and a career average of .328.

Boggs’s mind — while undoubtedly the source of all sorts of superpowers, including the ability to hit baseballs to the opposite field — was highly complex. Sportswriters labeled his legion of ticks and quirks as “superstitions.” He was generously entitled to this euphemism because he could achieve a .900+ OPS without hitting home runs and because he made millions and millions of dollars. If he were, for instance, a salesman at Kinkos or a Tampa area gym teacher, it seems fair to say that he would be considered profoundly and perhaps cripplingly neurotic.

The stories of Wade Boggs’s ritualistic compulsions are the stuff of legends: He could only eat chicken before baseball games. He took precisely the same route from the dugout to his position at third base. Before each at bat, Wade Boggs traced the Hebrew letter Chai into the dirt (Boggs is not Jewish.). He woke up the same time every day. He ran sprints every day at 7:17 pm. Whenever possible, he ended all activities on a “7.” His batting practice routing included searching for pennies near the Green Monster. He begged the Fenway Park announcer not to mention his uniform number because that gave him good luck. Wade Boggs was a strange amalgam of Ted Williams and Bob Wiley from What About Bob?

Through this Rube Goldberg machine of will and ritual, Boggs brought the Boston Red Sox one out away from breaking their curse and winning the 1986 World Series. He was the young, mustached face of the franchise and there was every reason to believe he would beat down the same path at Fenway until his retirement. According to Boggs, that was the verbal agreement he’d made with former Red Sox owner Jean Yawkey. In 1992, however, Mrs. Yawkey died and Mr. Boggs failed to hit .300. In the aftermath, the Red Sox presented Boggs with a lowball contractual offer, leaving their All-Star despondent.

So, in an act of profound (and perhaps petulant) transformation, Boggs tested the limits of will — perhaps beyond human invisibility — by shapeshifting from a Boston Red Sox into a New York Yankee. In a world before Roger Clemens and Johnny Damon and Jacoby Ellsbury, this was a shocking act of inverting the physics of baseball. It was, frankly, destabilizing to fans of both teams in an era where franchise icons like Boggs (or Brett or Schmidt or Gwynn or Ripken) would often remain with the same team throughout their career. Boggs was once again trying to render himself invisible: Yankee fans — you did not see me torment you for a decade.

But I had seen Boggs — many, many times. We had all seen him. He couldn’t make himself disappear. No amount of will could shake the intrinsic disorientation. As a young North Jersey teenager — and a Yankee fan by birth — learning that Wade Boggs was now on the Yankees was the equivalent of waking up and being told that New Jersey was suddenly part of Belgium. Beyond confusing, it made the arbitrariness of allegiances seem plainly silly. Perhaps I would have reached that conclusion as I reviewed childhood attachments through adult eyes, but Boggs certainly sped the process up. Maybe Wade Boggs could will himself into a Yankee, but I couldn’t will myself into the image making sense.

But then, in 1996, the Yankees — with Boggs at third base — won their first World Series in eighteen years. In perhaps the most famous image of the post-game celebration, Wade Boggs — despite his profound fear of horses — mounted a New York City police horse and — arms hugging the officer in front tightly — paraded around Yankee Stadium in triumph. I suppose he deserved the celebration as much as anyone else on the field. He had been an All Star. He had batted .311. But him celebrating along with Derek Jeter and Tino Martinez (and Don Mattingly, who’d just recently retired) required accepting the story that Boggs was telling: “Look at me, I am on a horse and love it! And I’m definitely not committing an act of historic disloyalty!”

As his prime receded into the twilight of career, Boggs joined his hometown (and newly created) Tampa Bay Devil Rays. These last two years were relatively unremarkable aside from forty-one year old Boggs hitting a home run to reach three thousand hits and for his uncanny ability to scratch out a .301 batting average in his final season. Indeed, what makes these years notable at all, is the persistent rumor that the Devil Rays and Boggs agreed that — for a million-dollar bonus — he would enter Cooperstown wearing a purple Devil Rays hat (that final act of will never came to pass as the Hall of Fame cut Boggs off at the pass, changing their prior policy that allowed players to choose their team allegiance and hanging a plaque of Boggs wearing a Red Sox hat).

Wade Boggs told the world many stories. That he saved his own life by turning invisible. That he once drank 107 beers on a cross-country flight. That his baseball hitting prowess was aided by poultry consumption. That his ability to put a ball in play would be compromised by wearing the wrong pair of underwear. That he was a Yankee. Perhaps he wanted to tell history that his greatest contributions to baseball came in his hometown of Tampa Bay. Is Wade Boggs magical? Is he delusional? Is he just a neurotic with astounding hand-eye coordination and twitch muscles?

While those answers are either obvious or unknowable, one thing is certain: it must have been hard work to will oneself into becoming Wade Boggs. The highest compliment given to our athletic heroes are that they are “naturals.” Willie Mays or Joe DiMaggio or Mickey Mantle made it look easy. Wade Boggs had to hit 100 mph fastballs and check his watch to see if he could end practice on a 7 and trace Hebrew good luck charms in the dirt and find missing pennies. While others could celebrate, Boggs had to ride on a giant, scary police horse.

As a kid, I hated Boggs because he was a Red Sox masquerading as a Yankee. As an adult, however, he seems far more sympathetic and far more understandable. To some degree and in some settings, we are all Wade Boggs — carrying our burdens, hoping that friendly people label them benign and that, when we are in true danger and we are truly vulnerable, just praying and praying that we aren’t visible.

by Kevin Blake