Art Garfunkel “Scissors Cut”

Once upon a time, Art Garfunkel could have been anything. He could have been a canter, draped in all white, bringing the synagogue to tears with his renditions of “Adon Olam” and “The Mourners Kaddish.” He could have been a mid-tier tennis pro — a follicular precursor to John McEnroe. He would have made a convincing pantomime or clown — physically, Artie was a more beautiful, less hysterical version of (Three Stooges) Larry Fine. Honestly, the possibilities were endless. He could have been a poet (which he eventually became) or an architect (which he once set out to become) or a professor of mathematics (which he dabbled in). But instead, Art Garfunkel ended up being “Art Garfunkel” — one half of the most famous musical duo from the second half of the twentieth century.

One half might even be generous. History suggests, as most people assumed, that Garfunkel was actually less than half of Simon and Garfunkel. And everything that Paul Simon accomplished after 1970 has only served to confirm that suggestion. But while it's almost indisputably true — Garfunkel was not the artist that his bandmate was — he was also, obviously, so much more.

Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel were born just a month apart. They met in grade school in Forest Hills, Queens and, by the time they were fifteen, they’d scored a minor Pop hit as “Tom & Jerry.” Both boys were sensitive and bookish. Simon was the short one with dark hair, who wrote the songs. Garfunkel was only 5’9”, but towered over his partner. He had a wide, pretty face with high, strong cheekbones. He couldn’t write music or play an instrument, but he could out-sing all of the choir boys in Queens.

If Simon was a prodigy, Garfunkel was not far behind. Between 1964 and 1967, during the years that Simon & Garfunkel released “Wednesday Morning, 3AM,” “Sounds of Silence” and “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme,” Art Garfunkel attended Columbia University, where he completed his B.A. in History and his Masters in Mathematics Education while competing in tennis, fencing, skiing and bowling. As if to humble his preternatural talent, fate twice cursed Art Garfunkel. First, he was given an uncombable shock of curly hair. Second, he was destined to form a band with the one man in all of New York City who was as bright, as sensitive and as exacting as he.

The story of Simon and Garfunkel, from Tom & Jerry to “Sounds of Silence” to “Mrs. Robinson” to “The Boxer,” is Boomer canon. They signified the exceptionalism of the children of Jewish immigrants. They were beloved all across America, but nowhere more so than their home, New York City. They also have the rare distinction of breaking up while at their absolute peak. Regardless of Boomer nostalgia, though, their swan song — “Bridge Over Troubled Water” — has endured as a masterclass in melody and song craft. It portended the direction of Simon’s decorated solo career and it contains at least four, timeless classics, including, of course, its elegiac title track. There have been more virtuosic vocal performances in the “Rock era” — Aretha and Whitney could be flawless. And there have been more impactful ones — Otis Redding and Al Green come to mind. But I do not know if there has ever been a more naked or beautiful vocal than Art Garfunkel’s on “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” It is a perfect song, rendered with a grace that soars into that very narrow sliver of sky between “transcendental” and “too much.”

If he’d never sang another song, Art Garfunkel’s performance on “Bridge Over Troubled Water” would have been quite a legacy. But, never for better and occasionally for much worse, he did continue to perform. The singer spent the 1970s trying to fly again, aiming for the heights he reached with his boyhood pal, only to repeatedly fall short. With each failed pass, he began spiraling downwards towards saccharine balladry and 70s chintz. And eventually (though temporarily), he stopped trying altogether.

Many decades later, the name “Garfunkel” is timeless on account of the name that once preceded it: “Simon.” “Art Garfunkel,” on the other hand, is only barely known and almost certainly not for his career as a solo artist. For much of the 1980s, after the echoes of Simon and Garfunkel’s concert in Central Park had faded, he was newsworthy because walked across all of Japan and, then, all of America. Occasionally, he was the guy in an unbuttoned vest, singing behind James Taylor. But, most of all, he was known as the “other guy” in the longest running “he said/he said” in the history of Pop music.

But it wasn’t always that way — far from it. From 1970 through 1973, Art Garfunkel was among the most interesting men in America. Coming off the multi-platinum success of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” he turned his attention to acting, where he made his debut in Mike Nichols’ “Catch-22.” The next year, he was nominated for a Golden Globe in Nichols “Carnal Knowledge.” During this period, from 1971 to 1972 — while also preparing “Simon and Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits” — he somehow found time to teach high school math in Connecticut. The following year, he returned to music, releasing his solo debut, “Angel Clare,” which was certified Gold and produced two top forty singles.

For that brief moment, and likely for the only time in his life, Art Garfunkel was every bit as fascinating as Paul Simon. Maybe more so. It seemed possible that he would go onto a decorated career in film. It seemed equally likely that he’d invent some new musical genre at the intersection of James Taylor and Barbra Streisand. In one, not impossible scenario, he would become the first boarding school headmaster to also sell out summer amphitheaters all across America. For the first half of the 1970s, his unruly frizz of blonde hair looked a lot like a crown.

Following “Angel Clare,” from 1973, Garfunkel released four more albums before the decade came to a close. Three were certified Gold. One went platinum. In 1975, he was the musical guest on “Saturday Night Live.” Five more of his singles reached the top forty in America and “Bright Eyes,” from 1979, reached number one all throughout the United Kingdom. While Paul Simon was earning his bonafides as a critical darling and the second most important American songwriter (behind Bob Dylan) Garfunkel had slowly established himself as the consummate man for the end of transitional decade — sensitive, highly intelligent, romantic, semi-idealistic and, seemingly, terribly depressed.

The years after Simon and Garfunkel were full of high profile, passive aggressive barbs and very occasional, seemingly reluctant collaborations between the boyhood pals. Whereas the more tight-lipped Simon went on to become a lovable, folkie troubadour, interested in rhythm, his former partner appeared somehow more delicate and entirely disinterested in rhythm. While Simon’s solo music would eventually coalesce into “Graceland,” Garfunkel was increasingly stepping into torch song territory. By “Fate for Breakfast” (1979), he was not exactly Barry Manilow or Bette Midler, but he was in the same zip code.

What began as warm possibilities had, by the end of the 1970s, devolved into flaccid melodies and artistic regression. But, it wasn’t simply the trajectory of his musical career or his relationship with Simon. In fact, those were the least of his concerns. In 1979, photographer and actress Laurie Bird, Garfunkel’s romantic partner of many years, committed suicide. Most of America was depressed at the time, but Art Garfunkel was much more depressed. 1981’s “Scissors Cut” was phonographic evidence of that depression — a thoroughly sad album for a thoroughly sad country.

The 1970s were partially defined by melancholic music. Harry Nilsson’s “Without You,” from 1971 was profoundly sad, but it still yearned. Jim Croce and Gordon Lightfoot were depressing, but only in a pensive, folkie kind of way. The Carpenters were, of course, sad as fuck, but their craft was so elegant and Karen’s voice was so pristine that the sadness sounded contained. “Scissors Cut,” however, had the wrong sort of sadness. It had no rhythm. It was not folkie. In fact, it’s often baroque or theatrical. It does not sound like music meant to be pressed and sold on vinyl or performed for fans of Rock and Roll. It sounds like music designed to score a very quiet, very private weeping. To this day, when I hear “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” I can easily be brought to tears. I just can’t help it. But it’s a quick, cleansing sort of cry. When I hear “Scissors Cut,” however, I imagine a too naked, bottomless bawling.

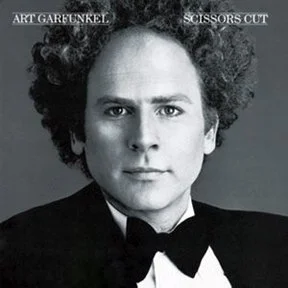

The cover of “Scissors Cut” half-heartedly tries to put on a brave face. We see Garfunkel — chest up, head on — dressed for a night at the opera. The man who was once famous for his black turtlenecks and then more famous for his jeans and unbuttoned vests, appears here, photographed in black and white, wearing a tuxedo. He cannot even muster a smile. The man in this picture is not going to a wedding or a formal dinner. He’s dressed for a eulogy. Before I hear even a single note of “Scissors Cut,” I am certain that it will be zero fun.

Mercifully, the album is short — the bawling is not, actually, bottomless. It’s thirty-two minutes including a two minute epilogue (“That’s All I’ve Got to Say”) and one song (“Bright Eyes”) that he recycled from the import version of his previous album, “Fate for Breakfast.” It is also delicately rendered and evidently thoughtful. Roy Halee, who’d produced many of Simon and Garfunkel’s finest moments, returned to help stave off Garfunkel’s downward spiral. Additionally, Jimmy Webb, who’d written most of the songs from Garfunkel’s last successful record (“Watermark” from 1977), wrote three tracks for “Scissors Cut.” If I were evaluating the album as the soundtrack for a theatrical production about suicide or lost love, I might give it higher marks. But since I am listening to it as “Pop” music and searching for some immediate pleasures, I can only confirm that the record is a slow, steady downer.

To its credit, the singer’s instrument is still intact — his high tenor is consistently, achingly pretty and often doubled and tripled up to create beautiful harmonies. On “A Heart in New York,” he arrives in the big city from a flight from London and marvels at the glory of his home town. It’s mostly a spare track -- fingerpicked acoustic guitar and just a pitter patter for a beat. Garfunkel’s vocals are piled up, affecting something not far from late career Lindsey Buckingham or, even, Sufjan Stevens. It’s sweet and hushed until, midway through, an impolite sax solo interrupts the wistfulness. It’s a shock to the system, the sort of thing that James Taylor increasingly tried and failed with as he got older. The horn doesn’t destroy everything that came before, but it quickly snuffs out any hope for pleasure.

If most of “Scissors Cut” is formally minimal, though, “Bright Eyes” is entirely ornamental. The original was written for an English, animated version of “Watership Down,” ostensibly about one character watching life quickly drain from the eyes of another character. As one might expect, Garfunkel’s version is slow and florid. It’s sentimental, to be sure, but it’s also a perfect fit for Garfunkel’s high tenor and proof that “sadly beautiful” is not necessarily oxymoronic.

Though never “rocking,” the album does make one upbeat pass. “Hang On In” has a (mostly) four/four beat with electric guitar, bass and drums. Written by the guy who wrote Air Supply’s unforgettable “Here I Am,” this track is far more forgettable. The register and pace would befit singers like Christopher Cross or Kenny Loggins -- sensitive, but satisfied, men, singing on board boats or airplanes. Garfunkel briefly tries to sound optimistic, but it's wholly unconvincing.

On the exact other side of the spectrum is “Up in the Air,” wherein our depressed singer and former Pop star finally gives up and eats his feelings. While most of the record at least feigns awareness of Pop or Rock, this one veers headlong into Mandy Patinkin torch song territory. It’s all tenor, actual strings and heartstrings -- a long way from Simon and Garfunkel or, even, James Taylor. Amazingly (depressingly) it’s also, aside from “Bright Eyes,” the most effective song on the record.

“In Cars,” the penultimate song on “Scissors Cut,” is a shapeless, arhythmic, meandering affair -- a lot like depression itself. Drums and trumpets randomly appear, only to be eclipsed by triangle (the instrument) and dull Casio tones. It’s a heavy lift on an album of heavy lifts. However, at the very end of the song -- almost as an aside -- Garfunkel does something surprising. He whispers a quartet from Bob Dylan’s “Girl From the North Country.” And, by the last two lines, he’s fully singing, alongside an acoustic guitar. It’s the first glimpse we get of Art Garfunkel, Folk singer. It’s a promising path, but it’s also a reminder that it’s not the path he ultimately chose.

After “Scissors Cut” and after Simon and Garfunkel’s concert in Central Park, Art Garfunkel took some time to heal. Slowly, eventually, he reemerged. In 1985, amid great intrigue and anticipation, he and Paul Simon attempted to reunite. Simon’s “Hearts and Bones,” from 1986, was originally slated to be the duo’s first album in more than a decade. But, alas, they could not make it work. Garfunkel’s vocals were erased from the mix and he returned to his practice of very long walks, voracious reading and intermittent celebrity. Simon and Garfunkel would, eventually, reunite and tour the world in 2003 and 2004. After years of bitterness and divergent careers, the tour proved to be mostly delightful and uncontroversial. For their fans around the world, the shows were a welcomed tonic -- a romantic capstone to a fifty year old story.

But, of course, it wasn’t really the end. In time, Garfunkel’s solo career, which survived the failure of “Scissors Cut,” underwent something of a reconsideration. He became a name to drop when describing the new generation of romantic folkies — Bon Iver, Sufjan Steves, José González, Iron and Wine, and the like. He published a book of poetry in 1989. And, now and again, Paul Simon would invite his old partner on stage to perform some of their golden oldies together. Art Garfunkel is eighty-one today — ages away from the “Only Living Boy in New York” and nearly as far removed from the dual threat actor-singer who had the world in the palm of his hand in 1971. He doesn’t perform very often, but, when he does, you can still see and hear the man who made “Scissors Cut.” He’s sensitive. He’s precise. He’s a little bitter. And he’s searching. For that other path. Not the canter’s path. Or the architect’s or the teacher’s or the actor’s or the singer’s. The other one.