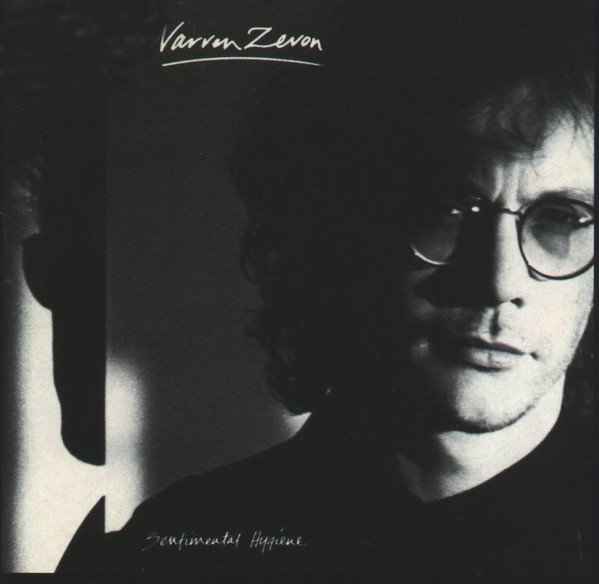

Warren Zevon “Sentimental Hygiene”

A half decade before James Douglas Morrison became The Lizard King, when Laurel Canyon was just a winding road and not a scene, Warren Zevon arrived in Randy Newman’s hometown. Like Newman, who was three years his senior, Zevon was closer to “Jew-ish” than Jewish. Both men are what you might call “literary” songwriters, prone to character studies, historical allusions and biting wit. Both possessed voices that could be described as “interesting” rather than “impressive” or “beautiful.” And, amazingly, both men have eleven studio albums, one top forty hit and one Gold record to their name.

For Warren Zevon, Randy Newman was the bar — the writer turned star who preserved his ideas and integrity. And, in many ways, Zevon reached that bar. Nearly two decades after he passed away, I think it’s fair to suggest that Zevon sits alongside Newman (and probably Tom Waits) on the short list of LA’s greatest songwriters. But for all of their superficial and stylistic similarities, Zevon and Newman could not have been more different. Throughout the first half of his career, Zevon was a renowned alcoholic, drug abuser, womanizer, sex addict and generally pompous son of a bitch. In spite of his relative fame, he was only barely able to sustain himself, and even that was on account to the generosity of his ex-wife, Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Waddy Wachtel, Bruce Springsteen and an extraordinarily devoted cult.

Randy Newman was the opposite — a steady worker who appeared disinterested in celebrity and who moonlit as Hollywood’s most dependable soundtrack artist. Newman had two long, and seemingly successful marriages. If he ever had a problem with booze or drugs, it would seem to have been either short lived or a very well kept secret. Whereas carnage trailed Zevon’s path, Newman’s was decorated with Oscar and Grammy nominations. His thick, untended swath of hair turned charmingly gray as he departed middle age and, even today, he’s still basically the same rumpled guy in an unbuttoned shirt who released “Sail Away” fifty years ago. Zevon, meanwhile, went to great lengths to obscure his follicular challenges — mullets, feathered sides, bangs and ponytails were all involved. And though he stuck to his own shirt and jacket uniform, he tried on a new style every half decade until he died in 2003, at the age of fifty-seven.

Bound together by time and place, it’s no surprise that Newman and Zevon have overlapping audiences: white, older, educated men. But while his commercial success has never matched his critical adoration, Randy Newman never suffered from under-appreciation. Or, rather, you never hear writers or fans complaining about how “under-appreciated” Randy Newman is. Zevon, on the other hand, is the poster boy for the “overlooked” and “underrated” artist. If Randy Newman were described as the “I Love LA guy” or the “Short People guy,” his fans would simply roll their eyes. But when mentioned as the “Werewolves in London guy,” Warren Zevon fans get defensive — bracing themselves for protection or a counteroffensive.

That’s the thing about Warren Zevon that most confuses and interests me: why are his fans so preoccupied with their hero’s “underratedness.” Zevon was about as commercially successful as Newman, and probably slightly more so than Tom Waits. Historically important artists — from Dylan to Petty to Bruce to Fleetwood Mac to REM — lined up to make music with Zevon. In his final year, he was gifted two Grammys and a full, legendary hour on The Late Show with David Letterman. In death, he’s been the subject of countless, existential think pieces. His Reddit community is four times the size of Newman’s (or Jackson Browne’s, for that matter). By my calculations, Warren Zevon seems pretty fairly rated. And yet, anywhere you go on the internet, the conversation about Zevon is ostensibly the same: the world does not sufficiently appreciate the dark, brilliant, tragic genius of Warren Zevon.

So, why is this the case? What is the obsession with “Warren Zevon, Underrated Genius?” The first, and most obvious, answer to that question would, of course, be his music. Loyalists (of which I am at least partially one) simply point to his songs and albums. The riff and the menace in “Lawyers Guns and Money.” The bittersweet ease of “Carmelita.” The uncanny candor of "Desperados Under the Eaves.” In addition to his sense of melody and his song craft, Zevon was equal parts poet, novelist, historian and satirist. And though his discography is perhaps slightly uneven, his songbook is chock full of stunners. If you like Rock music and Pop guile, and if you like to use your brain, Warren Zevon’s pretty darn appealing. That all being said, I don’t believe that the strenuous defense of Warren Zevon is actually about his music.

Maybe it’s his “LA-ness.” With the exception of New Yorkers, people are generally obsessed with Los Angeles. The sunshine. The beaches. The celebrities. The romance. The tragedy. And though Randy Newman owns the city's theme song and though The Doors are the most iconic LA band and though Motley Crue and Gun N’Roses redefined the sound of the town, Warren Zevon is perhaps the most “LA” artist in the history of Rock and Roll.

Part of this is simply timing — Zevon’s 1970s fame coincided with a high time for Hollywood and a terrible time for New York City. Some part was also Zevon’s fashion — the unbuttoned shirts, the fitted blazers and suits, the long hair, the fixed up teeth and gold jewelry. Zevon wasn’t born in LA — in fact, he didn’t really grow up there. But he was reborn there. And he exuded the best and worst of LA as much as any singer or songwriter before or since. However, I can’t earnestly claim that the vehemence of “Zevon-ism” is correlated to his hometown.

Then, perhaps it’s his tragedy that grips us. That he died too soon. But, also, that he was so full of life, until, suddenly, he had none. That he was obsessed with women but unable to effectively love them. That he was an unusually musical, unusually melodic singer, who couldn’t sing very well. That he was brilliant but, in many ways, incompetent. Profoundly insightful but also a black out drunk. Deeply heartfelt in song but frequently callous in life. Though we are all complicated in our own ways, Warren Zevon was the ultimate paradox. But also, I don’t think that’s the root of his fans’ stridency.

What is it then? Are we all just dark motherfuckers who like songs about cannibalistic serial killers? Was “Werewolves of London” so indelible that we feel compelled to justify all the other stuff? Do we have a collective savior complex? I think the answers to those questions are no, no and no. I think the actual answer is much simpler and — for anyone who has ever seen “The Color of Money” — more obvious.

Confidence. That’s the answer. Warren Zevon exuded confidence. Impossible, irrational confidence. In fact, the two most confident performances I’ve ever seen in my life are (1) Tom Cruise in “The Color of Money,” dancing with a pool cue to while “Werewolves of London” plays in the background and (2) every single time Warren Zevon performed on TV.

As for the former, well, Tom Cruise became the biggest movie star in the world and, so, that kind of makes sense. As for the latter, my explanation is less evidence-based but no less sincere. When he performed — at least on television — Warren Zevon just looked confident as hell. Unshakably confident. He played piano with incredible force — like he owned the goddam instrument and didn’t care if he broke it, but also like he could never break it because he was a master. He played guitar, his second instrument, like he was Eric Fucking Clapton, even though he couldn’t play like Eric Clapton. His baritone voice, though limited in range, was heavy and steady — the voice of a leader. Whatever he sang, you tended to believe it.

But also, the way he looked — scraggly hair and beard, bad skin, kind of sleazy. He was no matinee idol and, yet, he seemed so sure of himself. He looked nothing like Tom Cruise. Cruise is near billionaire with a face that opens movies while Zevon died with nothing but the value of his songbook. But those are the two most confident men I’ve ever seen. And maybe that’s our obsession. And maybe that’s why we can’t get past his underratedness. Compared to Tom Cruise — yes — Warren Zevon was underrated.

Following the unexpected success of “Excitable Boy,” Zevon’s commercial prospects began to fade — quickly. “The Envoy,” from 1982, was predictably literate, frequently dark and occasionally brilliant. But, also, it flopped. Zevon’s critical adoration barely wavered. His tried and true loyalists stood and applauded. But the rest of the market — radio stations, record stores and casual listeners — lost interest. Within a year of its release, Zevon was a black-out drunk divorcee, dropped from his record label and going nowhere fast.

It would be five more years before Warren Zevon released another album. In the interim, he licked his wounds, tried, failed, tried again, failed again and — eventually — succeeded in getting sober. For most of his time away, Zevon was not terribly missed — he was, after all, more of a cult figure than a celebrity. But then, in 1985, while Tom Cruise sashayed around the billiards table like a ninja pool hustler, Martin Scorsese dropped the needle on “Werewolves of London” and people suddenly started talking about Warren Zevon again.

Two years after “The Color of Money,” the newly sober, semi-apologetic singer-songwriter returned with “Sentimental Hygiene.” Zevon’s return was both a redemption story (damaged genius gets sober and cleans up his life) and a reclamation project (media and celebrity friends gather around damaged genius to demonstrate admiration). Unencumbered by alcohol and unconstrained by commercial expectation, “Sentimental Hygiene” was also Zevon’s moment to graduate from “criminally underrated” to “adequately adored.”

He was not alone in the quest — far from it. Friends, fans and peers seemed even more invested in Zevon’s reputation than the singer, himself. And so, as had been the case throughout his career, people lined up to help. But this time, the line was longer and more celebrated. “Sentimental Hygiene’s” backing band was REM (minus Michael Stipe) who, in 1987, were the most darling of critical darlings and just weeks away from their own commercial breakthrough (“Document”). And filing into the various studios, alongside Zevon, Mike Mills, Bill Berry and Peter Buck, was a “Who’s Who” of Rock stars and celebrity session players: Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Don Henley, Flea, Mike Campbell, Waddy Wachtel and — well — you get the point.

On the surface, “Sentimental Hygiene” is a vulnerable, post-carnage, post-rehab album. But the subtext — or meta-text — is about “Warren Zevon, underrated artist.” The album’s stories range from familiar to academic — most of them about Zevon, one about a boxer, one about a factory town and one about colonial Kenya. But, in retrospect (and maybe even at the time), the album signified much more than the sum of its stories. Zevon’s return was validation that he “still had it” and that what he had would not, should not, could not be underrated nor overlooked.

It almost worked. As a commercial reclamation, “Sentimental Hygiene” outsold its predecessor and managed to sniff the Mainstream Rock radio charts. The inclusion of REM, not to mention the parade of Hall of Famers, made for great press releases — the copy practically wrote itself. It capitalized on the momentum from “The Color of Money” and set up Zevon for a solid second act and legendary, if tragic, third act. Additionally, the collaboration with REM re-situated him just to the right of “Alternative” and just to the left of “Boomer Genius.” Basically, in between Tom Waits and Randy Newman — precisely where he wanted to be. At the time, among his English professor acolytes, his celebrity friends, the critics who hailed him and his new twenty-something hipster fans, Warren Zevon was the opposite of underrated.

As for the album itself and whether it warranted all the hoopla, the answer, I think, is “mostly yes.” With the exception of one electro-synth track about the rebel spirit of mid-century Kenya (“Leave My Monkey Alone”) “Sentimental Hygiene” plays no tricks. The album does not particularly sound like REM. Rather, it sounds “of its time” in that there’s notable reverb in the vocals and that the guitars are more prominent than the piano. But, on the whole, it is the very well written and very well made album that you’d expect from mid-career Warren Zevon. The singer’s voice showed no signs of degradation — it’s still plenty deep and heavy. The hooks are direct and concise. The playing is uniformly expert. And the words are astute. It’s not lyrical and literary like his debut or fearless and frightening like “Excitable Boy,” but it is, by any standard, a very good (possibly great) Warren Zevon album.

It almost goes without saying that Zevon possesses many gifts as a songwriter. The cogency and efficiency of his guitar riffs are extraordinary — there’s a reason why “Werewolves” and “Lawyers, Guns and Money” are unforgettable. He’s also a gifted leader of bands, having performed that function for The Everly Brothers for many years and for David Letterman on occasion. He knows how to get his band to sound the way it should sound. But, it’s probably the range of his storytelling techniques that most impresses me. Drunk or sober, young or not young, Warren Zevon could convincingly go from dark satire to literary non-fiction to something deeply personal and emotive.

“Detox Mansion,” with its limo drop offs and leaf sweeping next to Liza Minnelli, checks the satire box. It’s got a too good to pass up title, a great vignette and rock solid bass hook that does not quit. Further, it manages to paint the singer as both entirely knowing and kind of pathetic at the same time — no small feat of writing. “Even a Dog Can Shake Hands,” a Mellencampy Heartland rocker about an industry of hand-shakers and deal-makers, is not a perfect fit for the singer but every bit as funny as “Detox Mansion.” REM strums up a great jangle but the pace and its lightness betray the noirish weight of Zevon’s baritone. Petty could have had some fun with it. Five years earlier, The Clash could have made it something special.

As for the non-fiction, “Boom Boom Mancini” is (how can I not?) a knockout. The riff is so heavy that, if played faster and louder, it might even sound like Heavy Metal. But, rendered mid-tempo and without much distortion, the guitar, bass and drums sound, appropriately, like a steady, landing jab. While I love Dylan’s “Hurricane,” I think Zevon’s boxing epic is both more fun and less flinching.

And that leaves the personal stuff. Like Randy Newman, Zevon always seemed to prefer character and story to memoir and confession. But, with a bag full of regrets and handfuls of apologies, Zevon eschewed the old barfly tales in favor of more personal candor. The bluesy title track finds Zevon slowing down, leaving the bottle behind and acknowledging that he needs more than a little self-care. It’s a solid opener and true statement of purpose.

Meanwhile, “Reconsider Me,” while not the title of the record, is probably the album’s unspoken headline. Over a jangle that’s more Petty than REM, Zevon asks us all — his ex, his kids, all the other women, his fans and anyone else who’s listening — to give him another chance. He’s trying to convince someone he knows and loves that he’s not a closed off, shut down, blacked out, broken down cynic — that he has an open heart. But, simultaneously, he’s telling us all that he’s not a has been or a could have been — that he’s vital and vulnerable and, yes, still worthy of our love.

In spite of its context and its vulnerability, “Sentimental Hygiene” is not a diffident album. The weight of Zevon’s voice and his playing cannot not project confidence. But, I do think it’s the closest we ever got to Warren Zevon — just the guy — rather than Warren Zevon — the brilliant writer of characters. For most of the Nineties, Zevon returned to satire and non-fiction, frequently writing alongside esteemed authors and journalists. But, the man who made this album was asking something of us, a gesture which he was unaccustomed to and which we might not have expected.

For the balance of his career — at least on record — he did not return to bended knees. Even in 2003, on “The Wind,” when he was staring down death and thinking about his legacy, Zevon asked nothing of us. Dying Warren Zevon was resolved. He didn’t ask why. Even when he gave Letterman that final hour — when he told us to “remember every sandwich” — he sounded much more resolved than lost.

That version of Zevon — 2002 very special Letterman guest — is Warren Zevon signified: underrated, stoic genius with celebrity superfans. I understand it, but I don’t buy it. At least, not fully. If “Sentimental Hygiene” is even partially true, I think that he was fairly rated and carefully observed, and that his confidence was more mythical than mythic. If you know what I mean.