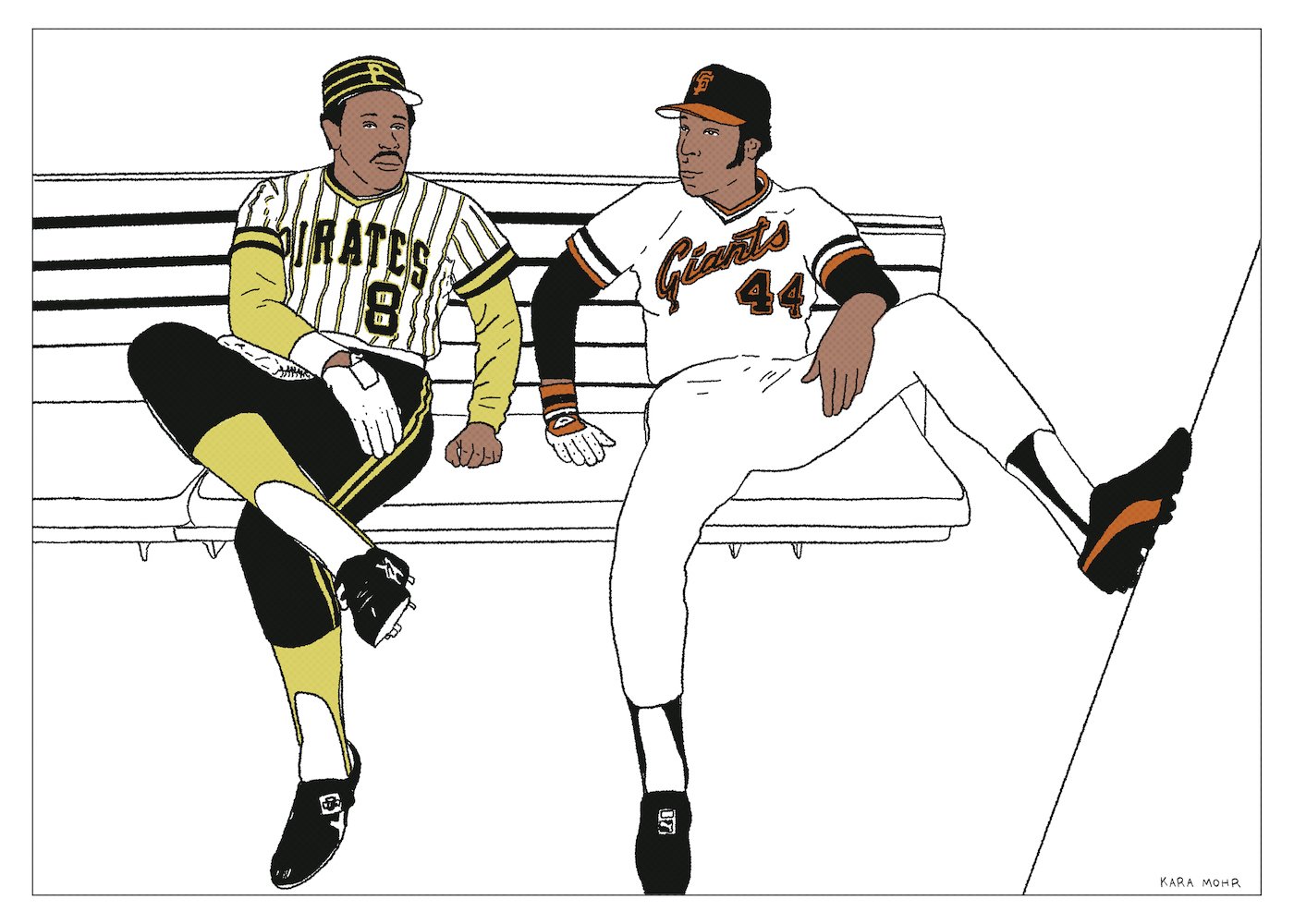

Willie McCovey and Willie Stargell “The Other Willies”

Beyond their shared first name and their doppelgänger stats, McCovey and Stargell co-represent an enduring Major League Baseball archetype: post-Jackie-and-Larry, post-Hank-and-Willie MLB stars. Stretch and Pops were MVP, Hall of Fame sluggers young enough to appreciate the monumental importance of their predecessors and old enough to recall the ugliness of baseball’s recent past. The two Willies respectfully thrived so that Curt Flood could brazenly protest. They demurred so their superstar teammates—Mays and Clemente—could shine. If Willie Mays was always the untouchable standard, McCovey and Stargell—together—represented the enduring greatness of goodness.

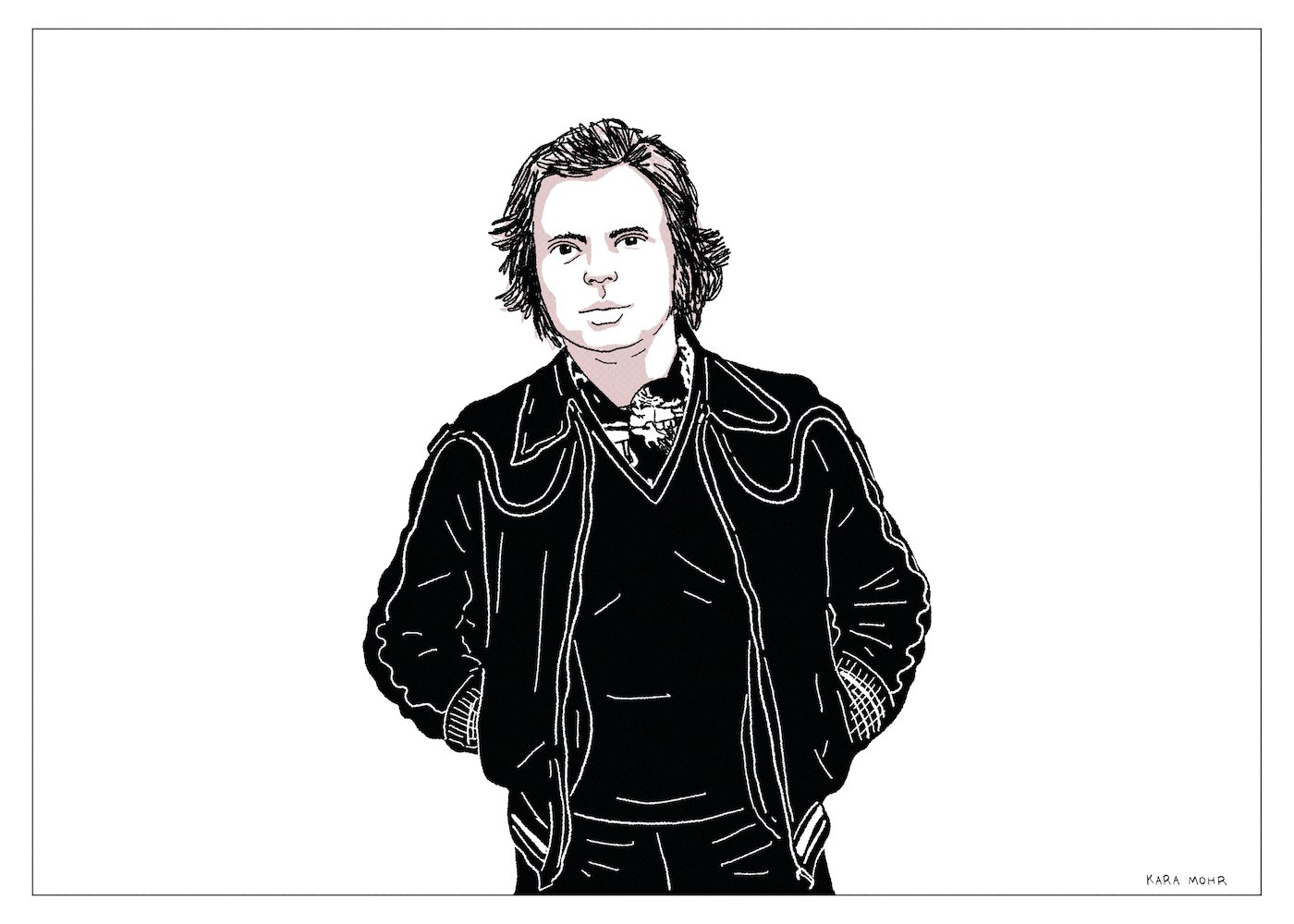

Van Morrison “The Album Covers”

Before he became a craggy, portly Soul man in fedoras and suits, before he was a grumpy anti-lockdown militant, before the Skiffle record and the Facebook rant and a song so profoundly sad (“Pretending”) that it was somehow more depressed than his song about walking out on a friend with tuberculosis (“T.B. Sheets”), before the healing and the silence and the hymns, and before he stuffed himself into that stretchy leisure suit get up for “The Last Waltz,” George Ivan Morrison cared deeply about his album covers. But that was then. Today, Van survives as the artist whose album cover art most betrays the product contained within. His obsession with “tone” and “feel” is surpassed only by the depth of his disdain for the art that adorns his music.

Dave Parker “The Masked Cobra”

Jim Rice stood six feet, two inches tall and weighed two hundred pounds. At the plate in Fenway, he looked like the perfect slugger. But, next to Dave Parker, he looked like Rocky standing beside Drago. By the late Seventies, Pops Stargell was the same height as Rice, but with fifty pounds of excess gut. And yet, next to The Cobra, Stargell looked like Santa hanging out with The Incredible Hulk. Dave Parker was not the greatest player of his era, but for several seasons, he might have been the most important — and the most feared. On July 16 1978, two weeks after breaking his cheekbone in a home plate collision, The Cobra returned to the line-up wearing a very basic, but entirely frightening, half white, half black protective mask designed for hockey goalies. As he made his run towards a batting crown and the MVP award, Parker looked not unlike Jason Voorhees dressed as a giant killer bee.

Miles Davis “Jack Johnson”

Recorded less than six months after “Bitches Brew,” “Jack Johnson” is as much a tribute to Betty Mabry, Davis’ former wife and muse, as it is to the titular heavyweight champ. Mabry was a Free Funk pioneer, and friend of Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone. With his increased interest in Mabry, came Miles’ increased interest in electric instruments, in general, and distortion and Funk, in particular. Experimental music and progressive politics, however, represent roughly half of the ingredients in “Jack Johnson’s” potion. The other half of the is made up of the sweat of legendary boxers and, of course, cocaine.

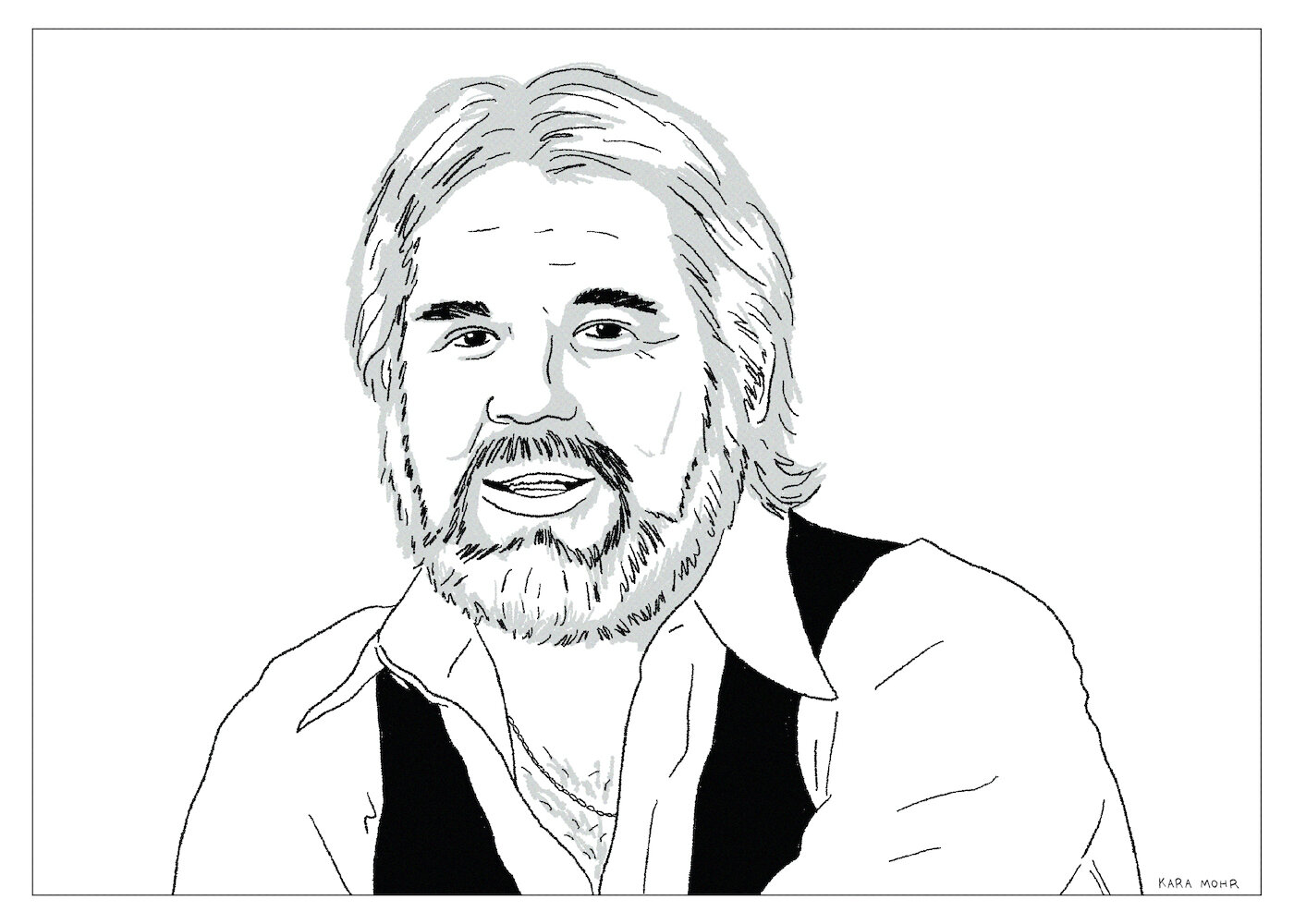

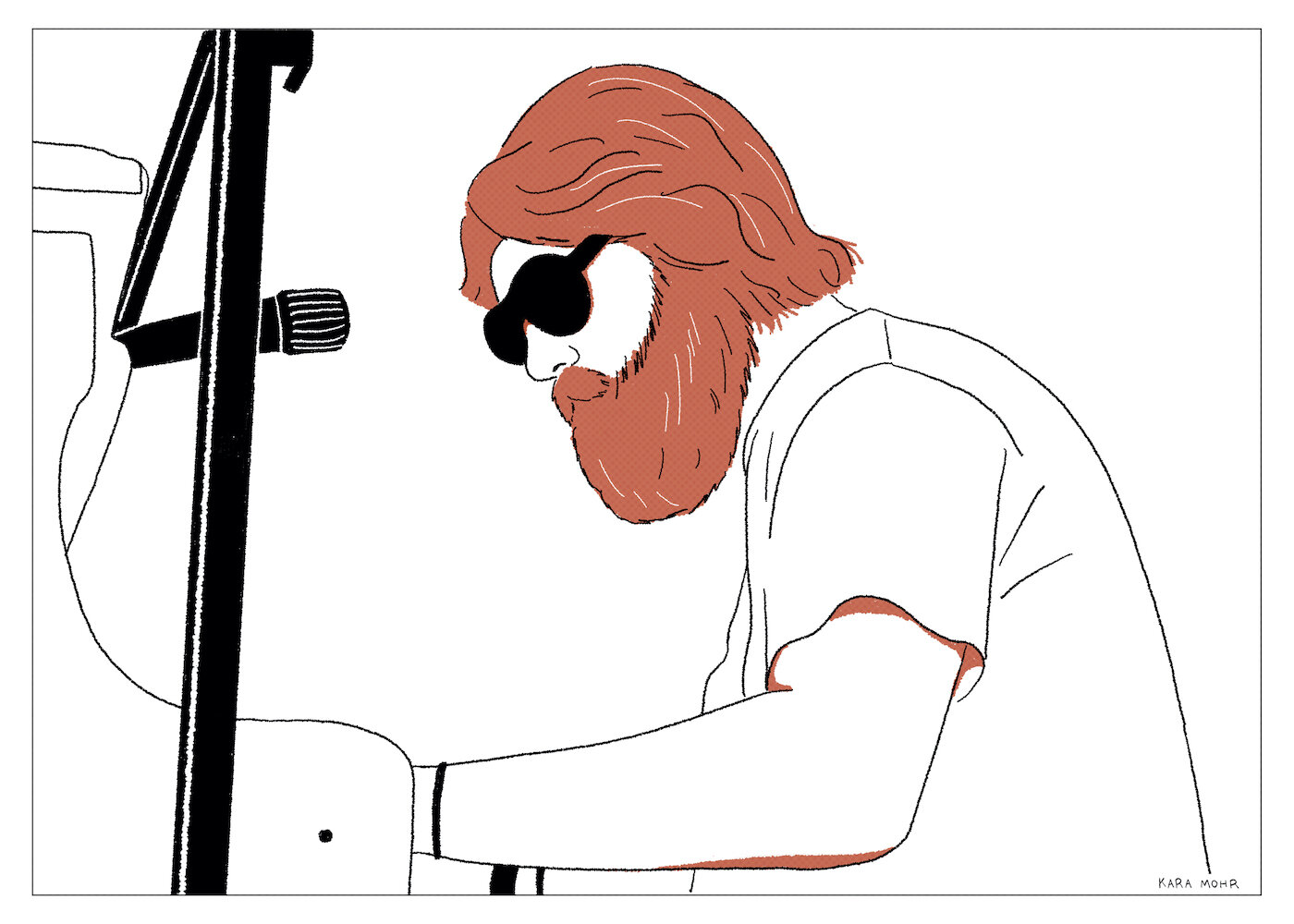

Kenny Rogers “Kenny”

Kenny Rogers’ appeal was one of masculine kindness. At his best, his voice lands somewhere between Lionel Richie and Bob Seger on Valium. And on 1979s “Kenny,” he put that bearded charm and “Gambler” equity to work for a lovely, schmaltzy set of lite Country Pop that would go on to sell twenty million copies worldwide. Yes — in 1979, Kenny Rogers was very nearly Michael Jackson.

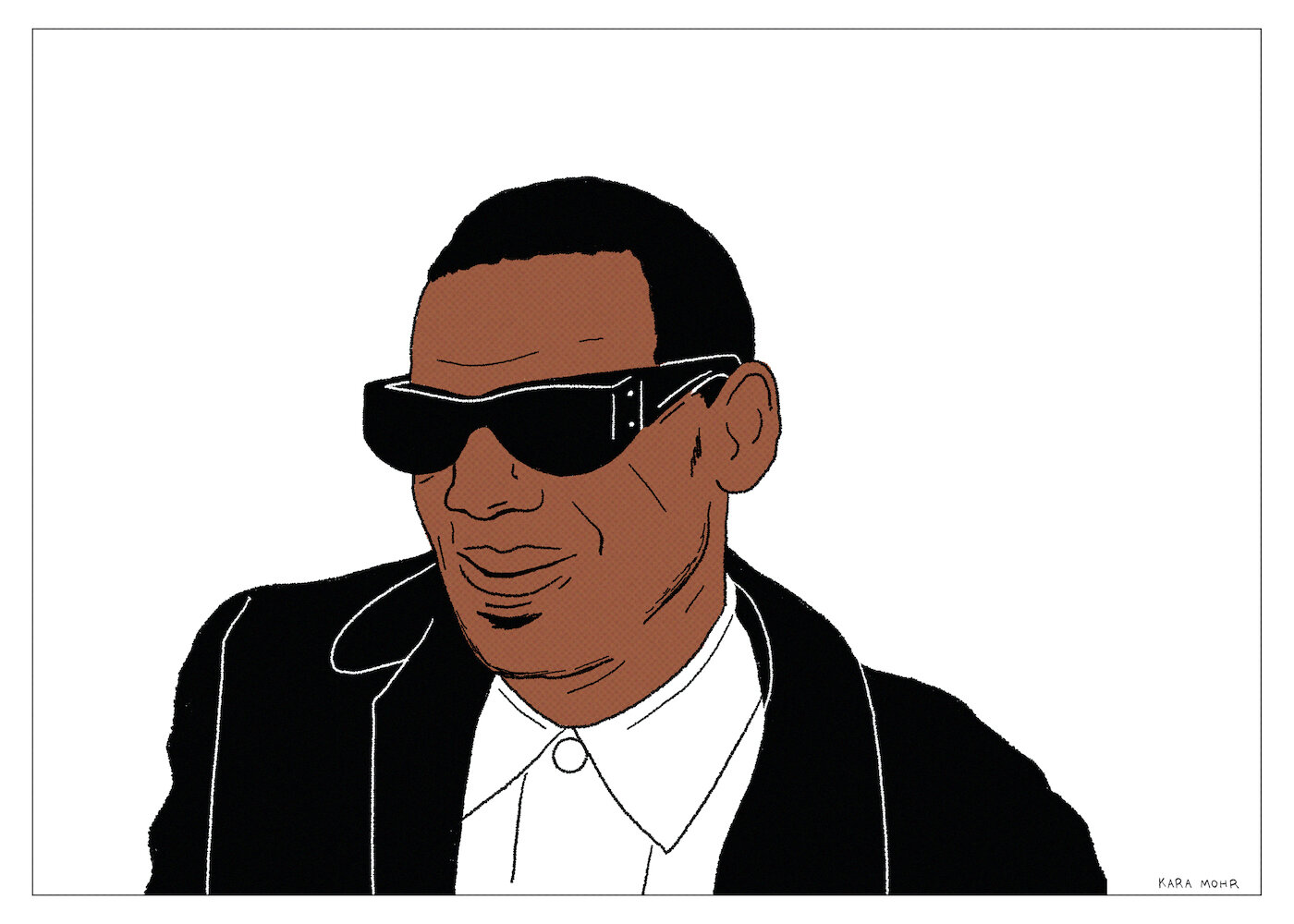

Ray Charles “True to Life”

The 1970s saw Ray Charles’ sales dwindle, his chart success regress and his critical adoration fade. And the Ray Charles who signed with Atlantic Records in 1977 was not the same one who signed with the label twenty five years earlier. This one was sober, divorced, a millionaire and forty-seven years old. Fans and critics still hoped that Ray would find some new inspiration, but, those hopes would be repeatedly dashed. 1977s “True to Life,” like most of Rays’ albums from the 70s, reveals a restlessness much more than a breakthrough.

Bill Withers “‘Bout Love”

Bill Withers wrote concise songs about simple ideas, added uncomplicated melodies and let his band do their jobs. He simply never wasted a note. By 1978, though, Withers was almost already done with it all. He still had enough cache to make one final record on his own terms. “‘Bout Love” sounds like an artist carefully packing up his desk for an early retirement.

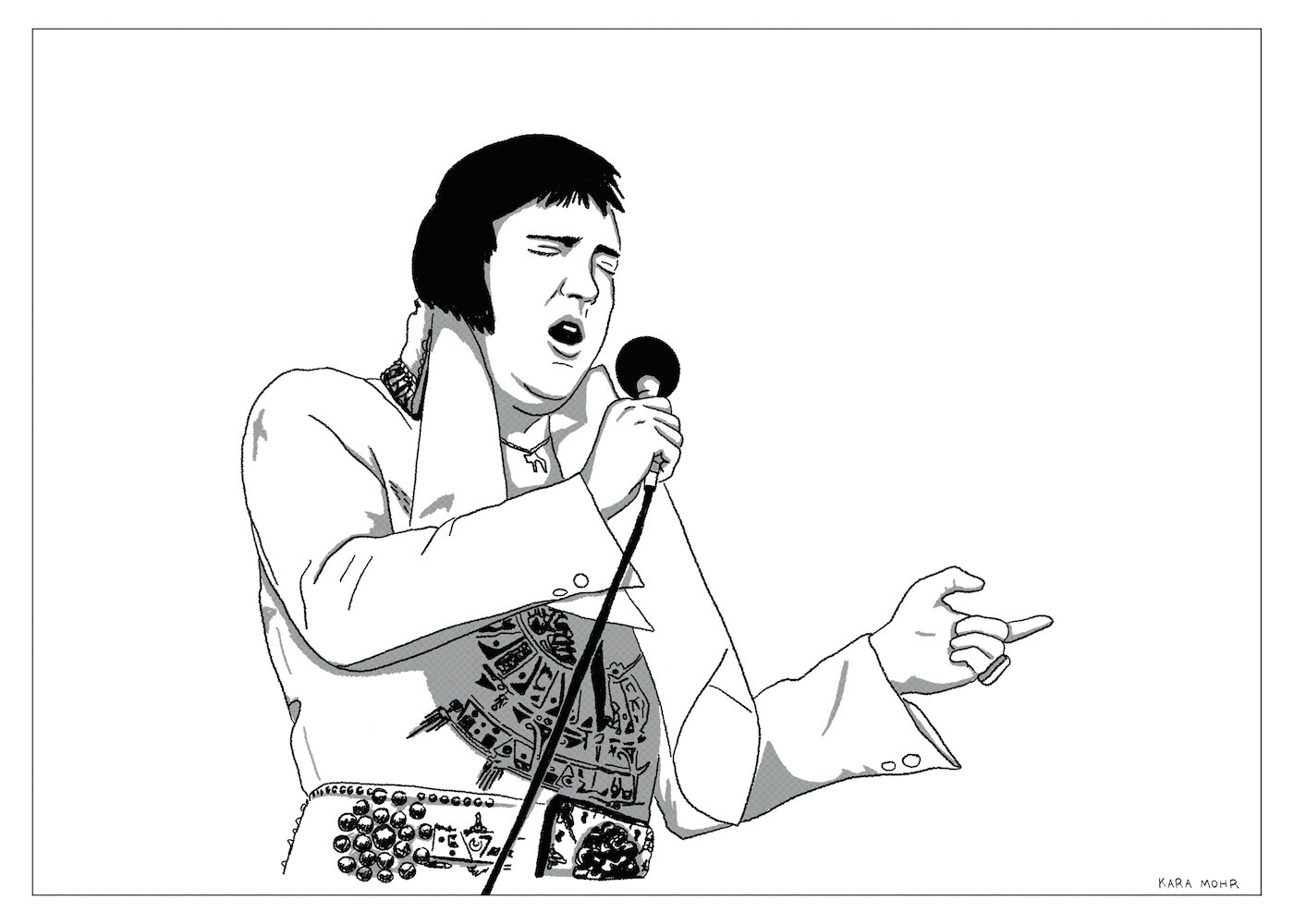

Elvis Presley “Moody Blue”

Elvis wore the white jumpsuit on stage for seven straight years. It flexed with his changing size. If it didn’t, he got one that did. He was the first rock star and the original past prime poster boy. He was only 42 when he died in 1977, but in the cultural memory he was a bloated, pill popping monster who died on the toilet. It was really not long ago that he was just the boy from Tupelo. The one who didn’t like to perform in public but had the golden voice.

The Beach Boys “The Beach Boys Love You”

Promiscuity and excess have been the gold standard for rockers running in terror from the middle age slump. But there’s a less commonly utilized strategy that can be effective: regress farther. Past adult, past teenager, past kid. Go full baby. Wear only a bathrobe, write a song called “Ding Dang.” Build a sandbox in your bedroom and put your piano in the middle. Take one listen to “The Beach Boys Love You” and you will know that Brian Wilson alone conceived this deeply personal, bat-shit, Beach Boys in name only album.