Phish “Fuego”

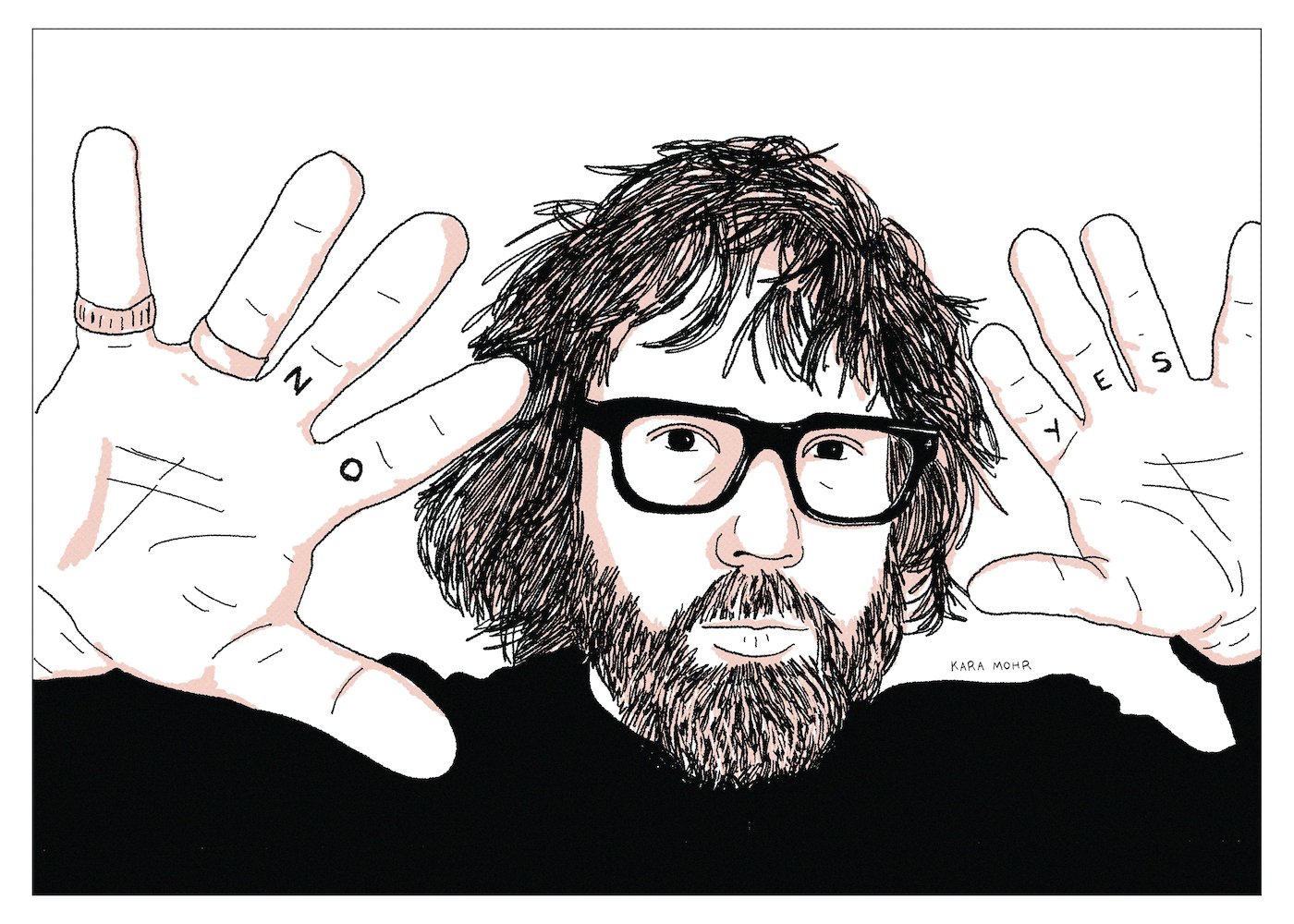

I have a Phish problem. Or at least, for the last thirty years I’ve told myself that I have a Phish problem. This problem is in spite of my adoration for the state of Vermont. In spite of my having seen Phish perform live multiple times. In spite of being occasionally, but earnestly, wowed by the wizardry of their jams. In spite of my appreciation for their business acumen. In spite of my loving their Ben & Jerry’s flavor. Yes — in spite of all of it — I don’t abide. Which, for most people, would not be such a problem. But, as a Vermonter at heart, I am left with this unrelenting pull between my Yes-Vermont soul and my No-Phish conscience. It is a battle that, until recently, I had ignored. But it was a battle that I knew — someday, somehow — I’d need to resolve.

Pitchfork “0.0”

It’s been a couple of weeks since Condé Nast’s decision to reorganize and downsize Pitchfork, a move that drew head scratching disbelief and foot stomping ire from everyone with an opinion on the matter. As with all corporate shake-ups, the full implications won’t be understood for some time. But what is knowable now, and for certain, is that (a) many people lost their jobs and (b) Pitchfork was one of the first Condé Nast titles to successfully unionize and (c) the writing at Pitchfork was never better than it had been recently, under Editor & Chief, Puja Patel. Meanwhile, what should have been known to Anna Wintour (Condé Nast Chief Content Officer), Roger Lynch (Condé Nast CEO) and Nick Hotchkin (Condé Nast CFO), is that nobody under the age of fifty gives a shit about G.Q. (the title that Pitchfork was reorganized into) and that many people give many shits about Pitchfork.

Rush “Vapor Trails”

By the time I reached middle age, my longstanding, polite refusal of Rush had settled into a wizened indifference. In fact, since I was not a subscriber to Guitar World or Drummerworld magazines, many years would go by without me hearing a peep about the band I’d once tagged “Loser Van Halen.” But then, one day, I caught wind of “Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage,” a documentary that was generating buzz on the festival circuit. That buzz swelled, culminating in awards, which begot a short theatrical run, which is where, in the summer of 2010, I was confronted with the most unfathomable of questions: What if the band I liked the least was the one I loved the most?

Bry Webb “Run With Me”

Some bands are corporations, like The Rolling Stones. Some are communes, like Big Thief. Some are gangs, like The Clash. The Constantines, however, were more like a union — the genuine article. They were brothers in arms, in jeans and flannel. But when their mission inevitably bumped up against the realities of family and finance, the union dissolved. The miracle was not that The Cons broke up. The miracle was that they were so true and so committed for as long as they were. Just four albums. Not even a decade. But they never stopped waving the flag. Never stopped working. Which is why Bry Webb needed a break. Why, first, he left for Montreal. And then to Guelph, outside Toronto, where he started anew — as a husband, a college radio programmer and the maker of quiet, plaintive songs about the glow and glare of new fatherhood.

Kevin Drew “Aging”

Since “You Forgot It in People” — the record that a generation made out to and broke up to — every Broken Social Scene album has been an event. The reveal of who’s in and who’s out and the inevitable comparisons to their masterpiece. But while they have all been events, they have been more so celebrations. For all of the gothic romance of “Lover’s Spit,” Kevin Drew sure seems like a jubilant fellow. “Hug of Thunder” is his brand. He’s the glue and the vibes. But he’s also a guy who exists outside of his collective. In between those BSS records, Drew has been releasing lower stakes solo albums. Initially, with many members of Broken Social Scene. Then with a few. And then, finally, all alone.

Coldplay “Music of the Spheres”

And that was the thing about Coldplay — they were fine. Extremely so. But, also, just so — fine. Their bug — a complete lack of tension — had become their undeniable feature. Even in divorce, Chris Martin managed to avoid friction, co-describing his split from Gwyneth not as a divorce or a break-up, but as a “conscious uncoupling.” However, where their consistency was once considered a strength, in time people began to whisper about their boring sameness. At the height of their ascent, Martin had quipped that Coldplay needed to focus on getting better, not bigger. By the second decade of the twentieth century, however, they were neither better nor bigger. They were more hovering blimp than soaring rocketship.

Night Ranger “Somewhere in California”

What happens to our dreams in middle age? Do they still matter? Were they silly to begin with? These are the questions we wrestle with on the other side of forty. And, as much as Night Ranger were an Eighties Rock band, they were also a middle-aged Rock band. Strictly speaking, they were more the latter than the former. While they released five albums during their heyday, they — amazingly — have put out eight albums since. Their most recent album, from 2021, was “A.T.B.O.,” an acronym for “And The Band Played On.” Its predecessor, from 2017, was entitled “Don’t Let Up.” The evidence suggested that Night Ranger wasn’t simply “hanging on.” That they were not content being “the Sister Christian guys.” That there was a destiny yet to be fulfilled.

Barry Manilow “Here at the Mayflower”

Barry Manilow has sold more than eighty-five million albums — that’s more than Tom Petty, Nirvana or KISS. Once upon a time, he was the yellowing wallpaper of American music. For the better part of a decade, his songs were all over the radio, in grocery stores, waiting rooms and elevators. But, by 1984, years after “Mandy,” he’d hit a wall. Yes — the man who wrote the songs (but who I later learned did not write “I Write the Songs”) stopped writing the songs. After “2:00 AM Paradise Cafe,” it would be another twenty years before Manilow produced another album of originals. When he did, though, it was a doozy. “Here at the Mayflower,” from, 2004, was the apotheosis of Barry Manilow — an album of Swing, Mambo, Pop, Disco and Cabaret tunes about the apartment building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn where he grew up. It was the record that Terri Gross and Oprah Winfrey desperately wanted. It was the concept album he was born to write.

Joe Cocker “Heart and Soul”

“Heart and Soul” was Cocker’s response to Johnny Cash and Rick Rubin — simple arrangements of classics, alongside unexpected takes on Modern Rock. Cocker, who had not flirted with contemporary material in decades, decided to cover (like Cash) U2’s “One” and R.E.M.’s “Everybody Hurts.” But unlike The Man in Black, who mostly talk-sang his way through the “American Series,” leveraging the bottom of his one octave range, Cocker pushed the upper limits of his instrument. He was like the aged athlete attempting to match the records of his youth. Like Carl Lewis trying to run a sub ten second 100 meter sprint today, at the age of sixty-two. Joe Cocker could obviously not sing in 2004 like he sang in 1969. But that was the humanity and the tragedy of this project. On occasion, it was touching and beautiful. Elsewhere, though, it was like watching a former Olympian tearing their achilles and then still gutting out the race, howling and limping their way to the finish.

Goo Goo Dolls “Magnetic”

“Magnetic,” the Goo Goo Dolls’ tenth studio album, was a choice — less left, less right, more middle. The ballads inched closer to Coldplay. The rockers closer to Mumford & Sons. It was a direction the Goo Goo Dolls would stick with in the future, introducing tasteful whispers of contemporary Rock and Pop into their road tested formula. But it was never more than a whisper. And none of it seemed to matter much because their fate had been sealed many years before — frozen in amber along with the Clinton Lewinsky scandal, McGwire and Sosa’s home run chase and John Rzeznik’s blonde highlights. For two decades, they have signified “late Nineties Modern Rock that is in no way Alternative Rock.” They are the apotheosis of the form — the very best at it. And yet, in 2013, 2017 and 2020, they were destined to end up on a float in Manhattan for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade for the most obvious of reasons: November is pumpkin spice season.

The American Analog Set “For Forever”

Though they broke up in 2008, The American Analog Set started hanging out again in 2013. They’d meet up weekly and play music for the purest of reasons — because they enjoyed being together. It was familiar and comfortable. But in no way did their weekly jams sound like a reunion or even a precursor to a reunion. On the other hand, it did beg the question: If a band plays in a living room for no one but themselves, are they even a band? If a tree falls in a forest, does it make a sound? In truth, nobody knew about these private get togethers and so nobody was asking. But then, a year or so ago, the fading flicker made a pop. Numero Group announced plans to reissue the first three Analog Set albums. A lost track came to light. And then, seemingly out of nowhere, The American Analog Set, who were always as much a dream and a mystery as they were a band, revealed “For Forever,” their first album in eighteen years.

Loverboy “Unfinished Business”

Peak Loverboy is the sound of producer, Bruce Fairbairn, and engineer, Bob Rock. So is peak Bon Jovi. So is second peak Aerosmith and fourth peak AC/DC. It’s a big sound — heavy but not pummeling, bombastic but not ridiculous. It’s also a clean sound — every instrument has its place. It was their knob turning that made Bon Jovi sound like making out, Def Leppard sound like getting off and Loverboy like dry humping. As good as Loverboy was, their brief and unfathomable greatness was really that of their producer and engineer. A quarter century after their heyday, though, without Fairbairn or Rock, Calgary’s finest Arena Rock band returned one more time, as though to prove to Bon Jovi and Def Leppard who really came first.

The Hold Steady “Thrashing Thru the Passion”

Of course we loved them. How could we not? After The Strokes and Interpol we needed something seriously less serious. We asked, and Saint Paul answered with The Hold Steady, a bar band that was also a bard band. Five guys who liked to drink and who sounded like Thin Lizzy covering The E. Street Band covering “Tangled Up in Blue,” but with Randy Newman on vocals. Three albums in, they represented everything that was great about Brooklyn. Three albums later, they seemed more like the downside of gentrification. Album number seven, however, which was released five years after their disappointing sixth, was a triumph — a recollection of where they had come from as well as an honest assessment of the price of progress.

No. 2 “First Love”

Soon after the breakup of Heatmiser, Elliott Smith was an internationally renowned, critically adored singer-songwriter. But less than five years after his breakthrough — after he stood nervously on stage in a white suit, singing “Miss Misery” for some of the most famous people in the world — Elliott Smith was dead. By that point, his former bandmate and college buddy, Neil Gust, had moved from Portland to New York City, where he gave up his rock and roll ghosts and let the bruises of Heatmiser fade. Gust traded in his band for a three person domestic partnership, and traded in his guitar for a video editing suite. The man who was once Elliott Smith’s closest friend and who was, for a time, also considered his songwriting equal, became a successful commercial video editor. But nearly twenty years after his last record, when he was fifty years old, Neil Gust returned to Portland and started making new music again.

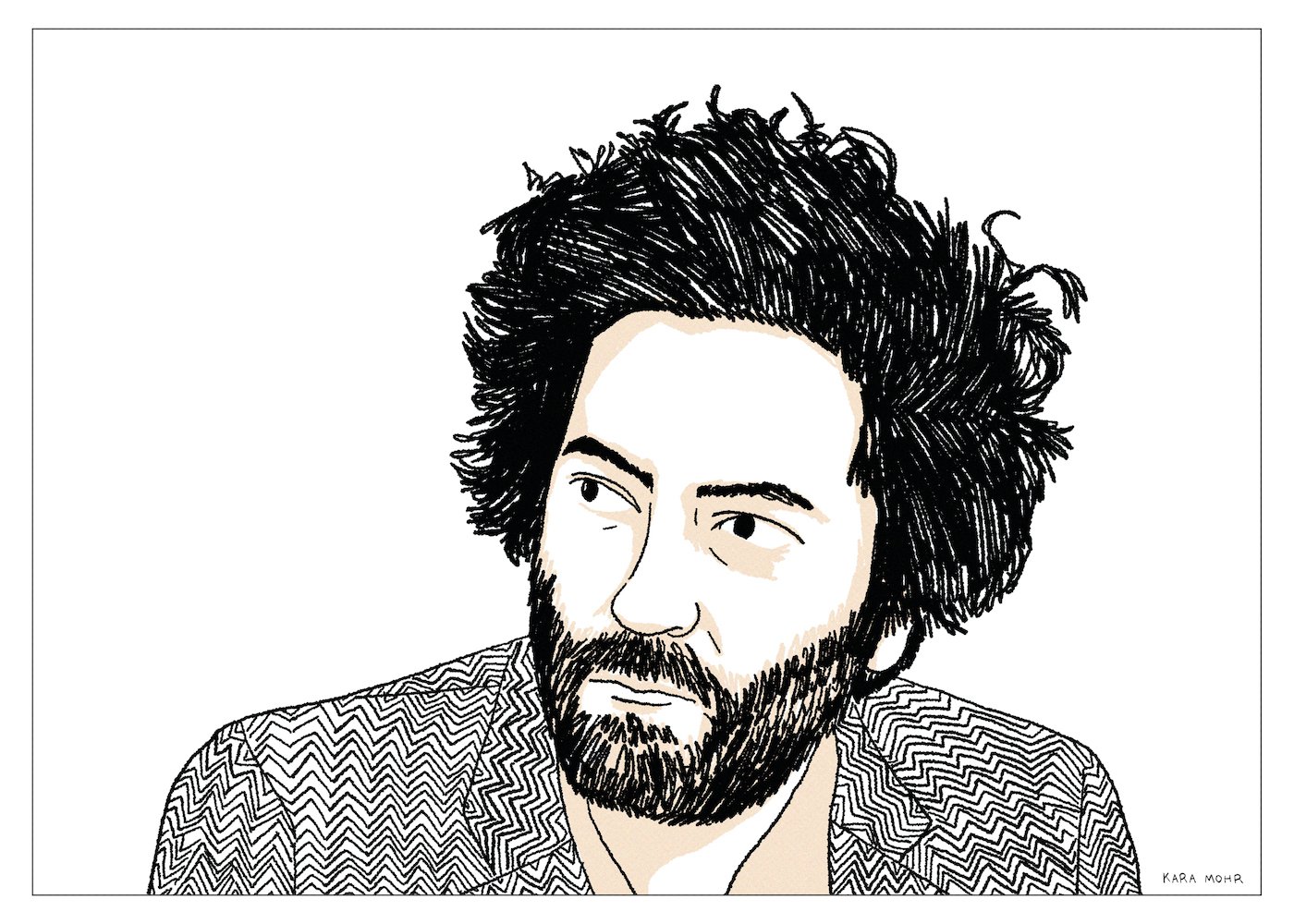

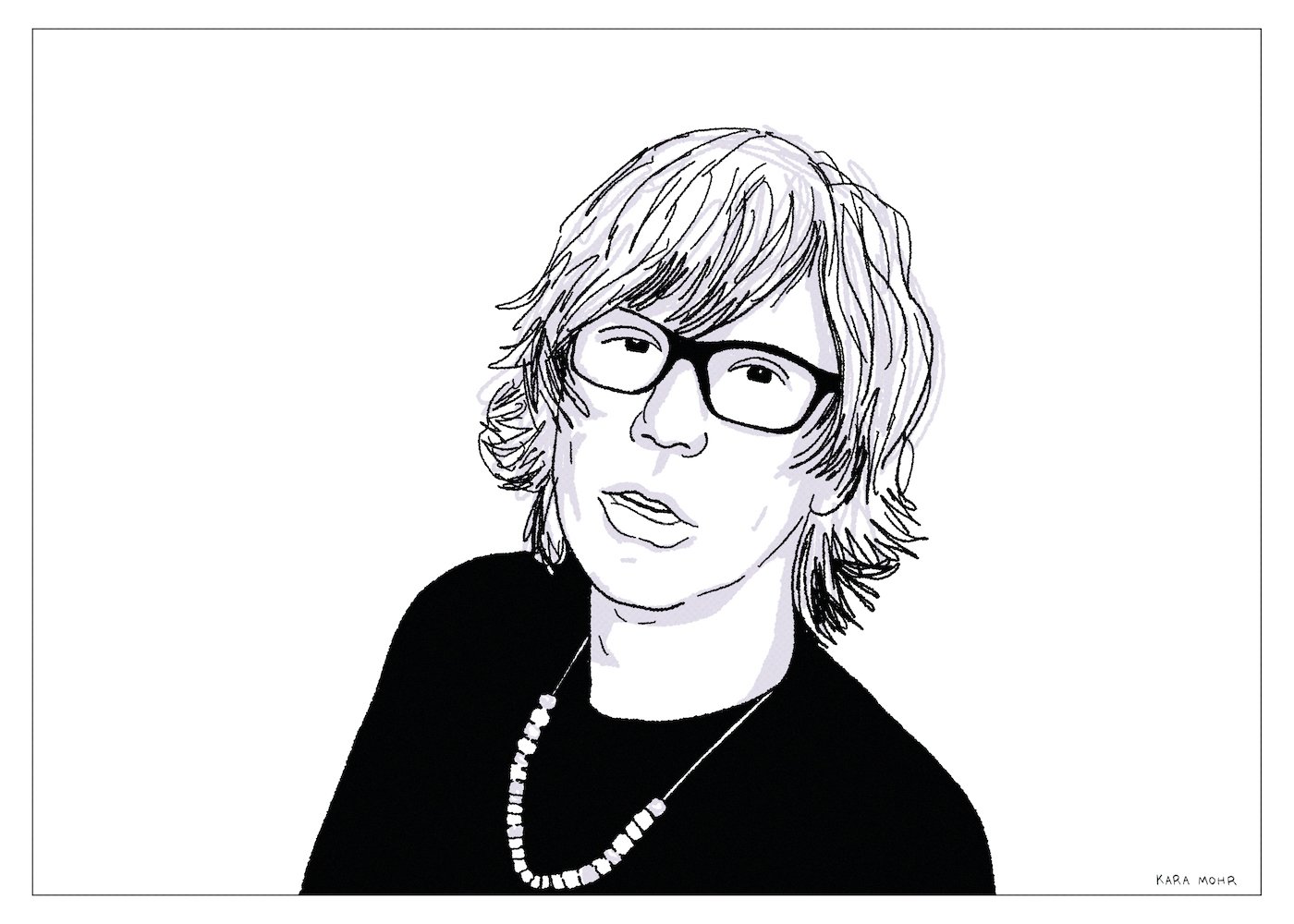

Destroyer “Have We Met”

Destroyer’s ninth studio album, “Kaputt,” was the rare album that succeeded poolside at boutique hotels as much as it did inside Urban Outfitters as much as it did at grad school cocktail parties. In the career of Dan Bejar, and in spite of everything he had accomplished before — with Destroyer and with The New Pornograohers — there was “before Kaputt” and “after Kaputt.” After “Kaputt,” a lot changed. Bejar got semi-famous. His clothes got fancier. His hair got bigger — and slightly grayer. Strangers wanted to talk to him. People wanted to hear what he had to say. And, moreover, what he meant. Was he really a master making masterpieces or was it all just artfully arranged, magnetic poetry from the most interesting man in North America?

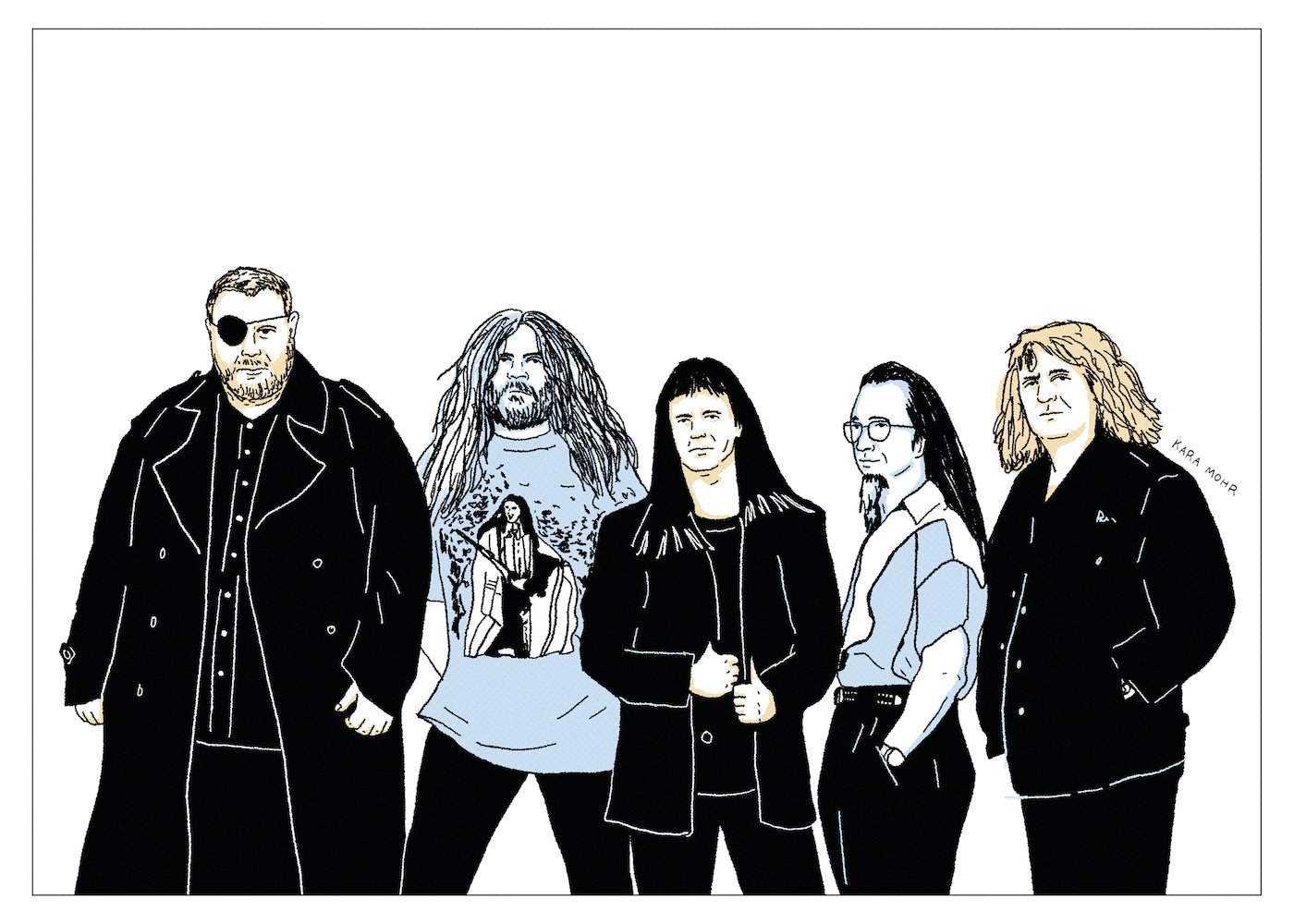

Kansas “Somewhere to Elsewhere”

Three decades in, when “Dust in the Wind” was exactly that, Kansas was floundering mightily. Next to Styx and Journey, they almost made sense. But after Michael and Prince and GnR and Nirvana — Kansas seemed like the greatest accident in the Classic Rock canon. A legendary Arena Rock band that was actually a Prog Rock band and who were famous but also completely unknown. Many years removed from superstardom, they would never be cool again, but also, they were never cool to begin with. They would never have another smash hit, but they had two more than nearly every other band in the history of history. They dropped from a major label to a very niche indie who specialized in Prog and Metal, which meant smaller budgets but also a bigger slice of the pie. And so, by the dawn of the new millennium, Kansas existed somewhere between total liberation and complete decimation.

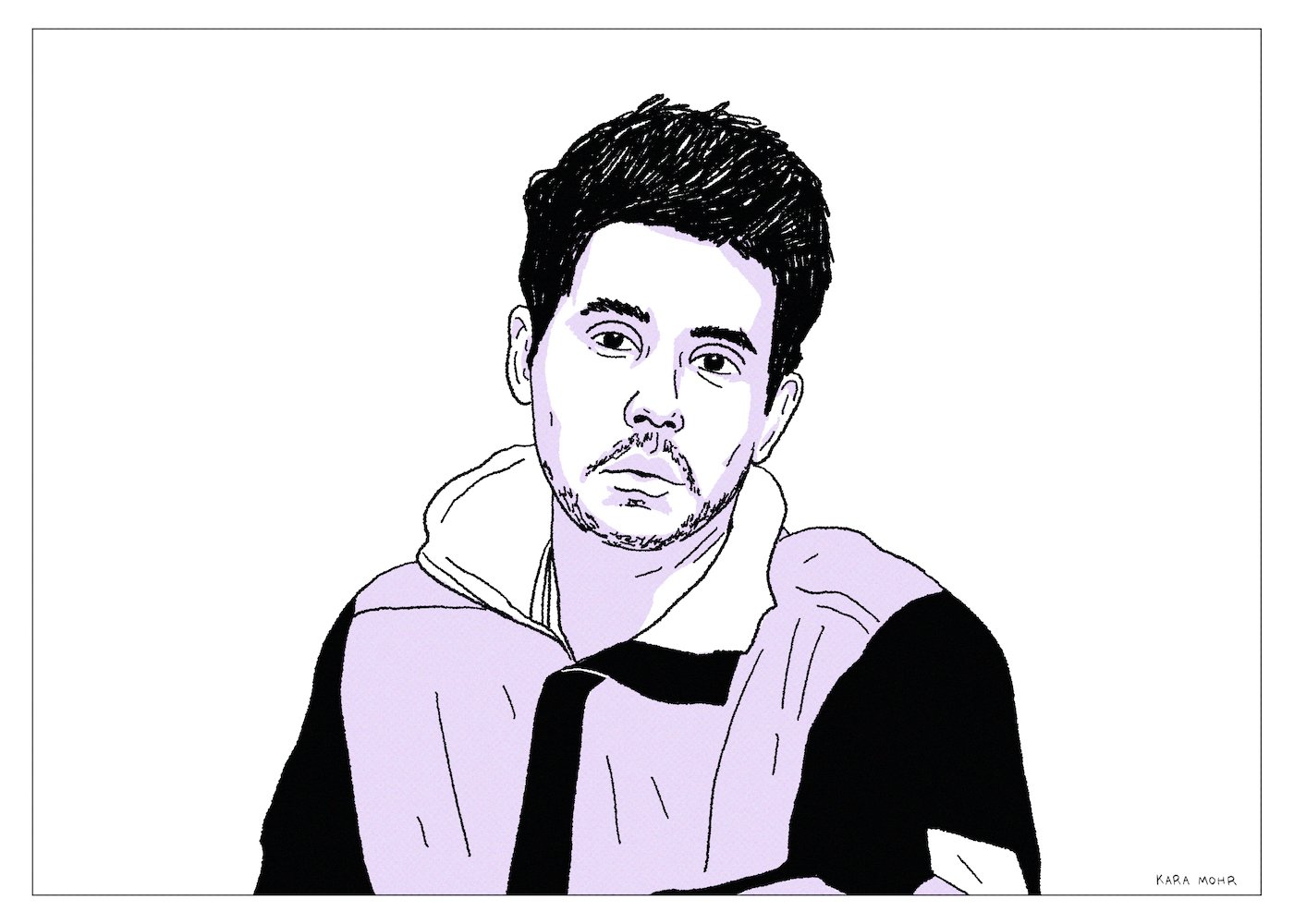

John Mayer “The Search for Everything”

Between “amazing” and “insufferable” — that’s the line Mayer walks. He is preternaturally gifted — as a player, he rivals his heroes, Robert Cray and Eric Clapton. As a composer, his mastery extends far beyond his ostensible peers — Maroon 5, Jack Johnson and Jason Mraz. He has always been tall, dark and handsome. He’s always been a great interview — frequently too great. But it’s the speed and intensity of his amazingness, that unnerves. Going from Jennifer Love Hewitt to Jessica Simpson to Minka Kelly to Jennifer Anniston to Taylor Swift to Katy Perry in close succession. Hanging with Dave Chapelle one night and jamming with Bob Weir the next night. Or, the same night. Swapping Nikes for Uggs. Wearing shades that are more expensive than his already expensive shoes, and watches that are tenfold the cost of either. It’s all amazing. And it’s all insufferable. And, believe me, John Mayer knows it.

Jack White “Entering Heaven Alive”

Willy Wonka succeeded because he was more fun than he was weird — which is saying a lot because he’s really fucking weird. But the older Jack White got, the less we could detect the humor in his Wonka-ness. Where there was once “Sugar Never Tasted So Good” and “We’re Gonna Be Friends” there was now dystopian Nashville, Steampunk Blues and Art with a capital “A.” To be clear, I have absolutely nothing against any one of those things. But stripped of its wide-eyed delight, White’s music began to veer from strangely astounding into the realm of astoundingly strange.

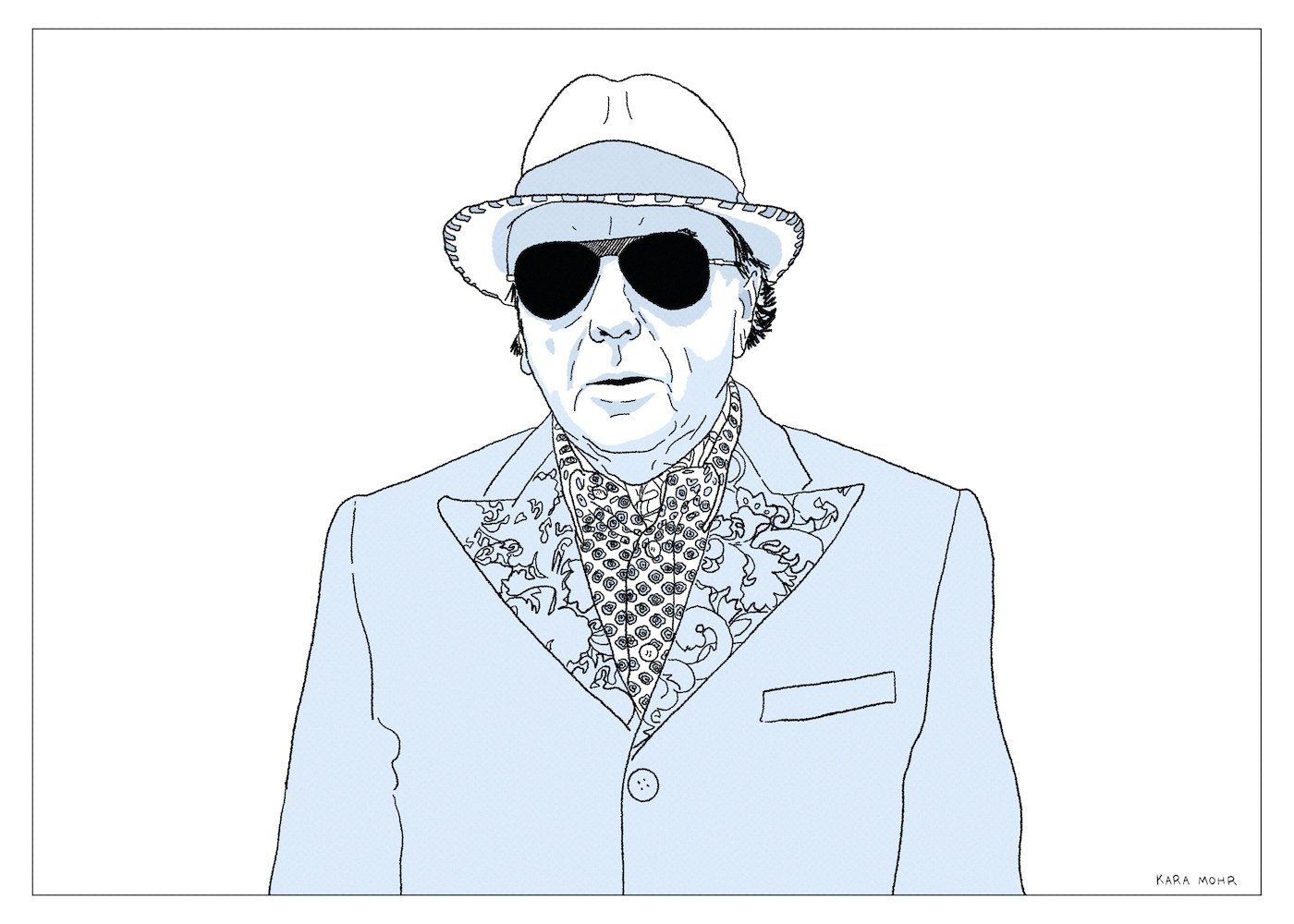

Van Morrison “What’s It Gonna Take?”

“Somebody said it was about the data.” It’s just one, of many, unimaginable lines from “What’s It Gonna Take?” There are other stranger lyrics on this album. Angrier couplets. Sadder admissions. But it’s the way he sings that last word — “Day-Tah.” Sharp consonants. Accent on both syllables. It’s not simply that I could not connect the guy who had spent decades searching for the mystic to this much older guy searching for statistical confidence. It was also the precision of his enunciation. The greatest singing mumbler, growler, la la la-ler I have ever heard was legendary for how he almost never enunciated — how he was more interested in sound and feel than in the words themselves. But with that single line, it became obvious to me that something was off. Very off. That a switch had flipped. And while I feared the worst for the rest of the album, I clung the thinnest strand of good faith. I hoped and prayed that there were other, plausible explanations for the Day-Tah.

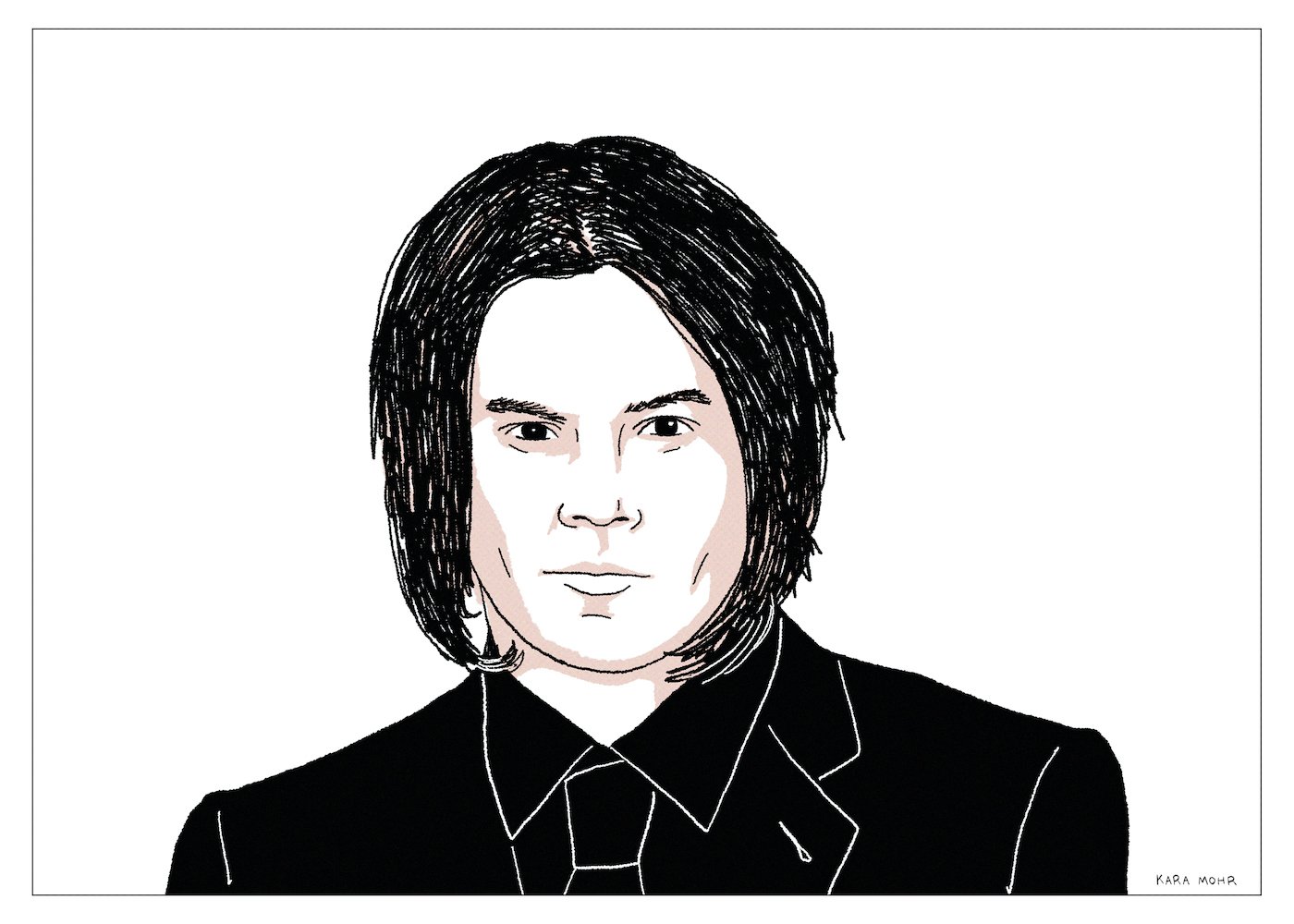

Thurston Moore “Demolished Thoughts”

More than any American Indie band from the Eighties, it is Sonic Youth who cast the brightest light and deepest shadow. Kim, Thurston, Lee and Steve broke rules and made albums of consequence. They were anti-establishment, even when they became the establishment. And they were groundbreakers in spite of their traditionalism — four pieces, two guitarists, one bassist, one drummer. But, as much as for their music, Sonic Youth was important because of Thurston and Kim — how they looked, how they acted and, most of all, what they signified about marriage and partnership. For every person who’d actually listened to “Daydream Nation” or “Sister,” there were dozens more who knew about Kim and Thurston. And every one of them knew intuitively — and with great certainty — that they were a marital ideal. Until they weren’t.