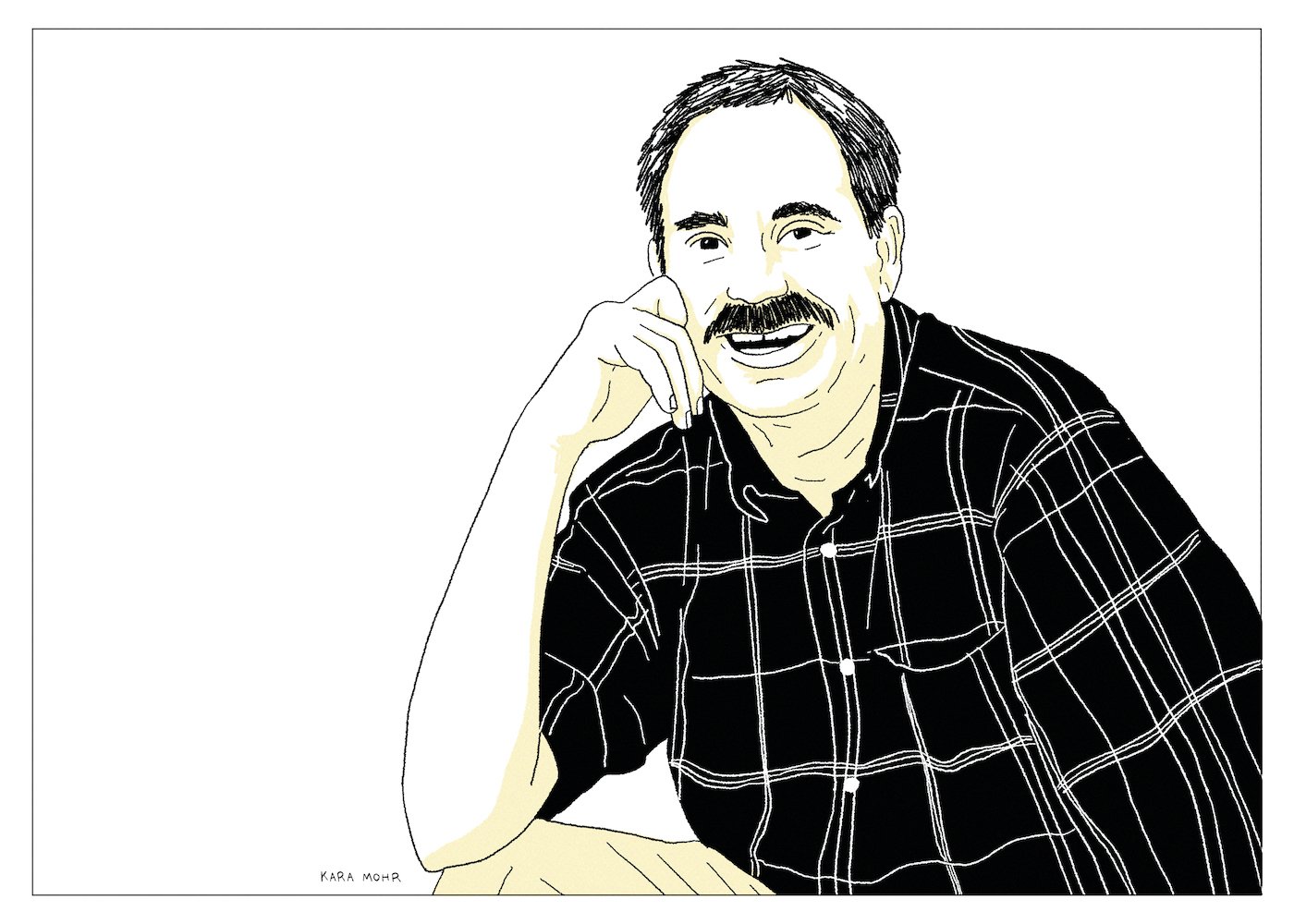

Dan Quisenberry “Poetic Relief”

Quiz was in no way physically exceptional. He looked the opposite of imposing, like somebody who spent more time reading than working out. His hair was brownish red and thinning up front. And his mustache was thick, wide and furry. Frankly, it was adorable. Whereas Rollie Fingers’ stache was a cursive distraction and Goose Gossage’s was pure intimidation, Dan Quisenberry’s mustache looked like the fourth member of Alvin and The Chipmunks. He couldn’t hit ninety on the radar gun. And he wrote poetry on the side. No matter how out of place he seemed in his Royals’ uniform, though, it was nothing compared to his delivery. The “submarine pitch” had been around for most of baseball’s history, but nobody threw it quite like Dan Quisenberry. He’d drag the fingernails on his right hand near the ground while hurling his right foot two yards towards third base and hopping his left foot two feet from the rubber so that he could somehow, miraculously, regain his balance. Meanwhile, the pitch would go down and then up and then down and to the left. It was nothing short of a miracle. All of it.

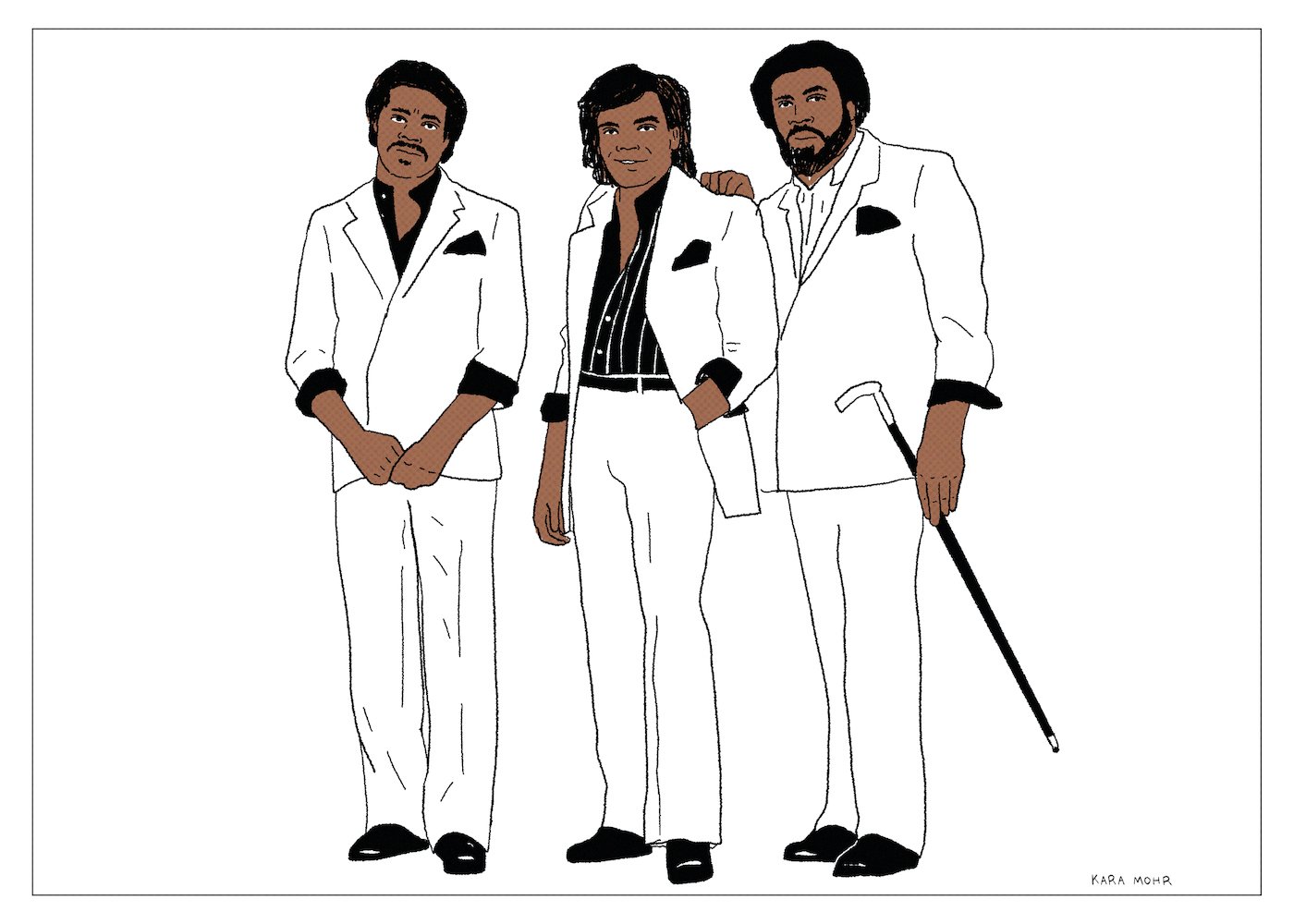

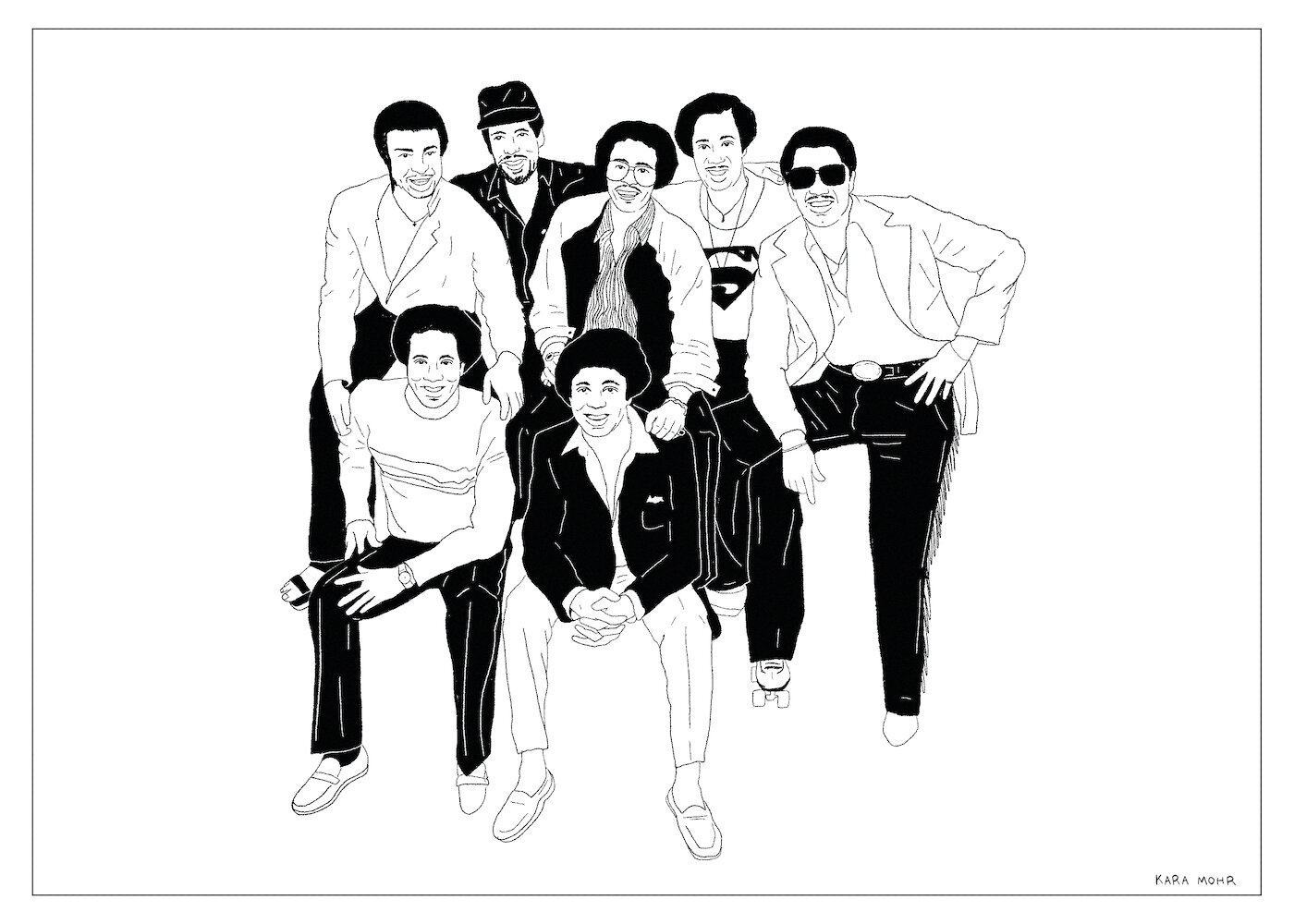

The Isley Brothers “Masterpiece”

In response to Marvin Gaye’s third act and to Luther Vandross’ debut, The Isley Brothers began to move away from Funk and Disco. “Between the Sheets,” from 1983, was a massively successful turn to the bedroom, but also the last album to feature all six Isley Brothers (counting in-law, Chris Jasper). Mounting debt and creative tension ultimately led to the departure of the younger trio, leaving the middle-aged brothers to carry on. Without Ernie’s electric guitar or Chris’ writing and arrangements, however, change was inevitable. Their eventual pivot, entitled “Masterpiece” and released in 1985, featured the three senior Isleys on the cover wearing tuxedos. Ron is seated on a red velvet and gilded chair that looks a lot like a throne. Rudy is standing stage left, holding a regal walking stick. Eldest brother, Kelly, is stage right, mustached and assured, even as he approached sixty and was beginning a battle with cancer. The title and the cover of “Masterpiece” said precisely what they needed to say: classy, but still a little horny.

Steve Winwood “Roll With It”

In the second half of the 1980s, while we were happy to have luxury sedans in our garages and gas at the pump, there was still a sense of longing. Was it for JFK? MLK? The counterculture? Whatever the cause, our collective ennui — even as the economy boomed and the Cold War thawed — was unmistakable. We knew it, but we couldn’t place it. And so, we had questions. Fortunately for us, Bono had answers. So did Phil Collins and Sting and Bruce and Neil and, surprisingly, Don Henley. Our beloved Amnesty rockers, celebrated in the pages of Rolling Stone, sang with purpose. All of them, except for Steve Winwood, who opted for New Wave, Blues Brothers fare and farming in The Cotswolds. While his esteemed peers were consumed with importance, the most talented member of the bunch quite literally told us to roll with it.

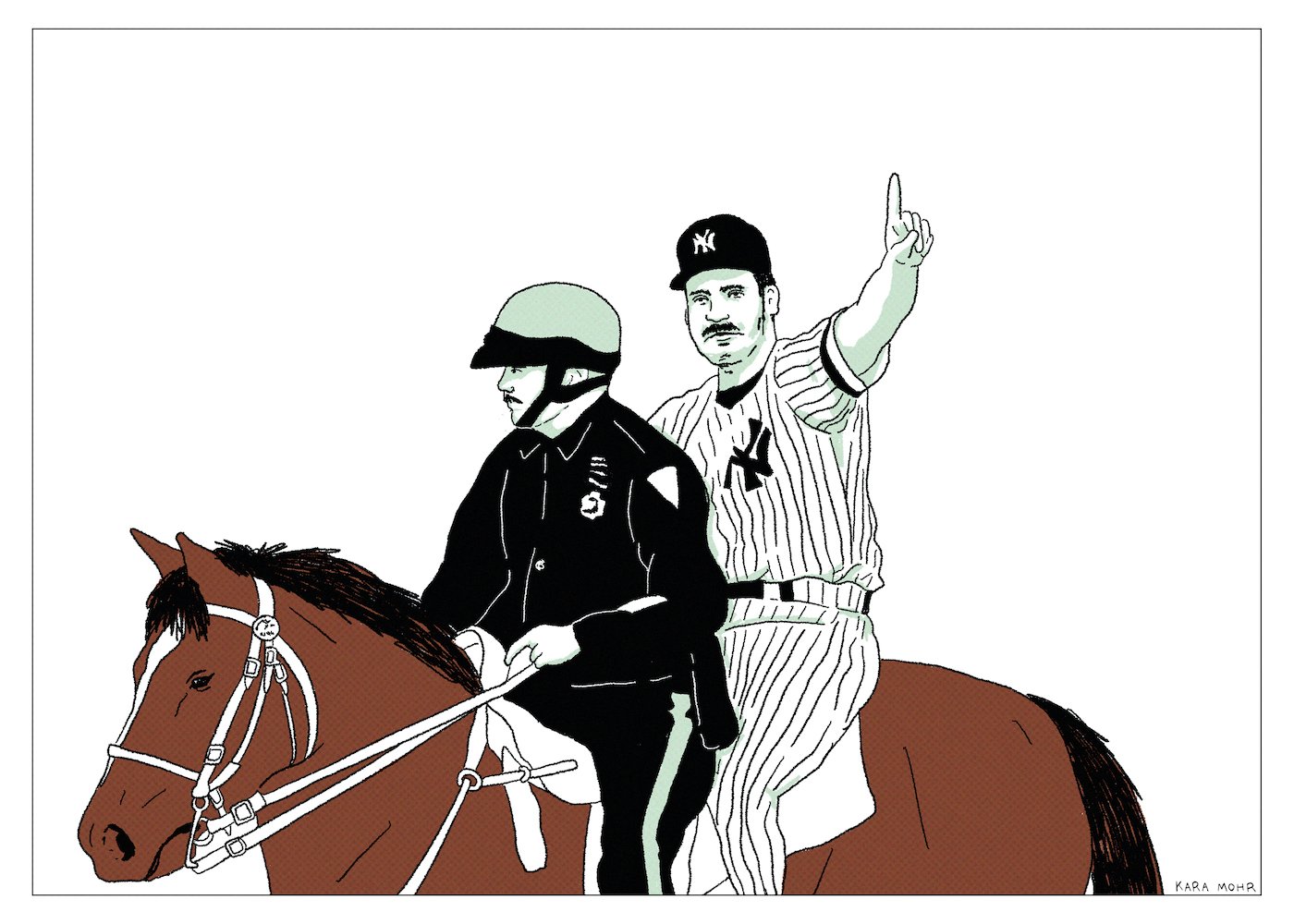

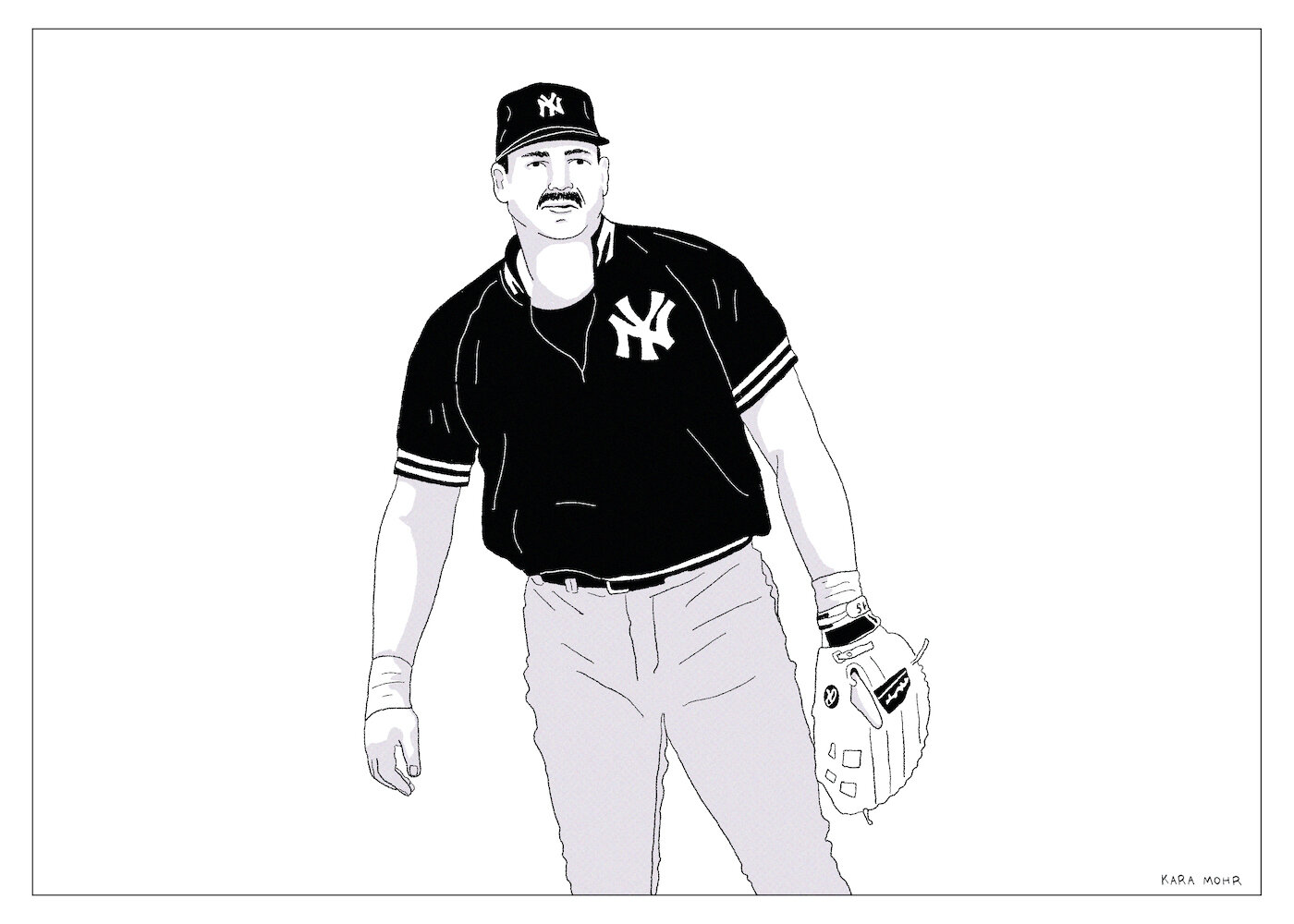

Wade Boggs “The Visible Man”

Wade Boggs told the world many stories. That he twice saved his own life by turning invisible. That he once drank 107 beers on a cross-country flight. That his baseball hitting prowess was aided by poultry consumption. That he was a New York Yankee. But, what was the truth? Was he delusional? Was he magical? Was he just a neurotic with astounding hand-eye coordination? One thing is certain: it must have been hard work to become Wade Boggs. Willie Mays and Joe DiMaggio were beloved for making baseball look so easy. Wade Boggs, on the other hand, had to hit Dave Stieb sliders and check his watch to see if he could end practice on a 7 and trace Hebrew good luck charms in the dirt and find missing pennies in the dirt near The Green Monster. He did that, every game of every year, while also hitting .330.

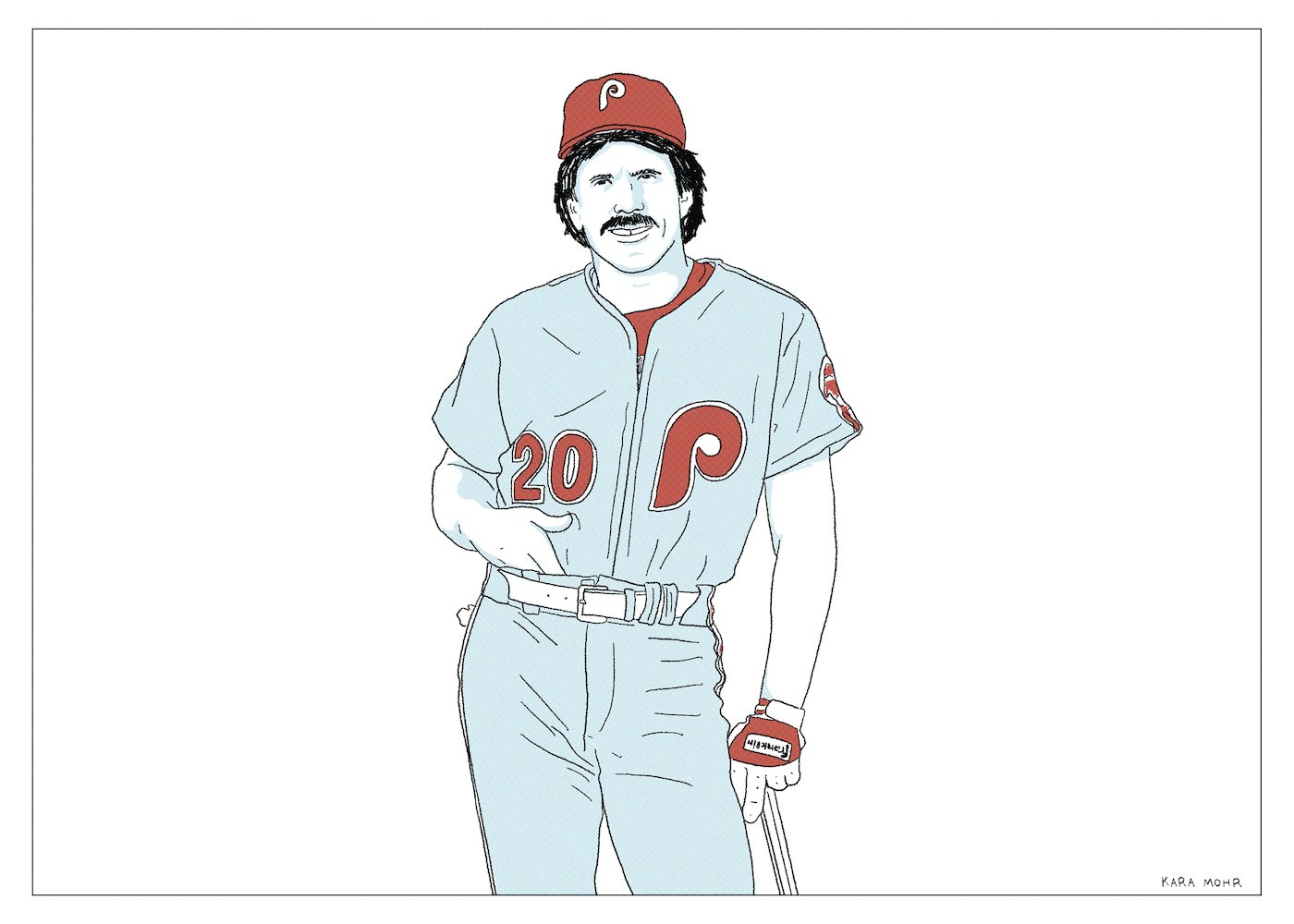

Mike Schmidt “Two Very Bad Knees and a Dream”

Pete Rose was filthy. George Brett had hemorrhoids and a temper. Willie Stargell had a massive gut. Dave Parker and Keith Hernandez smoked in the dugout. Rickey Henderson was from another planet. Half the league was popping pills. And the other half was coked out. The joy of Willie Mays was replaced by the swagger of Reggie Jackson. The 1970s was a decade of lost innocence for major league baseball. The 1980s were perhaps weirder still. What had been a relatively staid game from 1920 through most of the 1960s was suddenly less predictable. In fact, it was becoming downright bizarre. Change was everywhere. Except, of course, at third base in Philadelphia, where Michael Jack Schmidt stood, permed and mustached, for nearly two decades.

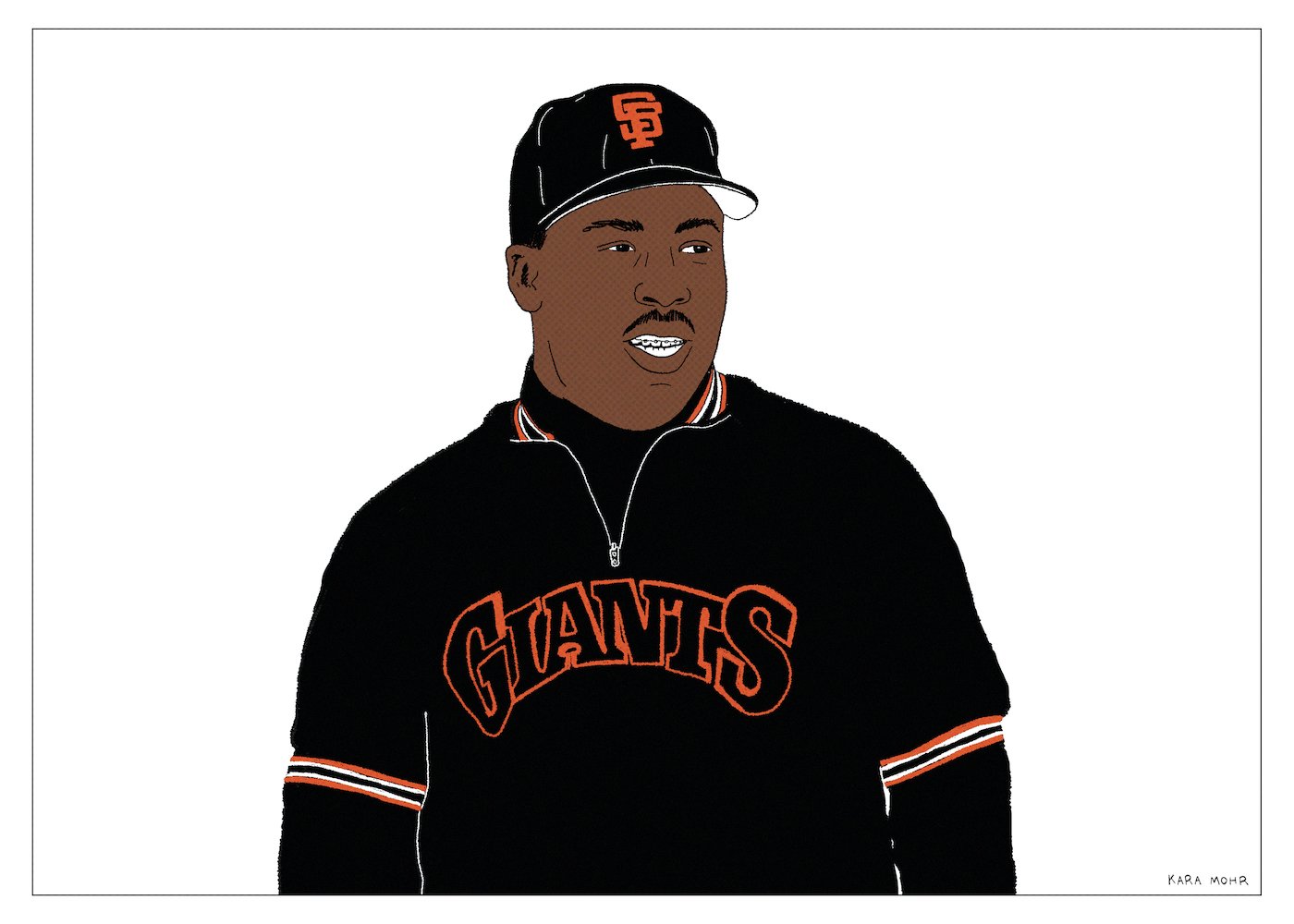

Kevin Mitchell “All In”

Moments after The Clintons entered our lives, but right before PEDs consumed baseball, Kevin Mitchell was chasing immortality. By the All-Star Game, he was ahead of Babe Ruth’s home run pace. One night in April of 1989, he chased down a tailing Ozzie Smith line drive and caught it between the foul line and the wall — barehanded! Though I was not old enough to have seen Maris’ run at Ruth or Reggie’s run at Maris, I knew greatness when I saw it; even if it was sudden and unexpected and from a guy who was recently the fifteenth best player on the Mets. So, I responded in a way that felt beyond obvious to my eleven year old self: I emptied my non-existent bank account, forced my Dad to take me to the nearest baseball card convention and began to corner the market on Mitchell rookies. I was all in.

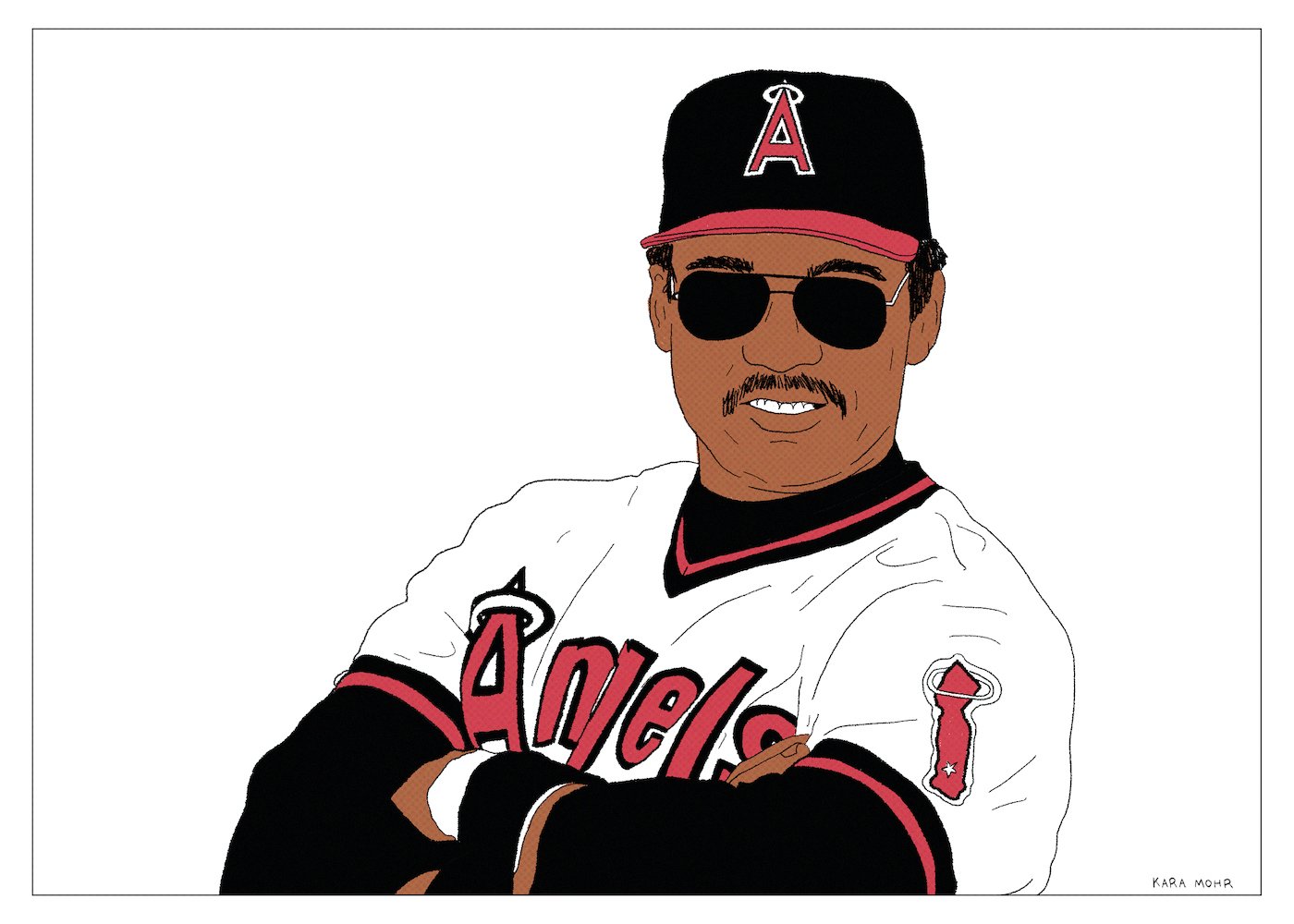

Reggie Jackson “Old Reggie”

In 1988, Reggie Jackson co-starred in “The Naked Gun,” where he attempted to assassinate Queen Elizabeth, only to be foiled by Enrico Palazzo. For younger generations, it is that Reggie — older, sillier, wearing prescription sunglasses — who they remember. But, not me. I was too young to remember Reggie, the young Oakland phenom. And I barely recall the magic of 1977. My Reggie was the superstar on a candy bar wrapper. At the plate, he appeared menacing and unpredictable — but still like a man. He wasn’t a bull, like Greg Luzinski, or a viking, like Gorman Thomas. Reggie just looked like a guy who wanted it way more. Who swung with more violence. Who tried harder. And who made it very easy to see how very hard it was to hit five hundred and sixty three home runs.

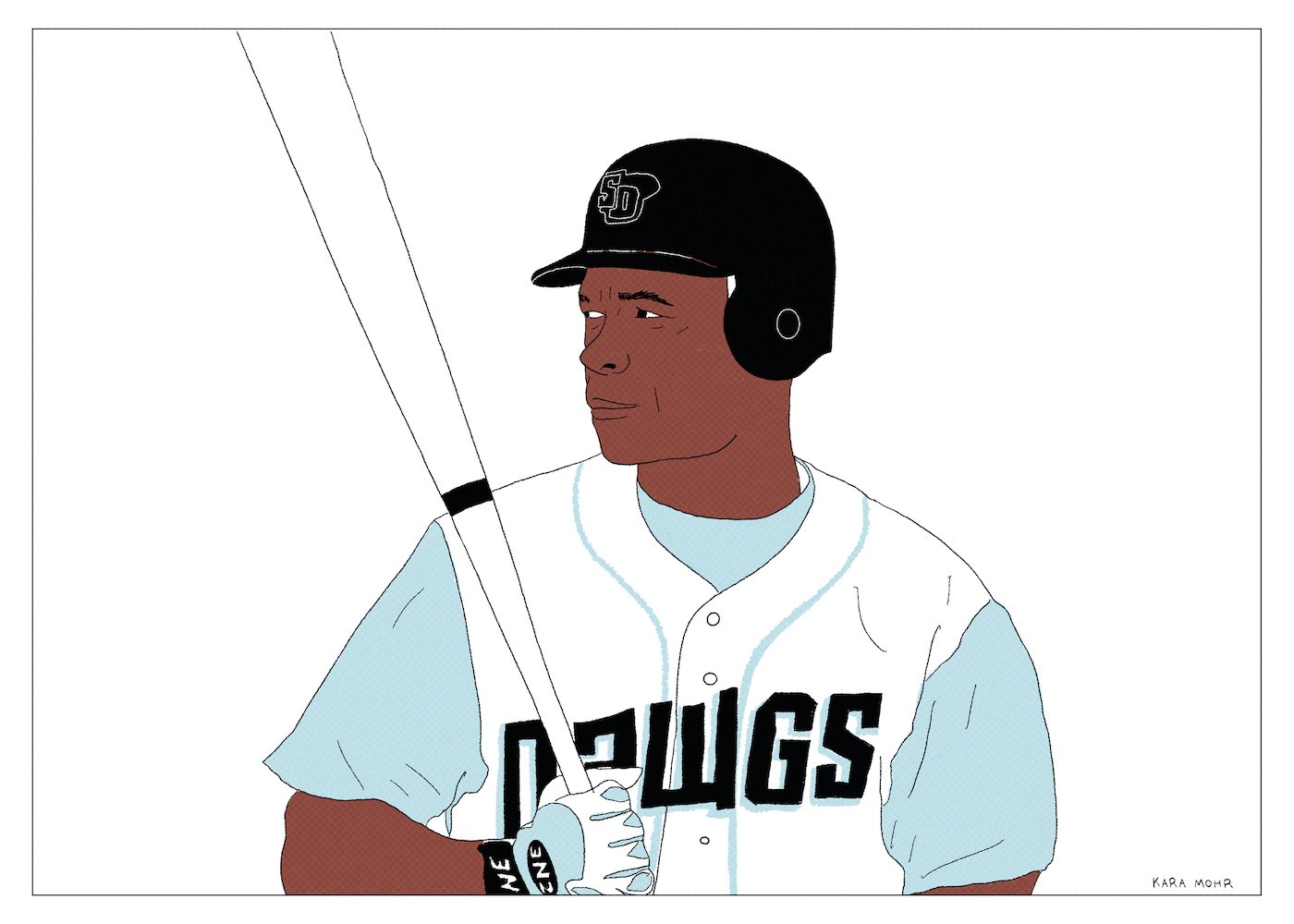

Rickey Henderson “The Greatest of All Time”

People (like me) lazily toss around adjectives like “incomparable” or “singular.” But there has never been a person so professionally atypical as Rickey Henderson. He made Steve Jobs and Henry Ford seem kind of average. He had more in common with Hermes or Spiderman than with Vince Coleman or Mookie Wilson. And, for twenty five seasons, he broke major league baseball. He wanted to play forever. He was certain that he could. But, in 2005, he was a San Diego Surf Dawg of the Golden Baseball League — where young men who will never make the Big Show went for a summer of fun and where former pros were put out to pasture.

Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker “Keystone Kids”

Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker played nearly two thousand major league games together, turning over a thousand double plays between shortstop and second base. Trammell is in the Hall of Fame and Whitaker — based both on the data and Trammell’s impassioned case — should probably be there as well. They bunked together in the Minors, arrived to a suffering franchise in 1978 and, eventually, delivered the Tigers a World Series title in 1984. They are each other’s indisputable, number one fans. Forty years after they first played catch, the Keystone Kids have come to signify that elusive, romantic thing that men of a certain age rarely discuss but constantly long for: friendship.

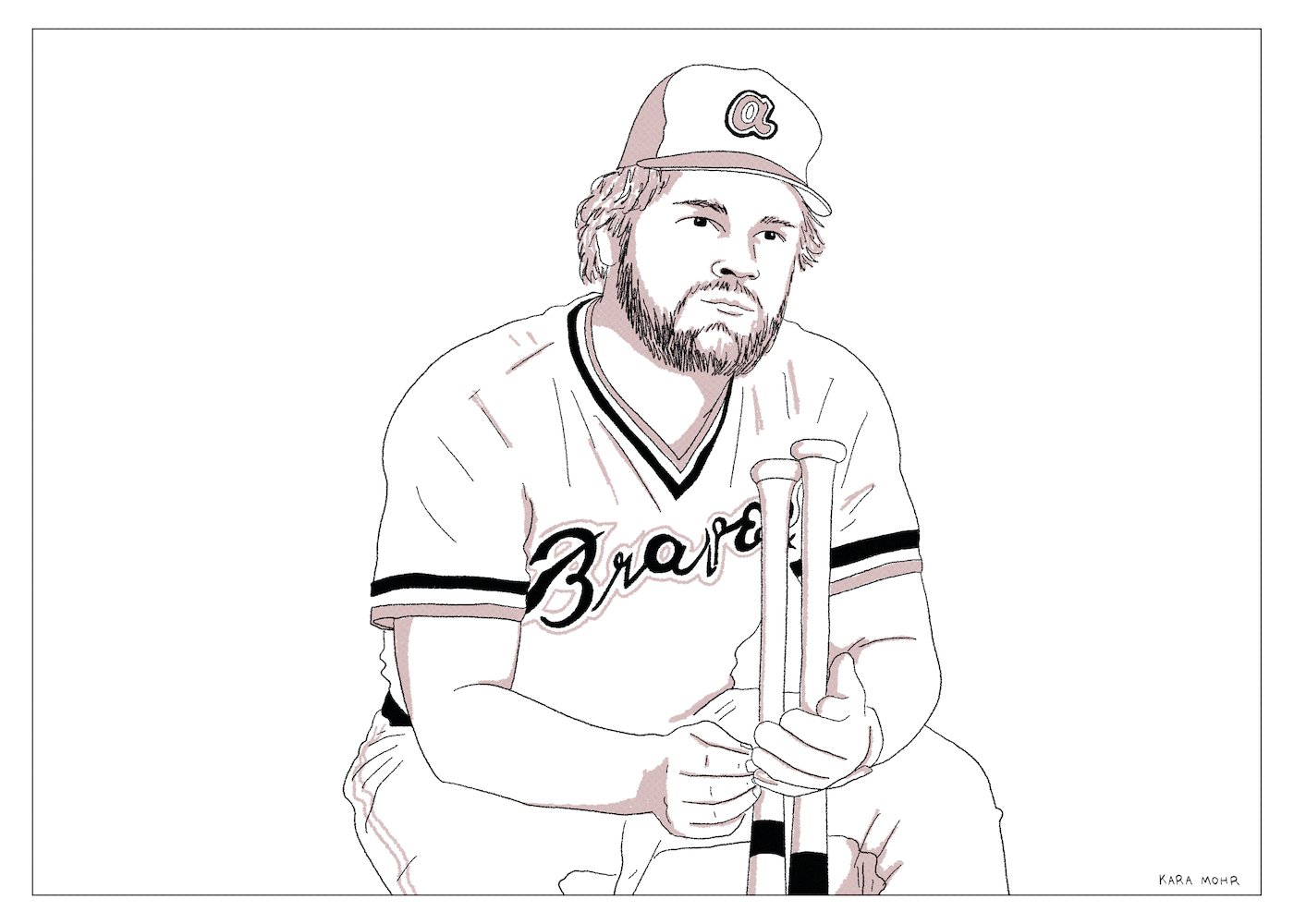

Bob Horner “Mr. Ho Mah”

Bob Horner never had career angst. He was born to use his hands and arms to strike objects with tremendous force. I suppose he could have been a great boxer, though that risks personal injury. Had he been born abroad, maybe he would be known today as the greatest cricket player of his generation. I guess he could have been the MVP of a building demolition outfit. Those were all possibilities. But when you’re born in Kansas in the late 1950s, and you look like the love child of Babe Ruth and Kenny Powers, there’s really only one job for you. It was unthinkable that he would do anything else with his life other than hit home runs and make terrible hair decisions.

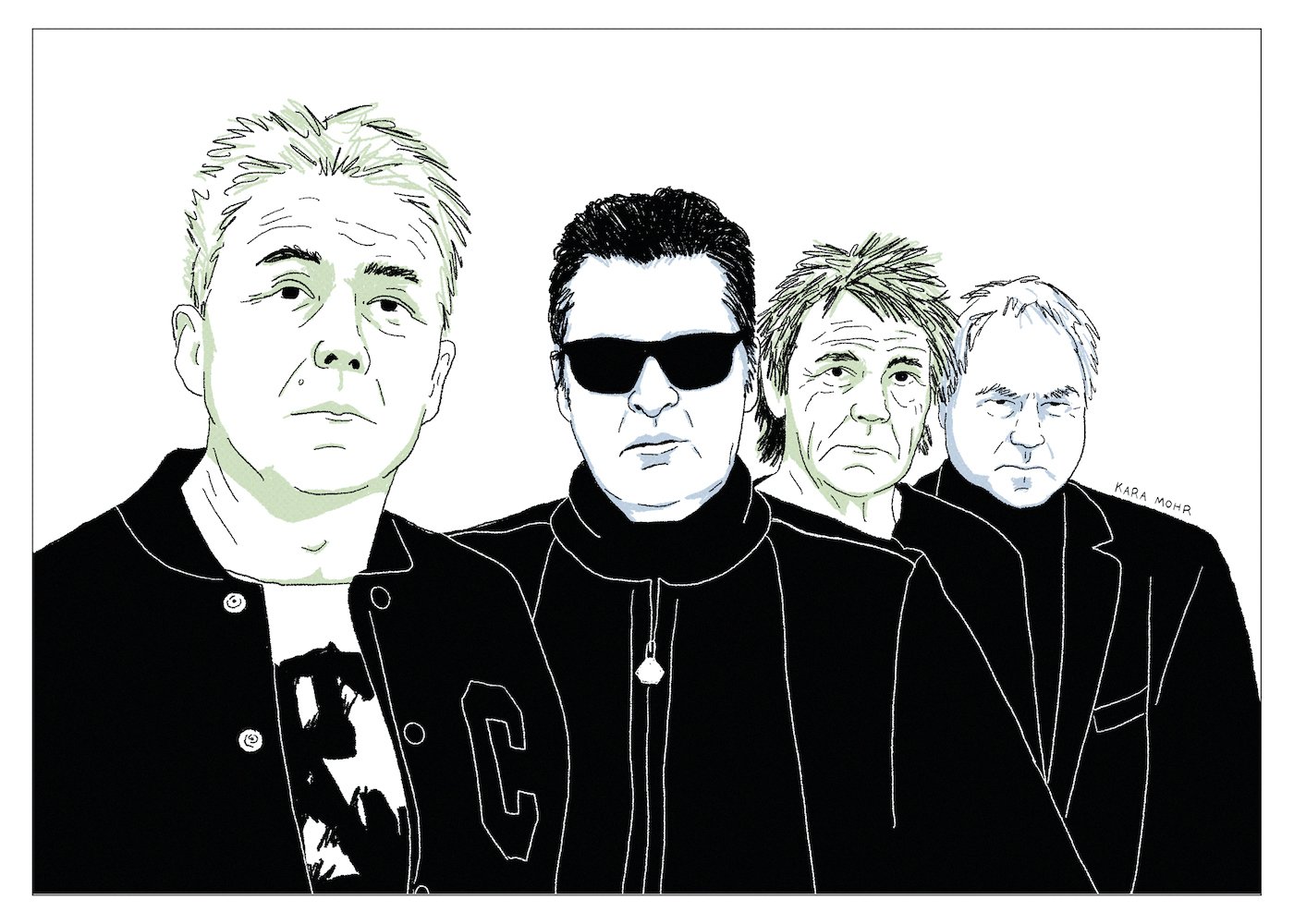

Golden Earring “Keeper of the Flame”

Rock and Roll is littered with one hit wonders and spectacular flame outs. But Golden Earring were neither of those things. They had two, massive hit singles, both of which have oddly endured as canon. Decades after their prime, they were still superstars at home, in The Benelux, where their faces adorned postage stamps. But, as far as I knew, they had disappeared around 1983, soon after “Twilight Zone,” the four minute MTV mystery that altered my young life. What happened? Where had they gone? It all had a whiff of semi-Nordic true crime. Information was scant, especially in The U.S., where Golden Earring were the coldest of cold case files.

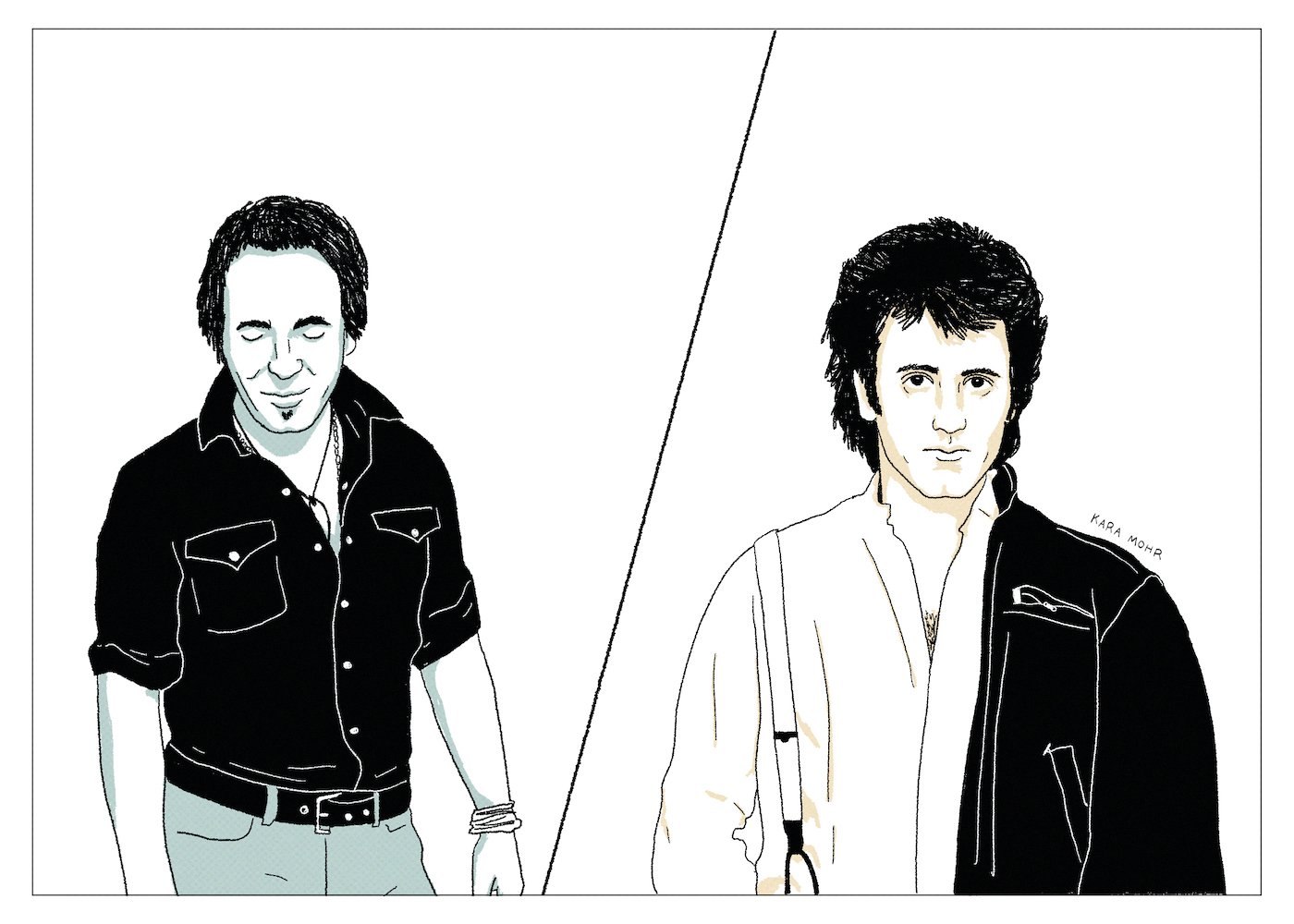

“Far From Over” (Frank Stallone) vs “All I’m Think’ About” (Bruce Springsteen)

In the early 70s, a million to one shot from the swamps of Jersey emerged as the “next Dylan.” Around that same time, less than a hundred miles away, a lesser known songwriter was fiddling with a keyboard, dreaming of the day that his older brother would include his music in the ultimate underdog movie. These two long shots, so near to each other but so completely divergent, demanded comparison. We pitted the nasal falsetto of Bruce Springsteen’s “All I’m Think’ About” from 2005 against Frank Stallone’s epic, 1983 Jazzercise jingle “Far From Over.” Who wins — The Boss phoning it in past his prime or the critically derided brother of Rocky during his graciously brief prime?

Steve Balboni “Bye Bye”

Steve Balboni’s body so exquisitely matches his surname that one would expect a rough Italian translation for Balboni to be “husky designated hitter.” Perhaps there is a village—maybe a small timber community in Northern Italy — where prosperous, mustachioed Balbonis have swung felled trees since time immemorial. Plus, to a seven-year-old in 1985, the name sounded a lot like a combination of Baloney and Bambino — which, frankly, just made sense. As a child, it was unspeakably obvious what “Balboni” signified. Today, as a grown man, it is almost frighteningly unclear.

Waylon Jennings “A Man Called Hoss”

In 1987, off drugs, but stuck with a six pack a day habit, Waylon decided to make an “audio biography.” That lovable, but lightweight album was more like a Disney amusement park ride than the proper autobiography he would finally write ten years later. Taken together, though, they taught me what I needed to know about Waylon Jennings. That he wasn’t just an outlaw. Wasn’t just the guy who played bass for Buddy Holly. Wasn’t just a Highwayman. He was all those things. But, most of all, he was the guy with the perfect Country voice who screwed it all up, so that he could make it all right again.

The Temptations “Reunion”

By 1982, The Temptations were more an aging institution than a Pop group. Motown’s solution was to bring back David Ruffin and Eddie Kendricks for a reunion and to pair them with the songs of Rick James and Smokey. At the time, Ruffin was addicted to crack and Kendricks voice was shot. Quickly and desperately, the seven Temptations assembled to record “Reunion,” an album that should have been an unmitigated disaster but somehow is weirdly delightful.

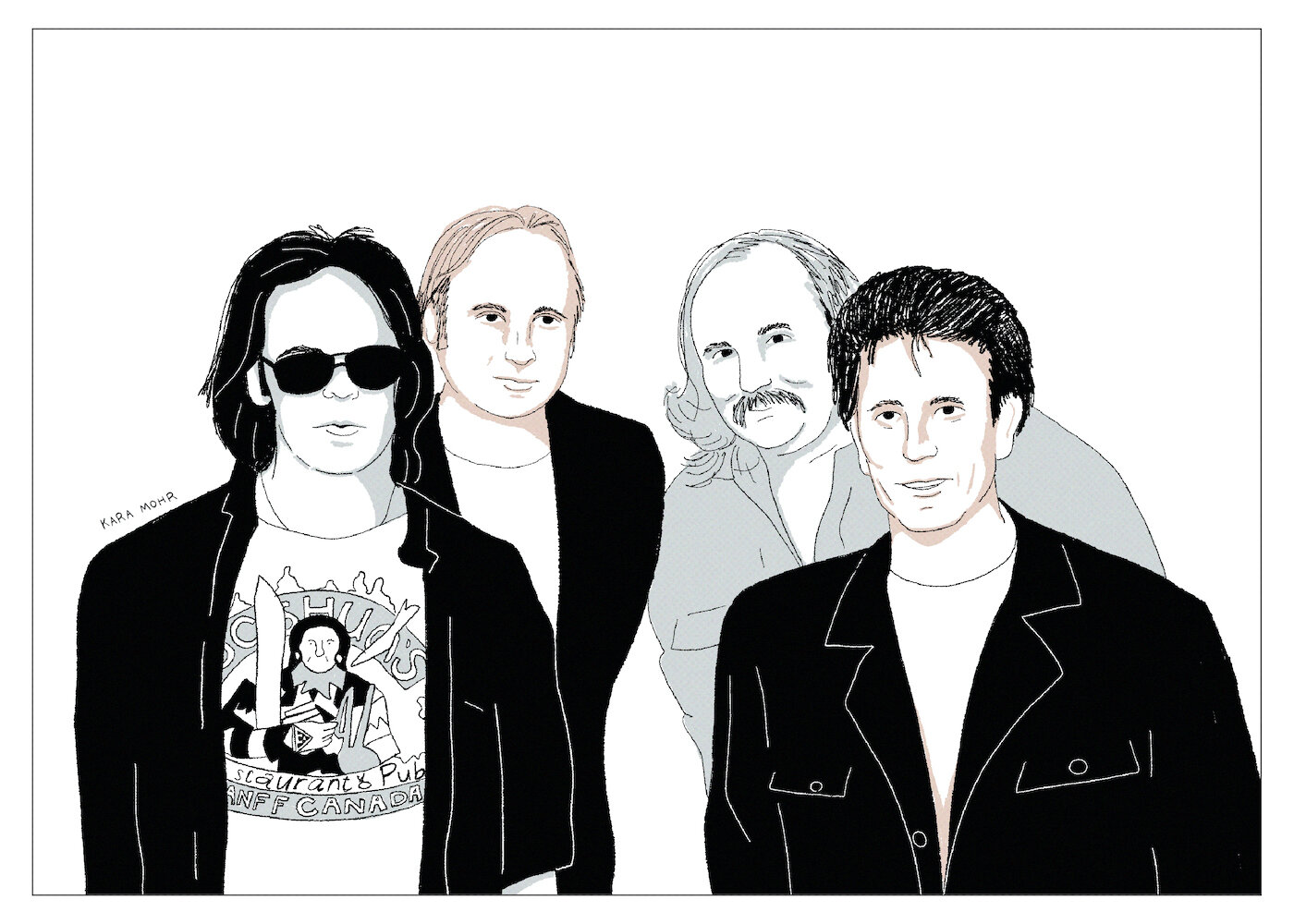

CSNY “American Dream”

CSNY arrived in 1969, at the very moment when the Hippie promise was at stake. Would their generation’s legacy be the end of Vietnam and the birth of Civil Rights? Or would it be Altamont, Manson and a two decade hangover? CSNY represented a generation holding its breathe before sunset. That sun finally set on November 1, 1988 with the release of “American Dream,” the long awaited, second studio album from Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

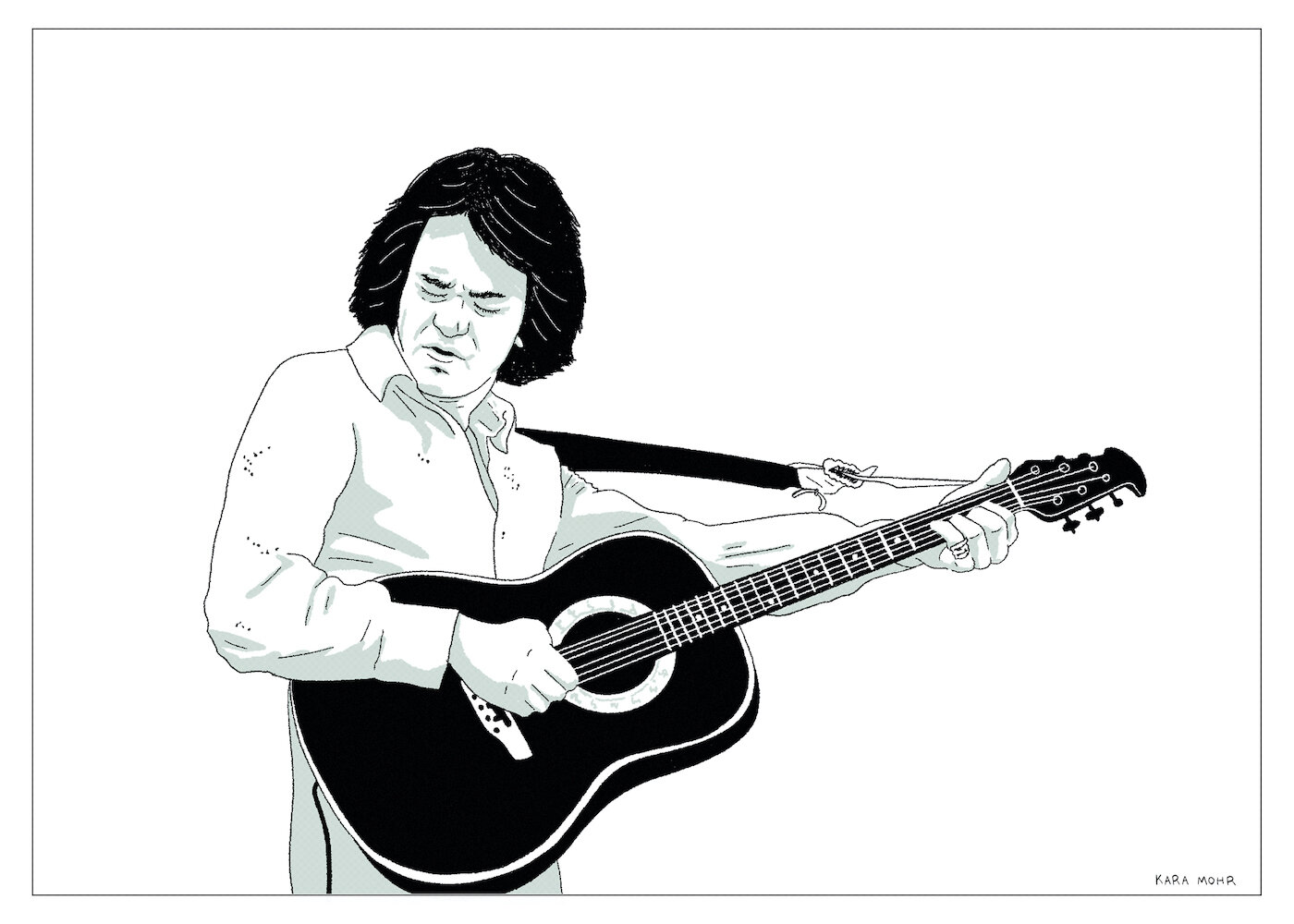

Neil Diamond “Heartlight”

Although it was not apparent at the time, Neil Diamond was on the verge of a slump as the 1980s approached. A sub-tectonic struggle was being waged between Neil Diamond, Contemporary Adult, and the emerging radio format known as “Adult Contemporary.” 1982, with the release of “Heartlight,” proved to be the year in which the movement swallowed its leader.

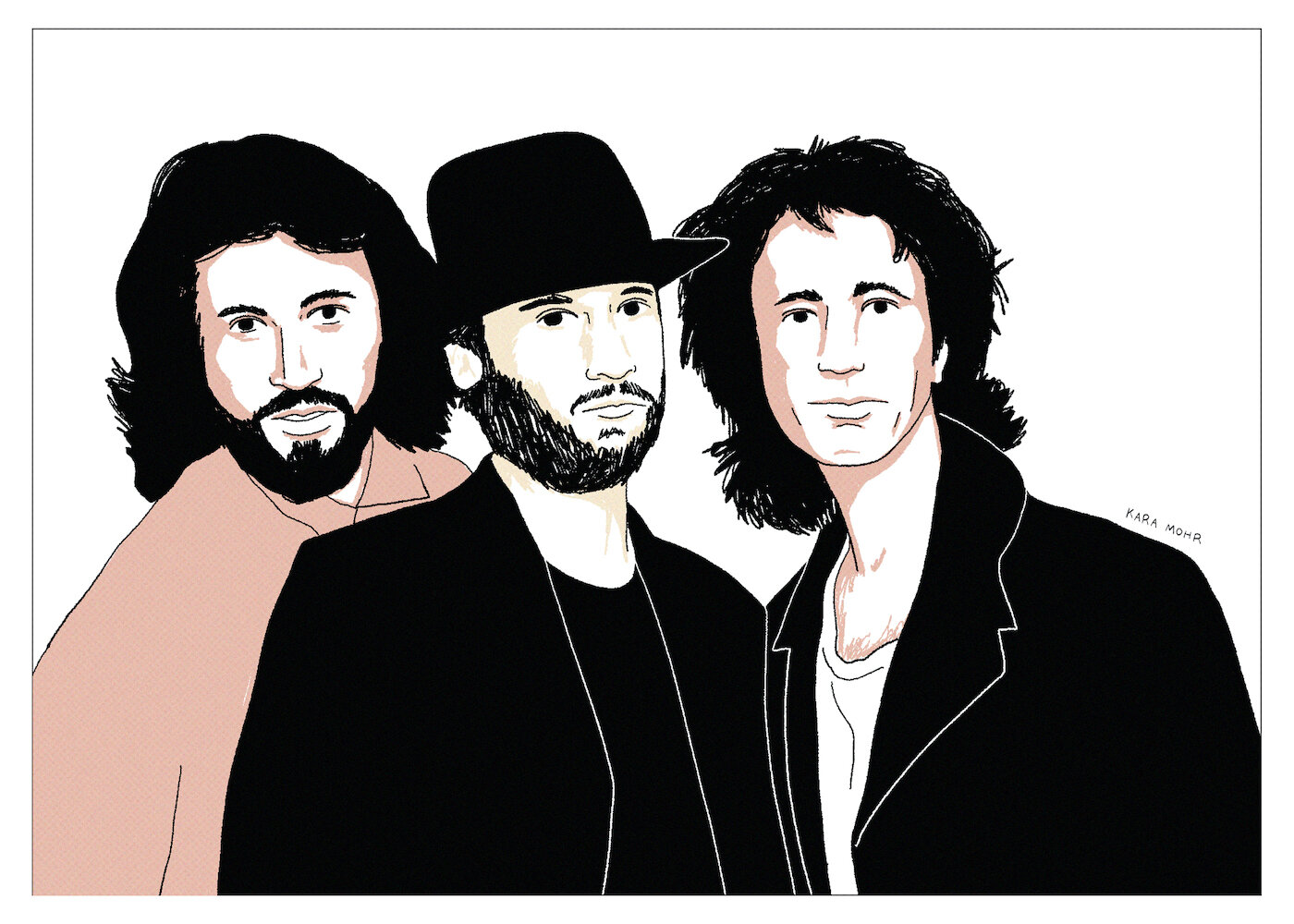

Bee Gees “E.S.P.”

In the mid-80s, having survived the disco revulsion on the wings of Barry Gibb’s songwriting for hire, the Bee Gees began work on a comeback album. However, the Gibbs were now on the cusp of middle-age. They had each grown up and grown apart. Barry turned forty in 1986. His once luxuriant mane had receded. Robin fixed his teeth. Maurice went to rehab. Amid the struggle of revisiting old muscles and older wounds, the band released “E.S.P.” in 1987, their first full length album in six years.

The Kinks “Word of Mouth”

In my tweens, a casual Kinks fan then, I remember seeing the cassette for “Word of Mouth” floating around the bargain bins at the mall. The cover was ghastly, desperately insisting this original British Invasion band was as modern as Duran Duran. It had some Rauchenberg-esque pink lips on it, yellow swooshes — a pop art eyesore. “Word of Mouth” has been described as chasing trends and as containing production that sounds pinched and compressed, even by the 1980’s worst standards. Its songs have been called “forgettable.” Well, I dissent! The album did not have any musical problem, it had a marketing problem.

The Grateful Dead “In the Dark”

1987. The Hippies were all grown up. Their kids now wore the tie dye shirts with the bears and skulls. The Dead were an industry by this point, albeit one that showed signs of great decay. Their last studio album, seven years earlier, was unimaginably tepid. In 1986, forty-four year old Jerry Garcia fell into a medically induced coma, caused by his worsening addiction. However, a year later, the band released “In the Dark,” their penultimate studio album. It was the beginning of the final chapter of a book that would end in 1992, but what a dramatic and unlikely final chapter it was.