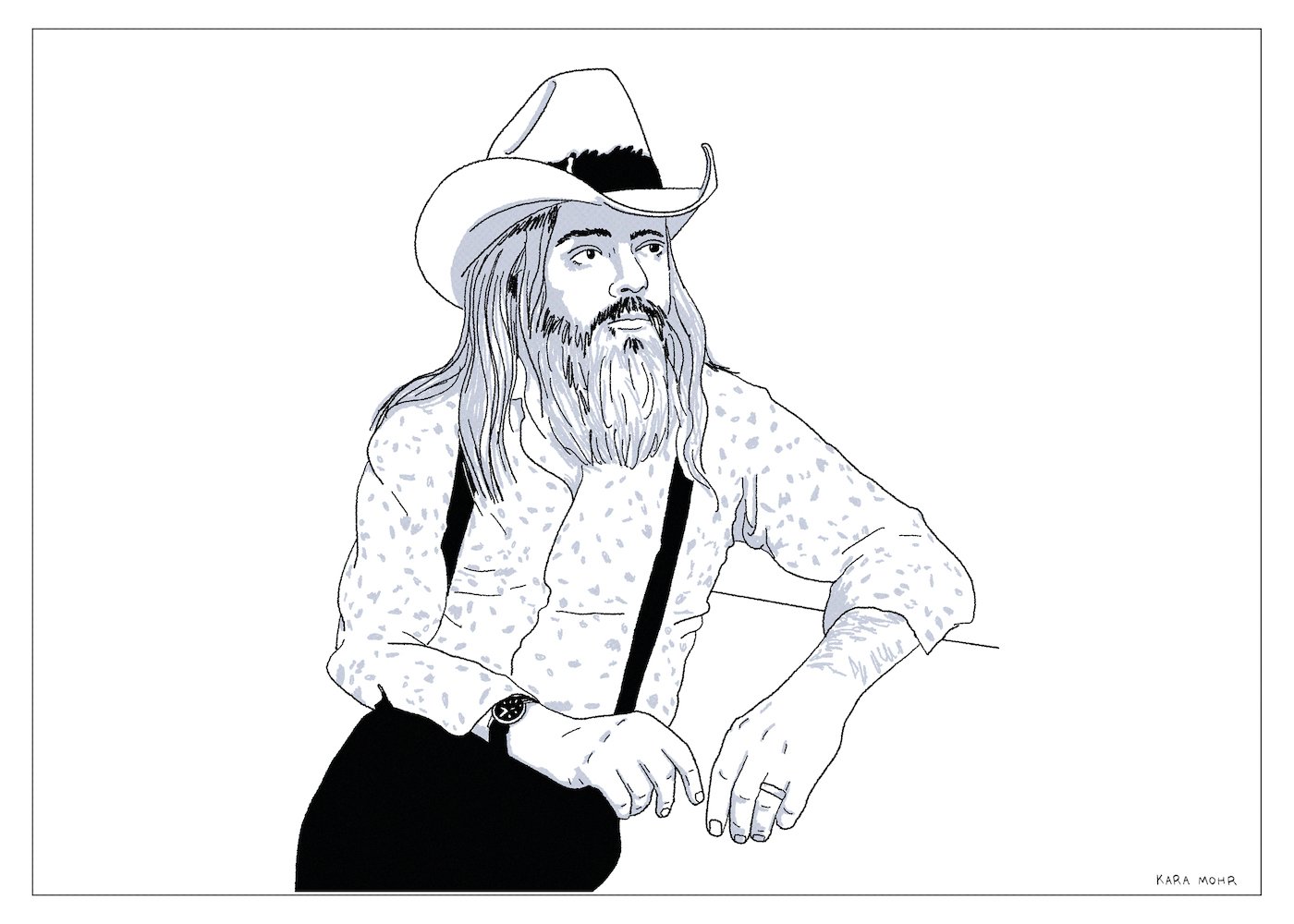

Leon Russell “Anything Can Happen”

Having spent more than a decade building his reputation as the “guy to call” when you needed a guy, Leon Russell was suddenly more than just “a guy.” He became “the guy.” In 1970, after touring with Delaney and Bonnie and releasing a critically adored solo debut, he put on his top hat, dusted off his beard and assembled the greatest live band on the planet for Joe Cocker’s “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” tour. And though the experience nearly killed him (and his bandmates), it marked the beginning of the next phase of his storied career. Whereas during the 1960s, Russell was on the side or behind the scenes, in the 1970s, he was a frontman, gracing album covers, standing center stage, and sharing the limelight with everyone from George Harrison to Willie Nelson. For a natural introvert who was perhaps meant to be a bandleader more than a Pop star, it proved to be too much for him. Depleted and lost, the man who’d released over a dozen albums in the Seventies, eked out only two the following decade. By the Nineties, he was stuck somewhere between the “where are you now” and the “who’s that guy” files. Leon Russell lost his way and then began to fade out, until, one day, Bruce Hornsby came a calling.

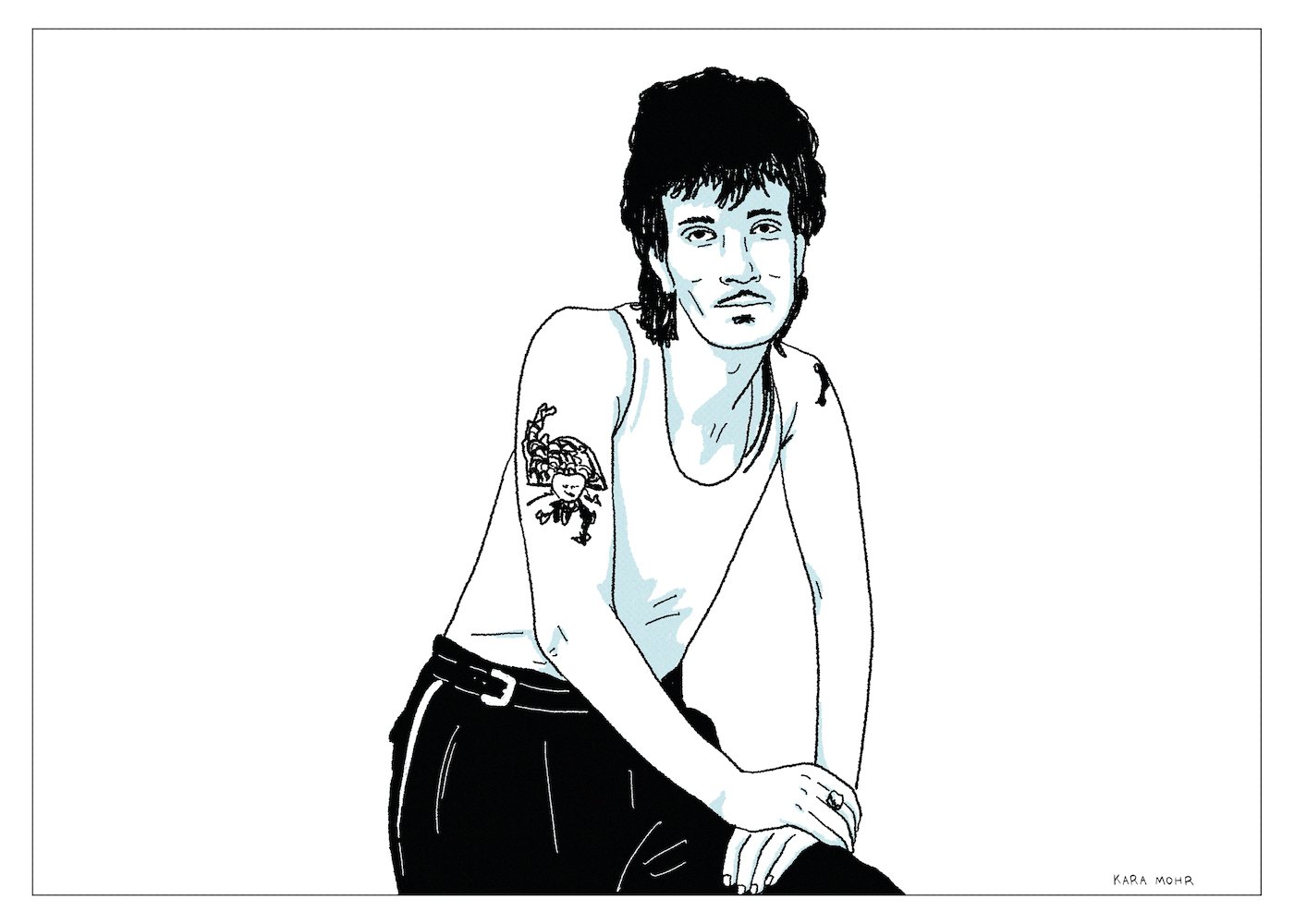

Willy DeVille “Backstreets of Desire”

When Dylan went from folkie hobo to poet in black turtleneck and shades, it seemed like affect. When Bowie went from Ziggy to Thin White Duke, it felt like an art project. And when Madonna went from Material Girl to S&M Barbarella, it came off like a marketing stunt. But Willy DeVille was the genuine article — a real life shapeshifter. The man born William Borsay Jr., from Stamford, Connecticut, would become a Spanish Harlem pimp, a Bowery gutter prince, a riverboat gambler, and a Navajo mystic. In 1992, somewhere between the Bayou and his eventual return to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, he briefly wound up in Los Angeles. And, in spite of crippling addiction and decades of commercial disappointments, Willy made one of the great, barely heard Roots Rock albums of the decade. “Backstreets of Desire” might read like something from Springsteen’s swamps of Jersey, but it sounds like the Los Angeles that made Los Lobos, Tom Waits and Warren Zevon.

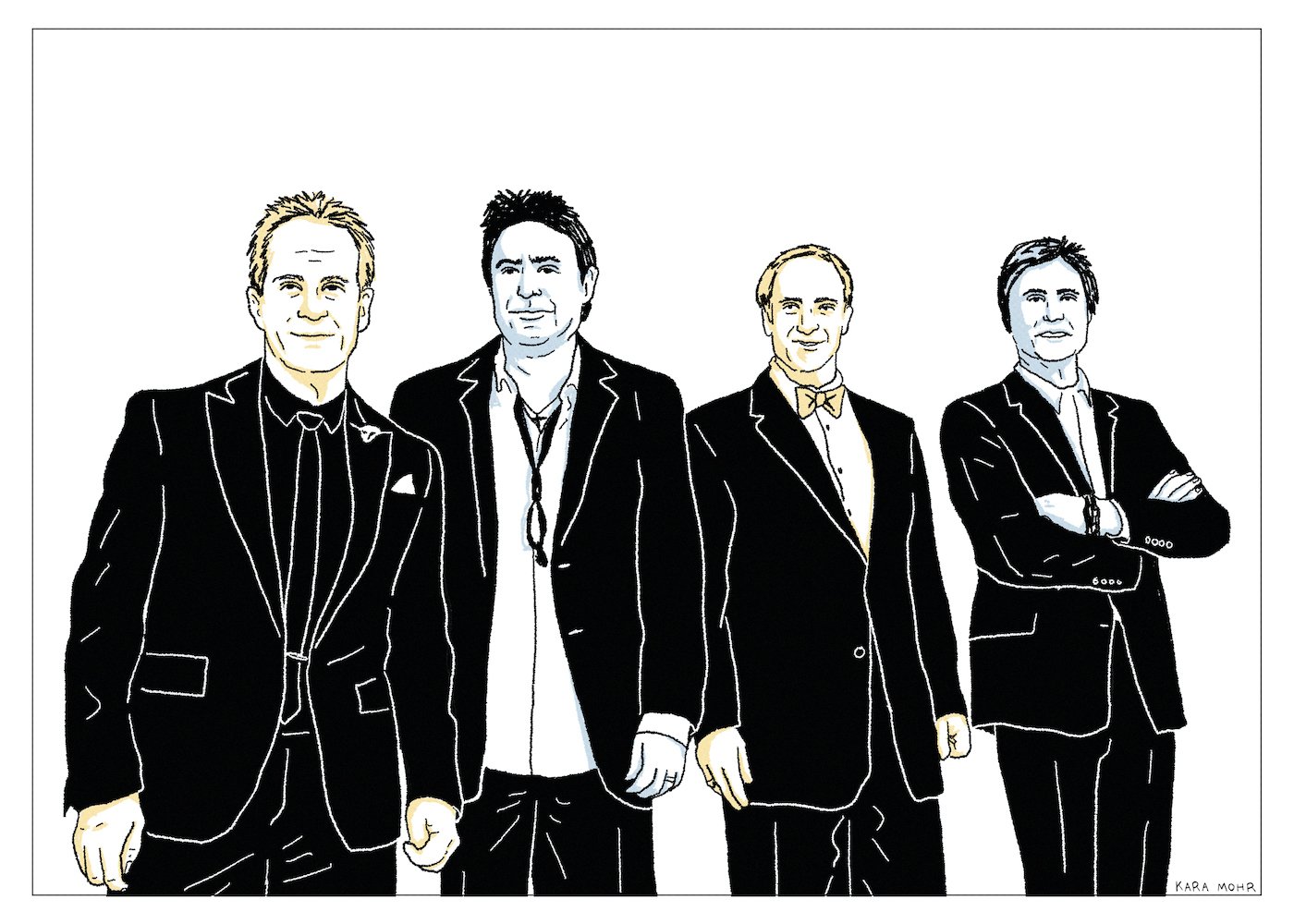

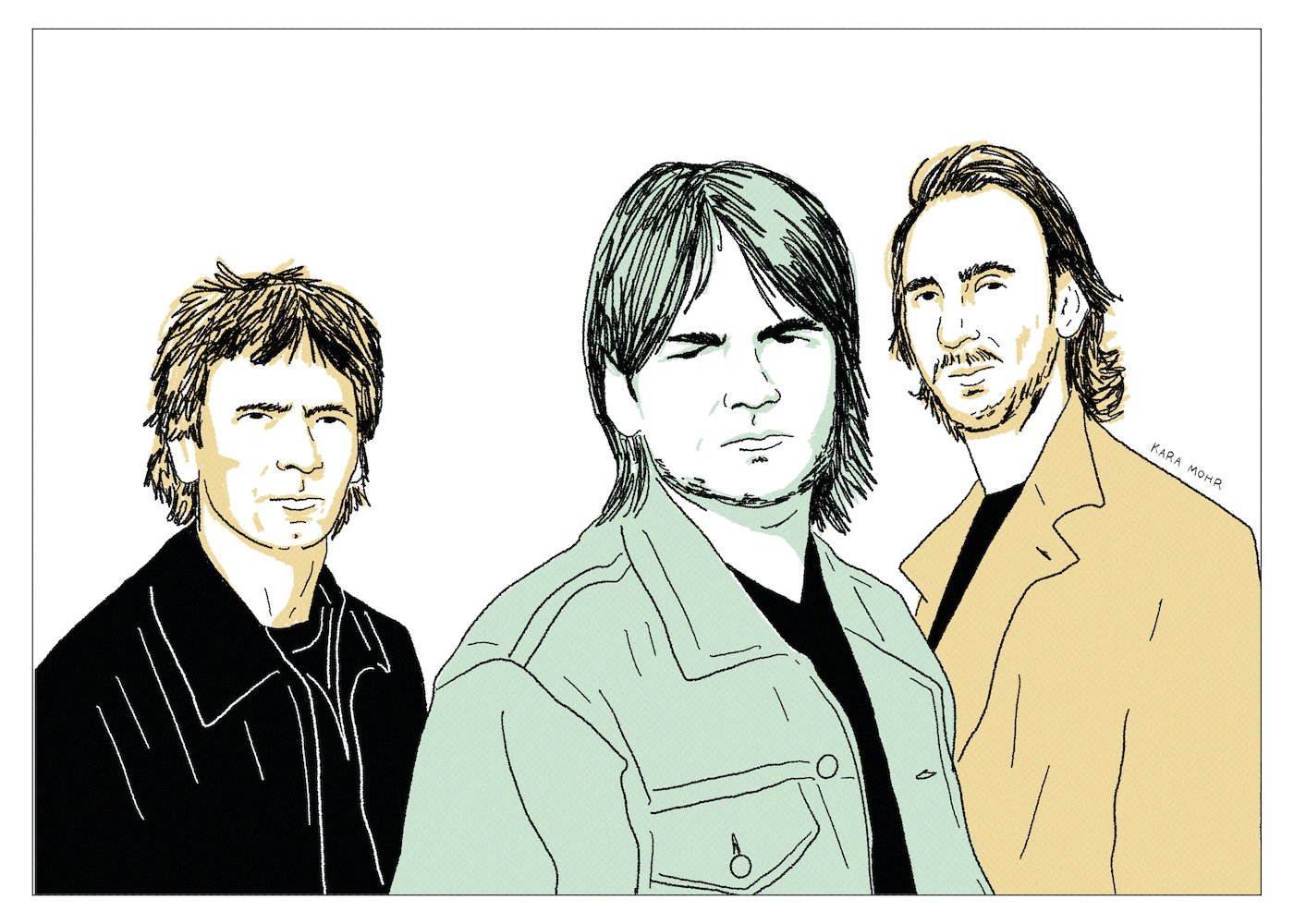

Cheap Trick “Cheap Trick”

The idea of a “return to form” is nothing new. Neil Young’s “Freedom” was his “return to form.” So was Clapton’s “Journeyman.” Dylan has probably “returned to form” half a dozen times in his career. The implication is the same: that some beloved, aging artist who had lost their way was finally making great music again -- music that confirmed their original brilliance. In 1997, ahead of their thirteenth studio album, writers and publicists were insisting that Cheap Trick’s latest was a return to form. Fans came out from the woodwork. Nirvana and Smashing Pumpkins and Weezer portended the event. Cheap Trick had found their way back. The band that Mike Damone and millions of Japanese teenagers once loved was coming back to get their due. But for a group whose success was so fast and so fleeting, and whose last hit was a hairy, ten year old power ballad, it was fair to wonder: what form were they returning to, exactly?

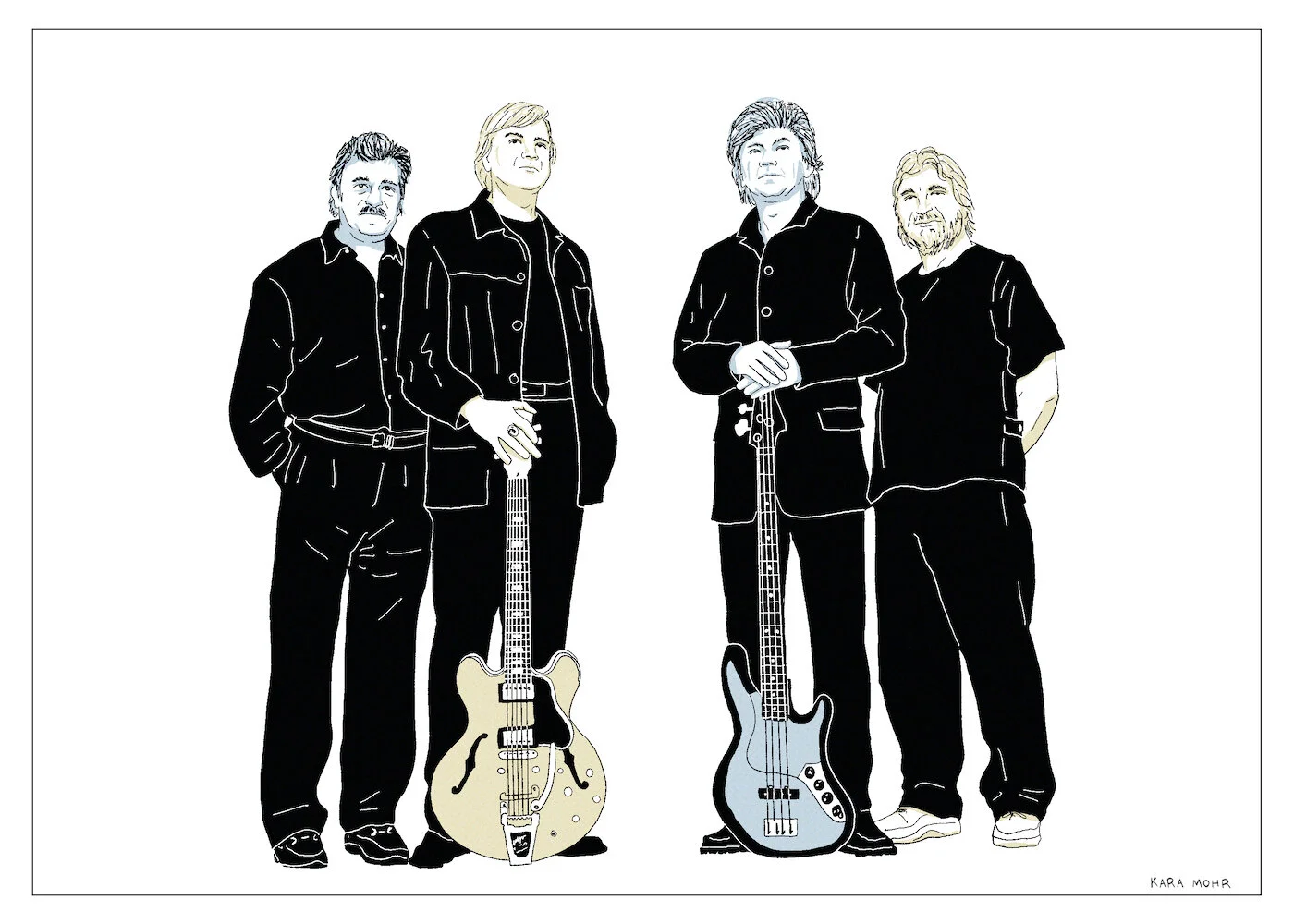

The Doobie Brothers “Brotherhood”

Today, they are the butt of a joke that started as an internet meme. They signify an amalgam of 1970s idealism, kitsch and grooviness alongside early 80s cool, coked up excess. All because of four albums they released between 1976 and 1980, and because of Michael McDonald’s proximity to Steely Dan, Christopher Cross and Kenny Loggins. Because of that, The Doobies are Twitter jokes and Spotify playlists more than they are “China Grove,” “Black Water,” “What A Fool Believes” and the bootlegging scandal from “What’s Happening!!” For nearly a decade, however, they were the American monoculture. Not The Eagles or Fleetwood Mac or M*A*S*H. The Doobie Brothers. They were the opposite of a punchline. The opposite of any one thing. They were everything. Then, one day, everything became too much and they were gone. By the time they came back, everything had changed. Everything, except The Doobie Brothers.

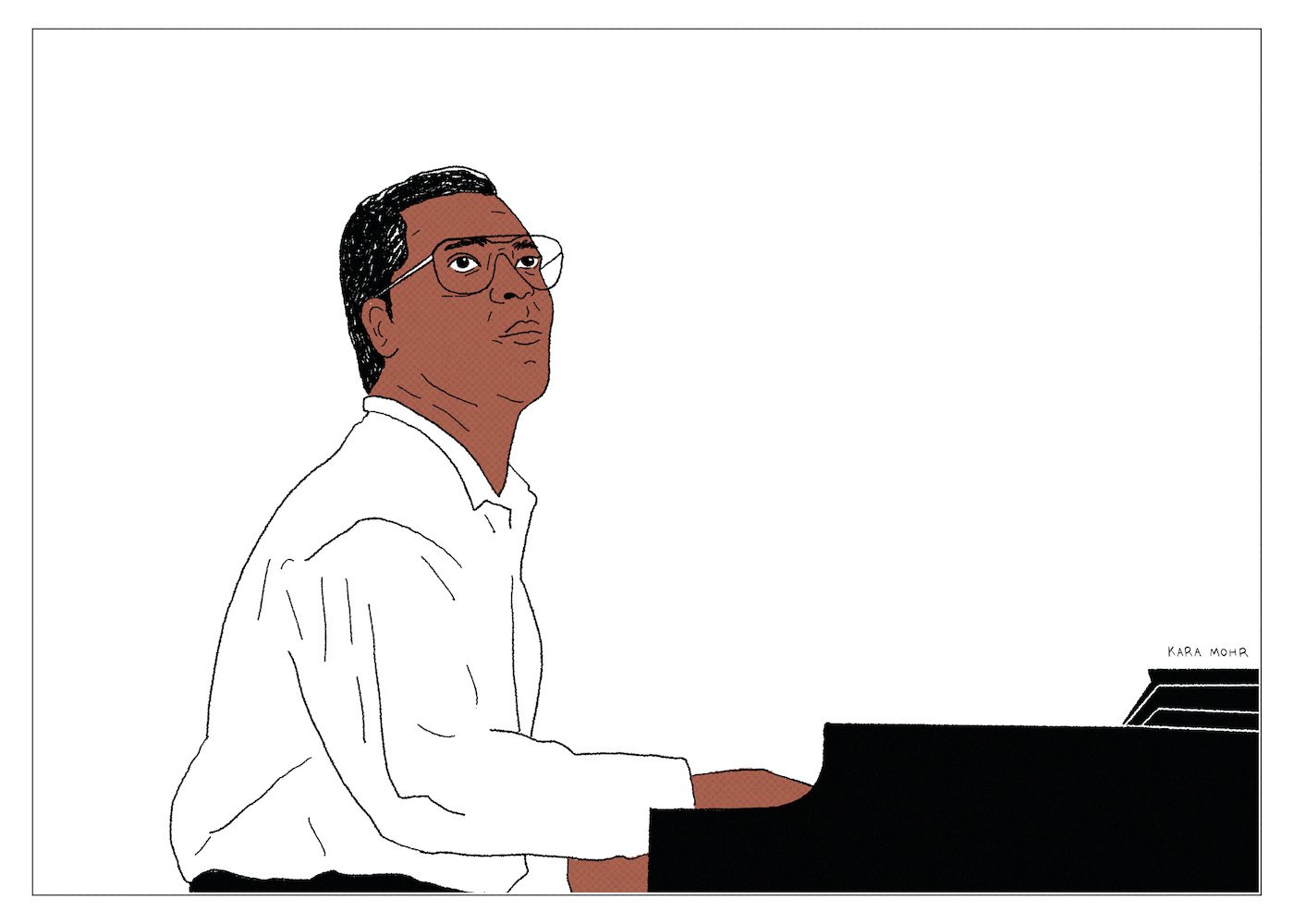

Booker T and the M.G.’s “That’s the Way It Should Be”

We are living in the golden age of music documentaries. In the last year alone, we got “Get Back,” “The Summer of Soul” and “The Velvet Underground.” Before those, there was the one about Ronnie James Dio and the one about Sparks and the Alanis one and the Poly Styrene one and, oh, that Karen Dalton one. It seems like every year, as part of the battle for streaming service supremacy, we get dozens of new additions to the canon. But the one that, for some reason, has yet to be made is the one about the bi-racial house band for Stax Records who made Otis Redding sound like Otis Redding and who were, in their own right, among the most important, but least documented, bands in R&B history. In 1994, seventeen years after their “last” album, they returned to make it final. Even in middle-age, Booker T. and the M.G.’s were flawless but soon forgotten.

Jim Palmer “The Unnatural”

In 1991, just months after forty-three year old Nolan Ryan had thrown yet another another no-hitter, but six years after forty-nine year old Jim Brown was bested by Franco Harris in the forty-yard dash, Jim Palmer was making a comeback. The former Orioles great was forty-five at the time and already a member of the baseball Hall of Fame. To some, the decision only confirmed their long held view: That Palmer was vain — a genetically gifted prima donna who required outsized attention. Fans, meanwhile, knew the the other Jim Palmer — the one who’d who’d spent decades playing through pain, getting booed and doubted, while still delivering pennants for the O’s. They saw the return as the last comeback in a career of comebacks for an unnaturally great pitcher who — yes — happened to resemble “The Natural.”

Chicago “Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus”

Some albums remain hidden because they were not made for public consumption. “The Basement Tapes” comes to mind. Others sit on the shelf because of incessant tinkering. “Chinese Democracy” might fit that bill. Sometimes, as with The Beach Boys’ “Smile” or Jeff Buckley’s “Grace,” the issues are entirely more human. But “Stone of Sisyphus,” Chicago’s thirty second album, recorded to be their twenty second album, is a different sort of animal. It was not released for the most obvious and depressing of reasons: their record label hated it. In its wide embrace of Rap, Slow Jams and Phil Collins, “Sisyphus” marked a return to the band’s eclectic roots. But in its wanton disregard for hits, it also served as a final farewell to the Cetera afterglow and an uncertain hello to the great unknown.

Genesis “Calling All Stations”

We wondered how they could carry on post-Phil. But their story was all about carrying on. First they lost co-founder Anthony Phillips — the “Pete Best” of Prog Rock. Then shape-shifting Prog-king Peter Gabriel. Then guitar savant Steve Hackett. And then, finally, pop icon Phil Collins. By 1996, there were only two men left. Tony on keyboard and Mike on guitar. But, how do you know when it’s time to quit? Why wouldn’t you try to keep going? Sometimes you need tangible proof that it won’t work. And so, Genesis was reborn (again). This time, featuring a younger, grungier, Scottish singer — Ray Wilson of the band Stiltskin. It turned out that “Calling All Stations” was all the proof anyone needed. It was the final Genesis album.

Van Halen “Van Halen III”

Gary Cherone never had a chance. He was the second step dad for a generation who didn’t want another step dad. Back in 1985, we were OK with divorce. It was a sign of the times. We rolled our eyes a bit at Sammy, but we also tolerated him and secretly liked him. We even understood the second divorce. Things happen. People grow up and cut their hair and take up golf. But the almost reunion with Dave and the ensuing PR stunts were not OK. And the ensuing addition of the guy from Extreme was so completely not OK that, by the end of 1996, the Van Nation was up in arms. To this day, “Van Halen III” ranks among the most reviled albums that, I suspect, very few people have actually heard.

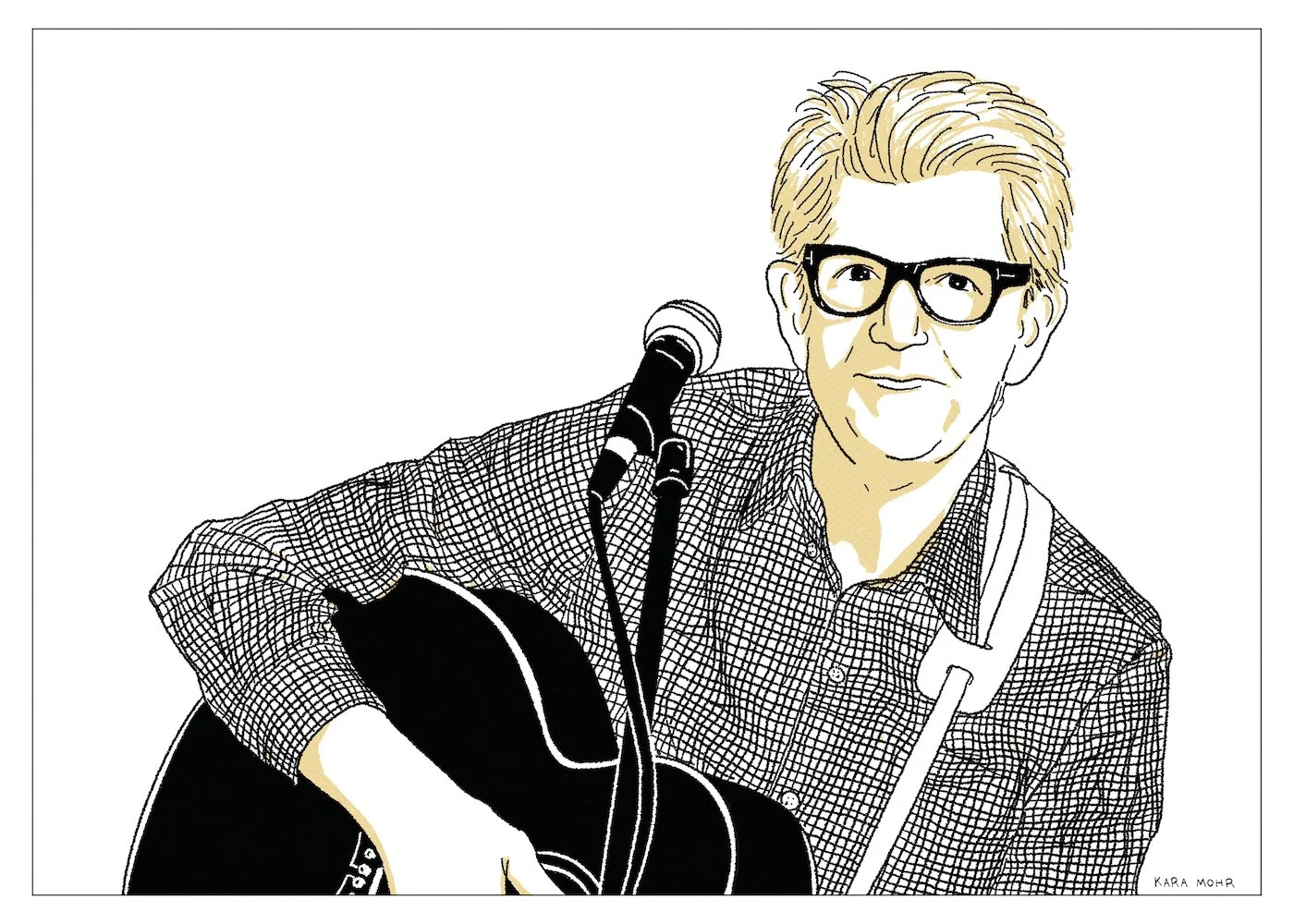

Nick Lowe “The Impossible Bird”

Once upon a time, Nick Lowe was the guy. He was New Wave’s beloved everyman — cool, but accessible. You might find him at the pub, you might find him on the Pop charts or you might find him in the studio with Elvis Costello. He married Carlene Carter and dated Lois Lane. To drop his name was to confirm your own hipness. By the early nineties, however, his time had come and gone. He was single, hitless, without a label and at the bottom of a pint glass. Amazingly, and with a little help from Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston, he dusted himself off and found a second act, functionally birthing his own genre of music in the process. Part Roots, part Country, part Rockabilly, and part Pop, the former mop-topped hipster became the white-haired songbird for discerning grown ups.

Albert Belle “Snapper”

He had a weird batting stance. He crouched right on top of the plate and then leaned in even further. At times, his head appeared to be firmly in the strike zone. When he got set, he did not budge. And, until the pitch was thrown, he cast a murderous gaze upon the pitcher. There is truly no better adjective for his expression. If somebody glared at me the way that Albert Belle glared at Greg Maddux in the 95 World Series, I would probably call the cops. To suggest that he was the best hitter of his era is defensible, but highly debatable. To claim that he was the angriest or most hateful batter, however, is not up for discussion.

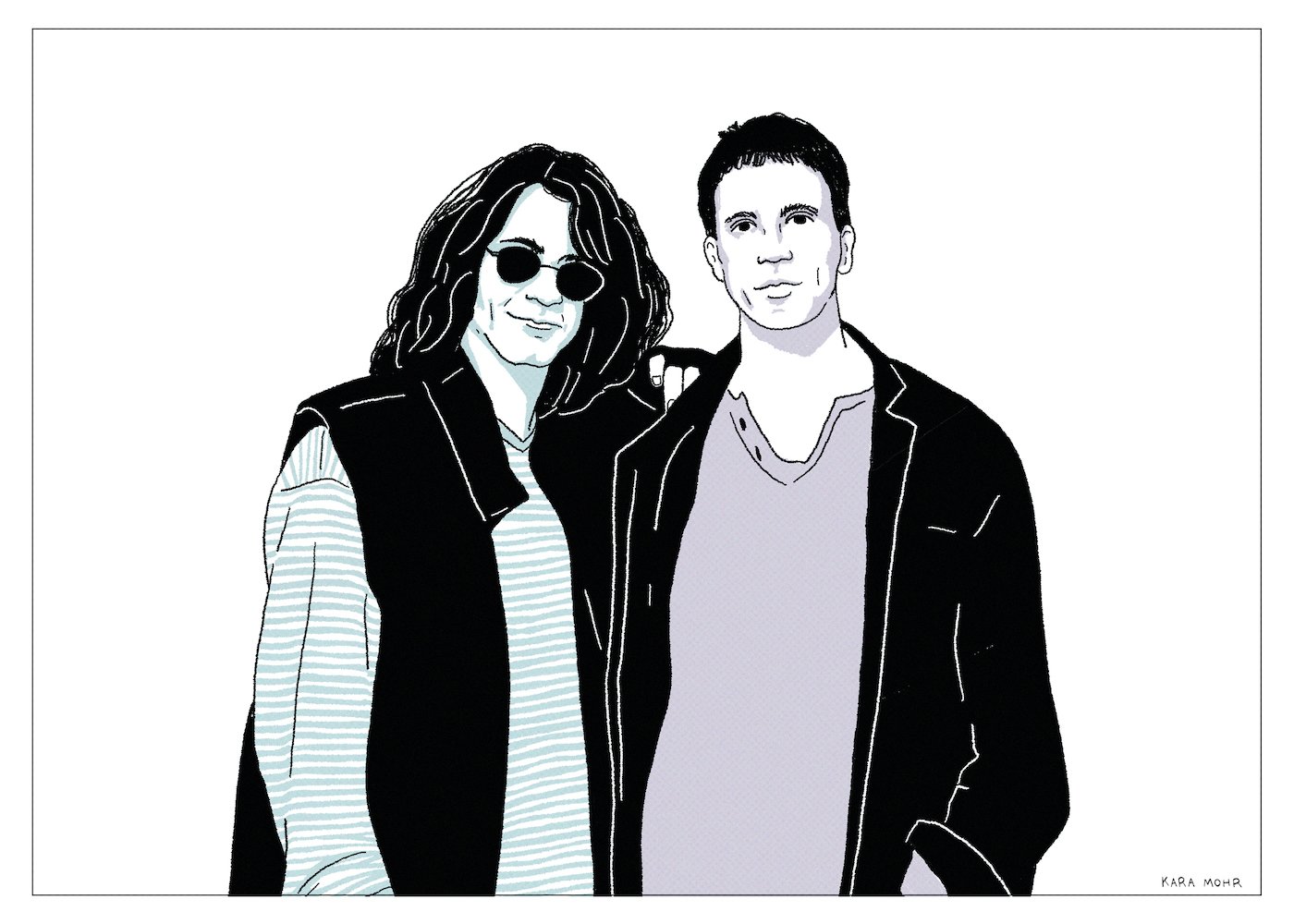

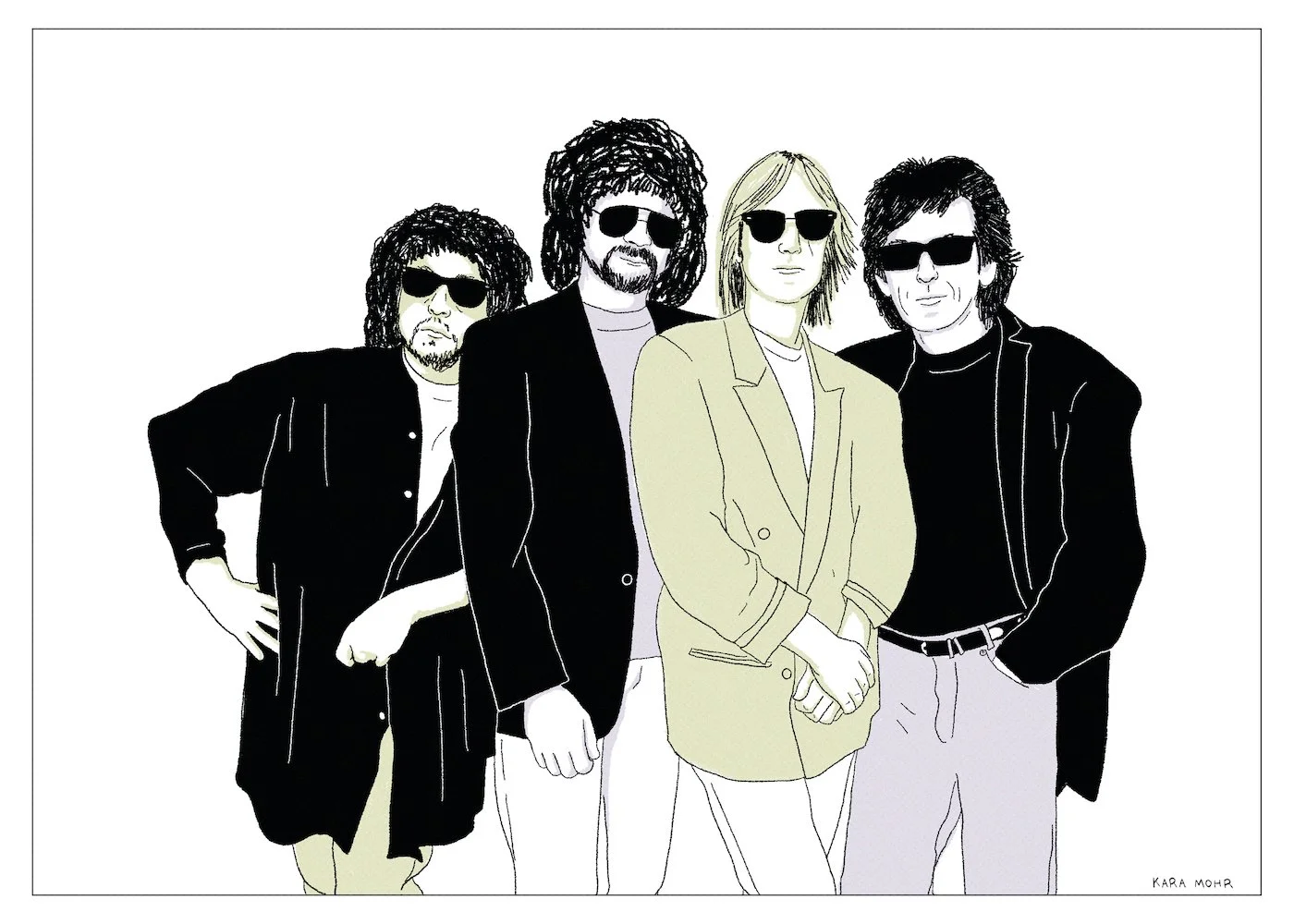

Traveling Wilburys “Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3”

The Traveling Wilburys were a “Supergroup” in name only. In reality, they were just a casual hang among middle-aged friends and admirers, who also happened to be Rock royalty. In 1988, they looked like half of an over forty, softball team from the Hollywood Hills — bad hair, extra paunch and beers after the game. The Wilburys’ debut is appropriately remembered for its easy going harmonies, for a couple of endearing hits and, sadly, for Roy Orbison’s passing. Many years later, it survives as a celebration (and commercialization) of “Past Prime.” History has mostly forgotten, however, that there was a follow-up album, complete with a bad “dad joke” for a title.

Air Supply “The Vanishing Race”

In retrospect, Air Supply seems unfathomable. Graham Russell looked like an overgrown Jeff Daniels with feathered hair. Russell Hitchcock was tiny, with a massive perm. Together, they looked like a Saturday Night Live sketch for a Hallmark ad about roller-skating buddies who loved cats. They were the naked, bawling men of Soft Pop who sang songs for exhausted, dejected, lovelorn ears. But, between 1980 to 1983, they scored eight consecutive top five hits, a feat only matched previously by The Beatles. By 1986, they were gone, off to redesign their Quaalude Rock for middle age and to celebrate their second career in the Philippines.

“Two Princes” (Spin Doctors) vs “Remedy” (The Band)

In 1993, The Spin Doctors gave MTV the winter hat plus hacky sack vibes the network sorely needed. Their unavoidable mega-hit, “Two Princes,” topped the charts and introduced Jam Band culture to the suburbs. Meanwhile, that same year, The Band reformed without frontman Robbie Robertson to make “Jericho.” One of the few originals from that album was “Remedy,” which charted nowhere and is remembered only by the most loyal of devotees. So, here’s the question: What’s better — an unforgettable song by a critically derided band in their prime or an unexceptional one from a beloved artist well past their prime?

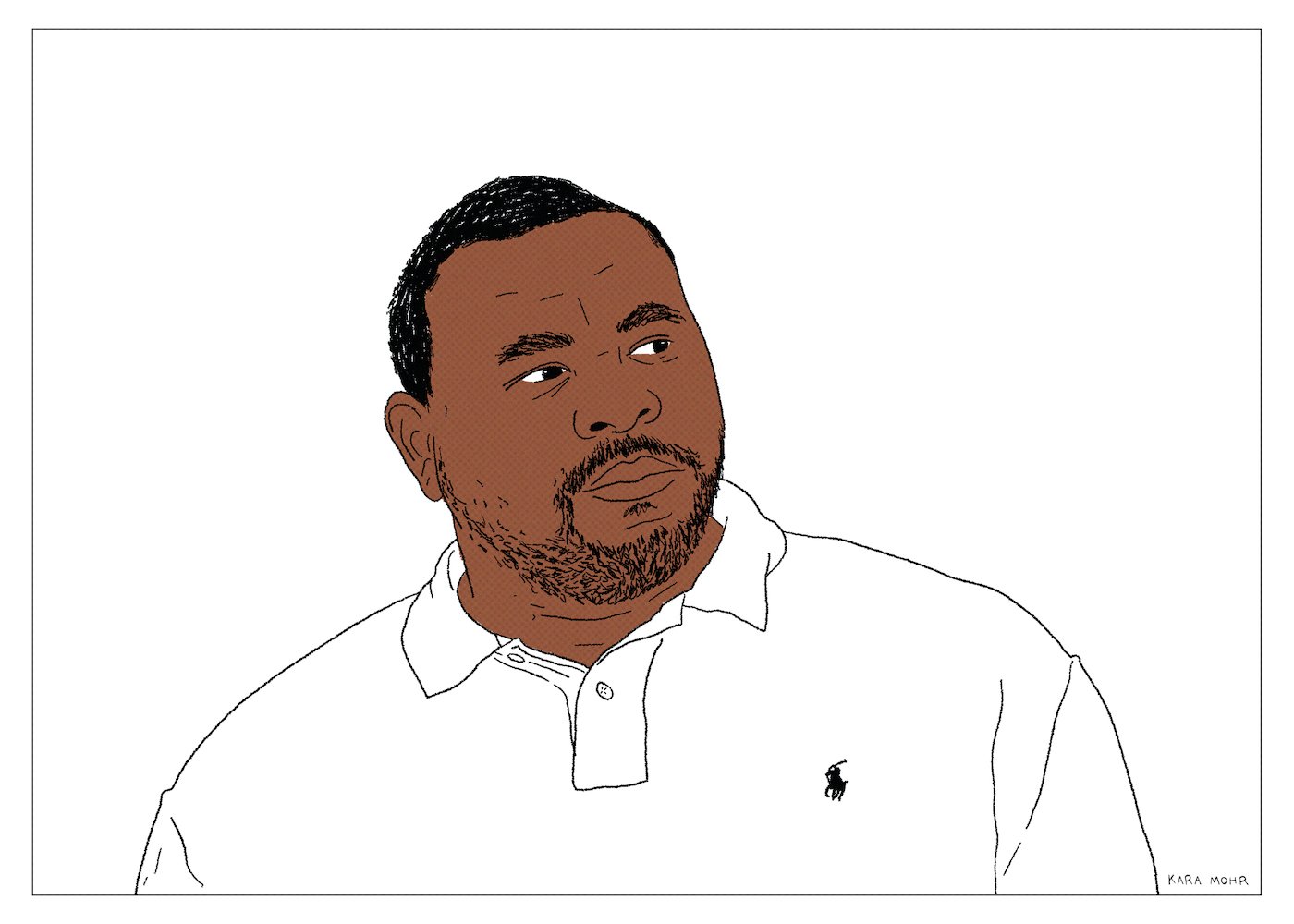

Eddie Murray “Steady Eddie”

To this day, it still bums me out. It’s been twenty five years, longer than Eddie’s playing career. I’ve had plenty of time to let things go. But not this. I can’t quit it. At least twice a year, I have dreams where he’s still playing. I see him on TV up at the plate, no batting gloves, adjusting his belt, glaring at the pitcher. They called him “Steady Eddie” because he was exactly that. He wasn’t the most prodigious power hitter or the slickest fielder or fastest runner. But for the first half of his career, he was the most complete hitter in the game. But then, in 1997, at the age of forty-one, he was demoted to the minors before finishing out his great career with a whimper. I am certain that he’s moved past the indignity. But, I have not.

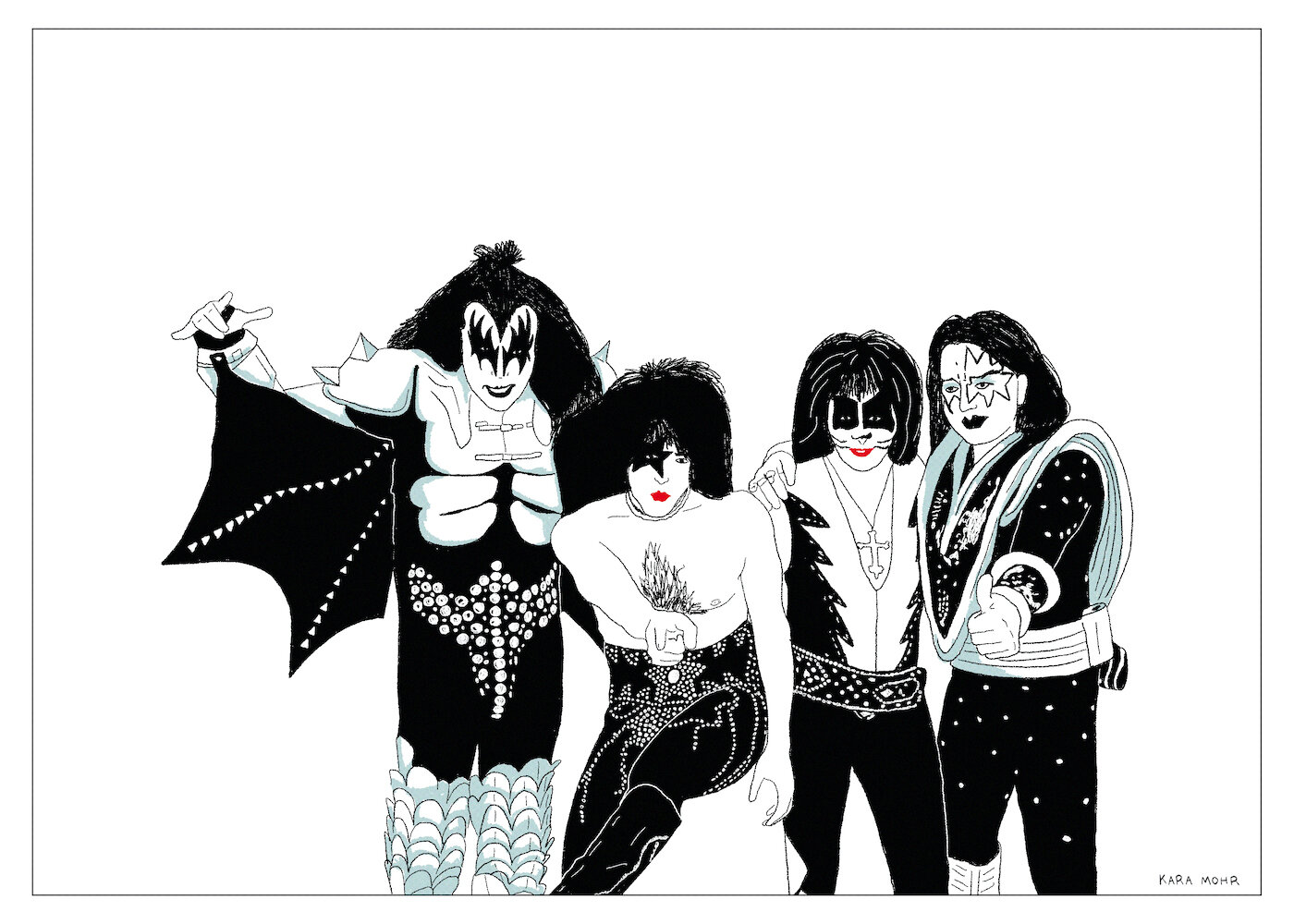

KISS “Psycho Circus”

As success stories go, Kiss’ is perhaps the most unconventional. They’ve had thirty Gold albums, more than any band before or since. A 1977 Gallup poll named them the most popular band in America. Gene Simmons is reportedly one of the twenty wealthiest living musicians. To me, however, they were barely a band. They were comic book ghouls. They were a pinball machine. They were the faces that embellished a demonic laundry bin that my mother one day deposited in my bedroom, without explanation. In 1998, having recently reunited, Kiss made it very clear: Their product was still heavy and basic. And their mission was still profit.

Toto “Mindfields”

Toto was a lab accident. Obviously, not a tragedy, like Chernobyl. More like Bruce Banner getting exposed to Gamma Rays and becoming The Hulk. Back in 1982, they sounded both hulkingly awesome and completely normal. They won Grammys. They sold over ten million records. They were proof that Rock music could be sonically pristine and exceedingly popular; that musicians could look just like regular guys -- or worse -- and still be stars; and that Pop music could be “all encompassing” (“in toto”). However, like many great experiments, over time, the evidence proved less conclusive.

The Moody Blues “Strange Times”

Although they are considered pioneers of both Psychedelic and Progressive Rock, The Moody Blues always sort of defied classification. Their music frequently sounded either too slow or too fast. They were once Classical in Modern times. Then, they were the oldest of the New Wave. In 1999, after an eight year hiatus, they returned to the world of Limp Bizkit and The Backstreet Boys. And, as always, they seemed both timeless and time-less.

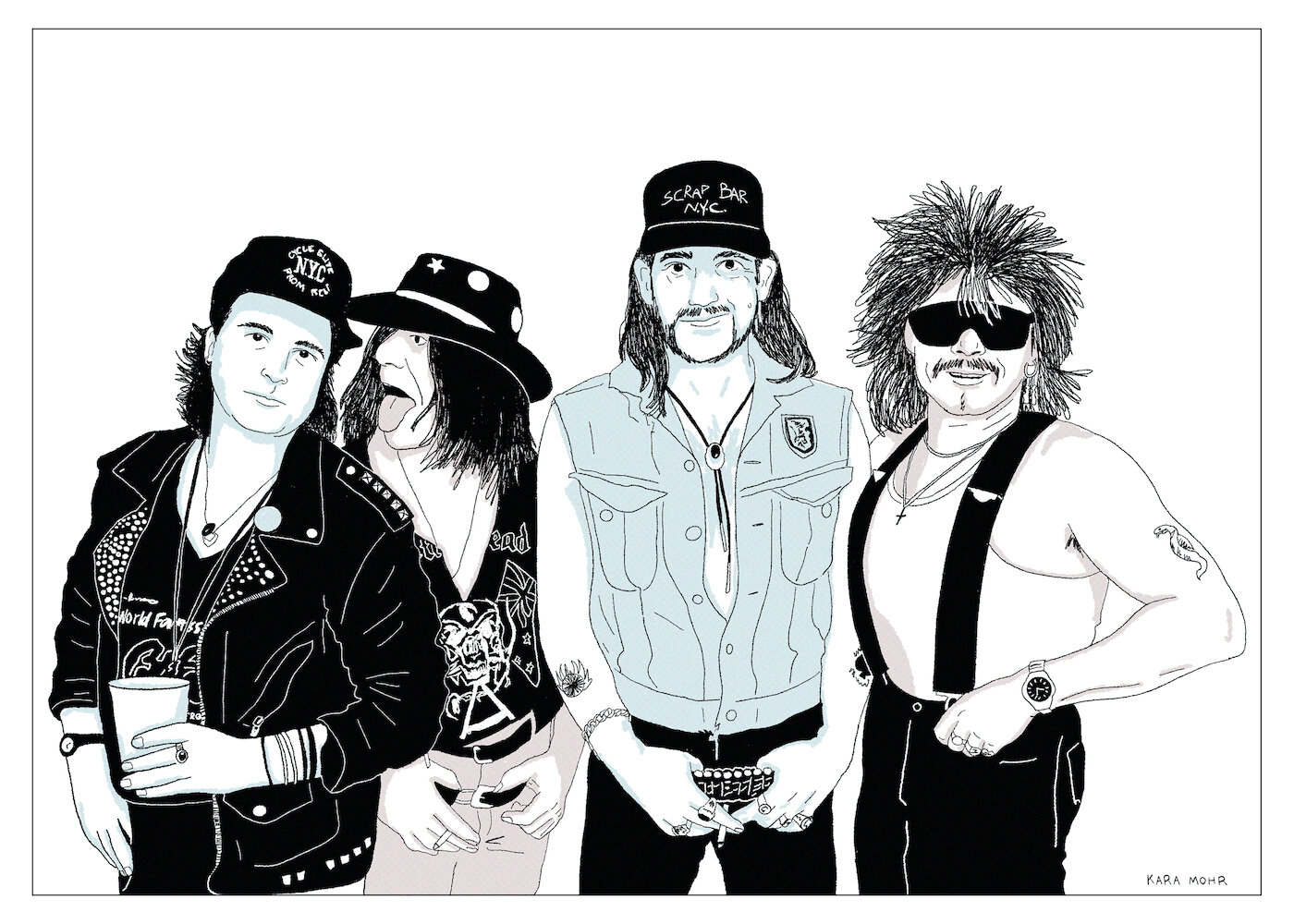

Motörhead “1916”

Like their snaggletoothed logo. Motörhead never really changed. Even when Lemmy was forty-five, transplanted to Los Angeles and caught between Hair Metal and Grunge. Even when Philthy Phil looked like a feral, drunk understudy from “Cats.” Even then, they could drop a dozen heat seeking missiles, armed with nuclear Stones and coked up Sabbath.

Eddie Money “Ready Eddie”

If you really understand Long Island, you know that it isn’t Billy Joel country or Lou Reed country or Mariah Carey country or Bernie Madoff country. It’s Eddie Money country. Money was the one hit wonder who, from 1977 to 1988, just couldn’t stop making hits. He was the guy who sang “Two Tickets to Paradise.” He was Bruce Springsteen with two sides of ham and half as much talent. He was the “King of Generic Rock” who, in 1999, finally realized that “generic” also meant “easily replaceable.”