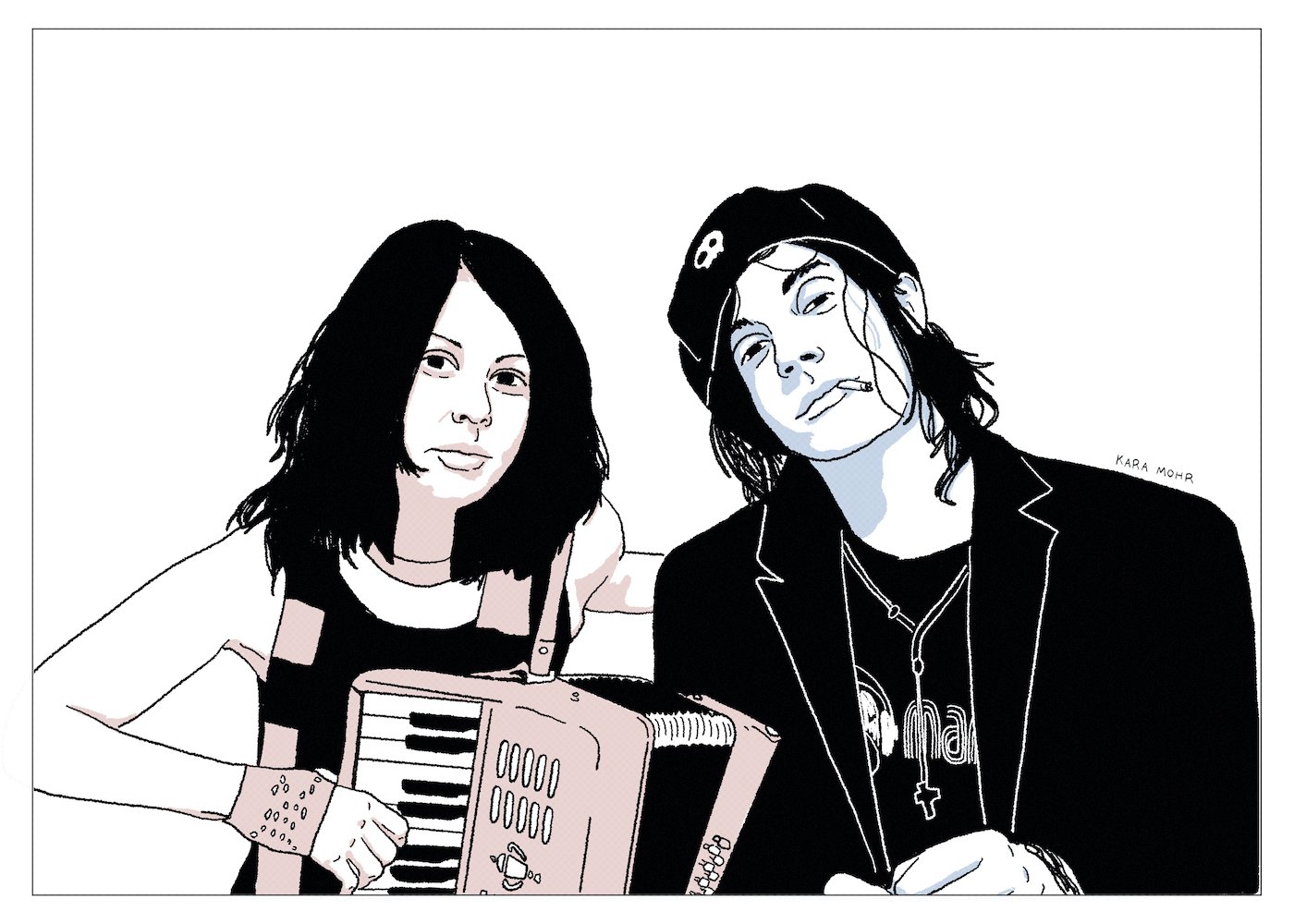

Black Mountain “IV”

Ten years, three studio albums and a half dozen side projects after their Pitchfork-feted debut, Black Mountain returned with “IV.” From its Hipgnosis-inspired cover, which screams Floyd and Hawkwind, to its bank of synthesizers, borrowed from Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson, “IV” is a total flex. It’s an epic album, daring and ridiculous enough to take its name from one of the most famous albums in the history of Rock and Roll. Black Mountain’s “IV” is obviously not Led Zeppelin’s “IV.” In fact, it’s their least bluesy, least metal, most spacey and most proggy album. A more accurate title might actually be “Light Side of the Moon.” The titanic riffs are still very much there, but they are not the thing. The synthesizers are sometimes the thing, but also not the thing. The thing that distinguishes “IV” from straight homage is the thing that has always separated Black Mountain from everyone else — the sound of Amber Webber’s voice paired with Stephen McBean’s. The sound of verdant soil and deep roots next to burnt twigs and leaves.

Blues Traveler “North Hollywood Shootout”

On so many levels, our aversion to Blues Traveler is ridiculous. Of all those Nineties Jam bands, why them? There were many lesser variations. Bands who couldn’t play with singers who couldn’t sing and jams that went nowhere. Blues Traveler was barely any of those things. They were a solid Roots Rock band with a mascot for a lead singer; far more exciting than their closest predecessor — Spin Doctors — and their more successful, distant cousin — Hootie and the Blowfish. If anything, their brief apex was a fluke — a product of commercial radio’s (and MTV’s) inability to separate Beck from Better than Ezra. For one strange moment in 1994, Modern Rock, Mainstream Rock, Pop and Adult Alternative formats all sounded oddly similar — jangly and towing a line between earnest and ironic. Basically, like the sound of Blues Traveler. On the other hand, reducing them to a bad haircut, does a grave injustice to the band. It also obscures the harmonica in the room — the dozens and dozens of harmonicas in the room.

Ray Davies “Americana”

As a musical style, Americana suggests something in between “Roots Rock” and “Alternative Country.” Stylistically, it's a fertile if ultimately narrow genre. But, Ray Davies’ “Americana” is not Whiskeytown’s “Americana.” Davies’ is as expansive as it is deep. It considers both the United States of America and the land mass that predated the country — the massive mountain ranges and the canyons and rivers and the natives and the cowboys. The freedom and independence and capitalism and Jazz and Blues and Soul. The New York and Los Angeles and high hopes and dashed dreams. All of it. The man who wrote “A Well Respected Man,” “Waterloo Sunset” and “Village Green Preservation Society” — the singer-songwriter who satirized and romanticized English life was enraptured with America. England consumed his mind, but America held his heart.

Ted Leo “The Hanged Man”

From 2000 through 2010, Ted Leo was the mainest of Indie Rock mainstays. He and his band released a string of reliably thrilling albums, distinguished by his breathless tenor and progressive politics. Ted Leo and The Pharmacists were so excellent, in fact, that it seemed a foregone conclusion he would one day break through. That Ted Leo would eventually be an important, prestige act felt inevitable. After all, they had their Billy Bragg and their Elvis Costello, so we could have our Ted Leo. He was simply too good — too musical, too smart and too hard working — to imagine any alternative. The sparkling reviews continued along with the steady uptick in sales, until he reached the height of sub-popularity. And then, just when we assumed something monumental was about to happen for Ted Leo, it did. But it was not at all what anyone expected.

Chain and The Gang “In Cool Blood”

Like Nation of Ulysses before them, The Make-Up were more legendary than popular. And so, just five years after they first appeared, the most stylish, most ideological band on the planet was dissolved. In the Aughts, Ian Svenonius (along with Michelle Mae and Neil Hagerty) formed Weird War, but because socialism might be bad for business, the singer spent most of that Aughts moonlighting as a subject slash contributor for Index Magazine — and anyone else who wanted his ideas and his hair for their pages. By 2009, he was more an essayist, a great interview, a great photoshoot, and a hipster cad than he was a rock and roller. He was to Vice what Fran Lebowitz was to Vanity Fair. Until one day — when he’d either run out of ideas or when he had too many out of them — Svenonius started another new band. Chain and the Gang started as a lower stakes, rotating cast of friends and acolytes, sponsored by Calvin Johnson. By then, fans (and critics) were familiar with Svenonius’ Post-Structuralist, Marxist provocateur shtick. What they were less familiar with was his winking, hip-shaking good times.

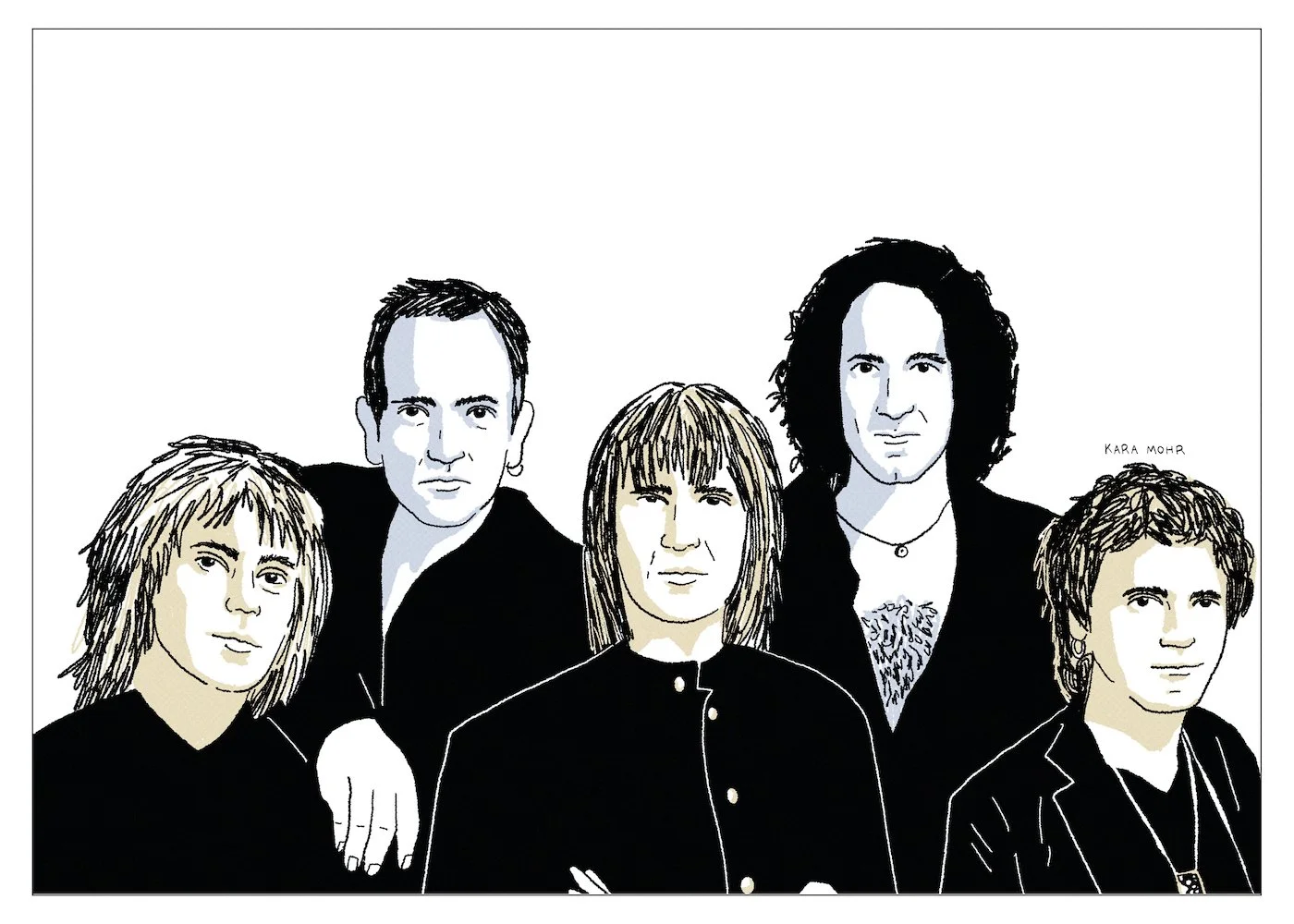

Squeeze “Cradle to the Grave”

Though early on they were compared to Lennon and McCartney, Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford were much closer to Elton John and Bernie Taupin. Tilbrook was a master tunesmith and Difford was an equally gifted wordsmith. For the most part, however, (and unlike Lennon/McCartney) they worked separately, fitting and refitting their own parts to the others’ material. Tilbrook, the more gregarious and intuitive one — he leaned towards the Beatles. Difford, more contained and cerebra, leaned towards Post-Punk. One man was blonde. The other brunette. They were childhood classmates, but, from the outset, and in spite of their shared interests, they were also a study in contrasts. During Squeeze’s first break-up, the two men actually made an album together, under their own names. After the second divorce, however, things got ugly. Jools Holland was gone, the hits dried up and Difford bottomed out. From the outside, it seemed certain that Squeeze was done. From the inside, it appeared even worse.

Green Day “Revolution Radio”

Twenty-two years after they first broke out with “Longview,” twelve years after they were the biggest Rock band in the world, eleven years after they inadvertently bankrupted Lookout! Records and four years after Billy Joe melted down onstage, Green Day was, once again, a band with uncertain prospects. And yet, their twelfth studio album was not a sharp turn or a step back or a leap forward. “Revolution Radio” was more a shoring up of lost ground — more like downside protection. All three members of the band were well into their forties by the time of the record’s release, meaning that the snotty charms of their youth would not play the same. Self-loathing and fuck you's present much differently in middle-aged millionaires than they do in twenty year olds. And so, in the year that Donald Trump was elected President and at a time when album sales were usurped by track steams, Green Day was in the unenviable position of having to question both their form and their function.

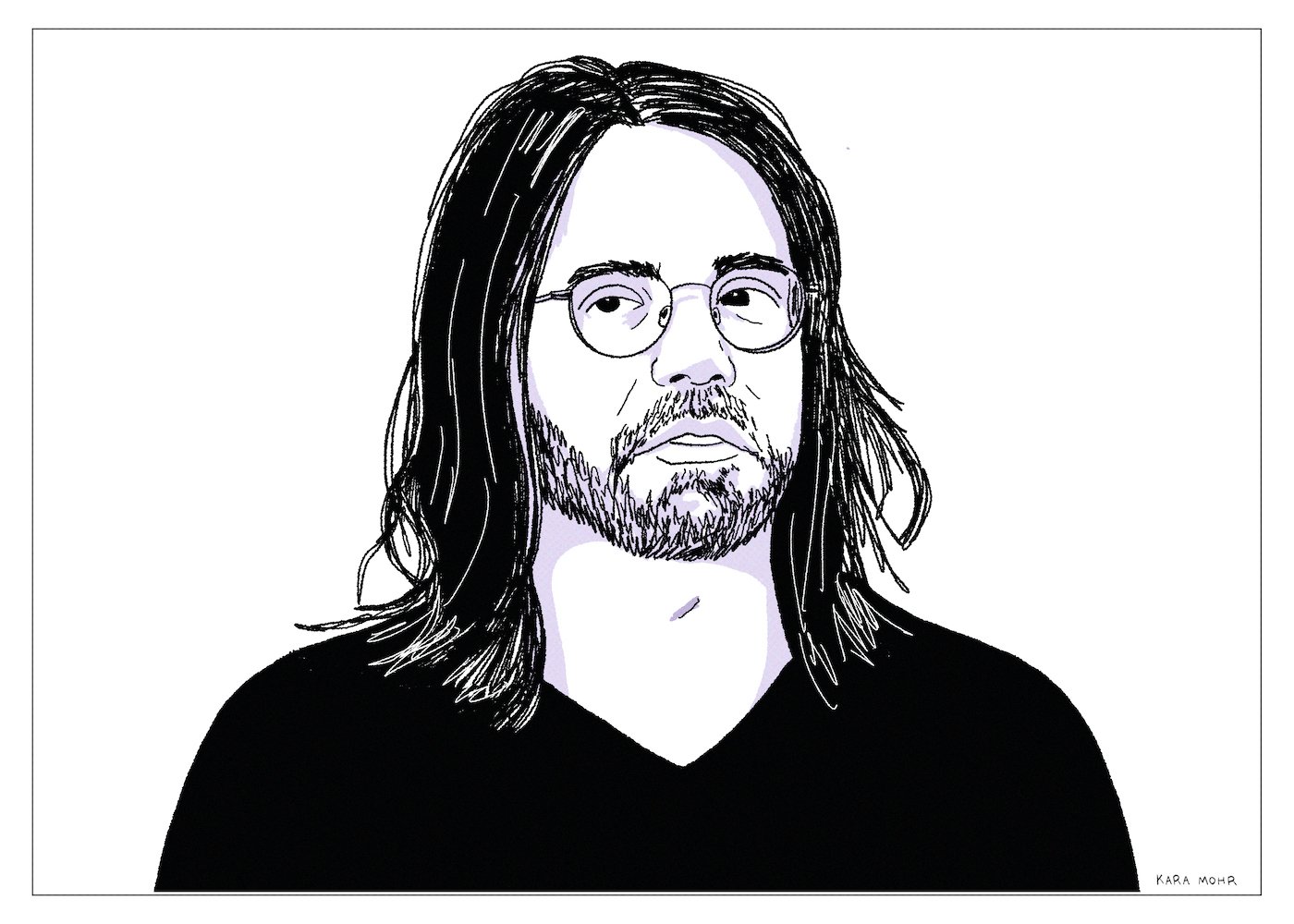

Tom Verlaine (1949-2023)

Of all of the many wonderful things said about Tom Verlaine this past week, the most moving words came, unsurprisingly, from Patti Smith. Her eulogy for The New Yorker, entitled “He Was Tom Verlaine,” was typically elegiac, like a series of black and white photographs narrated with poetic beats and prosaic secrets. Amid the generous obituaries and Twitter tributes — written mostly by strangers — Patti’s essay was so unusually revealing, not because she was betraying any confidences, but rather, because prior to this week, and despite the fact that I spent decades enamored of him, I knew so little about Tom Verlaine. He was not a recluse like Jeff Mangum or an outsider like Syd Barrett or Roky Erickson. But it seemed that, ever since “Marquee Moon” changed everything — and nothing at all — Verlaine was slowly, silently walking in the opposite direction from everything that fans (like me) most wanted from him. His entire career — seemingly confirmed by Patti Smith herself — is a reminder that love is so much more about what we don’t know than what we know for sure.

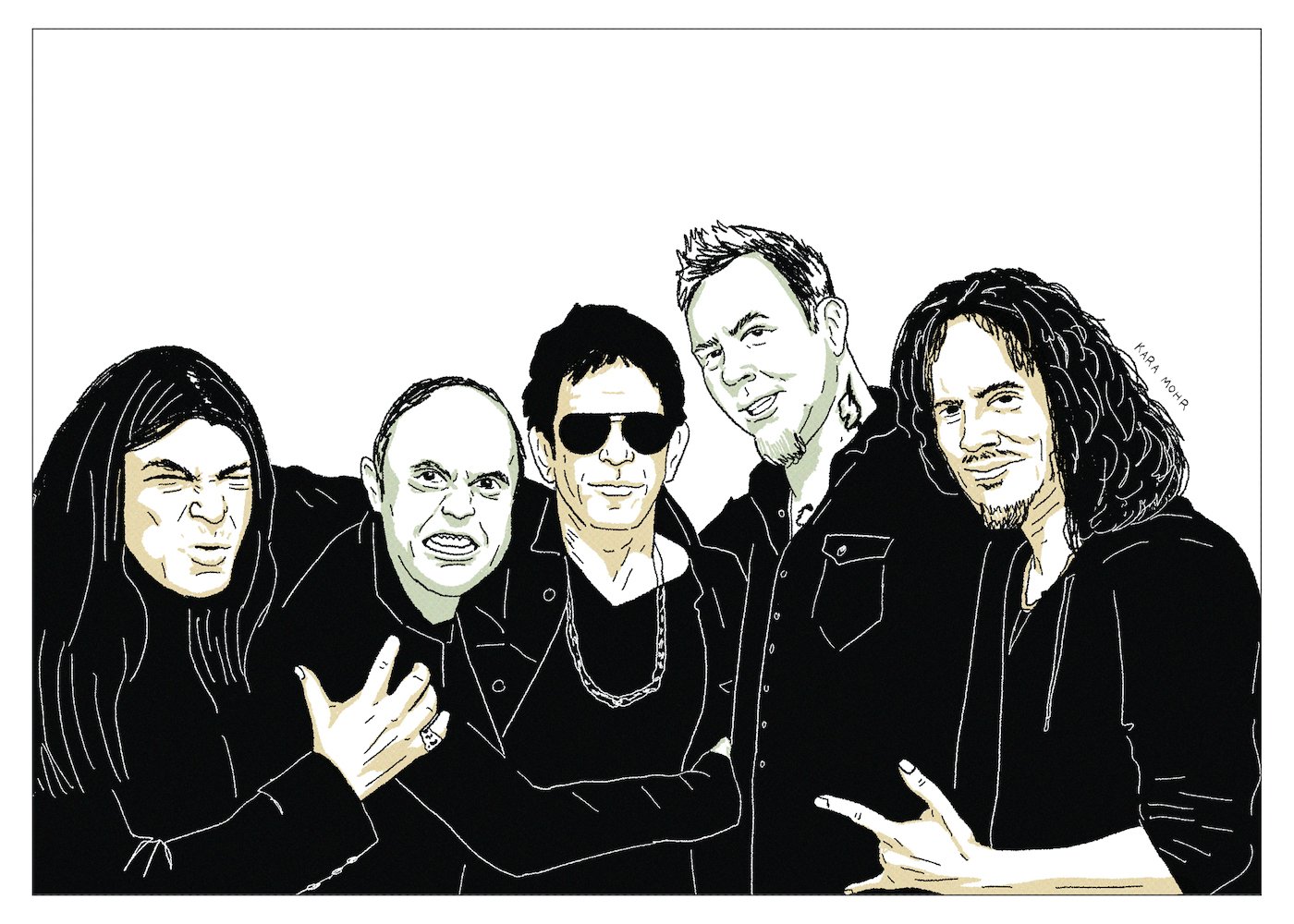

Lou Reed and Metallica “Lulu”

Given how few people have actually heard the album, and how few of those people are interested in anything beyond the stars involved, the volume of “Lulu studies” is staggering. But the divergence of the various theses is so bold as to suggest that either (a) people are listening to different albums or (b) nobody knows anything. There is, of course, overlap in the various perspectives — but less than I would have assumed. Many simply believe that “Lulu” is a historic failure — a bloated pretentious hour and a half of noise and nonsense. There are others who view it as an act of artistic bravery from two legendary artists, committed to a vision and unconcerned with failure. And, finally, there are those who believe that “Lulu” is misunderstood. Nowhere among the three points of view, however, can you find a faction who boldly proclaims: “Lulu is awesome.”

Marah “Marah Presents Mountain Minstrelsy of Pennsylvania”

The first wave of Dad Rock is canon — Dylan, The Band, Petty, The Boss. Occasionally, it veers into Indie or Alternative Rock (REM, The Replacements) or headier stuff (The Dead, Steely Dan). But, broadly speaking, it’s American Roots Rock for educated men who are older than thirty but younger than sixty, who are likely to drink craft beers and who desperately want their children to understand the glory of “Jungleland.” The second wave of Dad Rock is still a work in progress. In the early Aughts, bands like The Hold Steady and Band of Horses and Arcade Fire began to make their cases. Some of the neo-Dad Rockers were cut from The Boss’ cloth (Gaslight Anthem, The Constantines) and others were perhaps closer to Dylan (Bon Iver, Sufjan Stevens). But the ones who should have been kings — the ones who got it all started but then got lost in the plot — were Marah.

Keith Rainere “Totally Innocent Prog Rock Genius”

According to Nancy Salzman, at some point just before scoring the world’s highest IQ and becoming one of the world’s three greatest problem solvers, Keith Rainere taught himself many musical instruments, including the piano, which he could allegedly play at a concert level. Of the many claims made by NXIVM, I found this one most confounding simply because it is the most disprovable. During the nine hours of “The Vow’s” first season, the only proof we get of Rainere’s musical gift is a brief, middling performance of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” — a piece generally taken on by younger students in the first few years of their studies. On the basis of this showing, it’s hard not to conclude the obvious: Keith Rainere is no Keith Emerson. So, why? Why did he make such a bold and obviously false claim? IQ tests can be forged. Problem solving is hard to measure. But musical aptitude is hard to fake. The answer to my question arrived in the late Spring of 2019. According to the New York Post, some time after mastering all of those instruments but presumably before breaking the IQ test, Keith Rainere got really into Prog Rock — specifically Yes and Genesis. Which explains everything.

Bon Jovi “This House Is Not for Sale”

Though they were no longer America’s Biggest Rock Band, Bon Jovi could still sell (many) millions of albums. But it was clear to anyone who was paying attention that things had changed. Jon cut his hair and took up acting. Richie married Heather Locklear. Over the course of three decades, they’d traded in grit for nostalgia. Their fearlessness was subsumed by trite optimism. And though they’d sustained their spot on the charts, they’d regressed from something iconic to something more generic. By 2015, they had to confront the existential risk that all Arena Rock bands some day face: the challenge of being both universal and distinct. Many great bands had fallen into that chasm before: Journey, Foreigner and REO Speedwagon to name a few. But, not Bon Jovi. In just a few years, and without Richie Sambora, they went beyond arenas. Beyond namelessness and facelessness. They became the Bud Light of Rock and Roll — the highly consumable, mostly bland complement to Fox Sunday football.

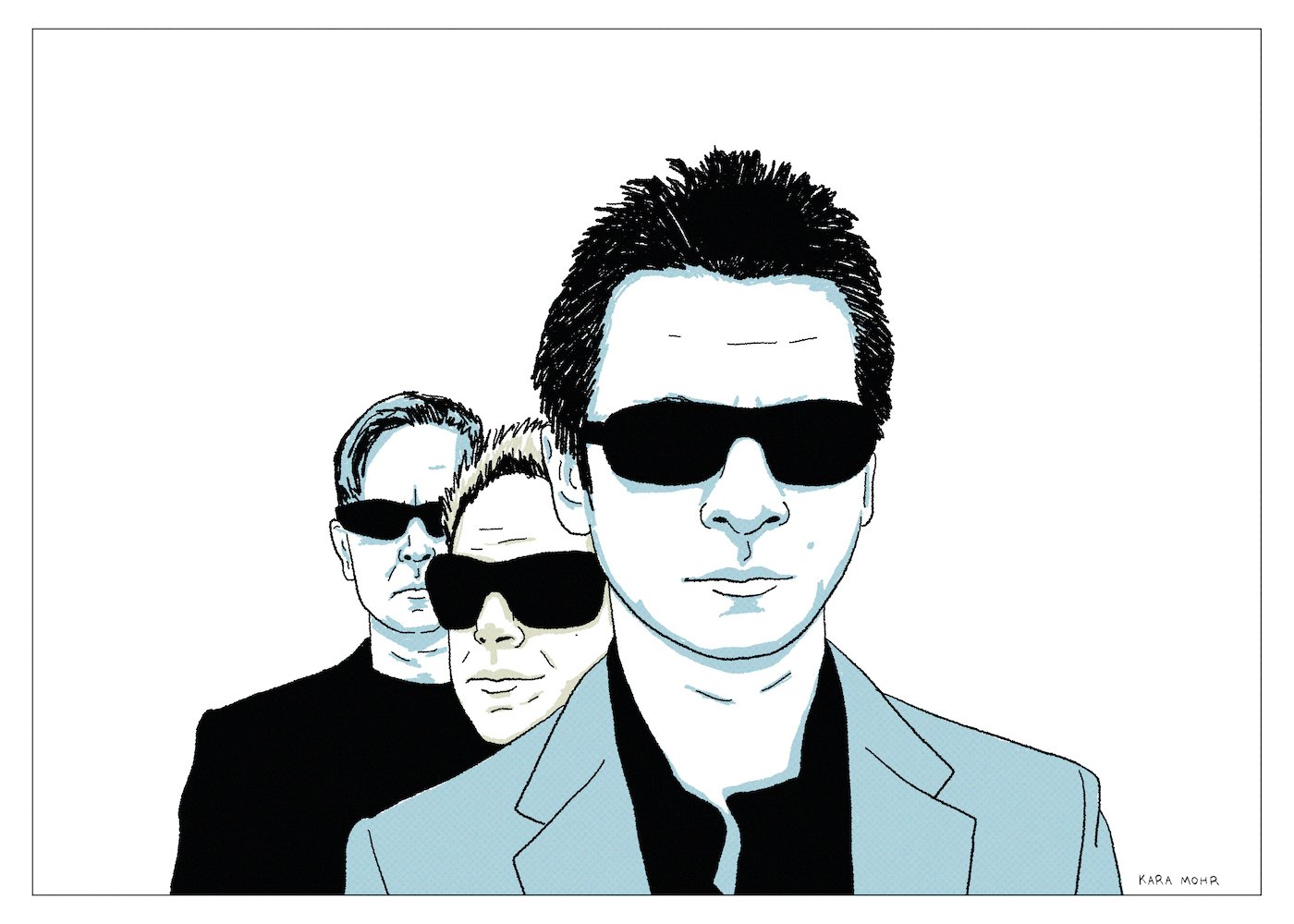

Depeche Mode “Playing the Angel”

By 1990, having graduated from new wave romantics to industrial futurists to “goth cowboy junkies,” Depeche Mode had inexplicably managed to conquer the world. And though they were churning — even rotting — on the inside, “Violator,” from that year, was inarguably their commercial and creative peak. It was also very nearly the death of the band. During the 90s, Gahan sunk deeper into heroin addiction, Gore was literally seized by alcoholism and Fletcher suffered crippling anxiety. The downward spiral continued until 2005, when Gahan, newly sober, and Gore, not sober and soon to be divorced, retreated with Fletcher to Gore’s home studio in Santa Barbara. The resulting album, “Playing the Angel,” was a deceleration and introversion following decades of the opposite. And while it was mostly a beloved album, it was not “peak Depeche Mode.” It’s a downing of the ante. It was also a minor miracle, recorded at the moment when the un-killable band suddenly seemed all too mortal.

Def Leppard “X”

Def Leppard were once as American as apple pie. More than Bruce or Petty or Johnny Cougar, they were the soundtrack of the American Heartland. They were the grist for Rock radio, churning out pristine, semi-heavy, fully melodic singles, engineered by the future Mr. Shania Twain. With the arrival of Grunge and Alt, however, came the annihilation of Hair Metal. And though they did not precisely fit the genre, Def Leppard was a casualty of the 90s. On the brink of extinction, they tried everything to survive. They tried sounding like Stone Temple Pilots. They tried sounding like themselves. And then, finally, desperately, they tried the unthinkable. They hired wunderkinds Marti Frederiksen and Max Martin and made a bunch of tracks that resembled the third best songs from “American Idol,” if recorded by Bryan Adams for the Nordic market. On “X,” Def Leppard tried mightily to reclaim lost ground, but ultimately fell short of “popular” and landed awkwardly in the neighborhood of “pop.”

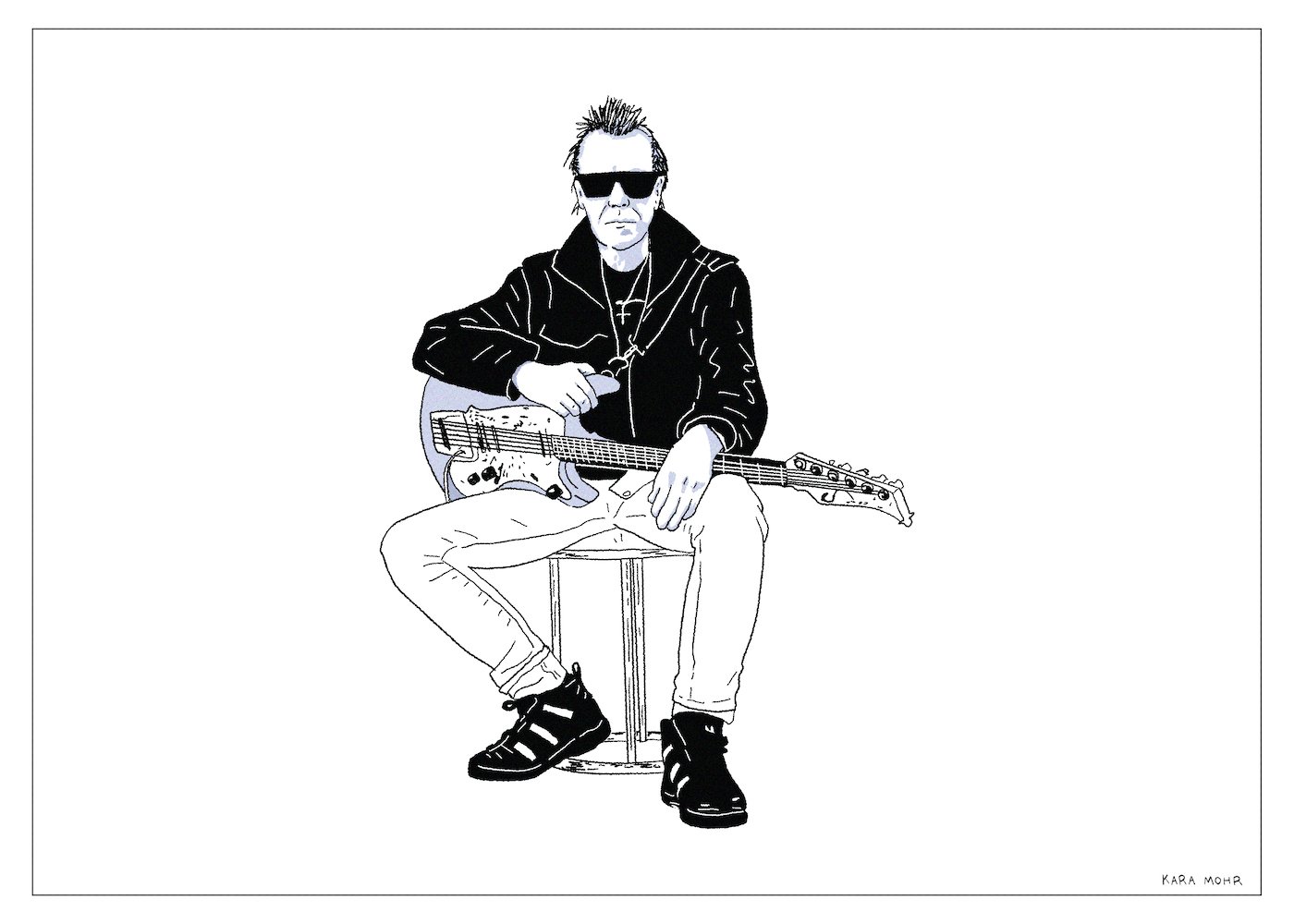

Link Wray “Barbed Wire”

After a dormant decade living a quiet life on a remote island in Denmark, the man who’d invented Hard Rock discovered his new sound. Amazingly, sixty-something Link Wray was faster, louder and scarier than his younger self. Whereas “Raw-Hide” and “Rumble” were soundtracks to noirish Westerns, his final performances sound like The Replacements scoring a 1950s drag race. Flanked by a band of much younger devotees, Grandpa Link returned to salvage his legacy. In spite of his indisputable greatness, he’d failed as a pop star. Failed as a folkie. And failed as a proto-punk. So, this time out — his last time out — he opted for all three incarnations. He wore black sunglasses, a leather jacket, a white tank top and a two foot ponytail and a thinning pompadour. He looked as though he’d either lost his mind or that he meant business. Or possibly both.

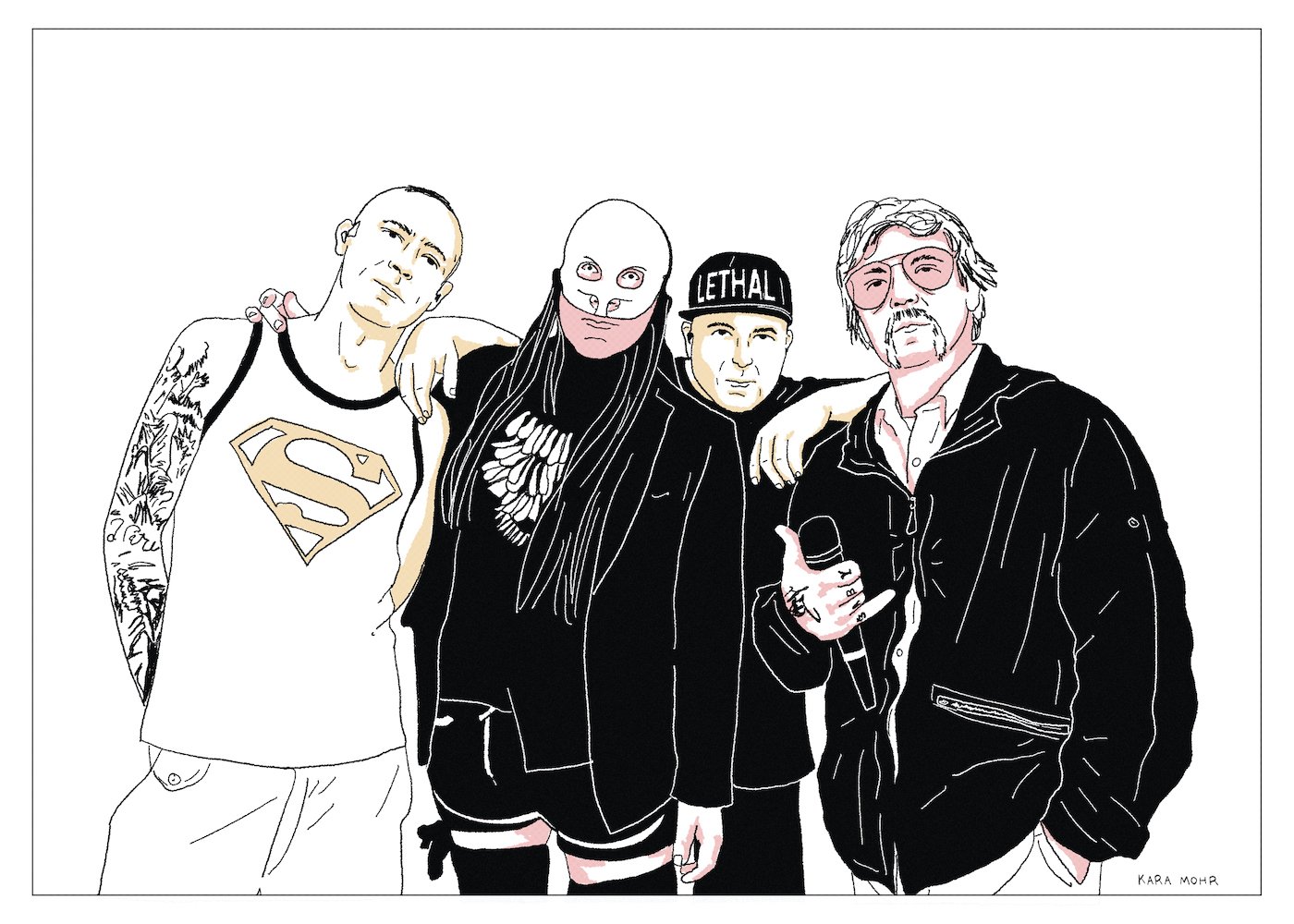

Limp Bizkit “Still Sucks”

There’s this rich, aging Floridian who’s prone to wearing red hats, saying horrible things about women, insisting that he’s a victim and flirting with Russia. Many Americans consider him to be a terrible, dangerous human. But to some, he remains unassailable -- almost godlike. His name, of course, is Fred Durst. The villainization of Durst is almost too easy. His name is basically synonymous with “douche.” And as popular as Limp Bizkit once was, they were more so reviled. To many, the band’s frontman has always been an under-talented, rage spewing bro. His litany of offenses is significant and the counter-argument is not terribly clear. Durst, however, has been consistent with his own defense: He is the lifelong victim of bullying and rejection. He’s horrified that his band’s music was co-opted by misogynists. He’s not the bad guy. He knows his band sucks. He’s in on the jokes. If anything, the joke is on us -- his critics. In fact, we are the bullies.

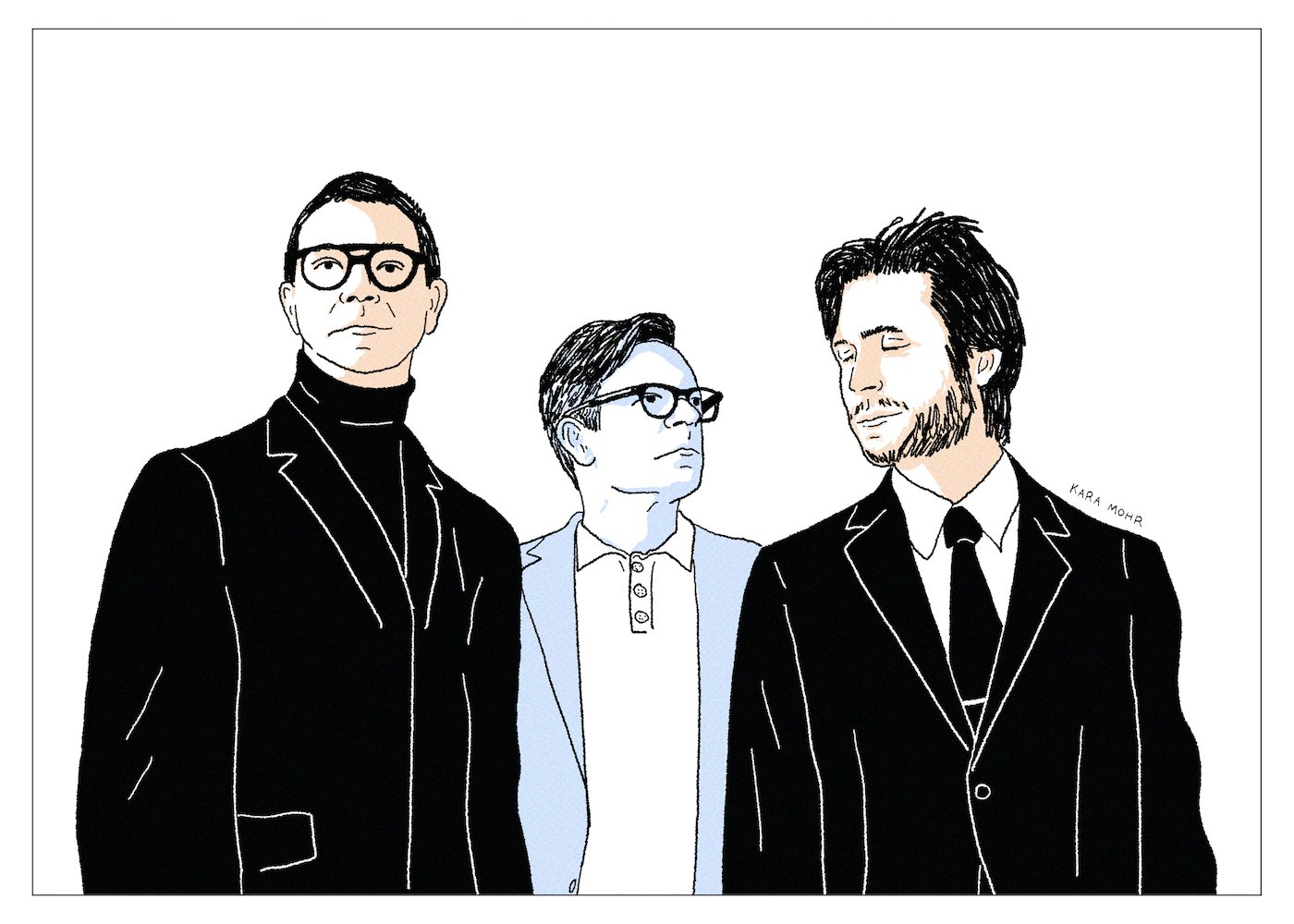

Interpol “The Other Side of Make-Believe”

Whereas most of those Williamsburg by way of Lower East Side bands of the early Aughts balanced post-collegiate pretense with drunken dude-ness, Interpol appeared to be all pretense. The suits. The black on black. The Factory Records of it all. Even before I heard a single note of their music, I was confused as to whether they were satire, or postmodern commentary, or totally earnest, or something I’d never encountered before. Eventually, though, I figured out that the Carlos and the Daniel and the Paul and the Sam I’d seen about town were identical to the ones who were on stage at Mercury Lounge. These were not actors. Those were not costumes. They were maybe not even uniforms. They were skins. And yet, back in 2002, every fiber in me was expecting the truth to eventually be revealed. The other black leather boot had to drop some day. No matter how great their debut album was. No matter how great their follow-up was. No matter how enduring the act, I was convinced that they’d trip up and be revealed as something fraudulent. Twenty years after “Turn on the Bright Lights,” though, I stopped waiting for the backlash.

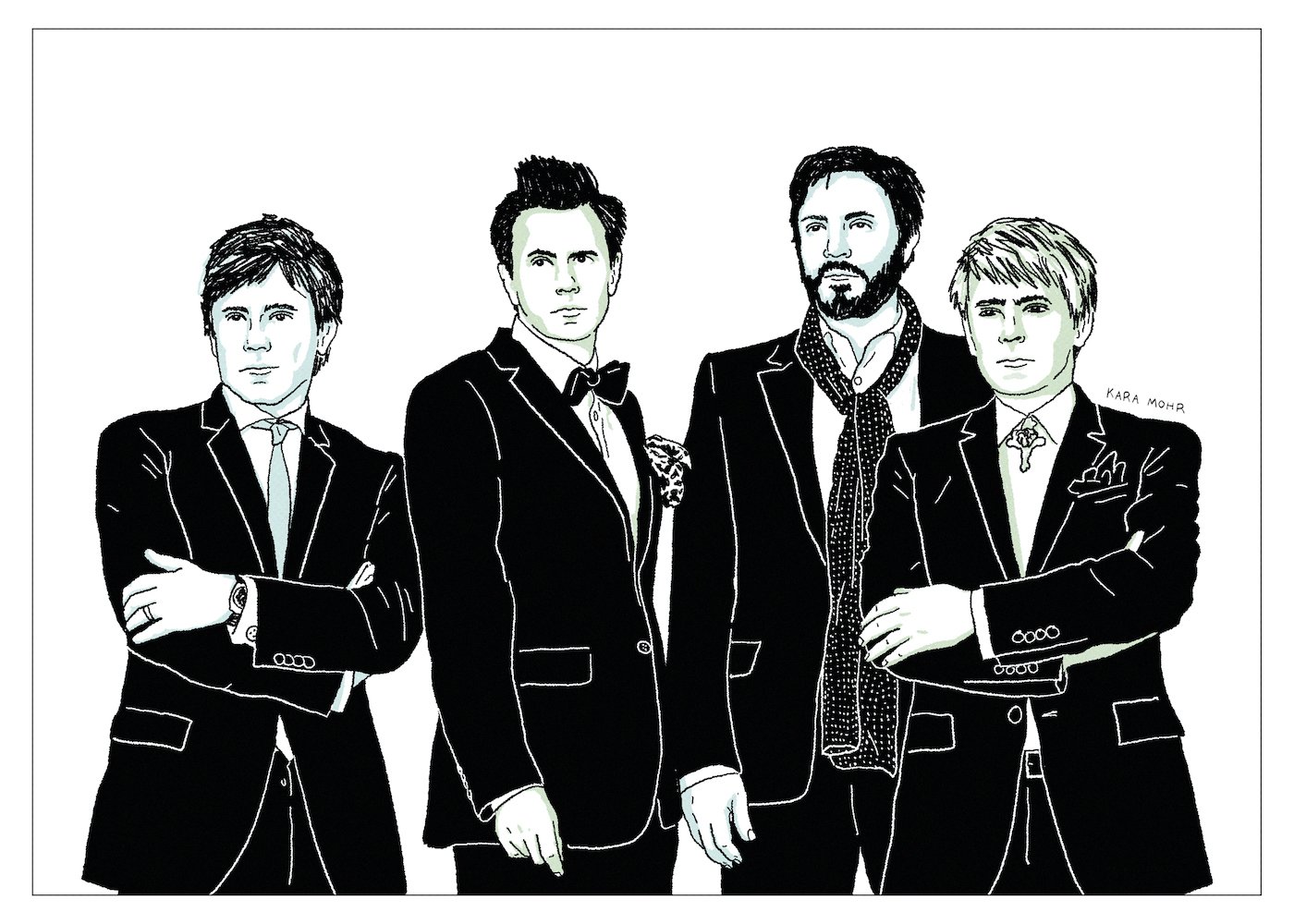

Duran Duran “All You Need Is Now”

By the time Duran Duran tired of their plight as Tiger Beat cover boys, it was too late. They would never be Chic meets Roxy Music, with a dash of The Sex Pistols. The corner of the world that they dreamed of had been claimed by New Order, The Cure and The Smiths. They were doomed to be Pop stars. And they could not tolerate it. After half a decade of fame, fortune, drink, drugs, and screaming girls, they splintered, and then buckled. And they’ve spent roughly the last forty years trying to put things back together — carefully toeing the line between looking back and looking forward. Their efforts included a forgettable covers album, a reunion of The Fab Five and a collaboration with Timbaland. But nothing worked. It increasingly seemed that Duran Duran would be remembered as one of the greatest Pop bands from the greatest moment in the history of Pop — and nothing more. Until, one day, Mark Ronson dared to wonder: “What if that moment returned?” Or rather, “What if we could recreate it? What if, thirty years later, we made the follow-up to “Rio?”

Ric Ocasek “Nexterday”

Ric Ocasek’s life after The Cars included a series of charming, lower stakes solo albums in between gigs as a “record guy.” For most of the 90s, he was a talent scout for Elektra Records and an elite producer for hire. But with Weezer’s “Blue Album,” Ocasek graduated from producer to “super-producer” — which meant he could do whatever he wanted, including making albums for Le Tigre and Brazilian Girls. It also meant that he could write poetry and paint and be the husband of a supermodel. He trimmed the New Wave mullet an inch or two, and maybe he added some lines to his face, but he still hid under the shades and bangs. He still wore oversized tops, buttoned all the way up. And he still had that odd earring dangling. In contrast, by 2005, Blondie was a nostalgia act. David Byrne was more high art than Pop. Sting made listless world music. And Duran Duran survived through the wonders of modern medicine. But Ric Ocasek, it seemed, had won. He’d done what Joey Ramone and Tom Verlaine never could -- stay weird and thrive. All of which makes his final solo album, “Nexterday,” hard to explain.

Imperial Teen “Feel the Sound”

By any reasonable standard, they never should have survived. All of those nineties “Buzz Bin” bands are gone. Fastball. Gone. Harvey Danger. Gone. Semisonic. Technically not gone but also gone. Marcy Playground. Either buried deep or gone. But Imperial Teen — the gender equitable, semi-queer group, who that sounded like ABBA if they’d swallowed The Pixies and who had that guy from Faith No More — kept going. Even after their first can’t miss single somehow missed. Even after they moved away and got other jobs and had kids. Even after their record sales dwindled. Even then, they’d get back together and make near perfect records full of bratty swagger, three part harmonies and hooks for miles. They’re the secretly Pop band who refused to get popular but also the Twee Indie act who never cowered. Which makes them a minor miracle.