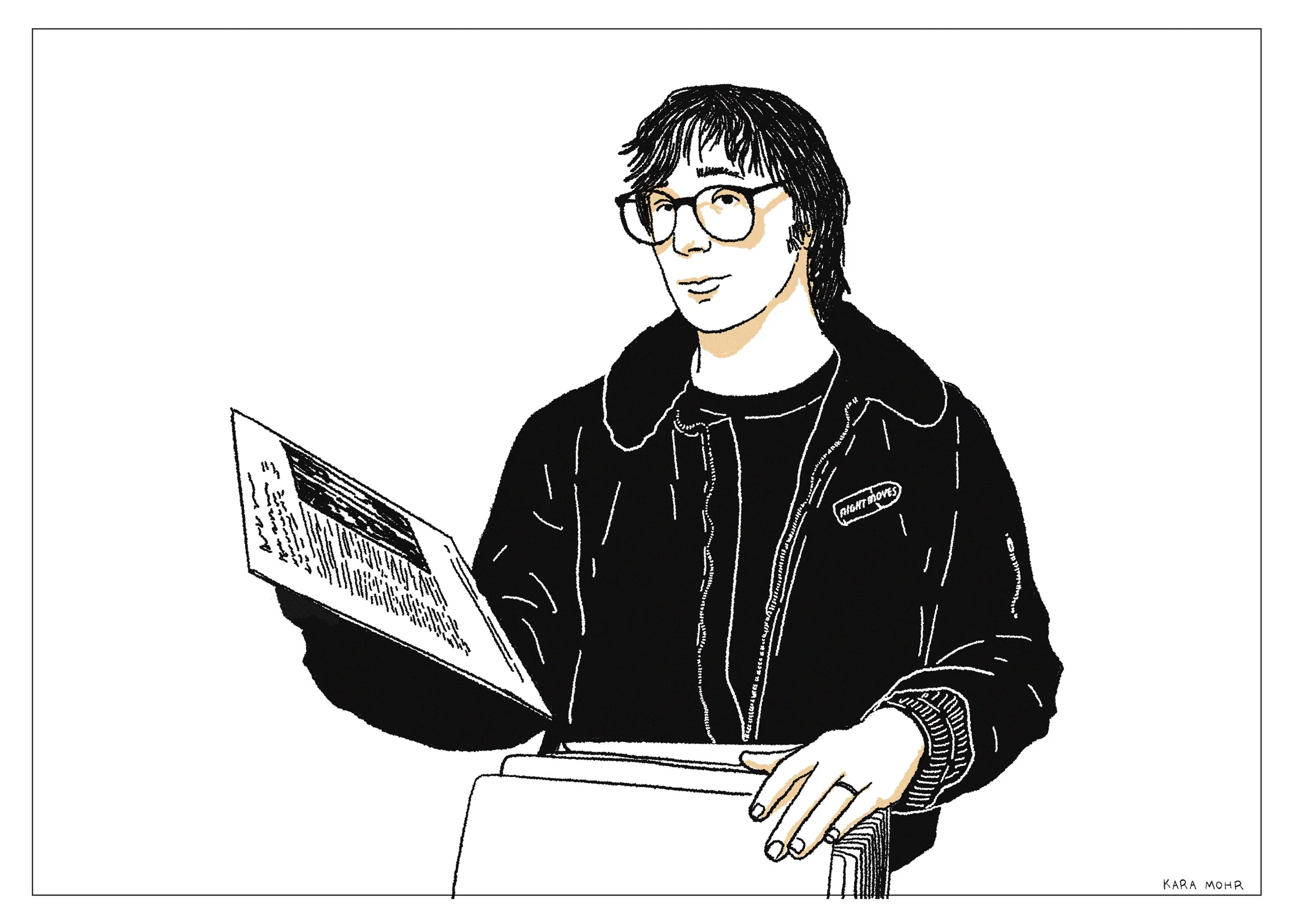

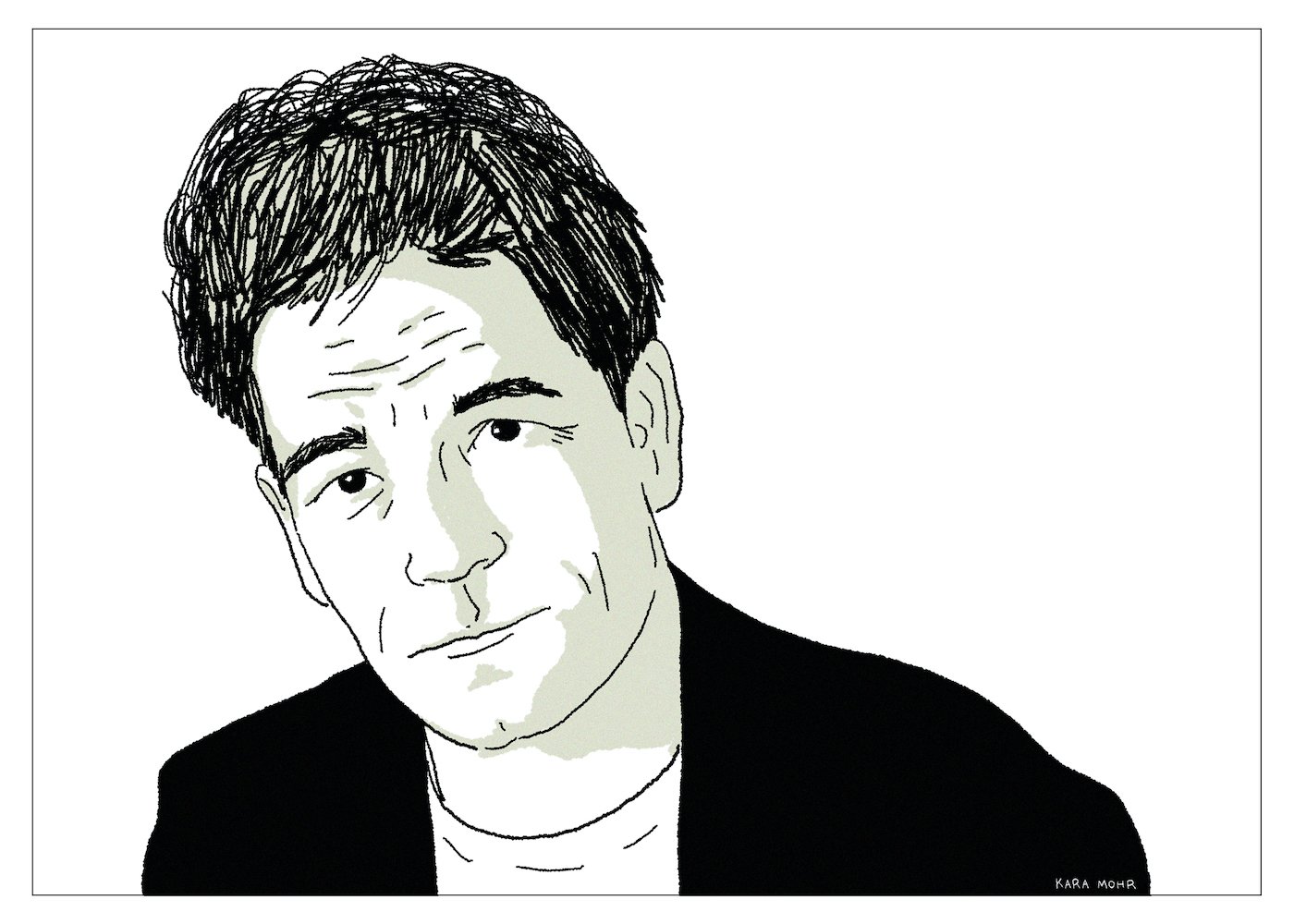

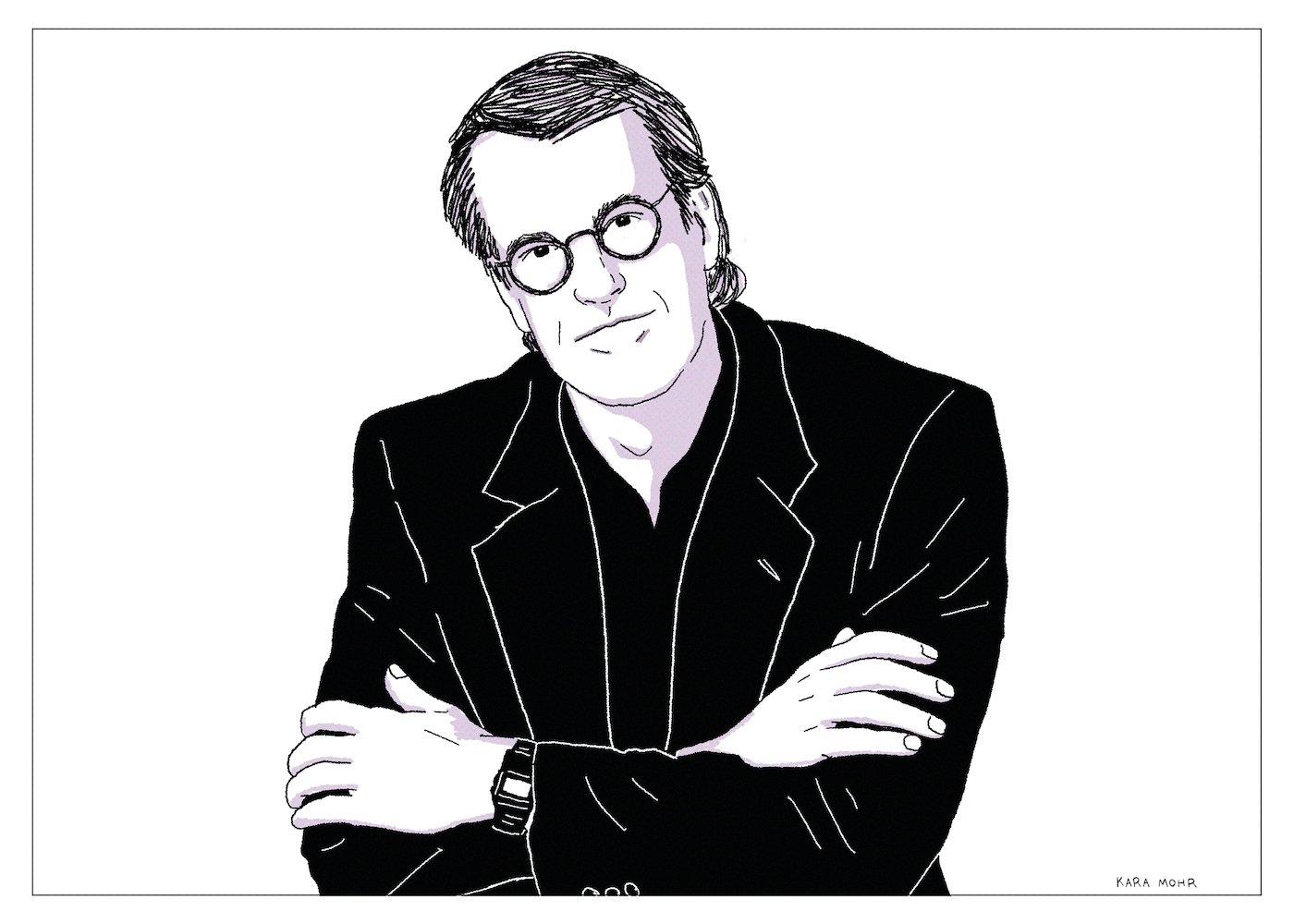

Robert Christgau “The Last Critic”

In the Fall of 1984, weeks after being dumfounded by my first encounter with “Bohemian Rhapsody,” I found myself at Tower Records with twenty dollars burning a hole in my pocket. And that’s where I found it—perched high atop Tower’s small but nevertheless intimidating (to a ten year old) collection of books I saw “Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies.” Intrigued, I took it off the shelf and made a bee line for “Q,” where I located a short, quizzical and mesmerizing summation of “A Night at the Opera” by Queen. There it was. 85 words and a terse letter grade: B-. It was everything I needed to know and also confirmation that I knew nothing at all. But most importantly, it was the promise that somebody, somewhere, somehow could help me figure it all out. And apparently that man’s name was Robert Christgau.

Dwight Evans “The Unfathomable Dewey”

When folks talk about the 1975 Red Sox, they frequently talk about Lynn and Rice, and more frequently talk about Carlton Fisk and “Game Six.” But what almost nobody mentions is that Dwight Evans, their great glove/some bat right fielder, notched 5.1 WAR that year. By comparison, Jim Rice had 3.0 and Pudge Fisk had 3.2. On a pennant winning club that included Yaz, Lynn, Rice, Pudge, El Tiante and Spaceman, and who nearly bested The Big Red Machine, Dewey was the other young kid. Which is kind of the story of Dewey’s career—always a groomsman but never the groom, except for those eight seasons when he was actually the best man or those four when he was actually the groom.

The Clean “Mister Pop”

In the second half of their third act, The Clean seemed increasingly disinterested in both their legacy and their future. Their first three albums—“Vehicle,” “Modern Rock” and “Unknown Country”—did not suffer from from this malaise. But “Getaway,” their fourth, was a minor backslide. And then came “Mister Pop,” their fifth and (now) final release, which sounded less like an album and more like a collection of lightly polished demos. For many years “Mister Pop” felt like a footnote in the band’s tiny but seismic discography. However, by 2023, after the death of Hamish Kilgour, it felt like a swan song.

Bad Company “Here Comes Trouble”

In 1992, a decade after they’d traded their sublimely gifted lead singer (Paul Rodgers) for Ted Nugent’s former frontman (Brian Howe), Bad Company were in the waning hours of their second sunset. But somehow, three decades later, I find myself more than a little impressed with their final salvo. It's not so much that “Here Comes Trouble” is exceptional—it’s absolutely not. But rather that it is exceptionally good. It is both what I expected—professional, middle of the road, twenty percent softer than Hard Rock—and also a complete surprise—melodic, pleasurable, immaculately recorded songs that locate the exact midpoint between Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is” & “Jukebox Hero.”

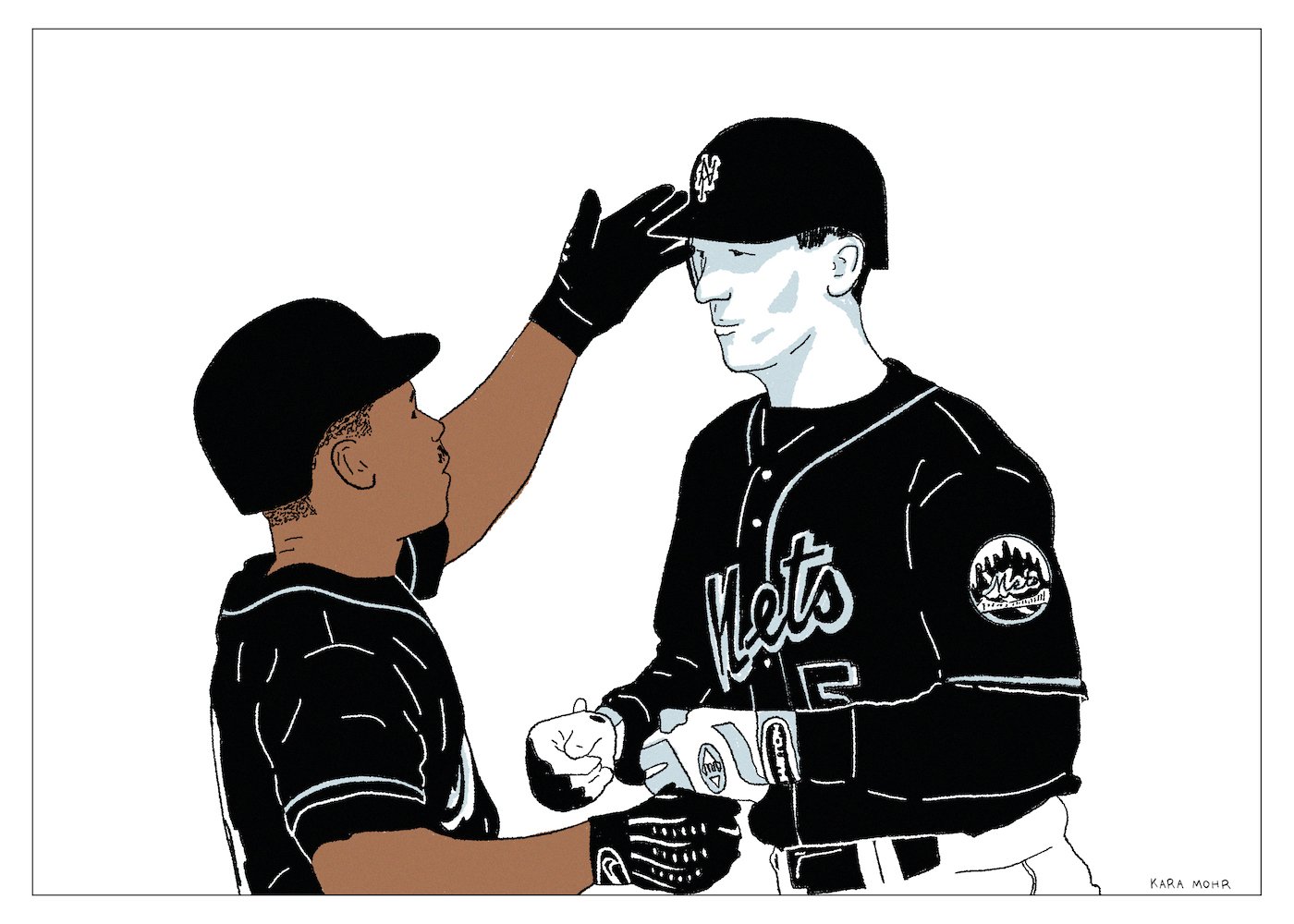

Jeff Kent “The Enemy of Your Enemy”

In the winter of 1996, having already been traded twice in his young career, Jeff Kent was traded again—this time to The San Francisco Giants, where he both blossomed and soured. Alongside the Barry Bonds—the slugging, running, intentionally walking, video game centerpiece of the club—Kent helped lead the team to six straight winning seasons. Moreover, while in The Bay, Kent averaged thirty home runs with a hundred RBIs and a .300 average year in and out. And yet, to this day, Jeff Kent is perhaps less remembered for his offensive prowess than as Barry Bonds’ most offensive antagonist.

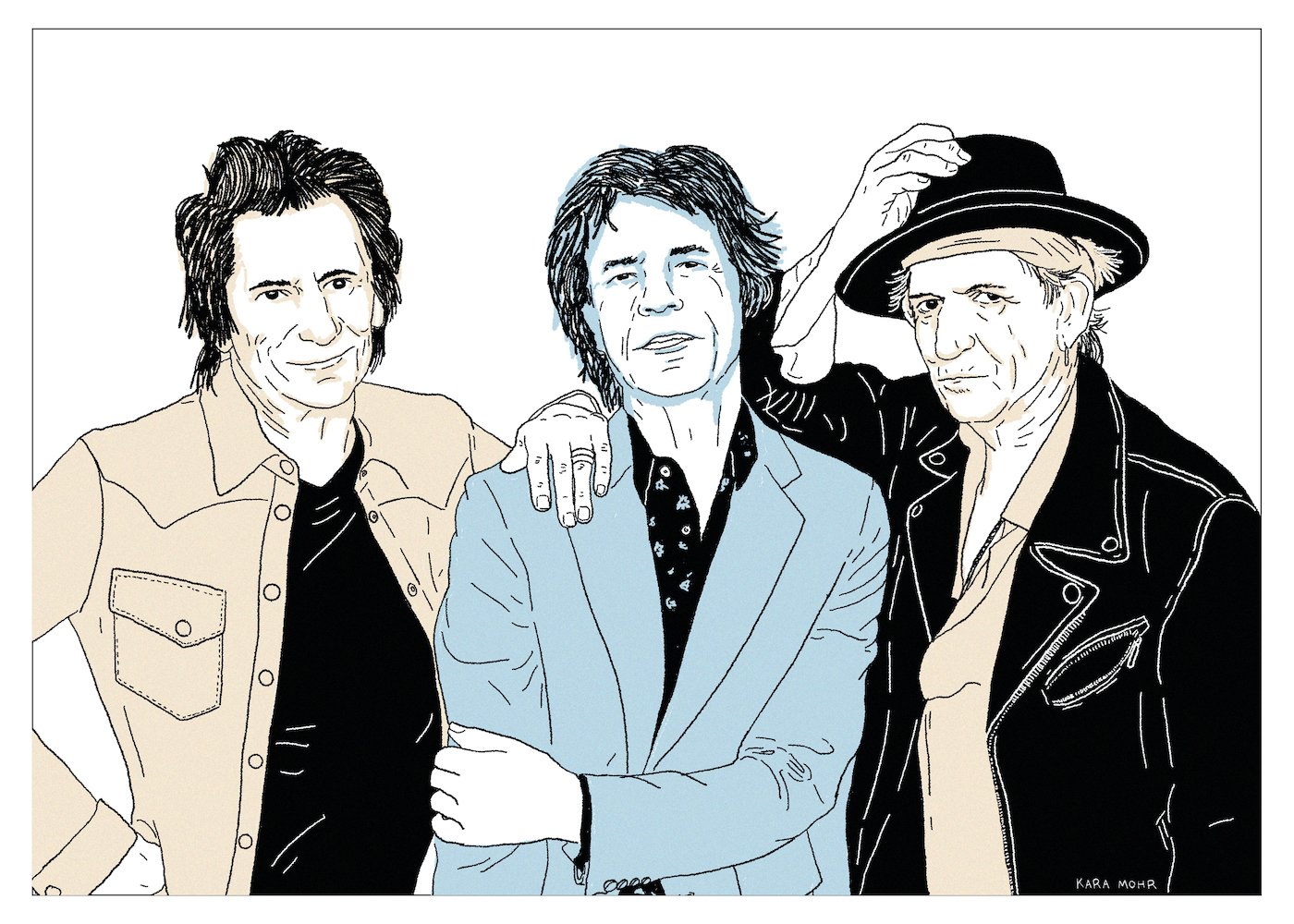

The Rolling Stones “Hackney Diamonds”

ChatGPT—can you make a song that sounds like “Start Me Up,” but a little faster? OK, thanks. ChatGPT—can you make it a little more Pop? ChatGPT—a little faster please. Can you also make Mick sound like he’s thirty? No—too young. How about forty-five? OK—great. Now — can bring the vocals up & make the beat snap more? Can you isolate Keith’s guitar & raise it up a bit? And can you clip all the highs & lows from the mix? OK, perfect. Now ChatGPT—can you find something Country-ish from “Some Girls” & do the same thing? Then just keep going & let know when you’re finished. Thank you ChatGPT.

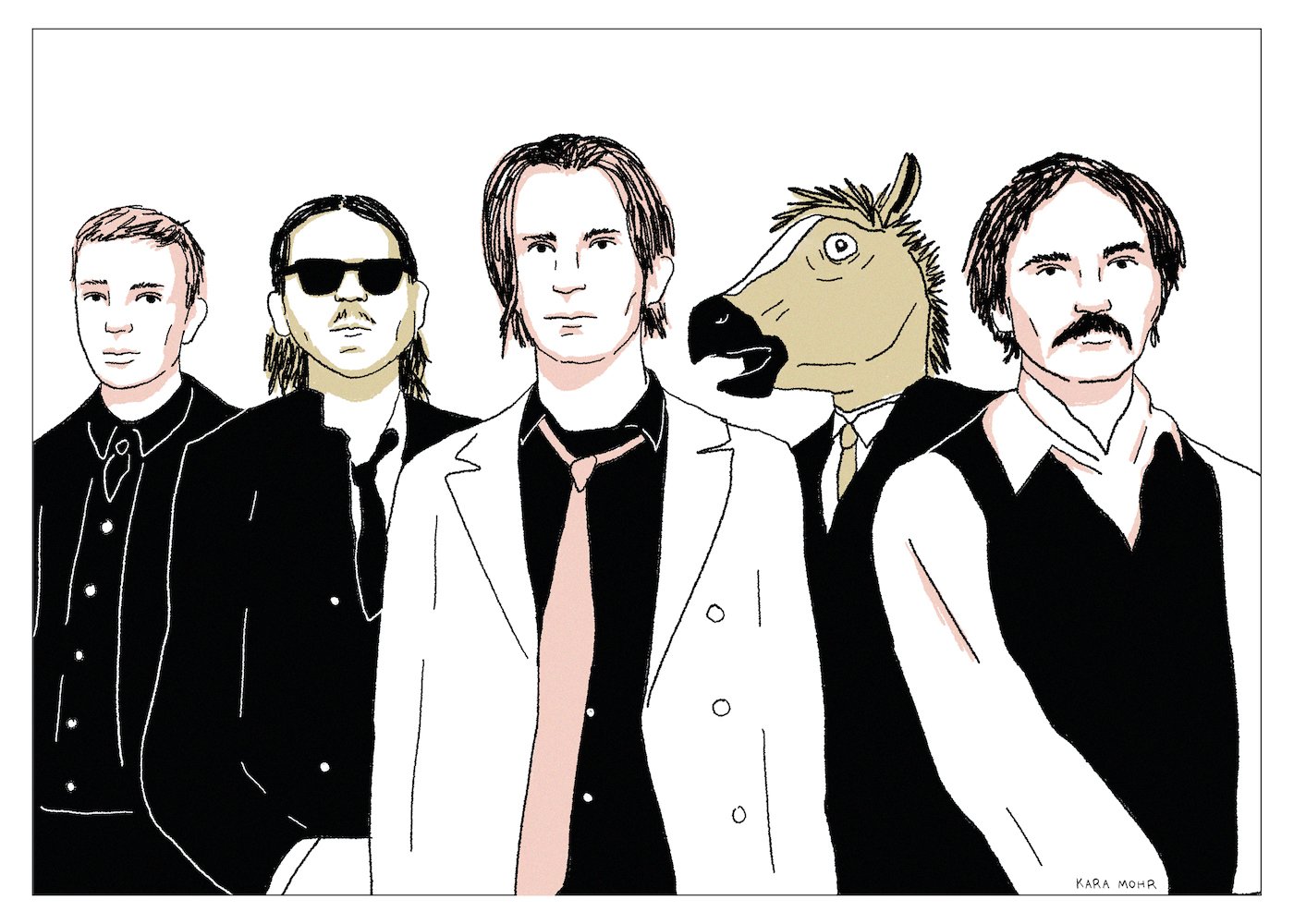

The Black Heart Procession “Six”

If Hot Snakes embodied the face of post-Hardcore San Diego—molten & unrelenting—Black Heart were the underside—dusky & longing. Pall Jenkins & Tobias Nathaniel made aching nocturnes—hardly Rock songs—better suited for Victorian lockets than iPods or CDs. But after five albums of unopened letters about unrequited loves, “Six” made the turn from noirish black to Hot Topic black. You could read it in the track listing—titles like “Drugs,” “Heaven & Hell” & “Suicide”—and you could see it in the cover design—pagan crosses & “SIX SIX SIX” scrawl. All signs indicated that the carnage was more B-movie horror than emotional distress—that the aesthetic feature had become a shticky bug.

John Olerud “Un-unforgettable”

There are several permutations of the “Rickey and Oly” story, including hysterically far flung versions wherein the latter is basically Jesus. But, regardless of the version, the fundamental premise remains consistent. And as short stories go, this one is a formal marvel. It’s got a great setup and an even better kicker. It’s succinct and hysterically funny. It confirms our assumptions that Rickey Henderson was both extremely perceptive and completely oblivious — that he was operating on a different plane and dimension from “normal” stars. But moreover, it acknowledged the thing that every baseball fan knew to be true but which none would say out loud: that John Olerud is un-unforgettable.

Blue Öyster Cult “Imaginos”

“Imaginos” is not really a Blue Öyster Cult album. Yes — it features the same five men who played on their beloved Seventies albums. But no — those five men did not write, play or record the album together. The name “Blue Öyster Cult” appears in name only, as a last ditch effort to see if the parties involved could recoup any of the significant cost sunk by their former drummer, Albert Bouchard. And yet, in a strange way, “Imaginos” is also the most Blue Öyster Cult album in that it was born from the band’s source material. While frequently indecipherable, “Imaginos” is oddly important in that its concept not only predated Blue Öyster Cult, but actually invented Blue Öyster Cult.

Deep Purple “The House of Blue Light”

In “This is Spinal Tap,” documentarian Marty Di Bergi reminds the band that their 1980 album “Shark Sandwich” had once famously received a review which read simply: “Shit Sandwich.” But in (cinematic) fact Spinal Tap were always loathed by the critics and “Shark Sandwich,” which featured “Sex Farm” and “No Place Like Nowhere,” was actually something of a return to form. Like “Shark Sandwich,” Deep Purple’s “Perfect Strangers” did not fare well with the mainstream press. In 1985, Rolling Stone printed a two star review that read like a one star review. Nevertheless, and like Spinal Tap’s late career hit, “Perfect Strangers” thrived commercially. But, if “Perfect Strangers” was Deep Purple’s “Shark Sandwich,” it follows that “The House of Blue Light” was their “Smell the Glove,” an ill-fated document of disunion that revealed a band spiraling into mid-life crisis.

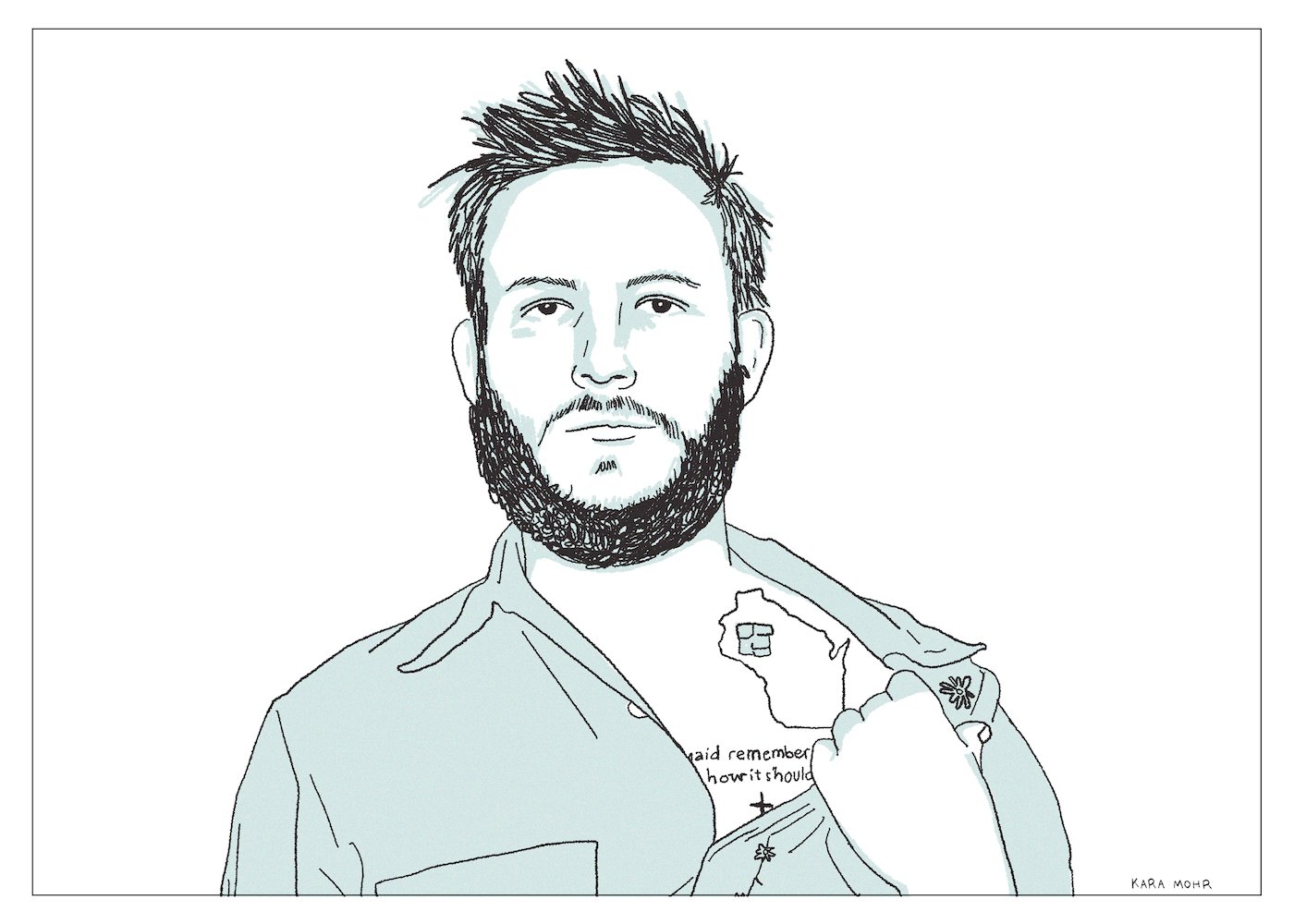

Magnolia Electric Co. “Josephine”

By the time of “Josephine’s” release, Jason Molina was almost completely out of the picture. Those who were still following along understood that while Molina might always be the patron saint of Secretly Canadian Records, Justin Vernon was the prodigal son of the Secretly Canadian Empire. And that while Jason Isbell might have looked upon Molina with reverence, Americana’s new “It Boy” had bested his predecessor in the popularity contest. In 2009 Molina was neither as new as Vernon nor as sociable as Isbell. Meanwhile, reviews of “Josephine” were ambivalent and sales were middling. In the end, Molina’s return proved to be shaky and short lived. Soon after “Josephine” arrived, he cancelled tour plans for “health issues.” And over the next three years, aside from the occasional rumor or warning flare, Jason Molina was basically a living ghost.

Black Sabbath “13”

Once upon a time, Black Sabbath were considered musical troglodytes — dumb, artless wankers, shunned by the cultural cognoscenti. Years later, even after many fans and some critics came around, they were still treated like drunk, possibly murderous threats. It was not until recently, long after Ozzy left, after Ronnie left, after most of the world had reconsidered them, that Sabbath settled into the realm of quaint, rich celebrity. They came to signify the excess and darkness of Seventies Hard Rock and the eventual convalescence from said excess and darkness. By 2013, Ozzy Osbourne was unimaginably wealthy. He was a reality TV star. He was a doddering, comical old man. And yet, despite the passage of time, despite the reputational rehab and despite Ozzy’s defanging, “13” is not funny — not for a single moment.

The Olivia Tremor Control “Garden of Light” and “The Same Place”

Whereas Bill Doss was a hard working free spirit, Will Cullen Hart was more of a boundless tinkerer. Doss’ songs have an easy air about them — they feel well-crafted but also kind of effortless. Hart’s songs, on the other hand, sound unlike anything or anyone else. If The Olivia Tremor Control were a miracle, Hart was the miracle worker. And of the many miracles he performed, none were more miraculous than the ones he manifested on November 29, 2024. That day, at the age of fifty-three, he bequeathed us “Garden of Light” and “The Same Place.” The surprise of these two gifts — the first new music from OTC in fifteen years — was all the more mind boggling, though, when you consider what immediately preceded them. Just a few hours earlier, Will Cullen Hart had passed away from natural causes.

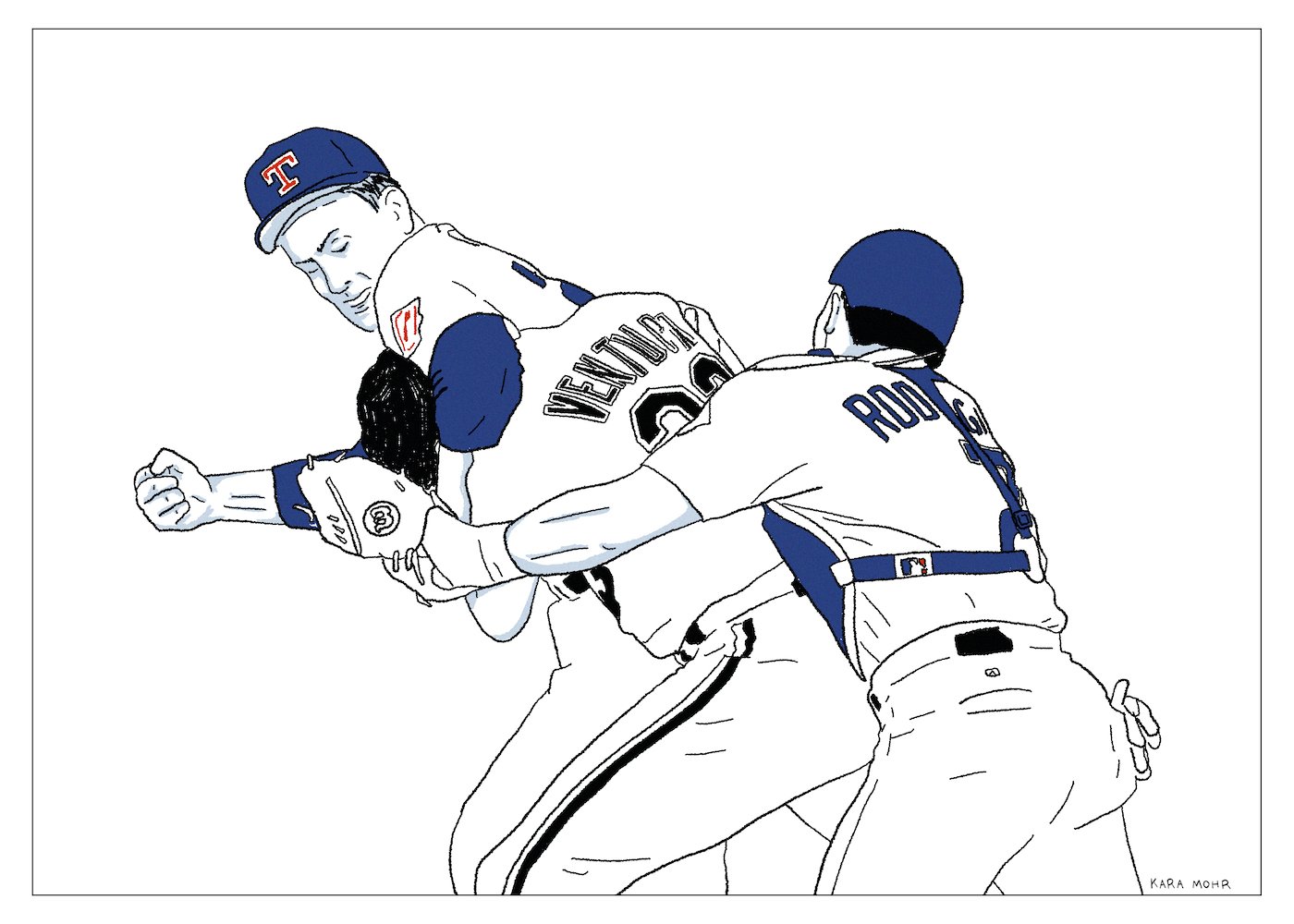

Robin Ventura “The Misremembrance”

His “grand slam single” during the 2000 NLCS would have been the most memorable event from almost any other player’s career. So would have the two grand slam game or the two grand slam double header. So would all those gold gloves. And that’s not to mention anything of the fifty-eight game collegiate hitting streak. Any one of those feats would have been a career hallmark for most ballplayers. But not so in the case of Robin Ventura who, on August 4, 1993, dared to charge the mound inhabited by one Nolan Ryan.

Bon Iver “Sable”

As Bon Iver evolved from loner in the shack to experimental Jam band, Justin Vernon became more diffuse — and more opaque. His voice was everywhere, but his songs were impossible to decipher. His career was simultaneously safe and unpredictable. He was Indie Rock canon verging on Pop canon, but one never knew when or if the next album would come. And one never knew what it might sound like — except that it wouldn’t sound like “For Emma, Forever Ago.” Justin Vernon was not going back.

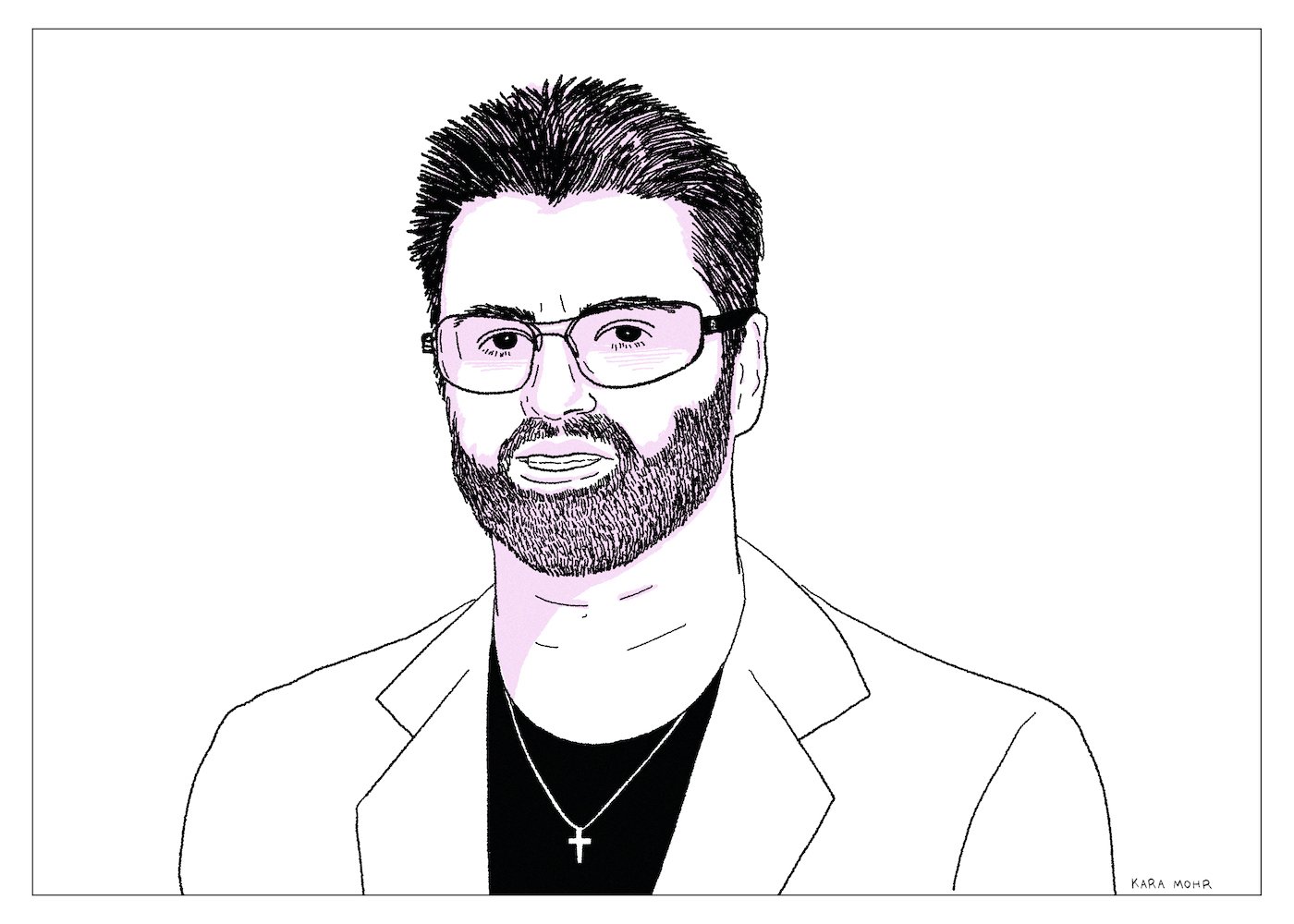

George Michael “Patience”

Eight years removed from his last album of originals — after a very public arrest, after the death of his mother and his partner — George released what would become his swan song. Having lost most of his U.S. fanbase, “Patience” was less a triumphant return and much more an album for aging diehards. Like all George Michael albums, it was an extremely personal one. But, it was also a radically honest album. Prince employed characters and double entendres. Michael Jackson used masks. And Madonna had her costumes. But there was always a sense that George was telling the absolute truth. That what we were hearing was not a “version of George Michael,” but the man himself.

Huey Lewis and The News “Plan B”

The Nineties were a fallow period for Huey Lewis and The News. Following a decade wherein they released nine albums, the band mustered just two over the next ten years. His platinum-selling, chart-topping days were a thing of the past, but his transition from Heartland New Wave to aging Mom-and-Dad-core was both graceful and inevitable. In some ways it made much less sense that Huey Lewis was ever a bonafide Pop star and more sense that he was a charming screen presence who occasionally put out R&B albums. By 2001, at the age of fifty, Huey had finally achieved his pop culture destiny, settling into his rightful place as Bruce Willis’ less theatrically — but much more musically talented — cousin.

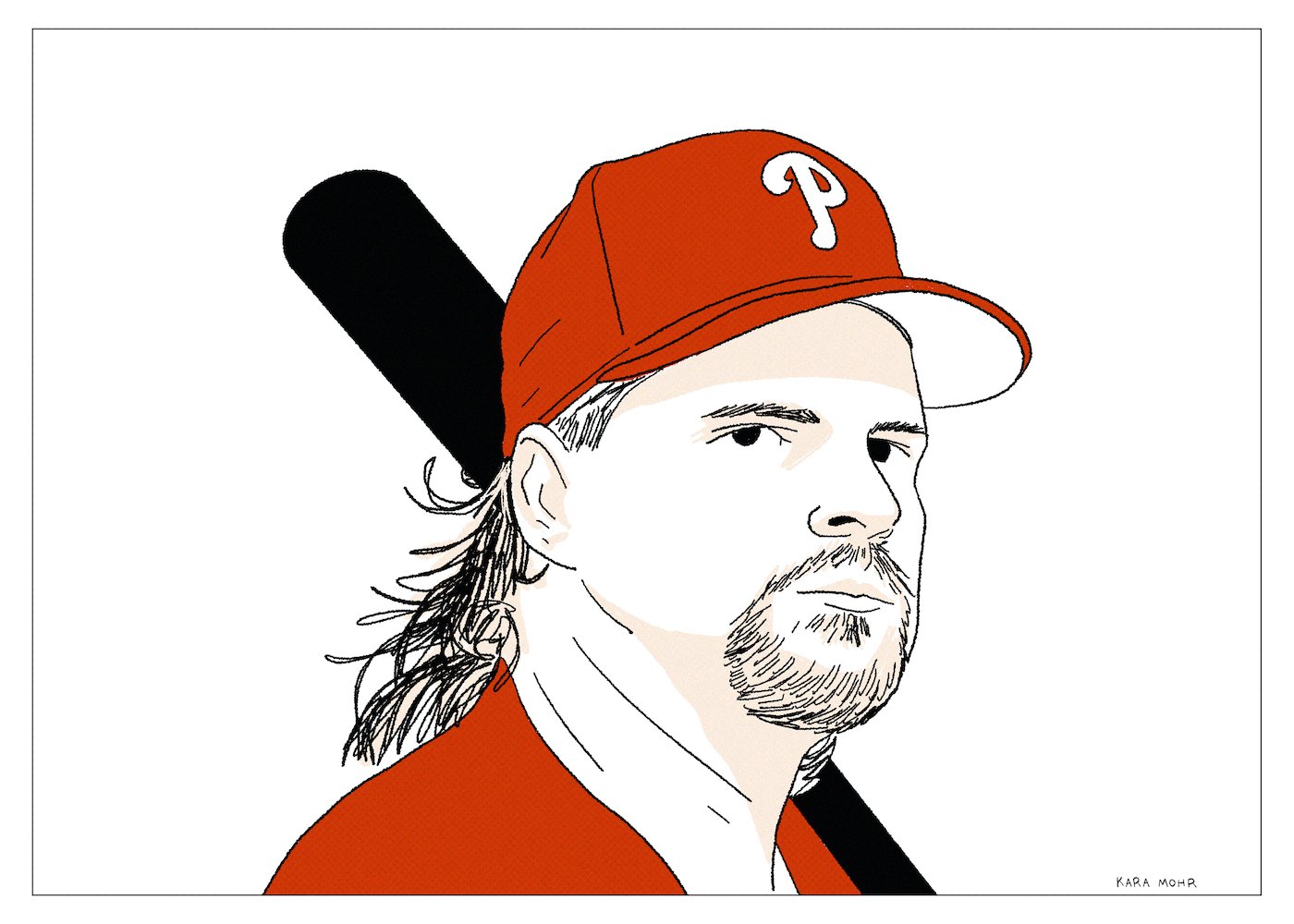

John Kruk “The Mullet Gives You Permission”

In 1972, President Richard Nixon made a diplomatic visit to mainland China where he finally, formally recognized the Communist government. Conventional wisdom suggested that only Richard Nixon, with his unimpeachable anti-communist bona fides, could have made such a conciliatory move. In the case of Nixon and China, for the truth to be heard, a very specific messenger was required. Twenty one years later, baseball got its Nixon and China moment when John Kruk faced Randy Johnson in the third-inning of the 1993 All-Star Game. During that legendary, if swift, at bat, Kruk revealed a truth that had been suppressed for years and which he alone could effectively convey: baseball is terrifying.

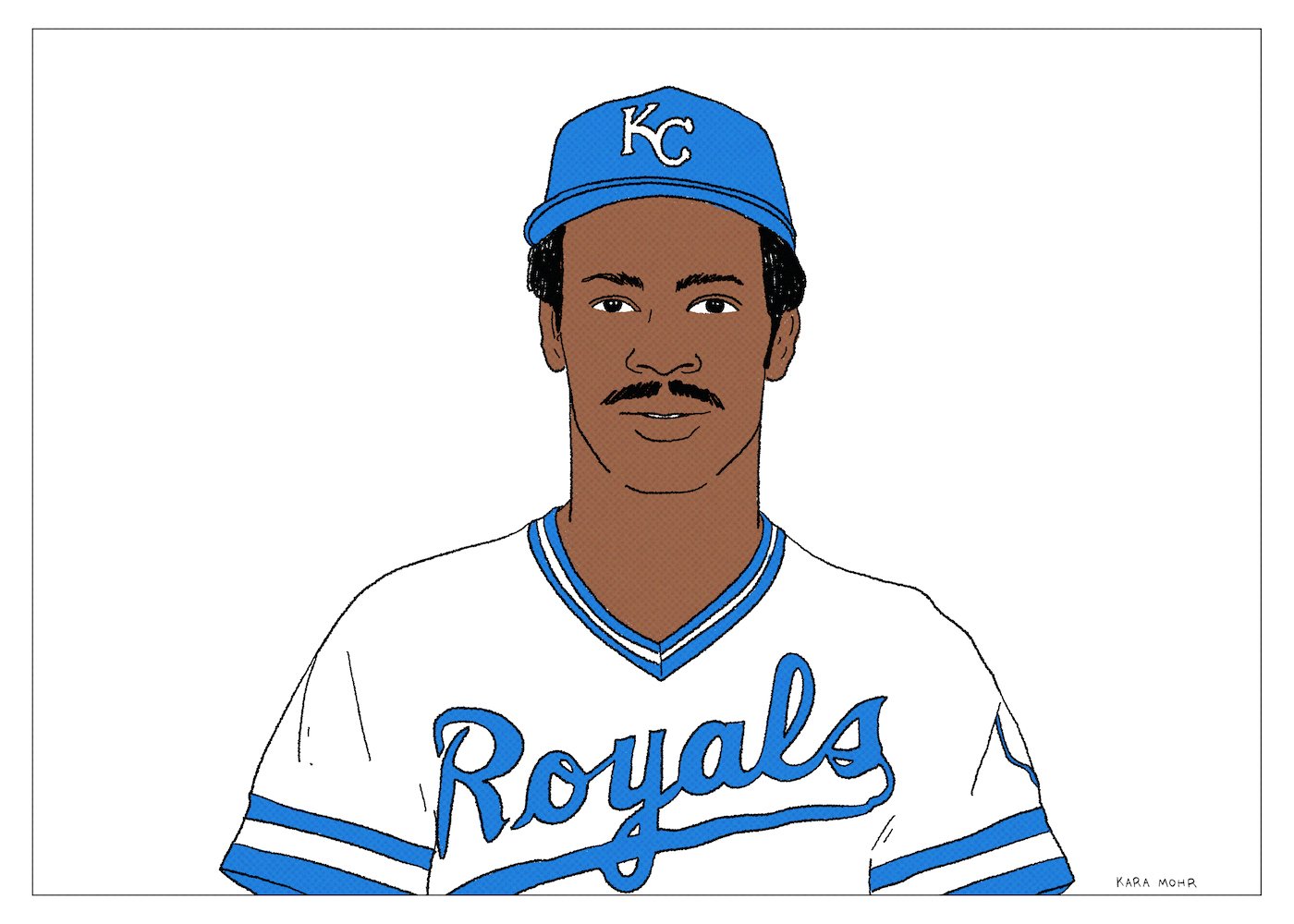

Willie Wilson “Speed Kills”

It is a cliche to suggest that, in life, your greatest blessing becomes your curse — that your feature becomes your bug. But in the case of Willie Wilson that seems especially true. So gifted, so fast and so strong, Willie could have been an All Star in most any sport. But the sport he chose was the one which least suited his particular genius. There’s a certain tragedy in knowing that you can surely do things that no one else in the game can do, but at the same time knowing that those things only matter so much in your chosen game.

John Tesh “Live at Red Rocks”

Recorded in the summer of 1994, “Live at Red Rocks” first aired on PBS in the Spring of 1995 and hit stores just a few months later. In the thirty plus years since, it’s become synonymous with both “Nineties New Age” and “PBS fundraising.” Which is to say that it is simultaneously elaborate (not minimalist or tranquil) and cheap (free with donation). As an album of recorded music, it is almost farcical. But as a concert movie, it's positively gripping. For one windy night, against an breathtaking backdrop, accompanied by the Colorado Symphony Orchestra, and dressed in a three piece purple suit, John Tesh — the co-host of "Entertainment Tonight" — thrilled a rapt audience of dedicated philanthropists and Olympic gymnastic enthusiasts.