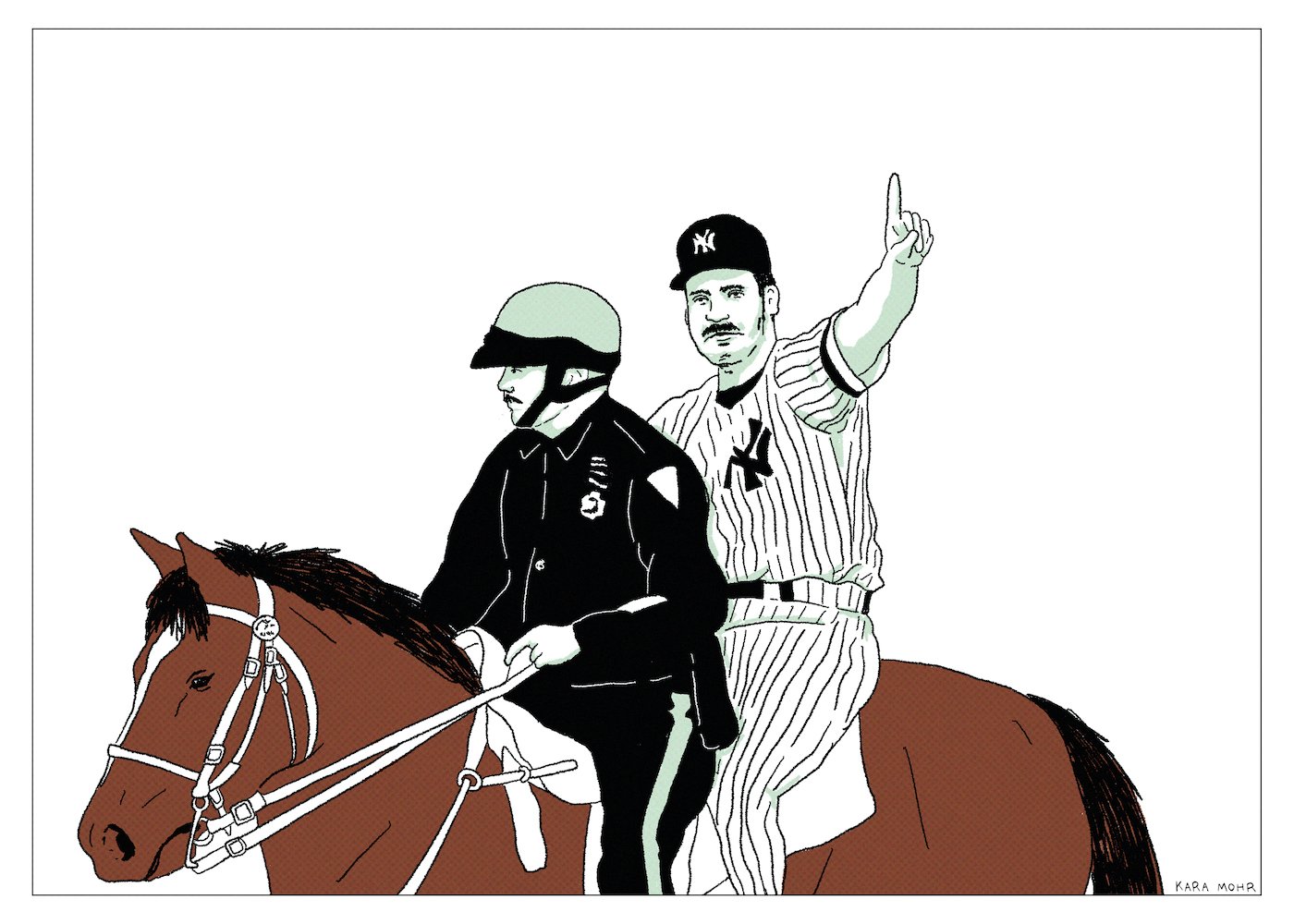

Wade Boggs “The Visible Man”

Wade Boggs told the world many stories. That he twice saved his own life by turning invisible. That he once drank 107 beers on a cross-country flight. That his baseball hitting prowess was aided by poultry consumption. That he was a New York Yankee. But, what was the truth? Was he delusional? Was he magical? Was he just a neurotic with astounding hand-eye coordination? One thing is certain: it must have been hard work to become Wade Boggs. Willie Mays and Joe DiMaggio were beloved for making baseball look so easy. Wade Boggs, on the other hand, had to hit Dave Stieb sliders and check his watch to see if he could end practice on a 7 and trace Hebrew good luck charms in the dirt and find missing pennies in the dirt near The Green Monster. He did that, every game of every year, while also hitting .330.

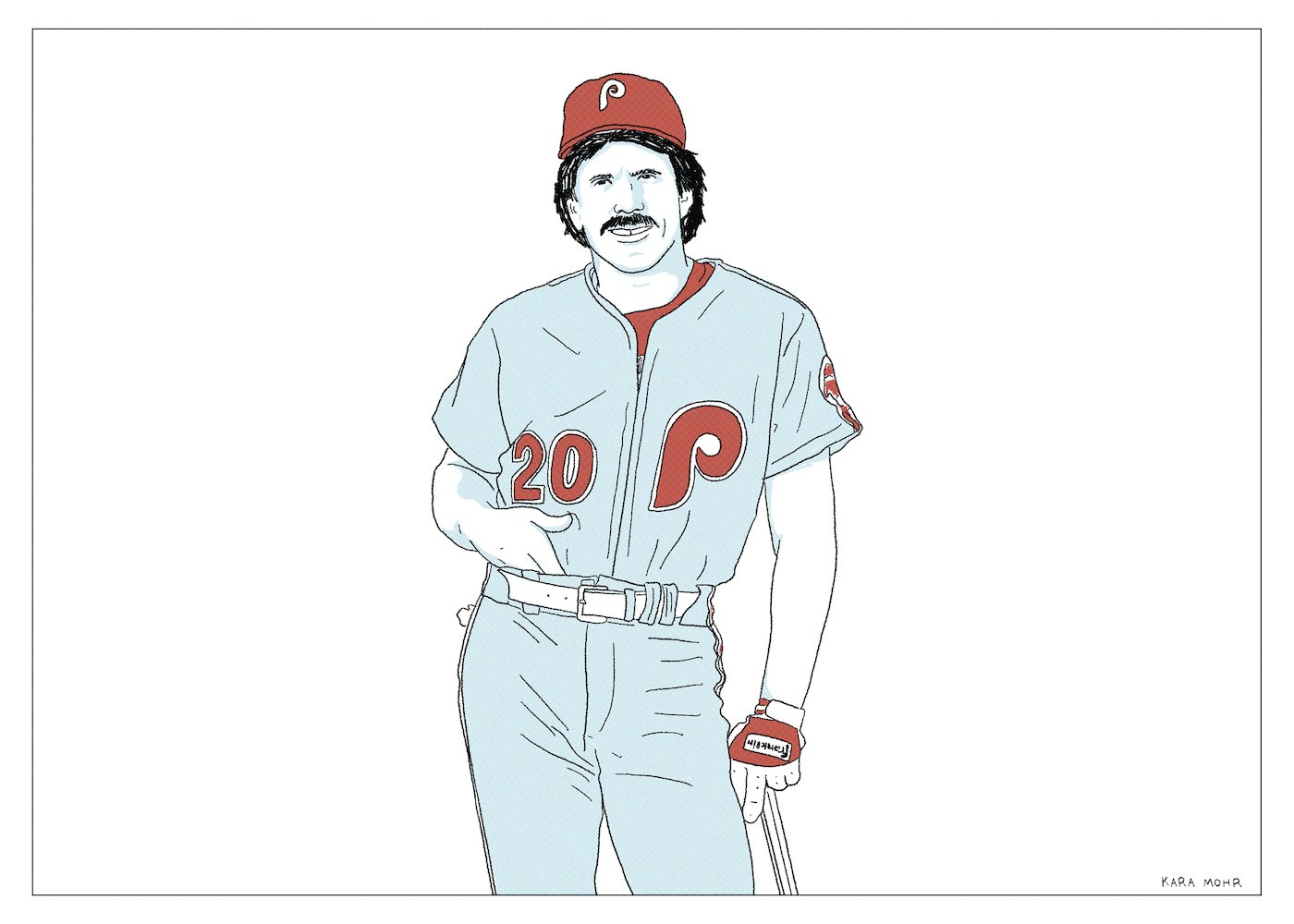

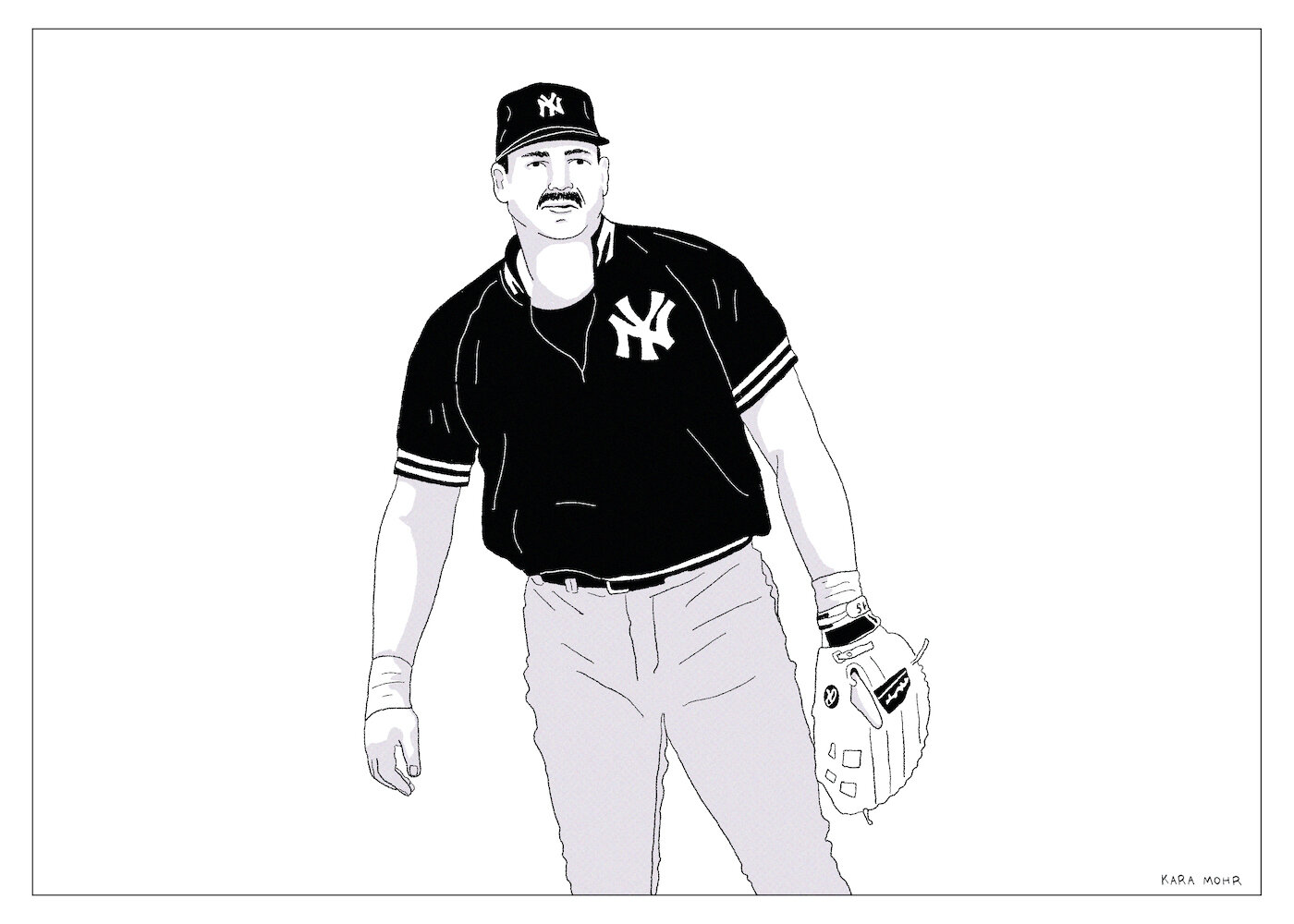

Mike Schmidt “Two Very Bad Knees and a Dream”

Pete Rose was filthy. George Brett had hemorrhoids and a temper. Willie Stargell had a massive gut. Dave Parker and Keith Hernandez smoked in the dugout. Rickey Henderson was from another planet. Half the league was popping pills. And the other half was coked out. The joy of Willie Mays was replaced by the swagger of Reggie Jackson. The 1970s was a decade of lost innocence for major league baseball. The 1980s were perhaps weirder still. What had been a relatively staid game from 1920 through most of the 1960s was suddenly less predictable. In fact, it was becoming downright bizarre. Change was everywhere. Except, of course, at third base in Philadelphia, where Michael Jack Schmidt stood, permed and mustached, for nearly two decades.

Ichiro Suzuki “What Else Can I Do”

Like the magical Madrigal children from Disney’s “Encanto,” Ichrio Suzuki was only allowed to be one thing. In his case: the greatest hitter of singles. Just like Madrigals, however, his blessing was also his curse. As a child, when he wanted a day off from the incessant, metronomic process of becoming Ichiro, he just sat down in centerfield and refused to play. His father responded by whizzing baseballs at him. Later, when Nobuyuki Suzuki turned over the training of his son to high school coaches, he had one instruction: “No matter how good Ichiro is, don’t praise him. We have to make him spiritually strong.” In perhaps the most understated reflection on one’s childhood ever, Ichiro recalled, “It bordered on hazing and I suffered a lot.”

Albert Belle “Snapper”

He had a weird batting stance. He crouched right on top of the plate and then leaned in even further. At times, his head appeared to be firmly in the strike zone. When he got set, he did not budge. And, until the pitch was thrown, he cast a murderous gaze upon the pitcher. There is truly no better adjective for his expression. If somebody glared at me the way that Albert Belle glared at Greg Maddux in the 95 World Series, I would probably call the cops. To suggest that he was the best hitter of his era is defensible, but highly debatable. To claim that he was the angriest or most hateful batter, however, is not up for discussion.

Kevin Mitchell “All In”

Moments after The Clintons entered our lives, but right before PEDs consumed baseball, Kevin Mitchell was chasing immortality. By the All-Star Game, he was ahead of Babe Ruth’s home run pace. One night in April of 1989, he chased down a tailing Ozzie Smith line drive and caught it between the foul line and the wall — barehanded! Though I was not old enough to have seen Maris’ run at Ruth or Reggie’s run at Maris, I knew greatness when I saw it; even if it was sudden and unexpected and from a guy who was recently the fifteenth best player on the Mets. So, I responded in a way that felt beyond obvious to my eleven year old self: I emptied my non-existent bank account, forced my Dad to take me to the nearest baseball card convention and began to corner the market on Mitchell rookies. I was all in.

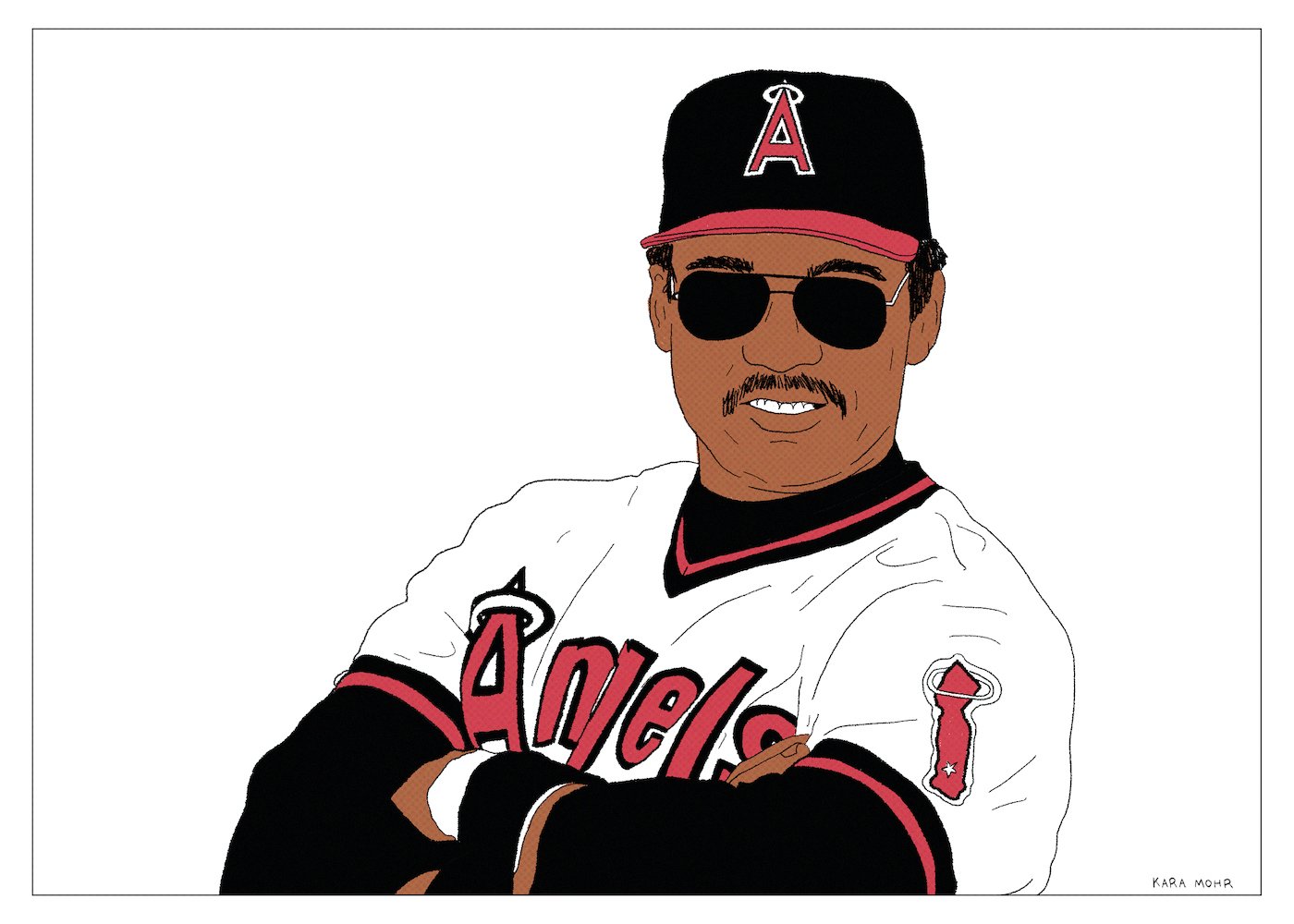

Reggie Jackson “Old Reggie”

In 1988, Reggie Jackson co-starred in “The Naked Gun,” where he attempted to assassinate Queen Elizabeth, only to be foiled by Enrico Palazzo. For younger generations, it is that Reggie — older, sillier, wearing prescription sunglasses — who they remember. But, not me. I was too young to remember Reggie, the young Oakland phenom. And I barely recall the magic of 1977. My Reggie was the superstar on a candy bar wrapper. At the plate, he appeared menacing and unpredictable — but still like a man. He wasn’t a bull, like Greg Luzinski, or a viking, like Gorman Thomas. Reggie just looked like a guy who wanted it way more. Who swung with more violence. Who tried harder. And who made it very easy to see how very hard it was to hit five hundred and sixty three home runs.

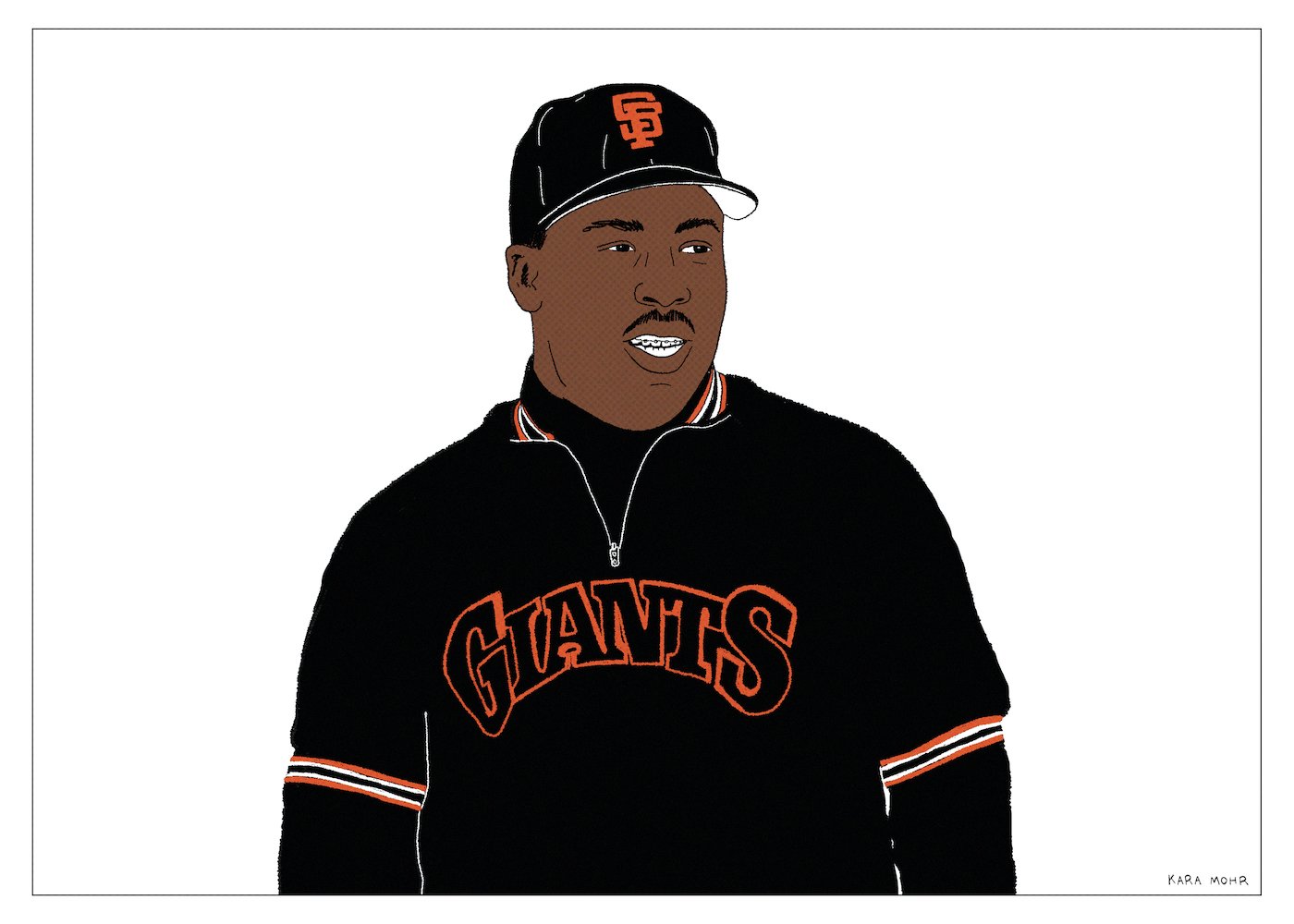

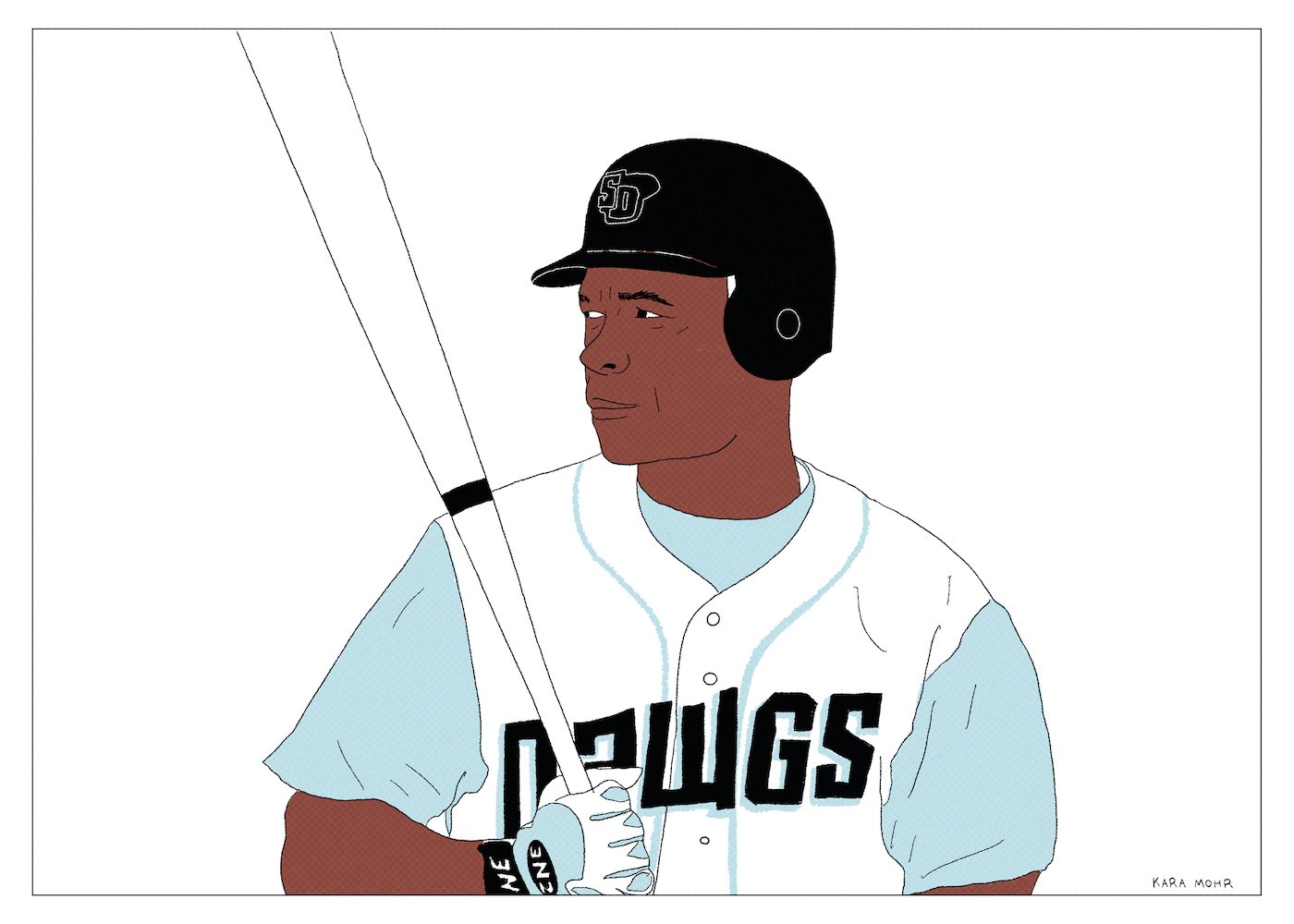

Rickey Henderson “The Greatest of All Time”

People (like me) lazily toss around adjectives like “incomparable” or “singular.” But there has never been a person so professionally atypical as Rickey Henderson. He made Steve Jobs and Henry Ford seem kind of average. He had more in common with Hermes or Spiderman than with Vince Coleman or Mookie Wilson. And, for twenty five seasons, he broke major league baseball. He wanted to play forever. He was certain that he could. But, in 2005, he was a San Diego Surf Dawg of the Golden Baseball League — where young men who will never make the Big Show went for a summer of fun and where former pros were put out to pasture.

Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker “Keystone Kids”

Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker played nearly two thousand major league games together, turning over a thousand double plays between shortstop and second base. Trammell is in the Hall of Fame and Whitaker — based both on the data and Trammell’s impassioned case — should probably be there as well. They bunked together in the Minors, arrived to a suffering franchise in 1978 and, eventually, delivered the Tigers a World Series title in 1984. They are each other’s indisputable, number one fans. Forty years after they first played catch, the Keystone Kids have come to signify that elusive, romantic thing that men of a certain age rarely discuss but constantly long for: friendship.

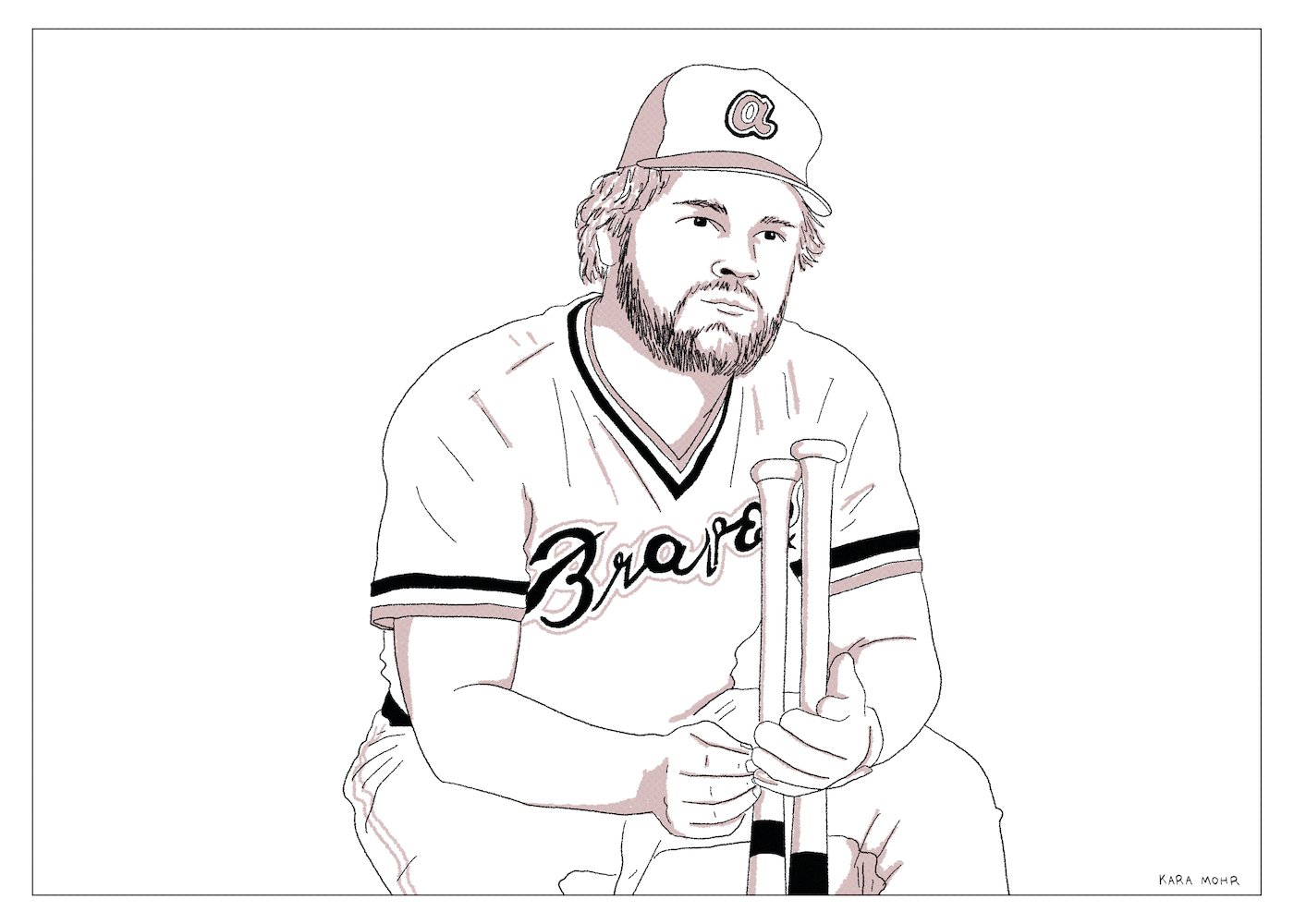

Bob Horner “Mr. Ho Mah”

Bob Horner never had career angst. He was born to use his hands and arms to strike objects with tremendous force. I suppose he could have been a great boxer, though that risks personal injury. Had he been born abroad, maybe he would be known today as the greatest cricket player of his generation. I guess he could have been the MVP of a building demolition outfit. Those were all possibilities. But when you’re born in Kansas in the late 1950s, and you look like the love child of Babe Ruth and Kenny Powers, there’s really only one job for you. It was unthinkable that he would do anything else with his life other than hit home runs and make terrible hair decisions.

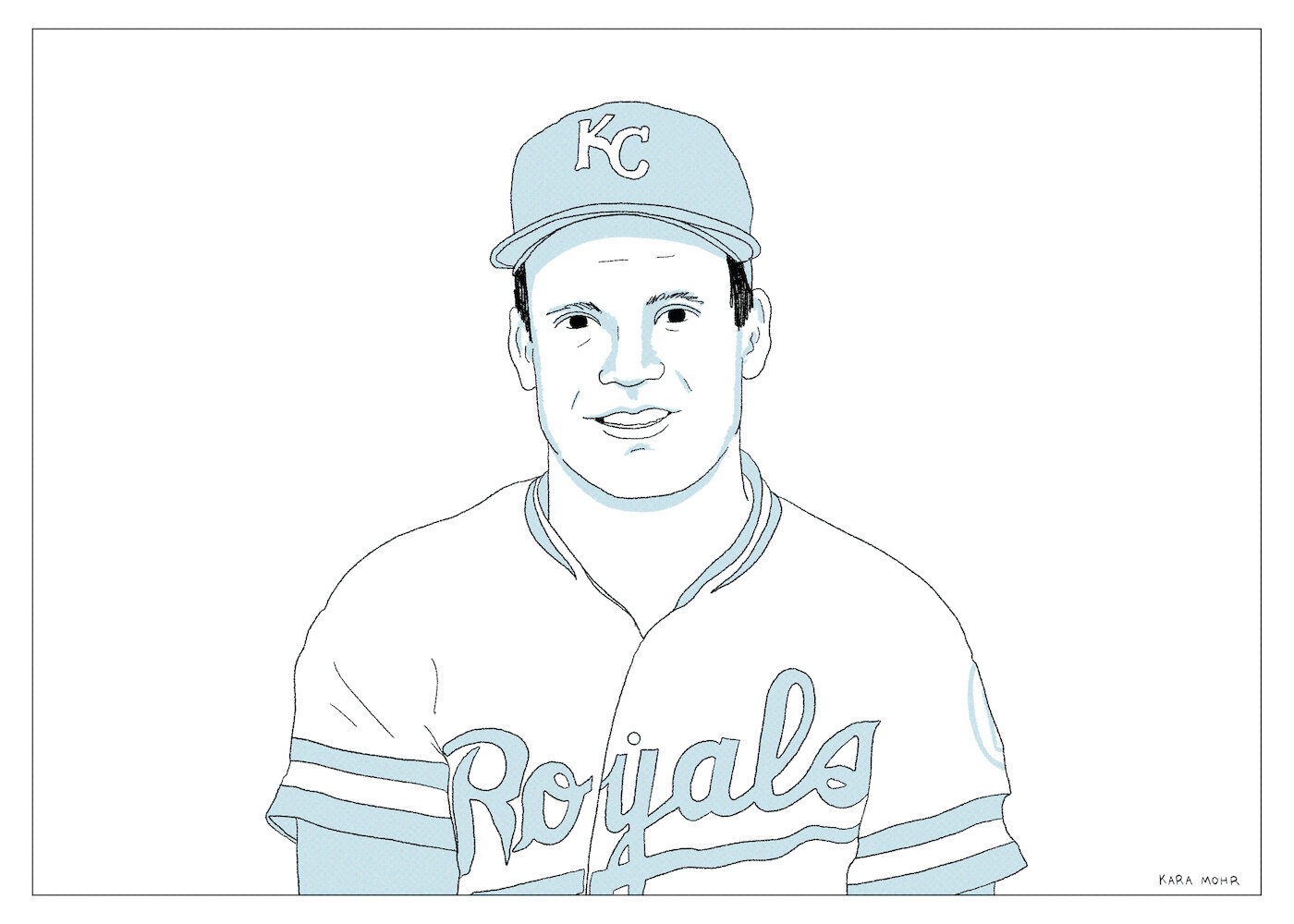

George Brett “The Bellagio Story”

At spring training in 2006, the greatest player in Kansas City Royals history told two minor league journeymen about the time he pooped his pants at the Bellagio, underneath the world’s largest installation of Dale Chihuly blown glass. The story is well known among Youtube diggers, Brett enthusiasts and, perhaps, baseball-inclined gastroenterologists. The mystery of this great story is not what plagues the Hall of Famer’s colon or how it relates to his Pine Tar Homer or whether it is even true, but rather why George Brett was so proudly insistent on the matter of his incontinence.

Eddie Murray “Steady Eddie”

To this day, it still bums me out. It’s been twenty five years, longer than Eddie’s playing career. I’ve had plenty of time to let things go. But not this. I can’t quit it. At least twice a year, I have dreams where he’s still playing. I see him on TV up at the plate, no batting gloves, adjusting his belt, glaring at the pitcher. They called him “Steady Eddie” because he was exactly that. He wasn’t the most prodigious power hitter or the slickest fielder or fastest runner. But for the first half of his career, he was the most complete hitter in the game. But then, in 1997, at the age of forty-one, he was demoted to the minors before finishing out his great career with a whimper. I am certain that he’s moved past the indignity. But, I have not.

Steve Balboni “Bye Bye”

Steve Balboni’s body so exquisitely matches his surname that one would expect a rough Italian translation for Balboni to be “husky designated hitter.” Perhaps there is a village—maybe a small timber community in Northern Italy — where prosperous, mustachioed Balbonis have swung felled trees since time immemorial. Plus, to a seven-year-old in 1985, the name sounded a lot like a combination of Baloney and Bambino — which, frankly, just made sense. As a child, it was unspeakably obvious what “Balboni” signified. Today, as a grown man, it is almost frighteningly unclear.