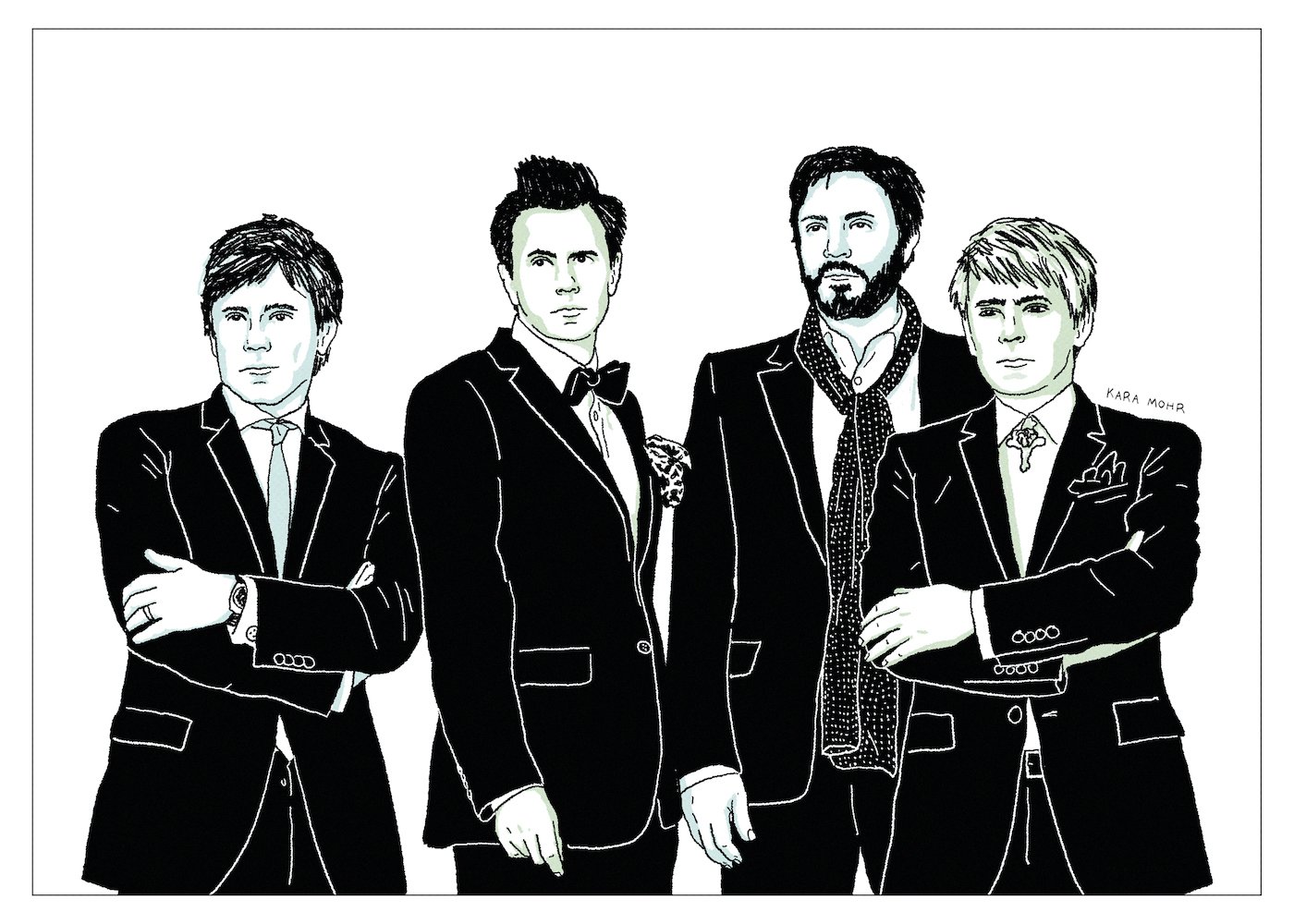

Duran Duran “All You Need Is Now”

By the time Duran Duran tired of their plight as Tiger Beat cover boys, it was too late. They would never be Chic meets Roxy Music, with a dash of The Sex Pistols. The corner of the world that they dreamed of had been claimed by New Order, The Cure and The Smiths. They were doomed to be Pop stars. And they could not tolerate it. After half a decade of fame, fortune, drink, drugs, and screaming girls, they splintered, and then buckled. And they’ve spent roughly the last forty years trying to put things back together — carefully toeing the line between looking back and looking forward. Their efforts included a forgettable covers album, a reunion of The Fab Five and a collaboration with Timbaland. But nothing worked. It increasingly seemed that Duran Duran would be remembered as one of the greatest Pop bands from the greatest moment in the history of Pop — and nothing more. Until, one day, Mark Ronson dared to wonder: “What if that moment returned?” Or rather, “What if we could recreate it? What if, thirty years later, we made the follow-up to “Rio?”

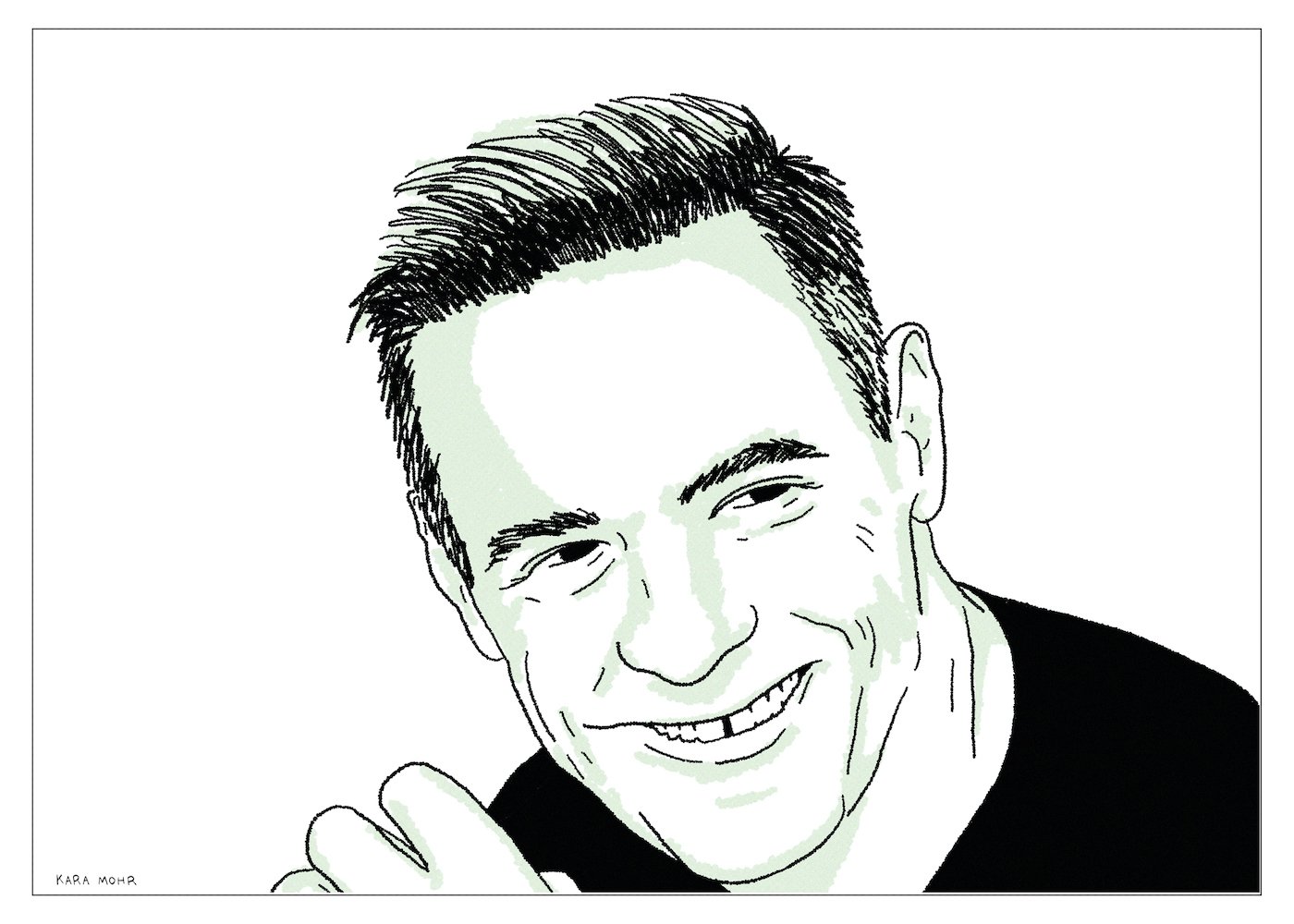

Ric Ocasek “Nexterday”

Ric Ocasek’s life after The Cars included a series of charming, lower stakes solo albums in between gigs as a “record guy.” For most of the 90s, he was a talent scout for Elektra Records and an elite producer for hire. But with Weezer’s “Blue Album,” Ocasek graduated from producer to “super-producer” — which meant he could do whatever he wanted, including making albums for Le Tigre and Brazilian Girls. It also meant that he could write poetry and paint and be the husband of a supermodel. He trimmed the New Wave mullet an inch or two, and maybe he added some lines to his face, but he still hid under the shades and bangs. He still wore oversized tops, buttoned all the way up. And he still had that odd earring dangling. In contrast, by 2005, Blondie was a nostalgia act. David Byrne was more high art than Pop. Sting made listless world music. And Duran Duran survived through the wonders of modern medicine. But Ric Ocasek, it seemed, had won. He’d done what Joey Ramone and Tom Verlaine never could -- stay weird and thrive. All of which makes his final solo album, “Nexterday,” hard to explain.

Imperial Teen “Feel the Sound”

By any reasonable standard, they never should have survived. All of those nineties “Buzz Bin” bands are gone. Fastball. Gone. Harvey Danger. Gone. Semisonic. Technically not gone but also gone. Marcy Playground. Either buried deep or gone. But Imperial Teen — the gender equitable, semi-queer group, who that sounded like ABBA if they’d swallowed The Pixies and who had that guy from Faith No More — kept going. Even after their first can’t miss single somehow missed. Even after they moved away and got other jobs and had kids. Even after their record sales dwindled. Even then, they’d get back together and make near perfect records full of bratty swagger, three part harmonies and hooks for miles. They’re the secretly Pop band who refused to get popular but also the Twee Indie act who never cowered. Which makes them a minor miracle.

Lyle Lovett “Release Me”

Has there ever been someone so completely reliable as Lyle Lovett who looked so completely dodgy as Lyle Lovett? One of his eyebrows is perpetually raised while the other sits still. His mouth turns down in one corner while the other side purses. When he smiles, it looks like he’s in pain. And don’t even get me started with the hair. On the most superficial level, he does not look like a guy you can trust. And yet, by the 1990s, it was settled fact: Lyle Lovett is completely trustworthy. See the piles of four star reviews. The six straight Gold (not Platinum, because that would be too showy) albums. The four Grammy wins. And the fact that, in 2012, when he was making his “contractual obligation album” — the thing that is supposed to be resentful and perfunctory — he was still impossibly mannered and listenable. Turns out that Lyle Lovett is the exact opposite of dodgy.

Clap Your Hands Say Yeah “The Tourist”

Twelve years after Pitchfork landed on his head, Alec Ounsworth was still making music as Clap Your Hands Say Yeah. And while he may not have been the first guy to go straight from the basement to the main stage, he was likely the first one to do so without a record deal. Ounsworth was never exactly famous, but he is famously introverted. And that disposition led him from the brink of stardom to a career of relatively minor albums and concerts inside the living rooms of fans. At forty, married and with a daughter, but still proudly without a record label, Ounsworth reconstituted CYHSY to sing us some songs about middle age ennui. “The Tourist” is almost exactly what its title promises and mostly what long time fans were hoping for. Ten oddly melodic, predictably anxious tunes about an introvert who wants to be seen almost as much as he needs to disappear.

John Fogerty “Revival”

Truth matters. Of course. But on the other hand — and especially in the curious case of John Fogerty — who the hell knows? Was he the Mark Twain of his generation or the Atticus Finch or was he just the guy who connected the musical dots between Ricky Nelson, Little Richard and Neil Young? How did the man who was once our answer to Paul and John just one day just disappear? As spectacular as Fogerty’s early run with Creedence was, everything that followed seemed like an unsorted mess. Seriously, what happened? Was he impossible to deal with. Did his muse dry up? Why was he always in court? Who was the hero and who was the villain? Time resolved some things. Lawsuits were settled. Contracts expired. People died. And, of course, John Fogerty had his beloved, if still perplexing, second act.

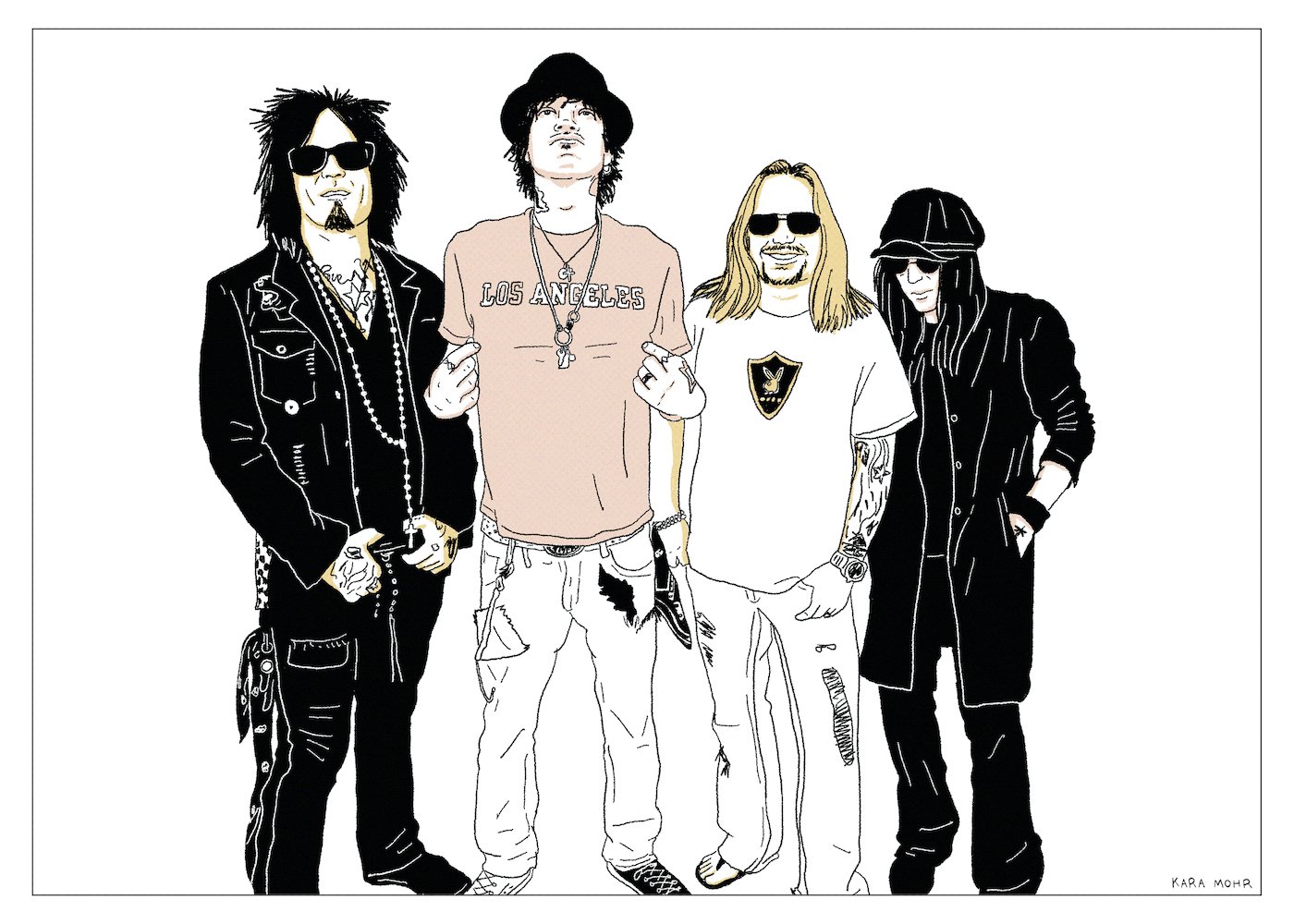

Mötley Crüe “Saints of Los Angeles”

Two bands. Both inspired by The New York Dolls. Both with silly haircuts. Both with bassists who died, though only one of whom stayed that way. Both famous for leaving destruction in their wake. Both accused of nihilism. Both the subjects of gossip, books, movies and films. One was born in 1975 and, for the most part, was done by 1978. The other formed in 1981 and, though they’ve said farewell numerous times, is still going to this day. One of these bands is thought of as high art. Scholarly tomes obsess over them. Meanwhile, the other band -- the generationally popular one -- is the butt of jokes. One is English and enthralls me. The other is Californian and confounds me. The more I considered the two bands, separated by critics and 5,437 miles, the more I had to confront the idea that their Sex Pistols might be our Mötley Crüe.

Weezer “Weezer (White Album)”

Whatever twentieth century Weezer suggested, twenty-first century Weezer signified something else. According to their critics, each successive model of the band represented another victory for irony over vulnerability; a validation of generic Pop Punk and the commodification of Emo. They meant that Blink 182 and Sum 41 and Fallout Boy were the winners. Worse still, it seemed like Rivers Cuomo either embraced it all or just did not care. It was an unmistakable betrayal — like in “Revenge of the Nerds 3: The Next Generation,” when nerd-king Lewis Skolnick grew a ponytail and fraternized with the Alpha Betas. “Everything Will Be Alright in the End” (2014) was Weezer’s promise to be “good” again — a full-throated apology everything that happened after “Pinkerton.” But here’s the thing about promises: they are much easier to make than they are to keep.

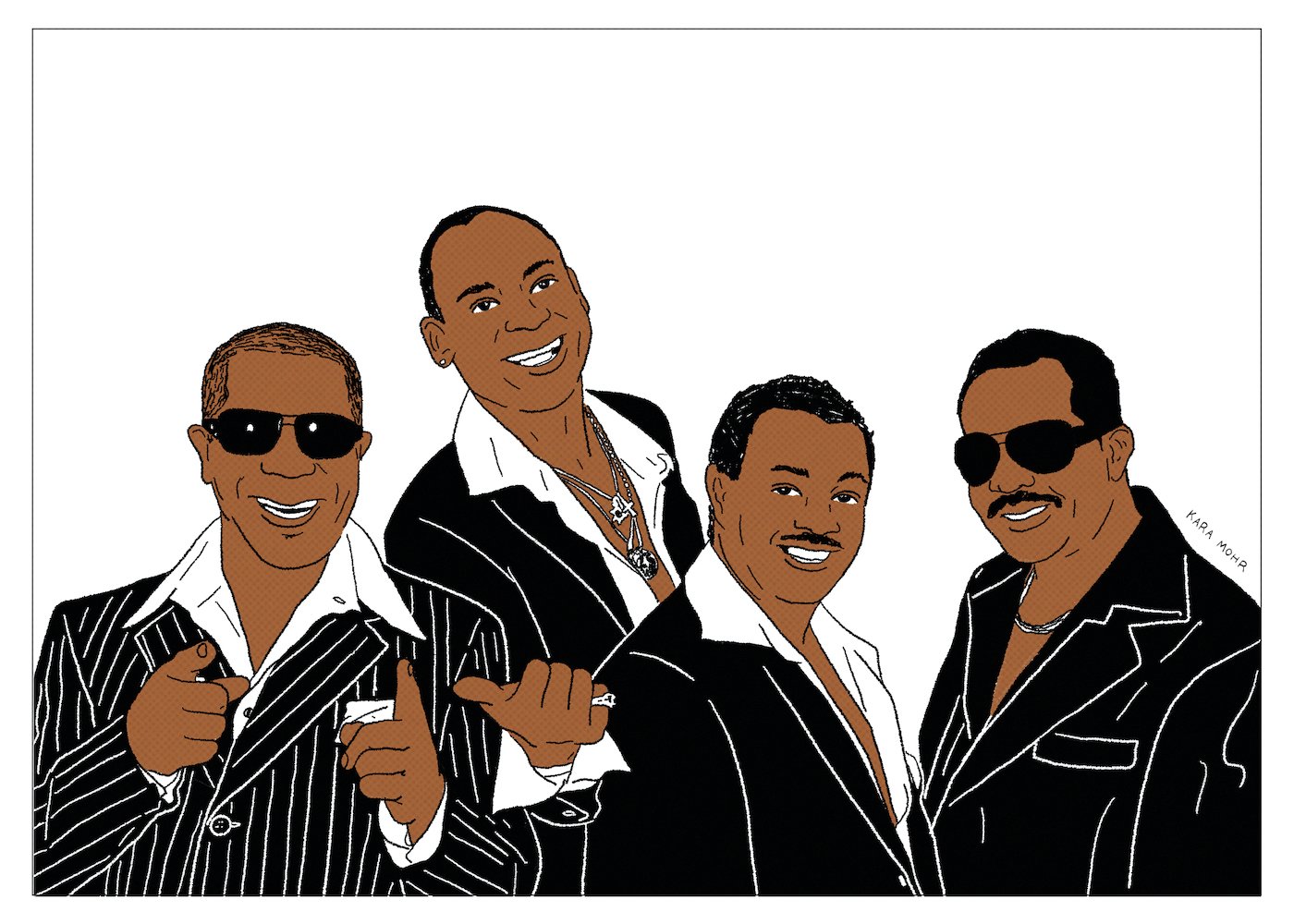

Kool and The Gang “Still Kool”

Many artists straighten out and lighten up as they age. Phil Collins comes to mind. Early Genesis fans could not have imagined “Against All Odds” in the same way that “Sussudio” lovers could not have fathomed “You’ll Be in My Heart.” Similarly, there’s a massive chasm between Cream’s “Tales of Brave Ulysses” and Clapton’s “Change the World.” And yet, compared with Kool & the Gang, those other paths seem almost linear. After nearly twenty years spent dialing down their Jazz and cleaning up their Funk, Kool & the Gang made their way to the top of the charts and into every birthday party, wedding and bar mitzvah the world over. Then, their ensuing hits, from “Joanna” through “Cherish,” got so light that the group began to sound like El DeBarge fronting Chicago. Two decades later, though their classics survived in Hip Hop samples, Kool & the Gang had basically floated away.

Sugar Ray “Music for Cougars”

Years after the clock had counted down from “14:59,” when the endless summer was over and when Mark McGrath went fully blonde, Sugar Ray were on sabbatical. Meanwhile, wunderkind producer, John Abraham, was ascending, cutting records for everyone from Staind to Weezer to Velvet Revolver and Pink. And though in 2008 there was almost nobody on the planet -- including Mark McGrath and his bandmates -- clamoring for a new record from Sugar Ray, Abraham offered the group a deal. Where the rest of us saw a past prime hunk and his band, born from the gunk under Matchbox 20 and Blink 182, Josh Abraham saw unfinished business. So, in 2008, in the face of the zeitgeist, Sugar Ray began recording “Music for Cougars.” Yes — that really is the title.

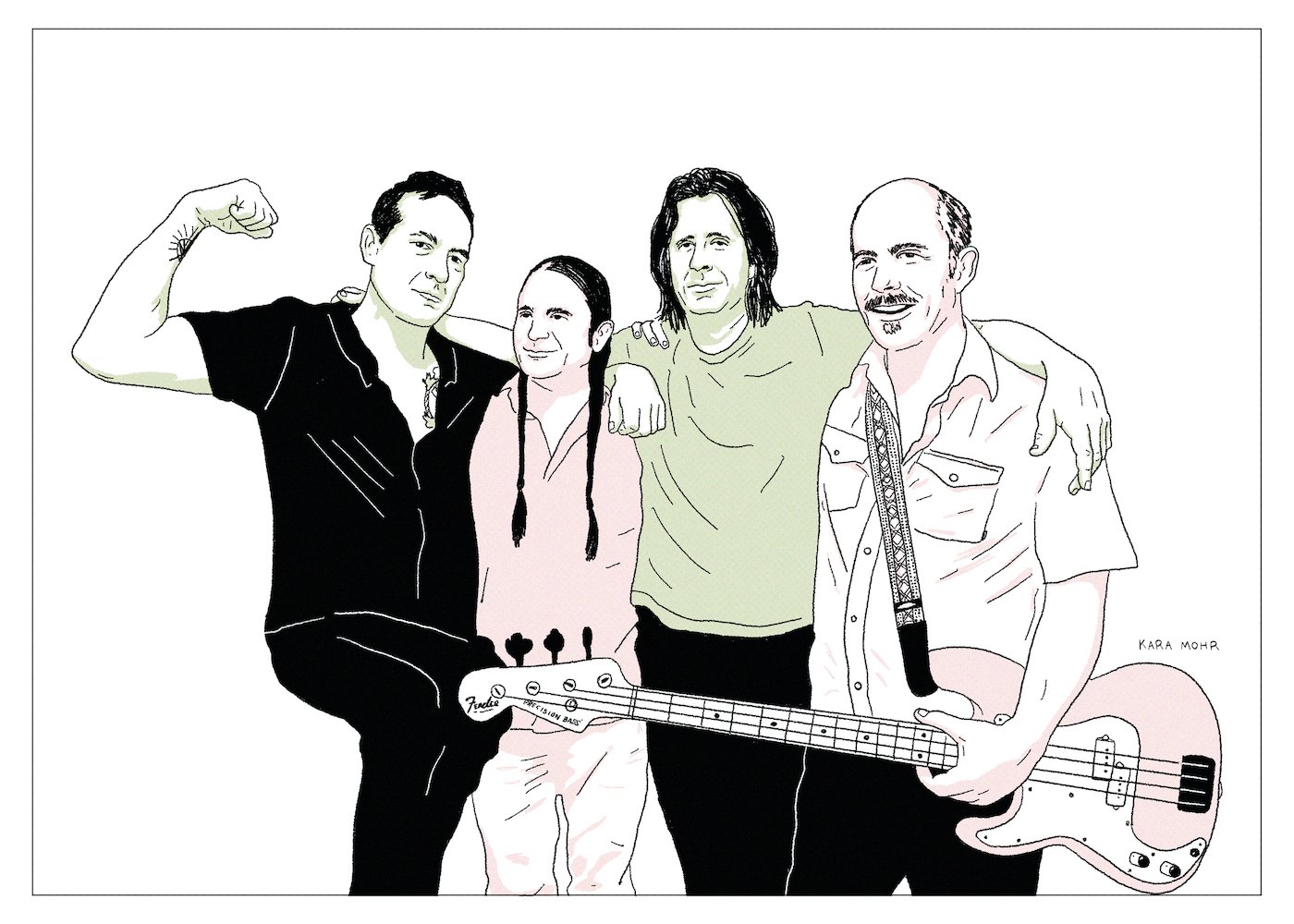

Hot Snakes “Jericho Sirens”

Hot Snakes are a miracle. They are a miracle for how they survived the legends of Drive Like Jehu and Rocket From the Crypt. They are a miracle for how John Reis rolls riffs from a twenty-sided die. They are a miracle for how Rick Froberg screams so loudly, so precisely on tune. They are a miracle for how much force and tension they create and how quickly they release it. They are a miracle for how they disappeared and how, more than a decade later, they came back. But, mostly, they are a miracle for how they marry Rick’s fuck-it-all-ness, with John’s fuck-yeah-ness. That is their greatest miracle.

Ichiro Suzuki “What Else Can I Do”

Like the magical Madrigal children from Disney’s “Encanto,” Ichrio Suzuki was only allowed to be one thing. In his case: the greatest hitter of singles. Just like Madrigals, however, his blessing was also his curse. As a child, when he wanted a day off from the incessant, metronomic process of becoming Ichiro, he just sat down in centerfield and refused to play. His father responded by whizzing baseballs at him. Later, when Nobuyuki Suzuki turned over the training of his son to high school coaches, he had one instruction: “No matter how good Ichiro is, don’t praise him. We have to make him spiritually strong.” In perhaps the most understated reflection on one’s childhood ever, Ichiro recalled, “It bordered on hazing and I suffered a lot.”

Funkadelic “First Ya Gotta Shake the Gate”

When it comes to George Clinton, nothing is simple. Memories are unreliable. Facts are covered in Funk. Dusted with glitter. Stored on old, warped floppy discs, under piles of drugs, in the basement of a barber shop in New Jersey. By 2014, when Clinton turned seventy-thee, the story of Parliament-Funkadelic was something in between a cold case and a myth. Part of me thought that they were the single greatest influence on contemporary Pop music. Another part was convinced that they were the biggest tragedy in the history of Rock and Roll. I thought I’d never know the truth. But then, within a single month, George released his autobiography and Funkadelic released a thirty-three song, three and a half hour, triple album — their first new music since 1981.

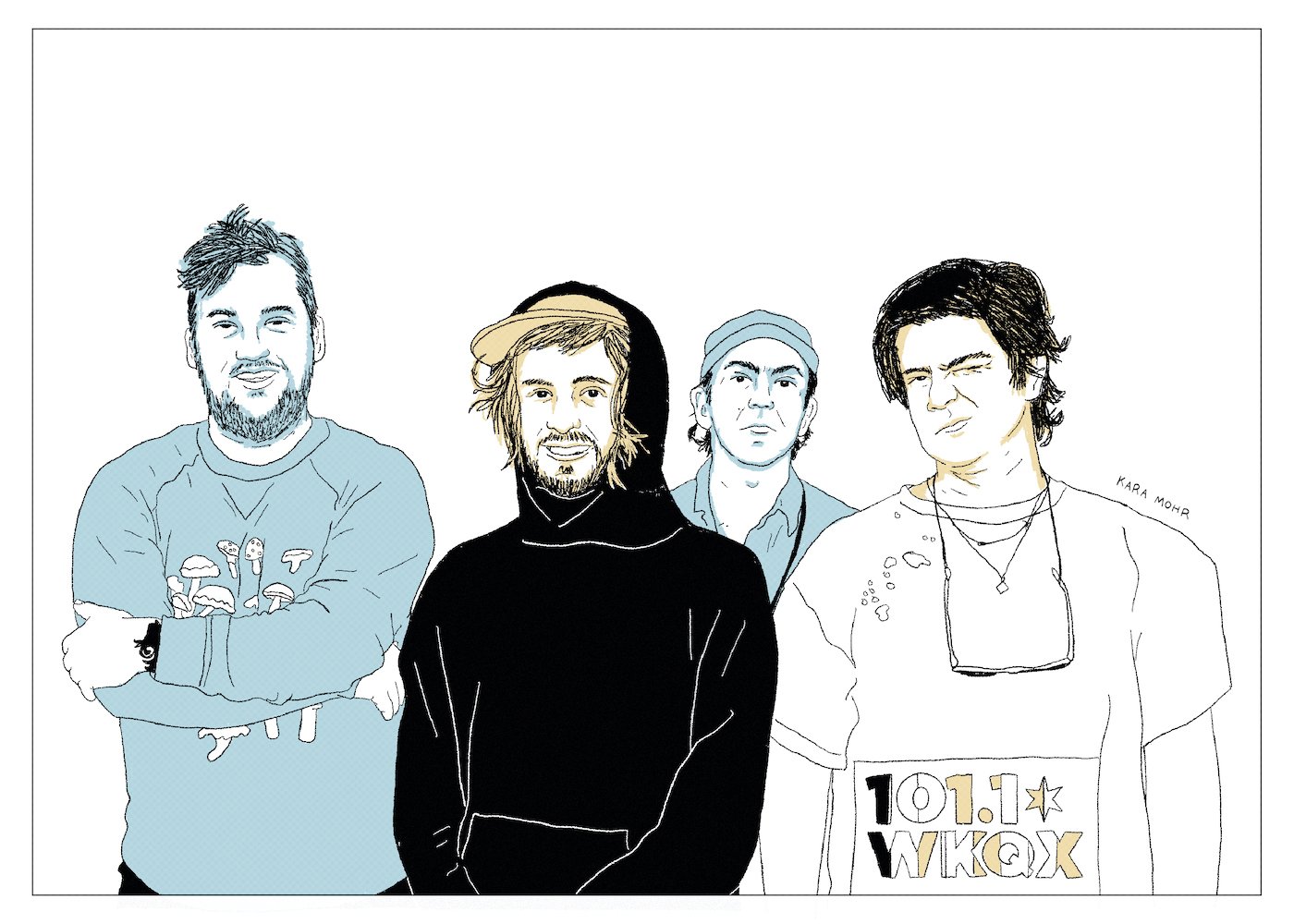

Modest Mouse “Strangers to Ourselves”

Almost two decades into his unlikely career — in between his fifth and sixth albums — Isaac Brock got stuck. It had been many years since “We Were Dead.” Uppers and psychedelics weren’t helping. The line of producers wasn’t helping. The sleeplessness definitely wasn’t helping. He just could not move forward. He was stuck in a loop, like a fatal record scratch. All he could see was the end of everything and how we all knew it was coming and how we all distracted ourselves from it and how we all vacationed and partied and Netflixed, full well knowing that we were fucked. To compound matters, he was being stalked. In fact, he was being stalked by several people. There is little doubt that Isaac was in the throes of paranoia during this time, but — yes — he also really was being stalked. It was that version of Isaac Brock, who, along with seven other band members and four other producers, eventually released “Strangers to Ourselves” in 2015.

Darius Rucker “Learn to Live”

For over a decade, Hootie and the Blowfish were the butt of jokes — a 90s cliche nested between bad Gap sweaters and Sugar Ray. The probability of the backlash, however, was only surpassed by the improbability of Darius Rucker’s reemergence in Nashville in 2008. While his reign as the most successful Black musician in Country music now appears obvious, it was once, briefly, the object of cynical eyebrow raises. Taken together -- the backlash and the genre hop -- Rucker’s career resembles that of the Bee Gees and Ray Charles. He’s not the writer that Barry Gibb was and he’s not a sliver of Ray. But, also, he’s not Shania Twain or Mark McGrath or Rob Thomas. And he’s definitely not Hootie. He’s Darius Rucker, Country Music Star.

Pedro the Lion “Phoenix”

In 2006, after a decade as the mostly Christian, nearly secular, too fast for Slowcore, too slow for Indie Pop darling, David Bazan hung up Pedro the Lion. He was at a crossroads — in life, faith and music — and had to decide. The path Bazan chose was likely the harder one. He dried himself out, and returned as a solo artist, playing tiny, living room shows to anyone who wanted him. It was a living, but it was also lonely as hell. Years seeing his kids grow up over FaceTime. Nights in cheap hotels. Days on the highway, watching mile markers pass glacially while his his life flew by at twice the rate. When he finally ran out of gas, he did the logical thing: he reconvened Pedro the Lion and returned to Phoenix, Arizona, the place he was born and where he was taught to believe.

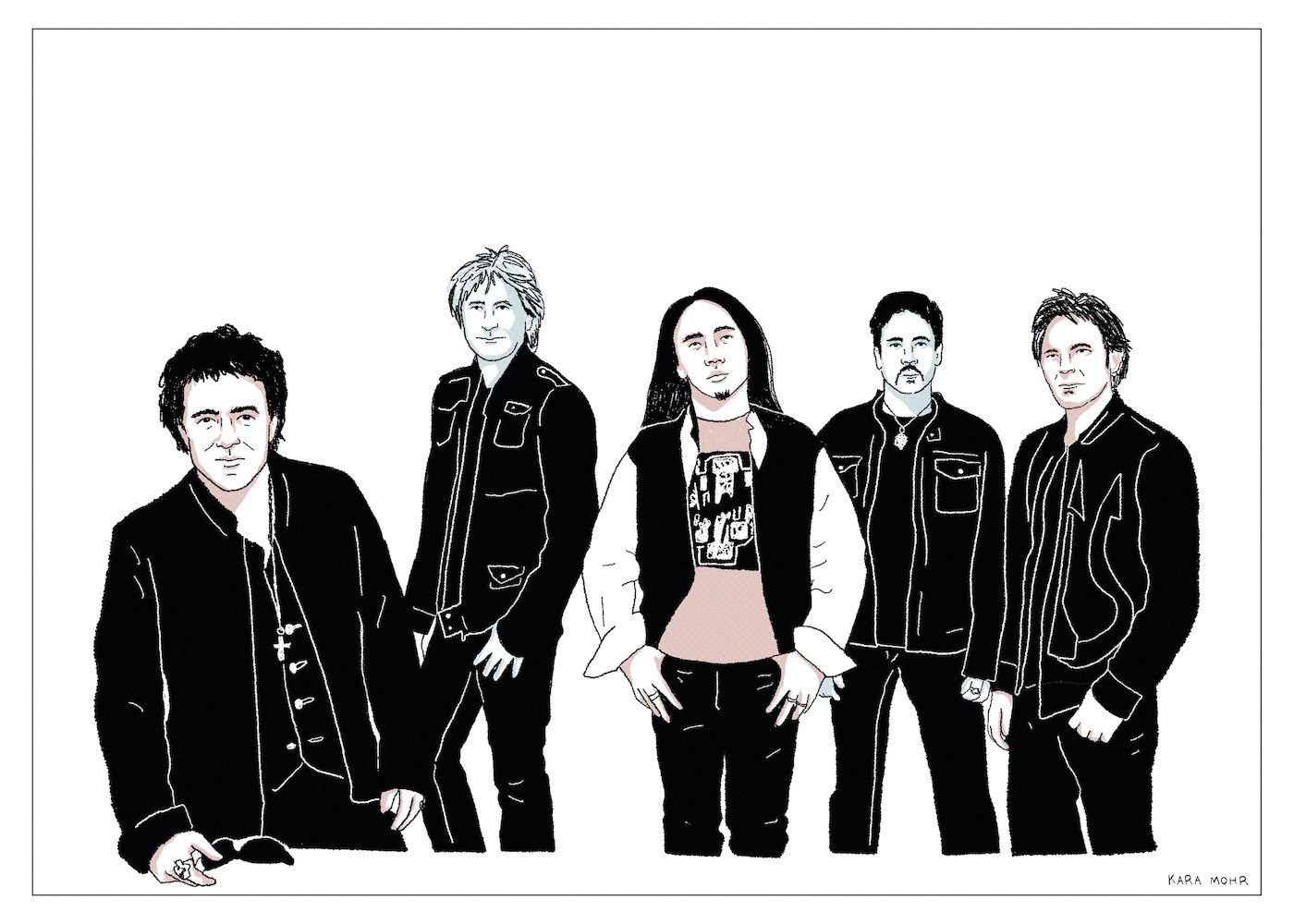

Journey “Revelation”

By 2006, Journey were on the ropes. The former heavyweight champs of Arena Rock had exhausted every possible alternative. Version 3.0 with Steve Perry broke down. Version 4.0 with Steve Augeri fizzled. Neal Schon didn’t need the money. And he probably didn’t need Journey, either. But we did. Those of us who grew up at skating rinks and on Atari — we could not stop believing. So, just like he’d done before, Schon found the best thing. On Youtube, he spotted a feathery haired, Steve Perry soundalike with a fairy tale backstory. And, just like that, Journey 5.0 released an affordably priced, three disc set through Walmart. One album of new material and two more of extraordinary karaoke. It was exactly what middle-aged, middle America needed.

Bryan Adams “Shine a Light”

Almost forty years after he burst onto our radios, with a voice that humbled Rod Stewart and a style that translated Johnny Cougar into Canadian, Bryan Adams was still going strong. Arenas full of fans were shouting along to “Summer of 69” and crying along to “(All I Ever Do) I Do it For You.” He was closing in on sixty. He’d already sold a hundred million albums and topped every chart in the world. But, he still sounded exactly like himself, which is to say both like nobody else and like a hundred other guys. Naturally he looked older — more refined. His hair was richly coiffed and he’d swapped his leather jacket for a designer blazer. He’d even built a second career as a photographer — his pictures hung on gallery walls. There were only two things left for him to do: make new music with Ed Sheeran and prove to the world that “uncomplicated” is the opposite of an insult.

Duncan Sheik “Legerdemain”

In the mid-90s, after the crater of Alt Rock, a softer, lighter second wave followed, delivering Bubble-Grunge to Middle America. Though nominally inspired by their predecessors, Goo Goo Dolls and Matchbox 20 steered closer to the middle of the road than to its edges. It was during this flaccid period that Duncan Sheik appeared on the scene — similarly strummy, but better educated and mopier. His fans were certain that a nascent Nick Drake (or at least a Grammy) lurked inside Sheik. However, booze and pity partying ensured otherwise. That was, until 2006, when he wrote the music for “Spring Awakening,” an unexpected Broadway hit. It was not “Pink Moon,” but it was a narrative change. Nearly ten tears later, in middle-age, Duncan Sheik checked into rehab, got himself a blog and — against all odds — made the excellent record his college buddies had always hoped for.

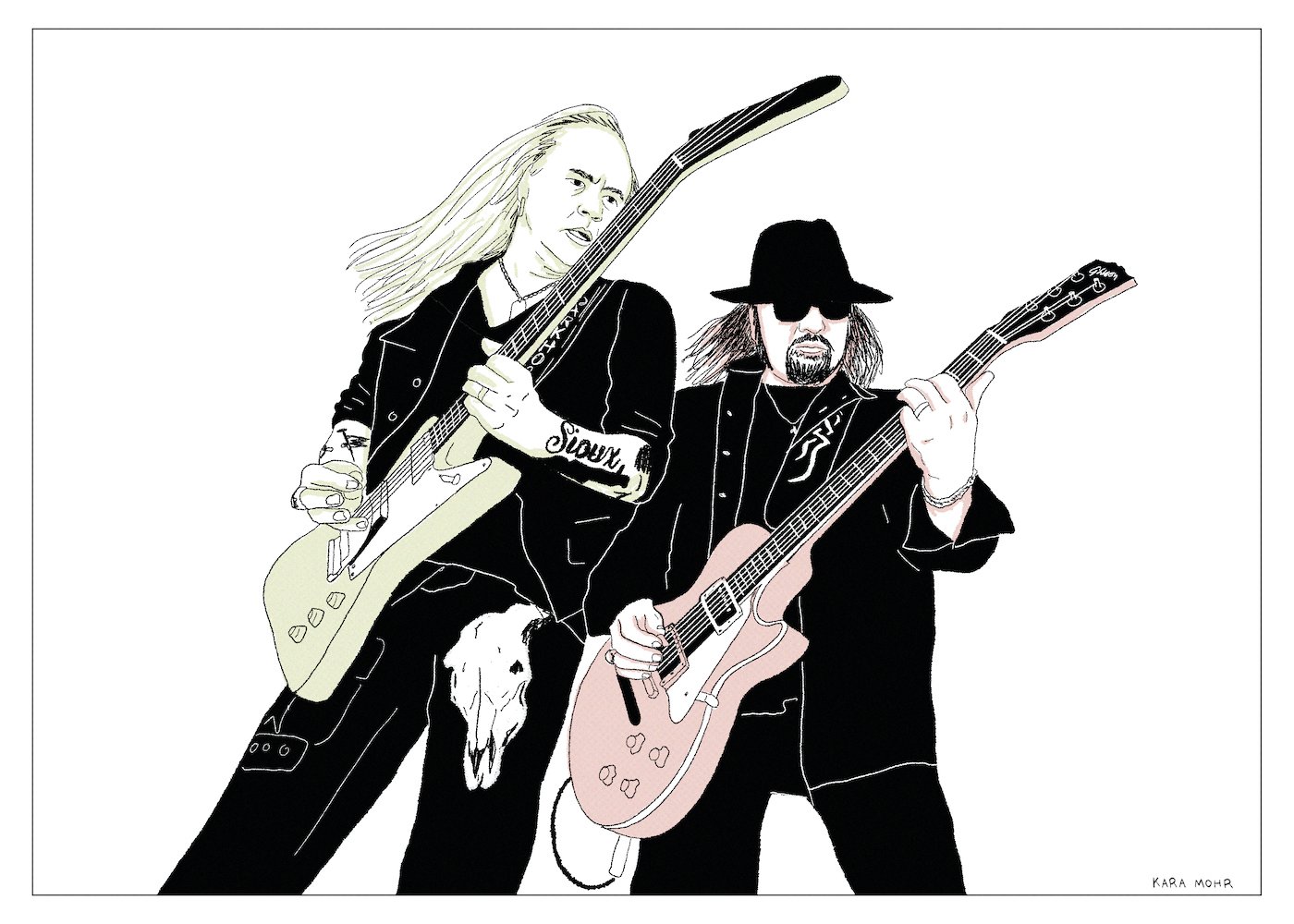

Lynyrd Skynyrd “God and Guns”

Some things in life are hard to talk about openly. For example, sex and money. When guys talk about sex or money, we tend to resort to cliches or jokes or hyperbole. On the other hand, it’s much easier for us to talk about music. In fact, we love to talk about music. Who are your bands? Are you a Stones guy? A Phish guy? A Blur guy? A Smiths guy? It’s organizing and safe. It’s the way we talk about our feelings, without really talking about our feelings. And it generally works for us. Except, of course, when it comes to Lynyrd Skynyrd. And especially when it comes to their 2009 album, “God & Guns,” which — to complicate matters — is absolutely not terrible. It may even be good — even when it’s being awful.