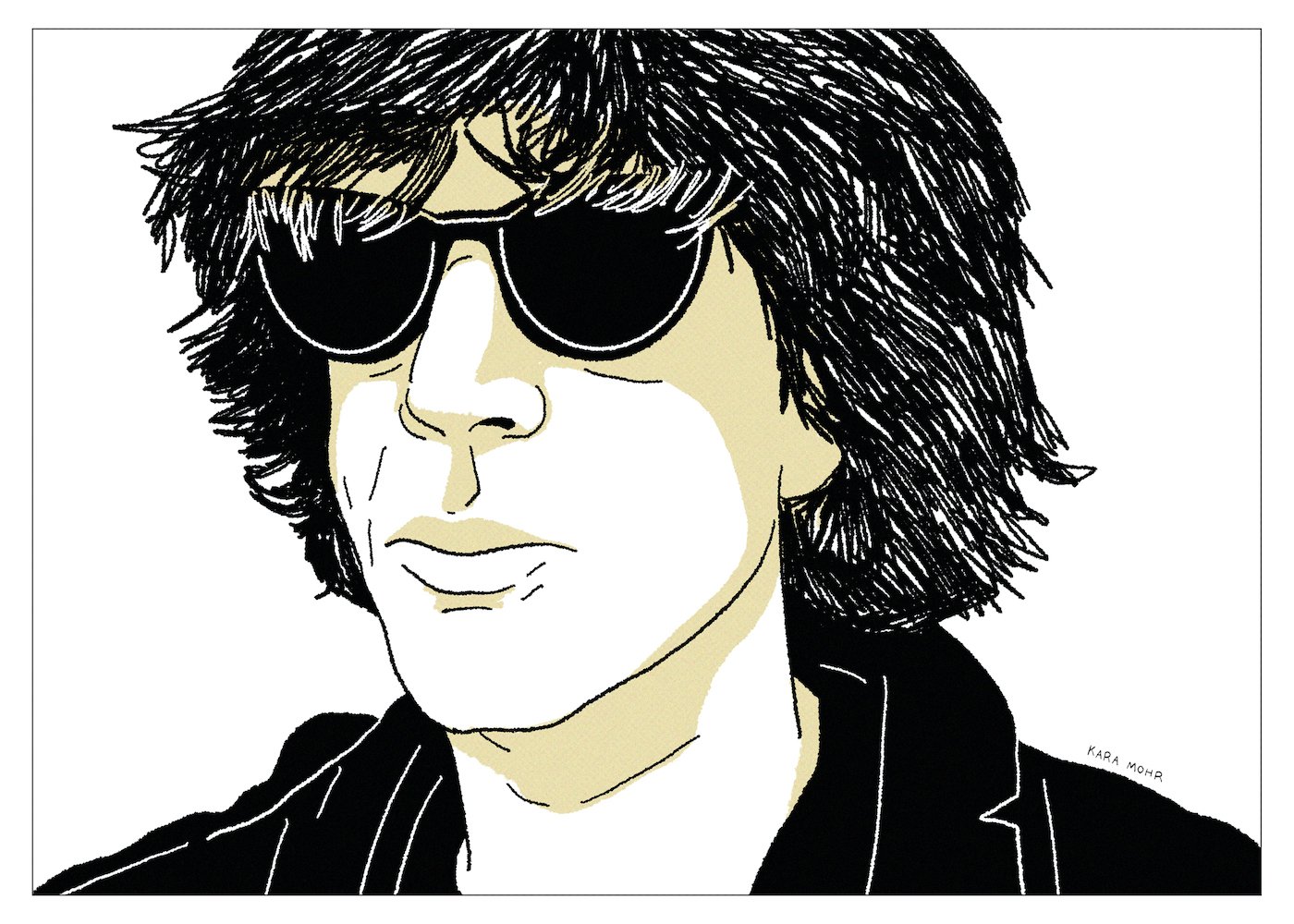

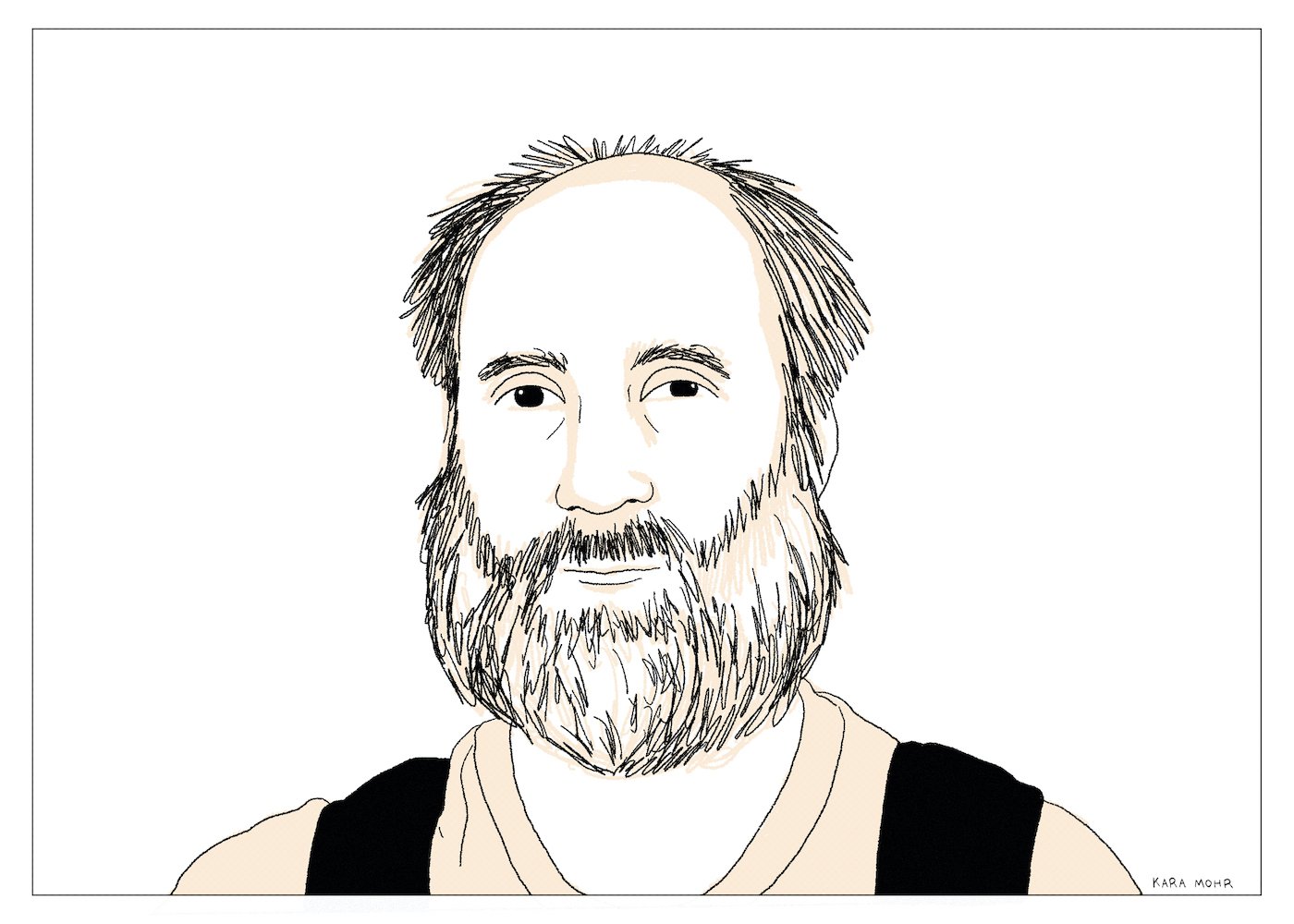

Ted Leo “The Hanged Man”

From 2000 through 2010, Ted Leo was the mainest of Indie Rock mainstays. He and his band released a string of reliably thrilling albums, distinguished by his breathless tenor and progressive politics. Ted Leo and The Pharmacists were so excellent, in fact, that it seemed a foregone conclusion he would one day break through. That Ted Leo would eventually be an important, prestige act felt inevitable. After all, they had their Billy Bragg and their Elvis Costello, so we could have our Ted Leo. He was simply too good — too musical, too smart and too hard working — to imagine any alternative. The sparkling reviews continued along with the steady uptick in sales, until he reached the height of sub-popularity. And then, just when we assumed something monumental was about to happen for Ted Leo, it did. But it was not at all what anyone expected.

Dim Stars “Dim Stars”

Though it was released in 1991, “Dim Stars” sounds like New York City in 1988 — when Jon Spencer was fronting Pussy Galore and before Sonic Youth got a major label deal and when Avenue A was still sketchy and when everything stunk of imminent recession. Like all of those other things, you could call “Dim Stars” loose and offhanded, or you could call it sloppy. You could call it artful or avant garde, or you could say that it sounds like shit. But in fact, it really sounds like four different things. One, like Sonic Youth with Richard Hell splitting the difference between Thurston and Kim. Two, like a poorly made sequel to “Destiny Street.” Three, like an overqualified Scuzz Rock band that had not yet found its groove. And, finally, like a post-structuralist hipster cover band.

Chain and The Gang “In Cool Blood”

Like Nation of Ulysses before them, The Make-Up were more legendary than popular. And so, just five years after they first appeared, the most stylish, most ideological band on the planet was dissolved. In the Aughts, Ian Svenonius (along with Michelle Mae and Neil Hagerty) formed Weird War, but because socialism might be bad for business, the singer spent most of that Aughts moonlighting as a subject slash contributor for Index Magazine — and anyone else who wanted his ideas and his hair for their pages. By 2009, he was more an essayist, a great interview, a great photoshoot, and a hipster cad than he was a rock and roller. He was to Vice what Fran Lebowitz was to Vanity Fair. Until one day — when he’d either run out of ideas or when he had too many out of them — Svenonius started another new band. Chain and the Gang started as a lower stakes, rotating cast of friends and acolytes, sponsored by Calvin Johnson. By then, fans (and critics) were familiar with Svenonius’ Post-Structuralist, Marxist provocateur shtick. What they were less familiar with was his winking, hip-shaking good times.

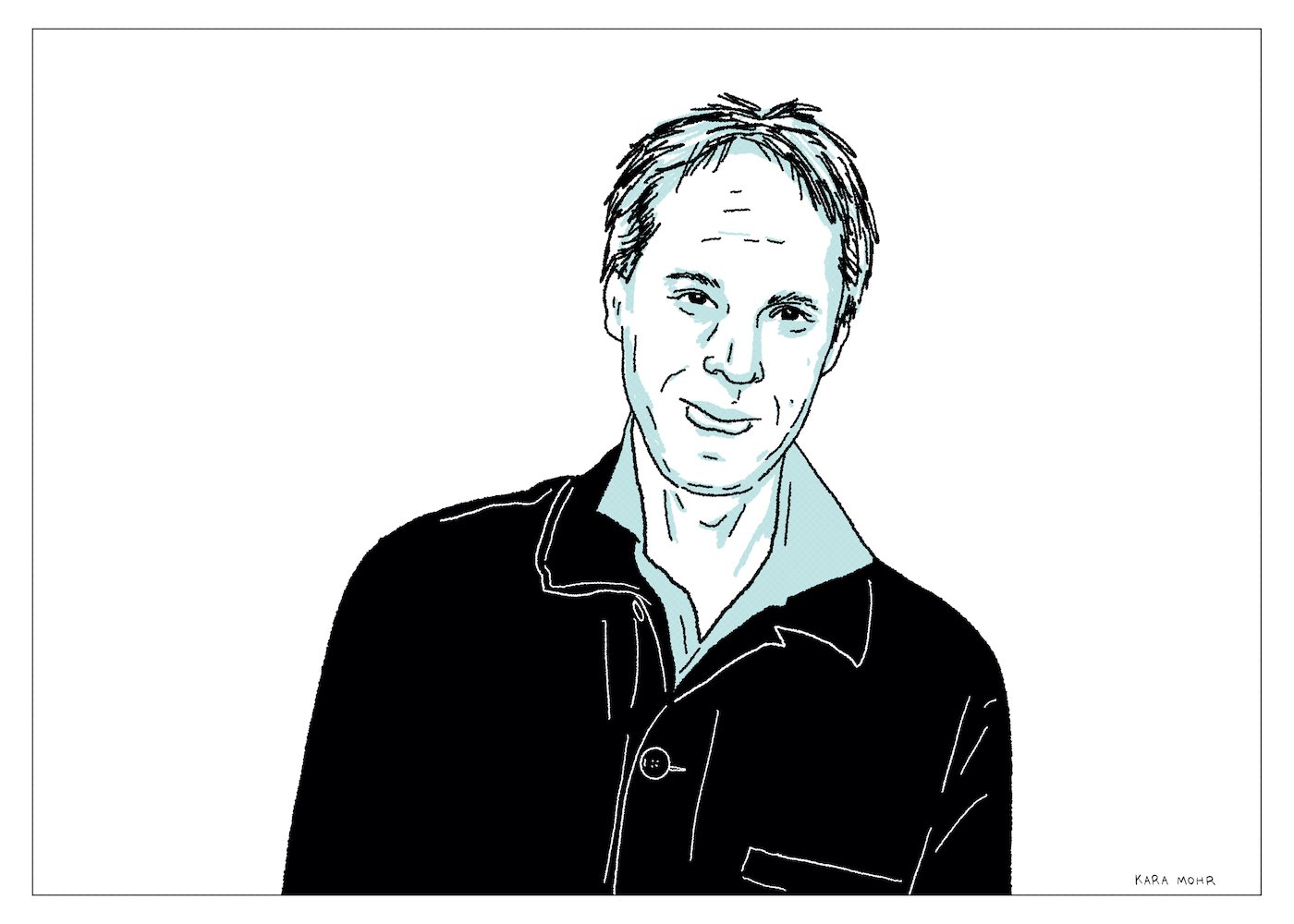

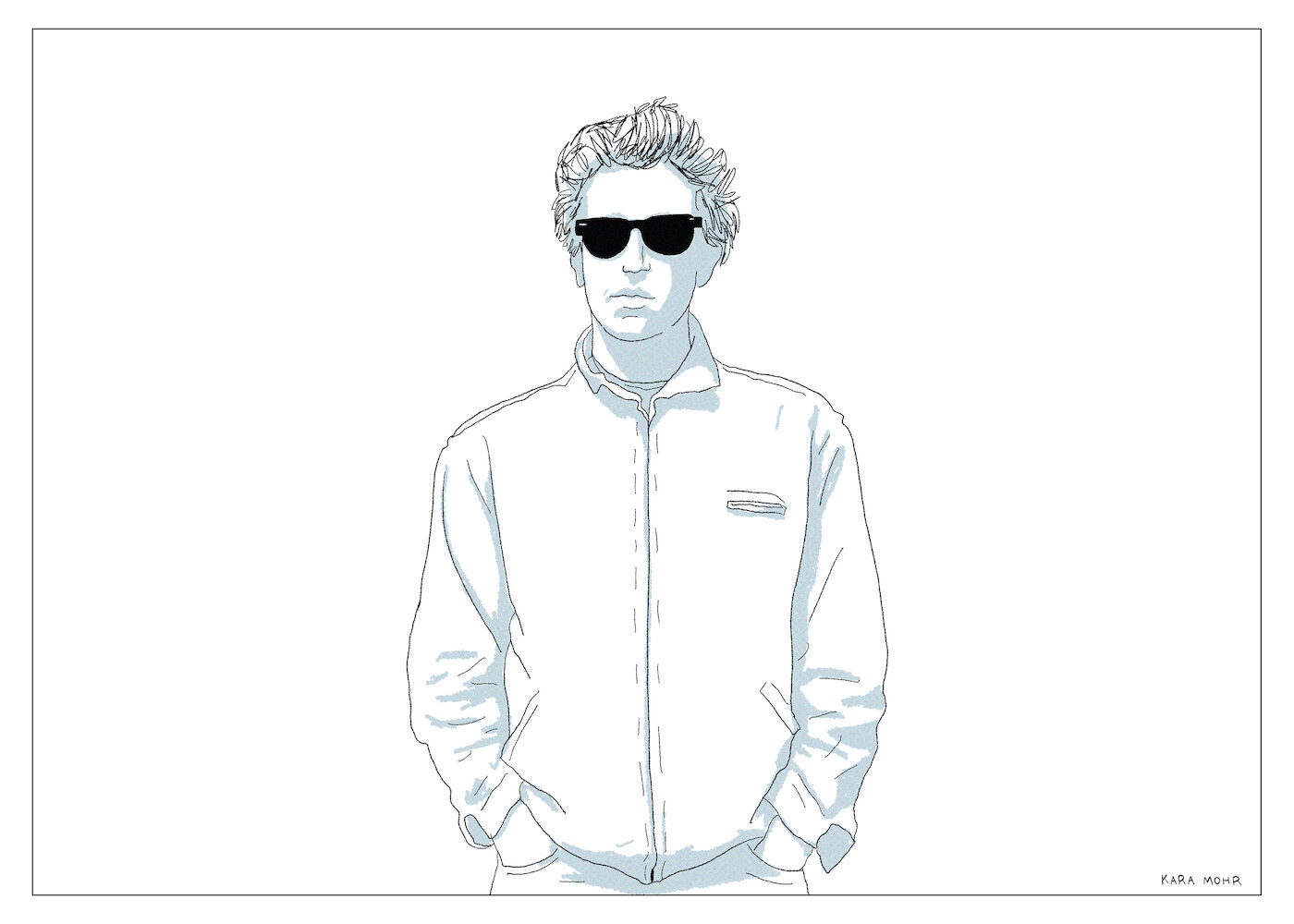

Tom Verlaine (1949-2023)

Of all of the many wonderful things said about Tom Verlaine this past week, the most moving words came, unsurprisingly, from Patti Smith. Her eulogy for The New Yorker, entitled “He Was Tom Verlaine,” was typically elegiac, like a series of black and white photographs narrated with poetic beats and prosaic secrets. Amid the generous obituaries and Twitter tributes — written mostly by strangers — Patti’s essay was so unusually revealing, not because she was betraying any confidences, but rather, because prior to this week, and despite the fact that I spent decades enamored of him, I knew so little about Tom Verlaine. He was not a recluse like Jeff Mangum or an outsider like Syd Barrett or Roky Erickson. But it seemed that, ever since “Marquee Moon” changed everything — and nothing at all — Verlaine was slowly, silently walking in the opposite direction from everything that fans (like me) most wanted from him. His entire career — seemingly confirmed by Patti Smith herself — is a reminder that love is so much more about what we don’t know than what we know for sure.

Fred Schneider “Just Fred”

Fred Schneider was an unlikely frontman. For one thing, he either could not or would not sing. Similarly, he seemed more interested in John Waters than in John Lydon. Fred never dreamed of making the next “Like a Rolling Stone.” He wanted to make the next “Monster Mash.” And so he spent over a decade, from “Rock Lobster” through “Love Shack,” blurring the lines between novelty Pop and artsy Rock. But, in 1996, at the very height of Alt, Fred Schneider reemerged as a solo act. During a time wherein “Alternative culture” had become overly serious, it was revealed that “Just Fred” was produced by Steve Albini and featured a cast of stalwart Indie Rock veterans as the backing band. On the surface, it sounded all wrong. No keyboards. No Kate Pierson or Cindy Wilson. No party. It seemed contrarian and willfully provocative, like hearing that sweet, adorable Alyssa Milano — Sam from “Who’s The Boss” — was making a turn into adult, erotic thrillers. But, in the same way that I definitely checked out “Poison Ivy 2,” I was not not curious about “Just Fred.”

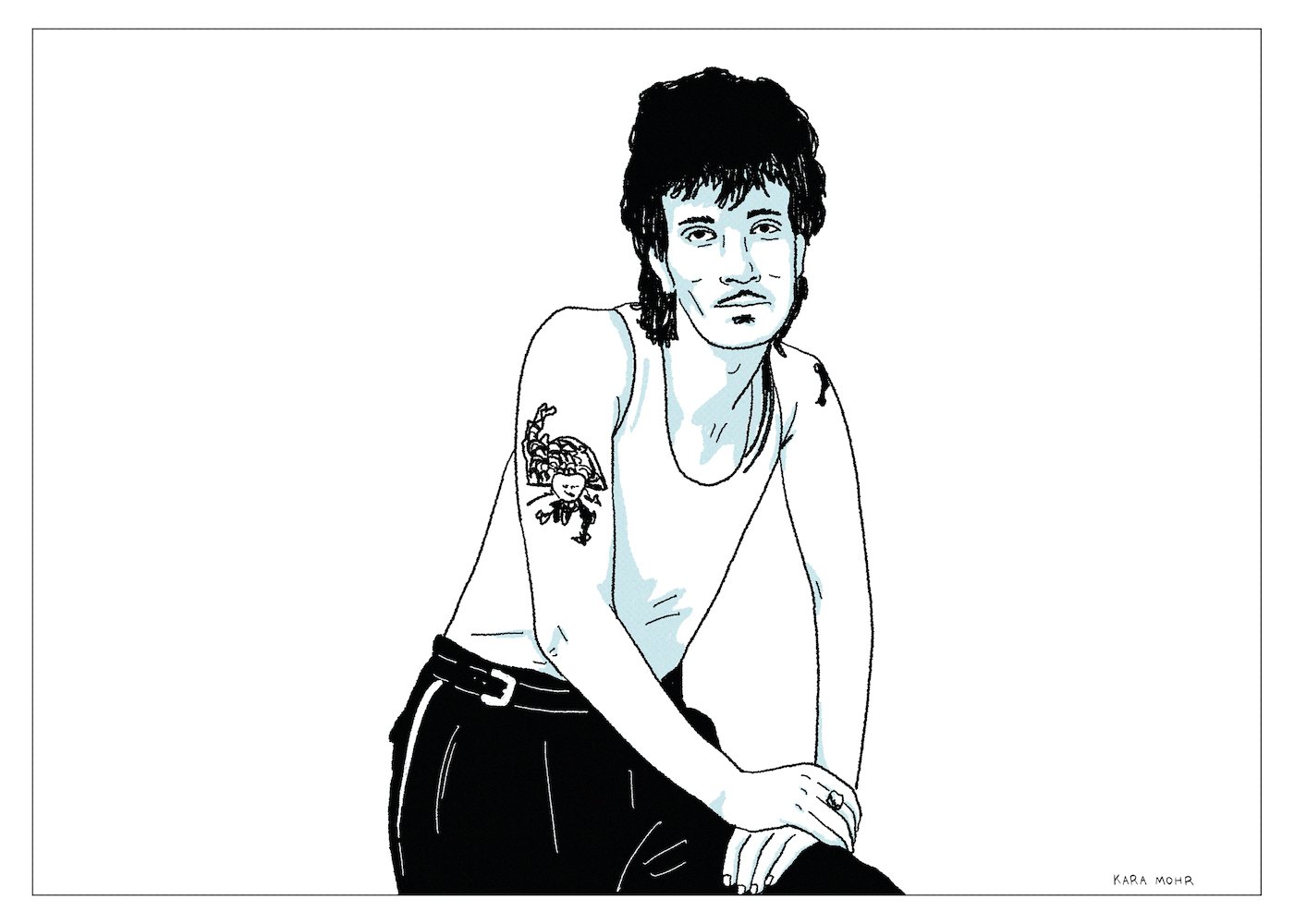

Willy DeVille “Backstreets of Desire”

When Dylan went from folkie hobo to poet in black turtleneck and shades, it seemed like affect. When Bowie went from Ziggy to Thin White Duke, it felt like an art project. And when Madonna went from Material Girl to S&M Barbarella, it came off like a marketing stunt. But Willy DeVille was the genuine article — a real life shapeshifter. The man born William Borsay Jr., from Stamford, Connecticut, would become a Spanish Harlem pimp, a Bowery gutter prince, a riverboat gambler, and a Navajo mystic. In 1992, somewhere between the Bayou and his eventual return to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, he briefly wound up in Los Angeles. And, in spite of crippling addiction and decades of commercial disappointments, Willy made one of the great, barely heard Roots Rock albums of the decade. “Backstreets of Desire” might read like something from Springsteen’s swamps of Jersey, but it sounds like the Los Angeles that made Los Lobos, Tom Waits and Warren Zevon.

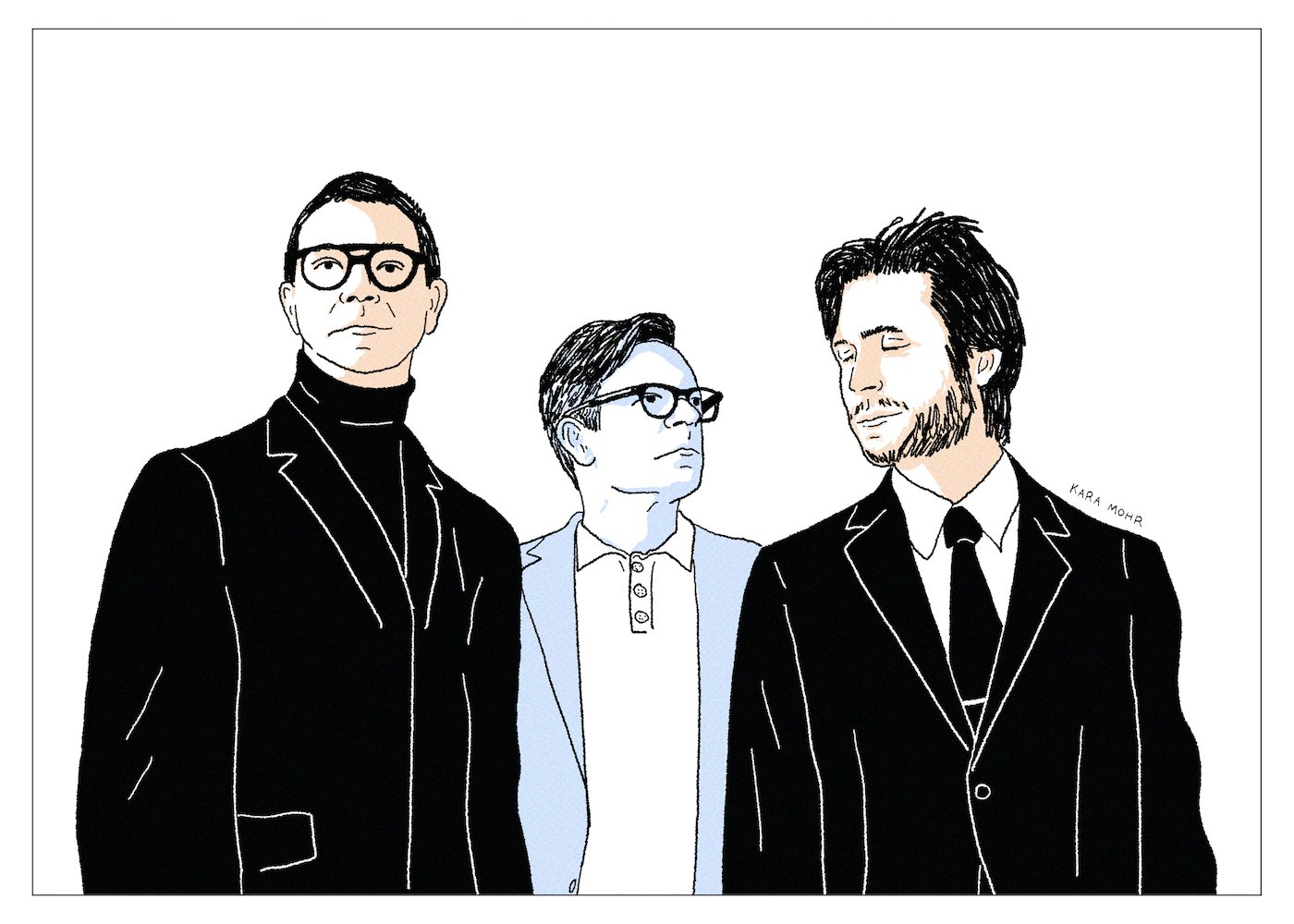

Interpol “The Other Side of Make-Believe”

Whereas most of those Williamsburg by way of Lower East Side bands of the early Aughts balanced post-collegiate pretense with drunken dude-ness, Interpol appeared to be all pretense. The suits. The black on black. The Factory Records of it all. Even before I heard a single note of their music, I was confused as to whether they were satire, or postmodern commentary, or totally earnest, or something I’d never encountered before. Eventually, though, I figured out that the Carlos and the Daniel and the Paul and the Sam I’d seen about town were identical to the ones who were on stage at Mercury Lounge. These were not actors. Those were not costumes. They were maybe not even uniforms. They were skins. And yet, back in 2002, every fiber in me was expecting the truth to eventually be revealed. The other black leather boot had to drop some day. No matter how great their debut album was. No matter how great their follow-up was. No matter how enduring the act, I was convinced that they’d trip up and be revealed as something fraudulent. Twenty years after “Turn on the Bright Lights,” though, I stopped waiting for the backlash.

Imperial Teen “Feel the Sound”

By any reasonable standard, they never should have survived. All of those nineties “Buzz Bin” bands are gone. Fastball. Gone. Harvey Danger. Gone. Semisonic. Technically not gone but also gone. Marcy Playground. Either buried deep or gone. But Imperial Teen — the gender equitable, semi-queer group, who that sounded like ABBA if they’d swallowed The Pixies and who had that guy from Faith No More — kept going. Even after their first can’t miss single somehow missed. Even after they moved away and got other jobs and had kids. Even after their record sales dwindled. Even then, they’d get back together and make near perfect records full of bratty swagger, three part harmonies and hooks for miles. They’re the secretly Pop band who refused to get popular but also the Twee Indie act who never cowered. Which makes them a minor miracle.

Clap Your Hands Say Yeah “The Tourist”

Twelve years after Pitchfork landed on his head, Alec Ounsworth was still making music as Clap Your Hands Say Yeah. And while he may not have been the first guy to go straight from the basement to the main stage, he was likely the first one to do so without a record deal. Ounsworth was never exactly famous, but he is famously introverted. And that disposition led him from the brink of stardom to a career of relatively minor albums and concerts inside the living rooms of fans. At forty, married and with a daughter, but still proudly without a record label, Ounsworth reconstituted CYHSY to sing us some songs about middle age ennui. “The Tourist” is almost exactly what its title promises and mostly what long time fans were hoping for. Ten oddly melodic, predictably anxious tunes about an introvert who wants to be seen almost as much as he needs to disappear.

Hot Snakes “Jericho Sirens”

Hot Snakes are a miracle. They are a miracle for how they survived the legends of Drive Like Jehu and Rocket From the Crypt. They are a miracle for how John Reis rolls riffs from a twenty-sided die. They are a miracle for how Rick Froberg screams so loudly, so precisely on tune. They are a miracle for how much force and tension they create and how quickly they release it. They are a miracle for how they disappeared and how, more than a decade later, they came back. But, mostly, they are a miracle for how they marry Rick’s fuck-it-all-ness, with John’s fuck-yeah-ness. That is their greatest miracle.

Modest Mouse “Strangers to Ourselves”

Almost two decades into his unlikely career — in between his fifth and sixth albums — Isaac Brock got stuck. It had been many years since “We Were Dead.” Uppers and psychedelics weren’t helping. The line of producers wasn’t helping. The sleeplessness definitely wasn’t helping. He just could not move forward. He was stuck in a loop, like a fatal record scratch. All he could see was the end of everything and how we all knew it was coming and how we all distracted ourselves from it and how we all vacationed and partied and Netflixed, full well knowing that we were fucked. To compound matters, he was being stalked. In fact, he was being stalked by several people. There is little doubt that Isaac was in the throes of paranoia during this time, but — yes — he also really was being stalked. It was that version of Isaac Brock, who, along with seven other band members and four other producers, eventually released “Strangers to Ourselves” in 2015.

Pedro the Lion “Phoenix”

In 2006, after a decade as the mostly Christian, nearly secular, too fast for Slowcore, too slow for Indie Pop darling, David Bazan hung up Pedro the Lion. He was at a crossroads — in life, faith and music — and had to decide. The path Bazan chose was likely the harder one. He dried himself out, and returned as a solo artist, playing tiny, living room shows to anyone who wanted him. It was a living, but it was also lonely as hell. Years seeing his kids grow up over FaceTime. Nights in cheap hotels. Days on the highway, watching mile markers pass glacially while his his life flew by at twice the rate. When he finally ran out of gas, he did the logical thing: he reconvened Pedro the Lion and returned to Phoenix, Arizona, the place he was born and where he was taught to believe.

Built to Spill “Untethered Moon”

If I had to design an Indie Rocker -- for a movie character or a book proposal, or whatever -- I’d start with a guy from the Midwest or the Pacific Northwest. He’d be above average height and lanky, but in no way muscular. Maybe he played some baseball in high school, but sports weren’t that important to him. He drinks beer and smokes weed but doesn’t think much about either. He’s introverted, but also has plenty of friends. He’s dreamy -- not in the Jake from “Sixteen Candles” way, but in the always kind of thinking of something else way. He can figure things out. He built his own computer. He can hang drywall. He apparently has a band that nobody has ever heard but that you assume is pretty good. And, though he’s only twenty-something years old, he looks like he could be forty. He’s even got the beard to prove it. That’s the guy — the archetype. His name is Doug Martsch.

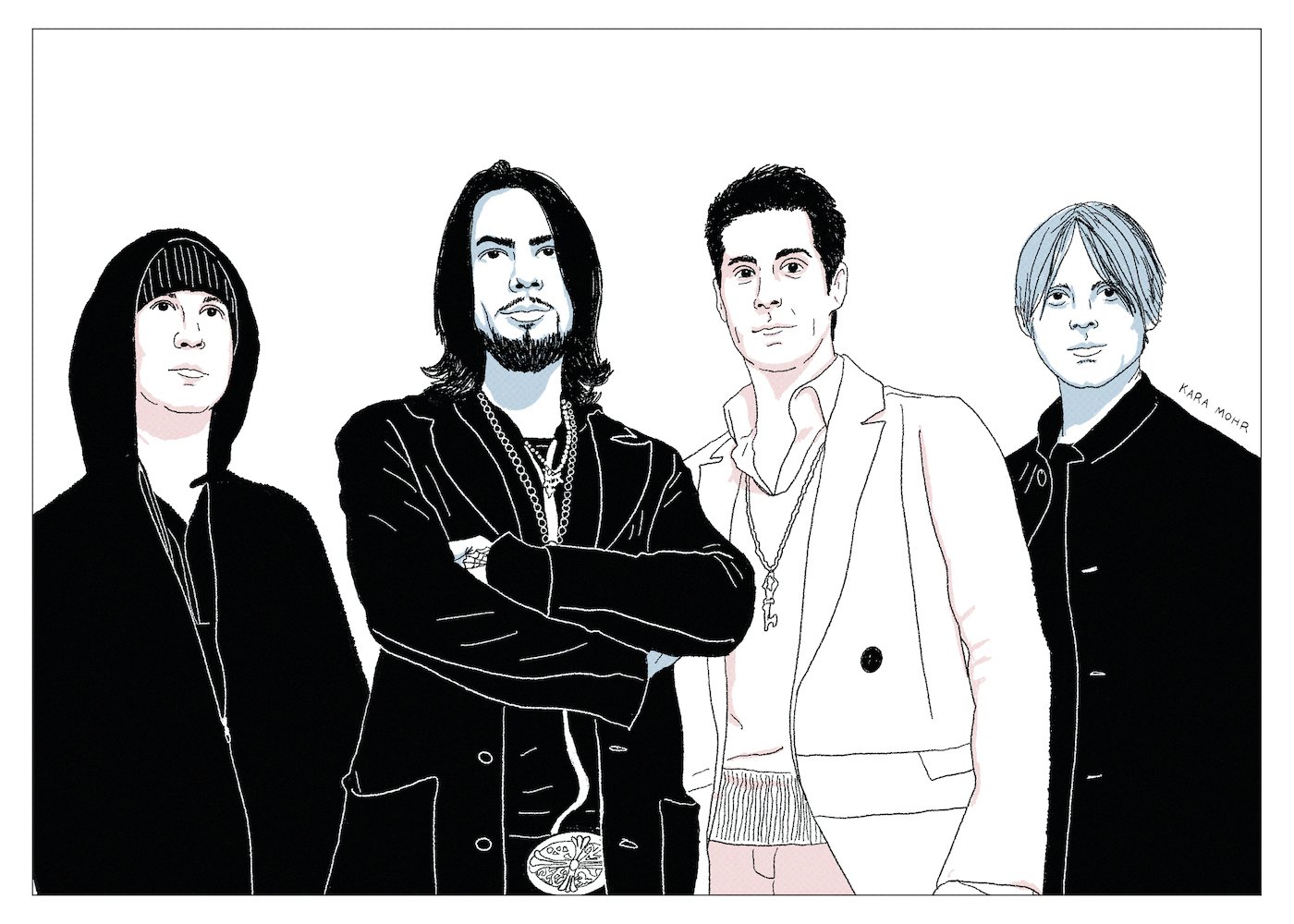

Jane’s Addiction “The Great Escape Artist”

By 2011, hell had frozen over enough that we began to expect the return of every legendary band. The Pixies, The Replacements, My Bloody Valentine, Pavement. The list was practically endless. It was simply too costly for those bands not to reunite. So, news of another album from middle aged Jane’s Addiction was kind of ho hum. For many, it was a curiosity, at best. At the core of this presumption was the belief that the great, unsustainable version of Jane’s had died in 1991. That they would return made only commercial sense. That they could recapture any semblance of their original brilliance made practically zero sense.

Beck “Hyperspace”

Since we finally met Beck, the grown up man, on “Sea Change,” a lot has happened: He got married. He had two children. He got divorced. He released seven albums -- most of them appreciated, and a couple beloved. He stayed in California. He stayed thin and pretty and a little weird. To the casual observer, he barely aged. But, with each successive album, he impressed less. There were no more “Odelays” or “Midnight Vultures.” In fact, to some fans and many critics, Beck became kind of boring. In 2002, I had firmly concluded that Beck could never be uninteresting. By 2019, however, I was less sure.

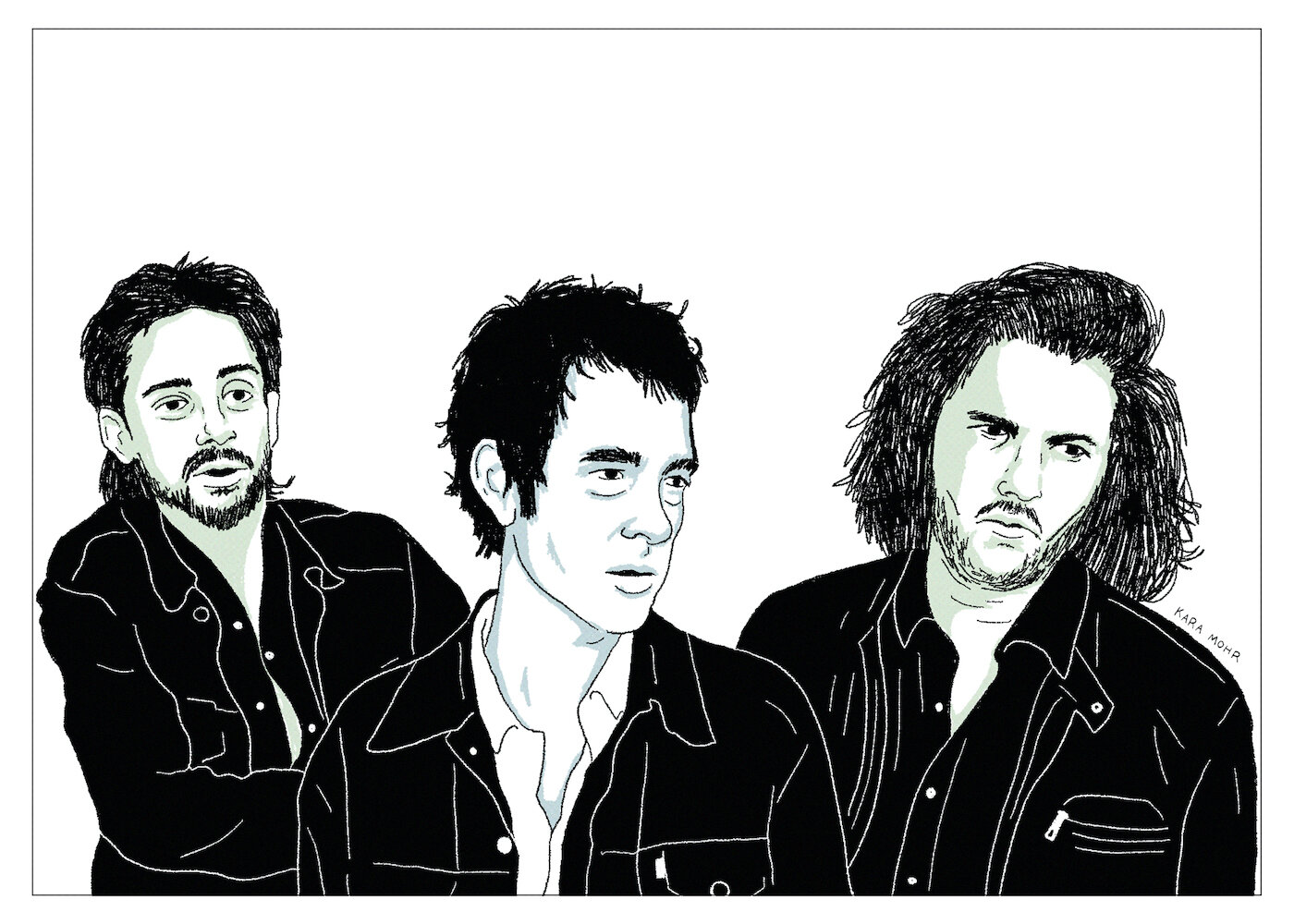

Jon Spencer Blues Explosion “Meat + Bone”

Right after Nirvana, but just before Radiohead, the Blues Explosion were the band that all of New York City wanted to happen. They emerged from the grime to make “Art&B” that was initially greasy, then sweaty and, eventually, glistening. But, slowly, and unexpectedly, the buzz quieted down. The albums got safer or weirder. A decade after their debut, they’d been market corrected by The White Stripes. In fact, they practically disappeared. But then, in 2012, they pulled the cover off the old muscle car, put the keys in the ignition and waited to see if the engine still ran.

David Kilgour “The Far Now”

What’s it like to be a treasure, buried deep inside an island halfway around the world? What’s it like to be a semi-legend who cannot make a living doing what you are revered for? What’s it like to be a middle-aged artist who means so much to so few, but absolutely nothing to so many. Eventually, David Kilgour, the darling, Kiwi uncle of Indie Rock, gave up worrying about these sorts of things. “The Far Now” is his exhale — the sound of sunrise and sunset.

The National “Sleep Well Beast”

In 2017, after a decade being carried in the arms of cheerleaders, The National were understandably disoriented. There was the scary new President. There was their unexpected stardom pushing up against their middle-aged domesticity. There was even a small, but vocal, backlash accusing them of sameness. And, possibly, smugness. “Sleep Well Beast” was the band anxiously experimenting their way through the quagmire. Meanwhile, I listened and wondered: can we ever go back?

The Feelies “In Between”

If ever there was a band that was born to disappear, it was The Feelies. They were the cult band that, for over forty years, were not a band much more than they were a band. They were R.E.M. without the feelings and Yo La Tengo without the romance. They wrote songs about nothing. They made four albums between 1980 and 1991 and then faded like Halley’s Comet. But then, twenty years later, they returned. And, even though they had already said everything that there was to be said about nothing at all, they kept on saying it. Same chords. Same mumbled words. And it was still perfect.

Wire “Change Becomes Us”

Wire was an argument against the zeitgeist. Anti-Rock. Anti-New Wave. Anti-Electronic. The alternative to Alternative. And, for decades, they despised nostalgia. They did not revel in the myth of “Pink Flag.” They were constantly present and stepping forward. But, what happens when the argument is futile? What happens when the future is gone? What comes after “posteverything”?