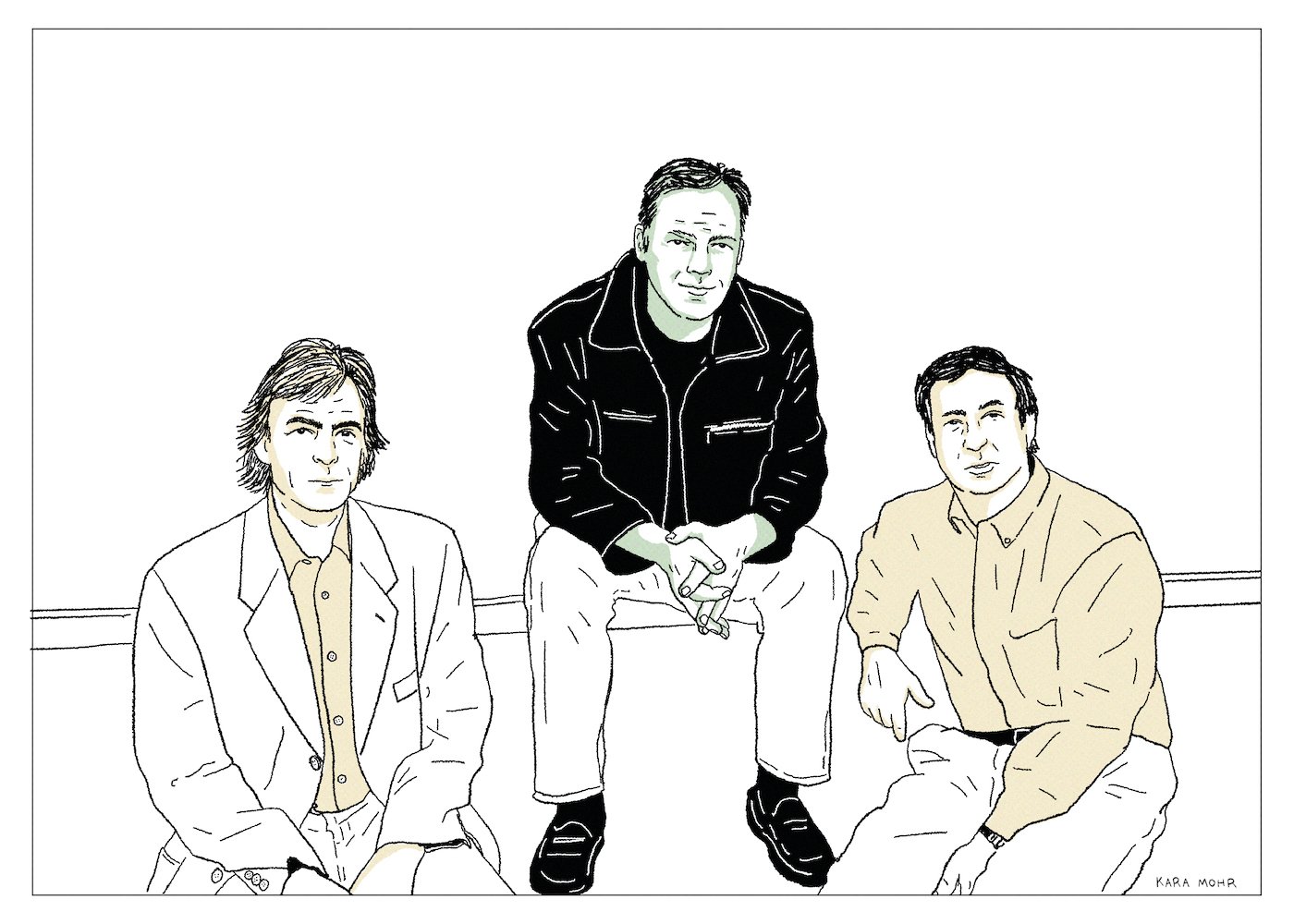

Pink Floyd “The Division Bell”

For as much as it was a David Gilmour album, “A Momentary Loss of Reason” was also a Roger Waters’ album. Every single review noted the absence of the band’s erstwhile leader, who was himself active and vocal in sharing his derision for the project. And while the record was commercially successful, it was doubly taxing. In its aftermath, Gilmore and Waters finally and painfully resolved most of their legal affairs but almost none of their enmity. For many years there was little hope, and no indication, of any future for Pink Floyd. But then, in 1993, the ink having barely dried on both his marital and professional divorces, Gilmour did something unexpected. He invited Nick Mason and Richard Wright—the latter of whom had been dismissed from the band during the making of “The Wall”—to get together, play some music and talk about the power of talking.

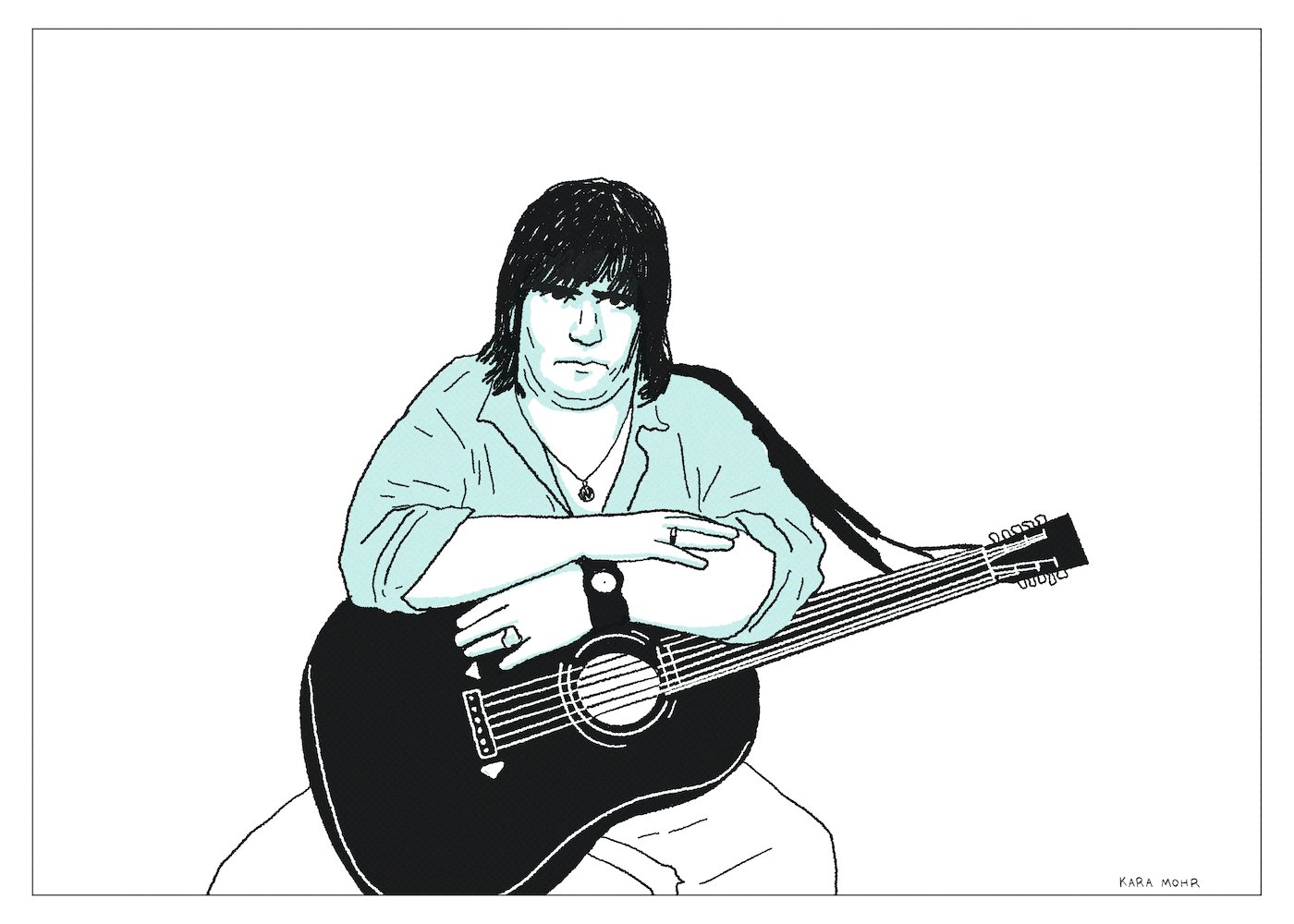

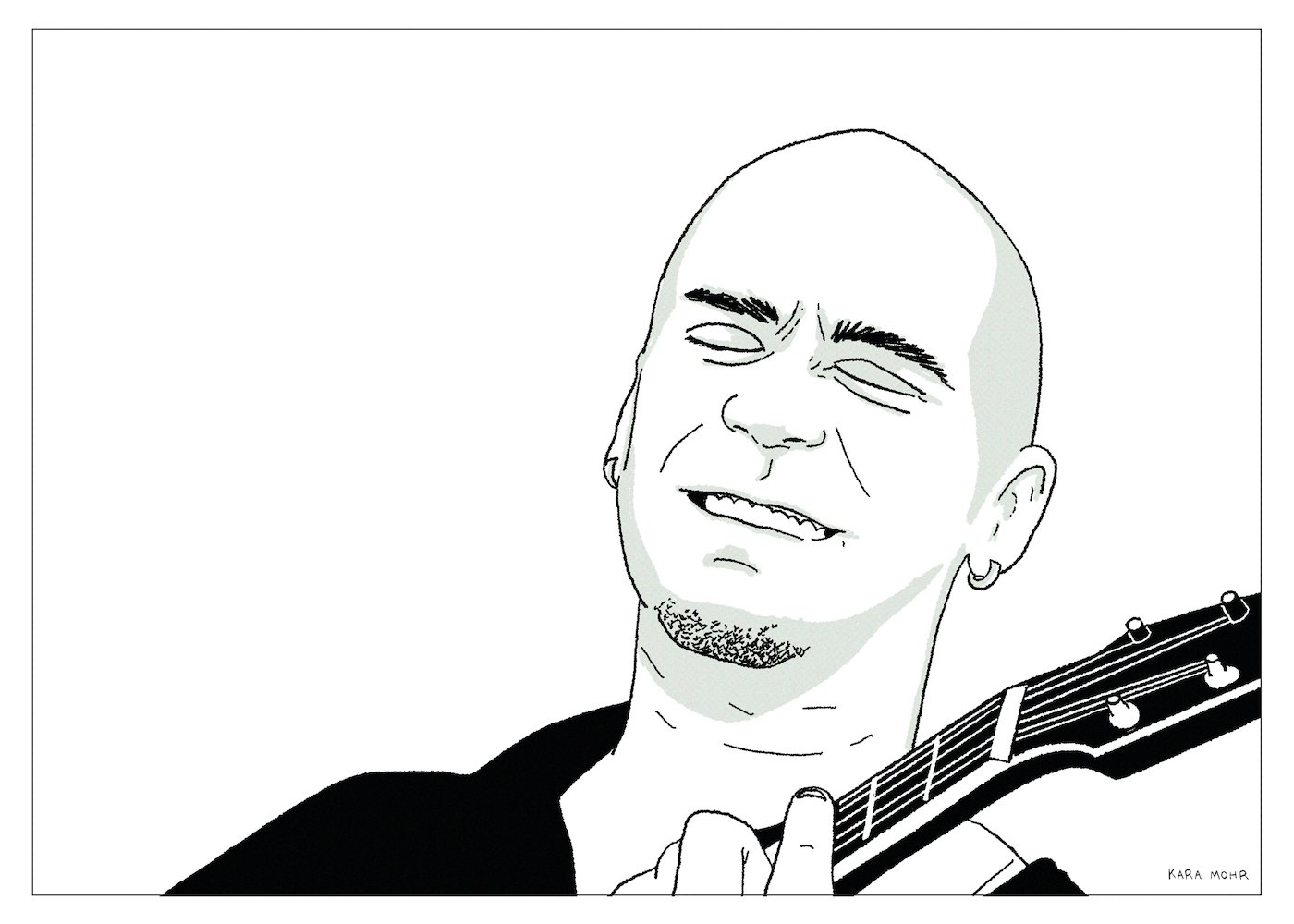

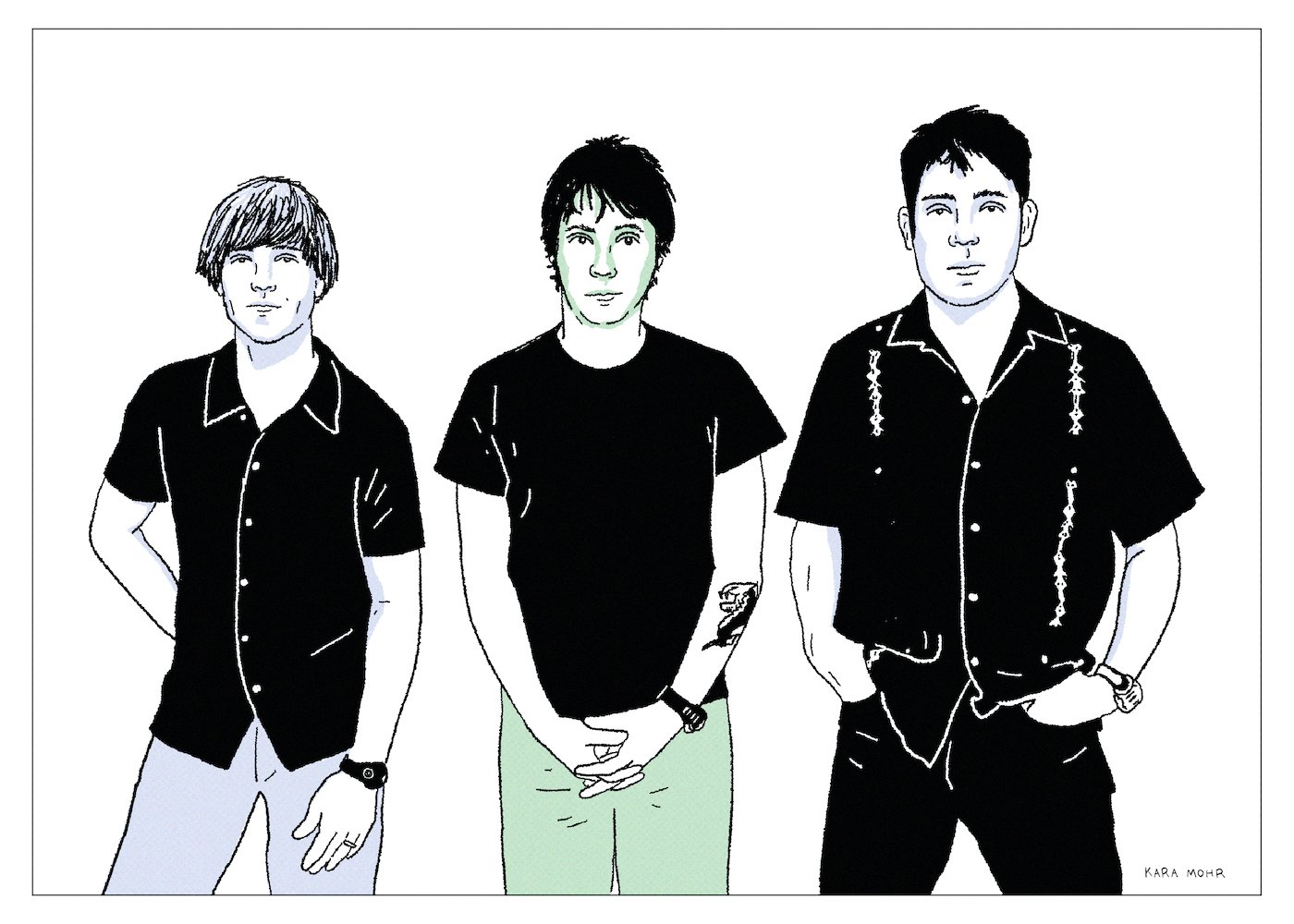

Steve Earle “I Feel Alright”

In 1996, having shaken off five years of rust, sixty days in jail and a couple decades of addiction, Steve Earle released “I Feel Alright.” Whereas 1995s “Train a Comin’” found him looking backwards, “I Feel Alright” was a completely present album. It was vintage Earle, after the pink cloud had dissipated—honest, aching, and feeling “alright.” Which is to say he was not feeling great. But also he was not feeling awful. It was a hedge—somewhere between cautious and optimistic. “I Feel Alright” is the ultimate one day at a time response to the question, “How you doing?” As a description of Earle’s state of mind, it sounds appropriate. As a title for his sixth studio album, it feels like a radical understatement.

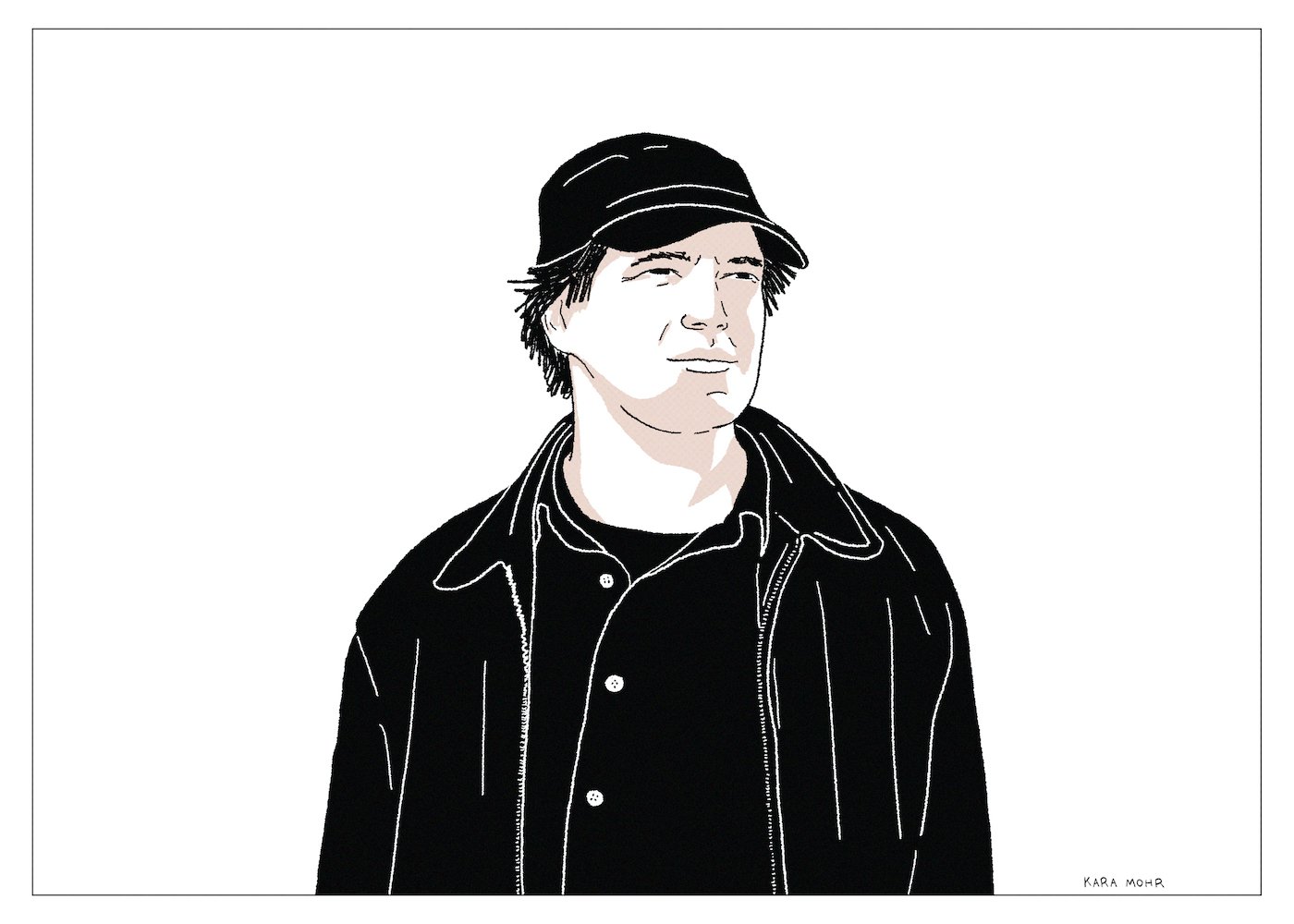

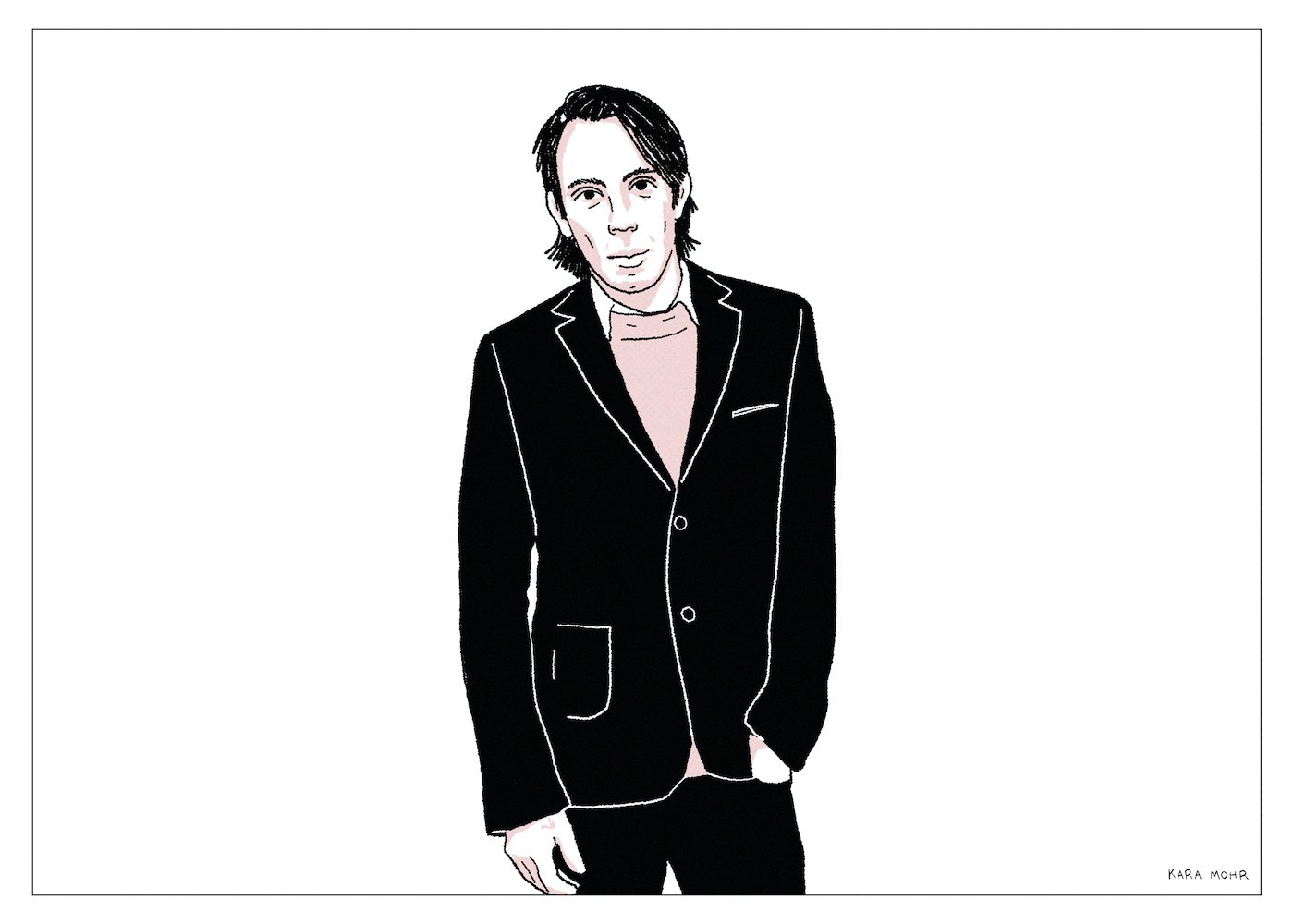

Richard Lloyd “The Radiant Monkey”

Following their unexpected reunion in 1992, Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine maintained a polite working relationship born from financial necessity and creative compatibility. The fallout from the first Television breakup had cost Lloyd a good deal of his commercial prime. The sequel, meanwhile, was a long, sputtering, part time concern. Lloyd made a small splash in 1991 for his appearance on Matthew Sweet’s “Girlfriend.” In 2001 he quietly released his first album in more than a decade. But, by 2007, he’d had enough. He’d had enough of waiting to make another Television record. He’d had enough of Tom being Tom. And so Lloyd finally resolved that—no matter how much he admired Tom Verlaine as an artist or even as a friend—he did not want him as a boss any more. Thirty-four years after he first joined the band and thirty-two years after he first quit the band and twenty-nine years after Verlaine broke up the band, Richard Lloyd quit Television and released “The Radiant Monkey,” his fifth solo album.

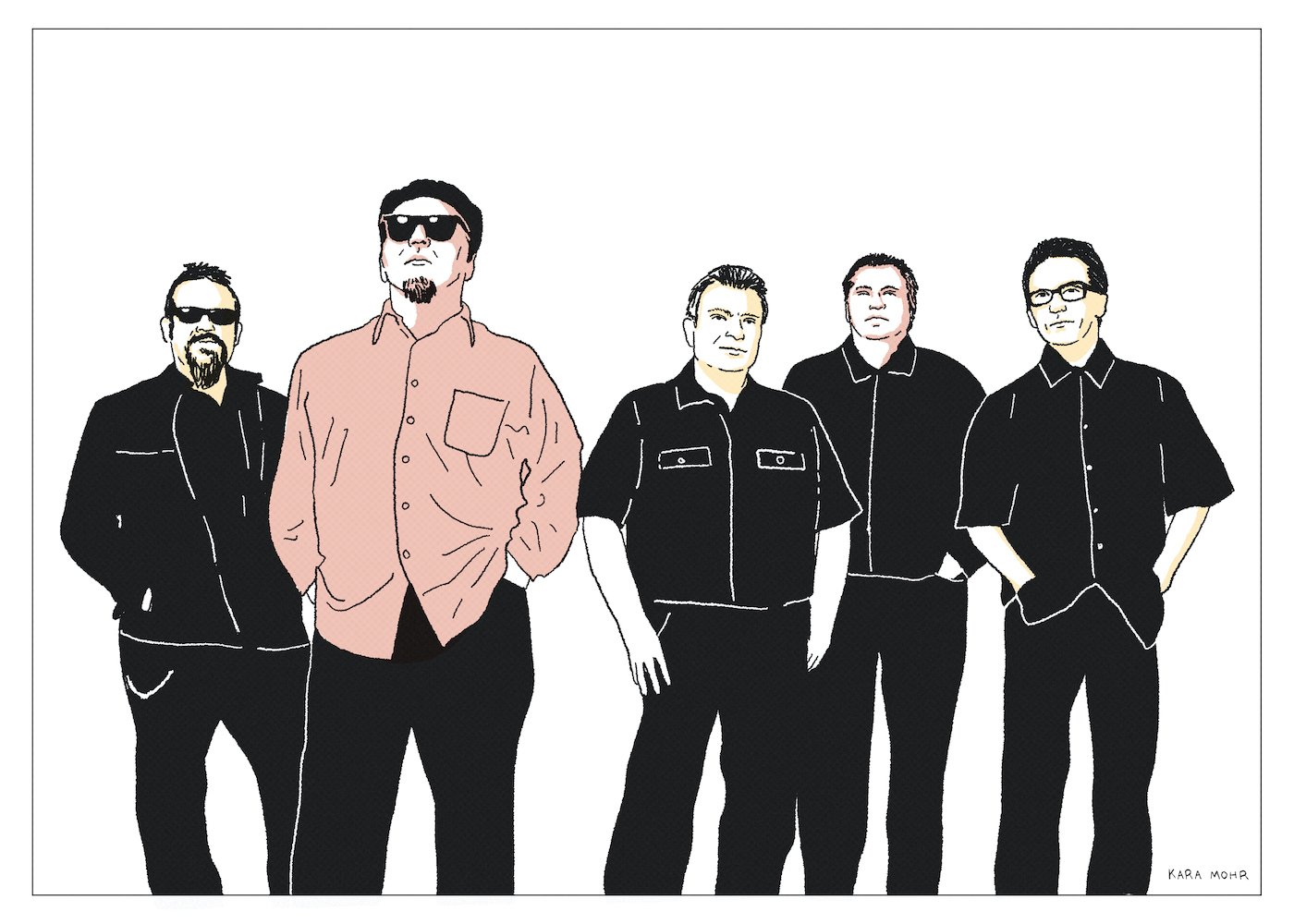

Asia “Phoenix”

If a computer—even a very old one—was tasked with naming an album made by the original four members of Asia who were reuniting for the first time in two decades, I am certain it would land on “Phoenix.” The metaphor of that ancient, immortal, mythological bird rising up again is simply too good to pass up on. “Phoenix” speaks to the passage of time, fire, beauty, erudition and regeneration. It is, in a single word, quite literally the perfect title for Asia’s comeback album—as ridiculous as it is accurate.

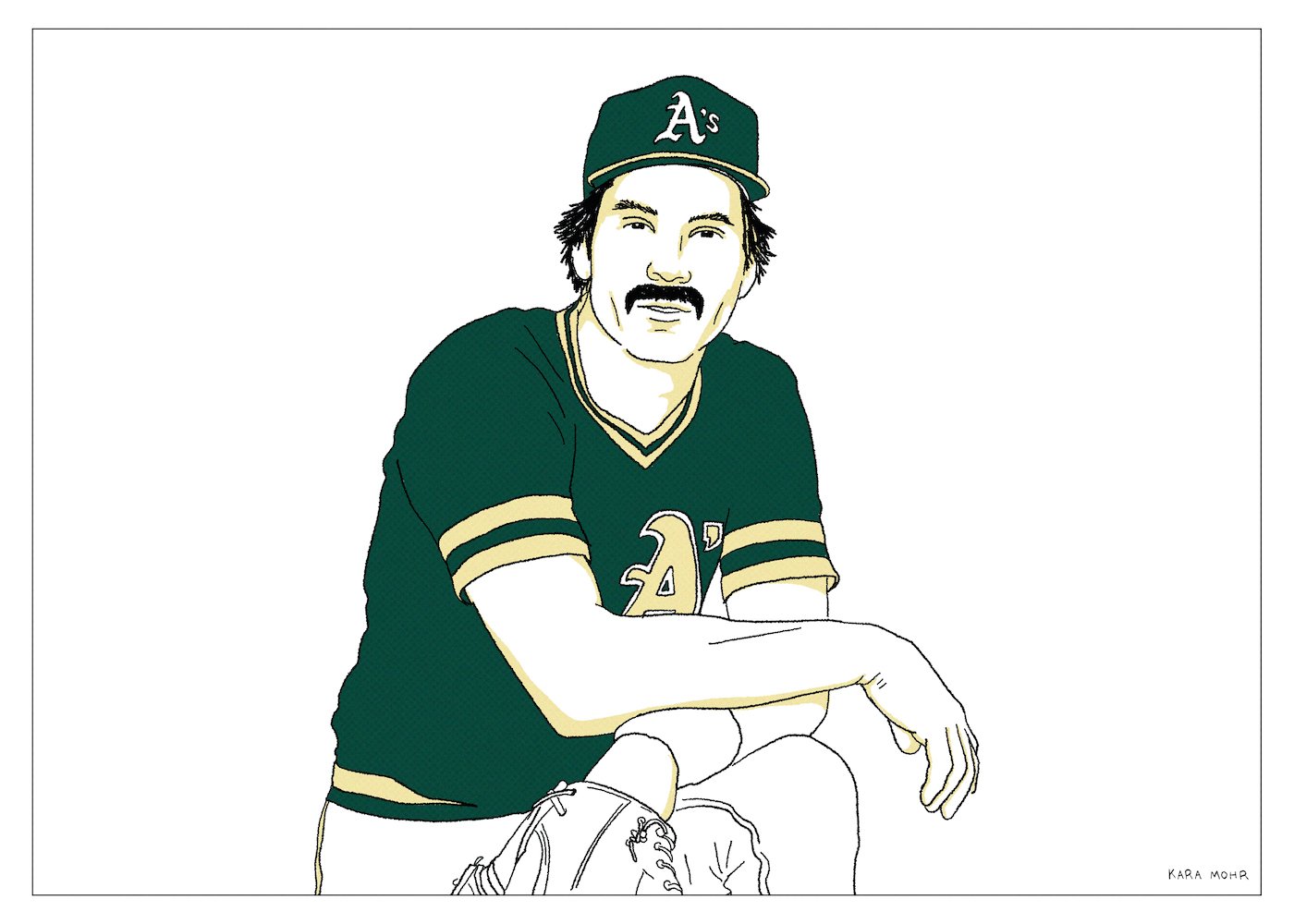

Dave Kingman “Kong”

Dave Kingman’s entire career—but especially his 1977 season, wherein he played his way off four different teams—suggests a dour, underperforming athlete who soiled each nest he landed in. However, beneath the surface of that framing is very different and equally viable narrative: Kong was rushed and forsaken—over and over again. He was a grown man—a superstar—every fifteen times at the plate and a helpless child the other fourteen times. George Foster, Garry Maddox, Gary Matthews and Bobby Bonds—Kingman’s teammates on The Giants in the early Seventies—all struck out much more than they walked. But none of them could destroy baseballs quite like Dave Kingman. And as a result, they were given time to practice, fail, practice, fail less, practice and—eventually—succeed. But not Dave Kingman. Everybody is awed by King Kong. But nobody roots for him.

Ed Kowalczyk “The Flood and The Mercy”

Today, Live is Ed Kowalczyk plus paid studio and touring musicians. Ed’s childhood friends—Patrick and the two Chads—were relieved of their duties after years of lawsuits, countersuits and shady dealings with a shady con man. Meanwhile, Kowalczyk, now a fifty-something, rat-tail-less, father of four, charms fans on Totally Nineties tours and delights deejays on retro adult radio formats. But in between “Alive,” Ed’s confusingly named solo debut, and his return to Live, he put out another solo album—a commercial failure and a critical “nope.” Middle-aged me had zero interest in this record. But seventeen year old me—the me who was still a work in progress, who was so open to new things and who’d convinced himself that Live were cool and deep and important—felt otherwise.

Boeckner “Boeckner!”

At just eight songs and barely thirty minutes, “Boeckner!” is closer to EP than LP. And if judged as an EP — the format which Wolf Parade chose to thrice introduce themselves way back when — I’d call it a success. A couple misses, a couple stash aways and four songs that justify the titular exclamation point. But considered as an LP, “Boeckner!” does feel a bit small. Or rather a little short. Which sends me back to Joe Strummer — Boeckner’s spiritual forebear and the most important guy in the most important band in the world who never had the will or the want or the whatever to be that guy outside of The Clash. As magnetically cool and as evidently smart and talented as he might be, Boeckner — like Strummer, like most of us — needs a partner. Twenty years with Spender Krug. A glorious season with Britt Daniel. Five plus years with Alexei Perry. And, for nearly decade with Devojka, Boeckner’s bandmate in Operators and co-writer on half of “Boeckner!”

Billy Joel “Turn the Lights Back On”

Billy had been stashing away ideas for years — parts of melodies, little hooks, half bridges, hummed choruses — but could not, would not complete a song. And so, rather than push him to the brink, Freddy Wexler politely requested to check out some of those song scraps. And eventually, through a combination of talent, elbow grease, Wayne Hector and Arthur Bacon, “Turn the Lights Back On” was born. The story is vague enough to be true. But it is also vague enough to make me ask, “Did Billy write the song at all?” The more I considered it, the more plausible it seemed that a very smart AI might have produced “Turn the Lights Back On.” Maybe Billy Joel’s new single was an AI deep fake. Maybe its perfection was actually an uncanny valley.

Los Lobos “Native Sons”

Over the course of nearly fifty years and seventeen studio albums, Los Lobos have been many things. A wedding band. A Rock band. A Folk band. A Punk band. They’re omnivores — multi-instrumentalists, songwriters, radical interpreters and loyal cover artists. Their influences are as diverse as their influence — members of the band have appeared on records from pretty much every legend who's passed through Los Angeles since 1980. From Bob Dylan to Eric Clapton and from Dolly Parton to Bonnie Raitt. Like their hometown, Los Lobos are diffuse. And like their hometown, they are Mexican. Which is why, more than anything, Los Lobos are underestimated. Pop music comes in many forms, but it gravitates to the specific and the English. Meanwhile, Los Lobos’ greatness lies in the fact that they are almost the complete opposite of those things.

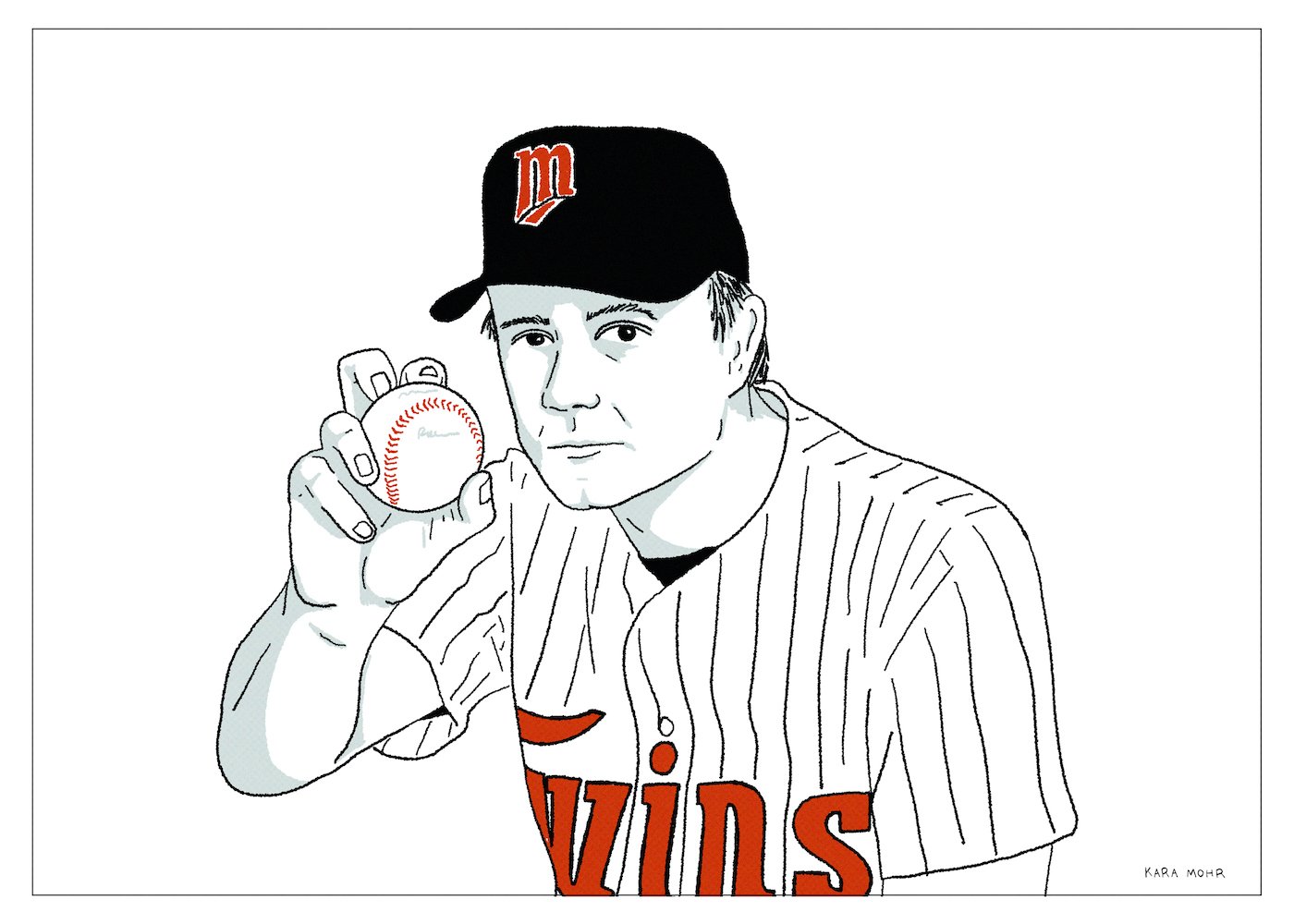

Joe Niekro “Do I Look Like a Doctor?”

For twenty plus seasons, and with the possible exception of Gaylord Perry, no pitcher doctored a baseball like Joe Niekro. Despite two decades of skirting the rules, though, Niekro was caught just once, in 1987 when he was tossed from a game by umpire Tim Tschida. Niekro’s ball doctoring was a long held, open secret that players, managers, umps and even fans were complicit in. But why? Why did we offer him such radical empathy? Perhaps because, in time, we all watch people around us become Joe Niekro. We ignore mild transgressions against nature in some sort of communal fight against aging. It’s only when it becomes too transgressive — when emery boards go flying or the third face lift becomes too difficult to look at — that we find our our collective, inner Tim Tschida and start moseying up to the mound.

Fastball “Little White Lies”

Nada Surf, Superdrag, Fountains of Wayne, Harvey Danger, Semisonic. There is a cohort of Modern Rock bands from the Nineties who made off-kilter Power Pop and who became briefly, somewhat famous. But Fastball was different in that (a) they were more than just somewhat famous and (b) when they faded, they plummeted. Moreover, unlike their peers, Fastball was not retrospectively considered under-appreciated. In fact, they were hardly reconsidered at all. Fastball never had a second act as prestige artists on an Indie label. Never had a third act as songwriters to the stars. They just — and just barely — kept going, writing great songs and making very good albums.

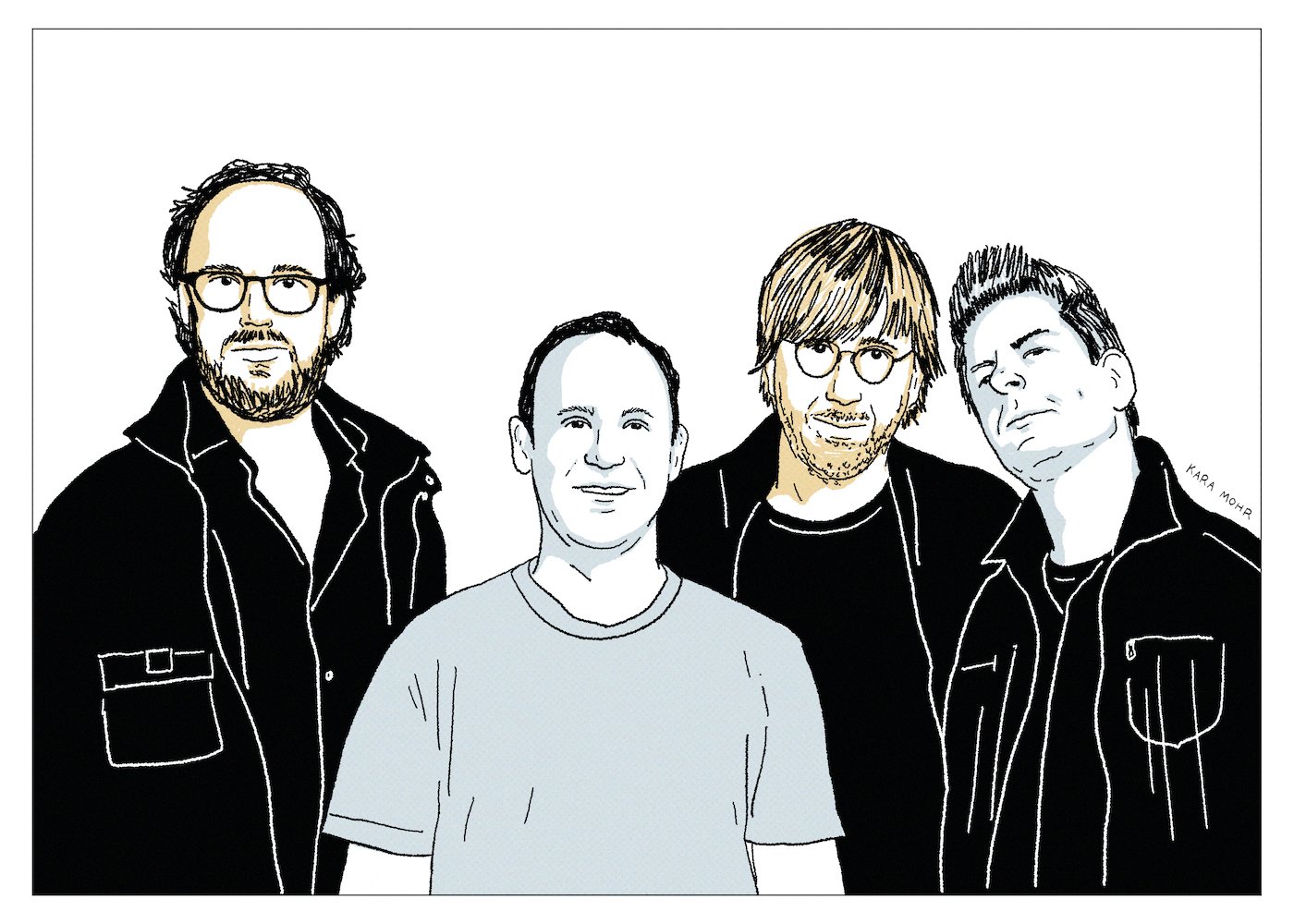

Phish “Fuego”

I have a Phish problem. Or at least, for the last thirty years I’ve told myself that I have a Phish problem. This problem is in spite of my adoration for the state of Vermont. In spite of my having seen Phish perform live multiple times. In spite of being occasionally, but earnestly, wowed by the wizardry of their jams. In spite of my appreciation for their business acumen. In spite of my loving their Ben & Jerry’s flavor. Yes — in spite of all of it — I don’t abide. Which, for most people, would not be such a problem. But, as a Vermonter at heart, I am left with this unrelenting pull between my Yes-Vermont soul and my No-Phish conscience. It is a battle that, until recently, I had ignored. But it was a battle that I knew — someday, somehow — I’d need to resolve.

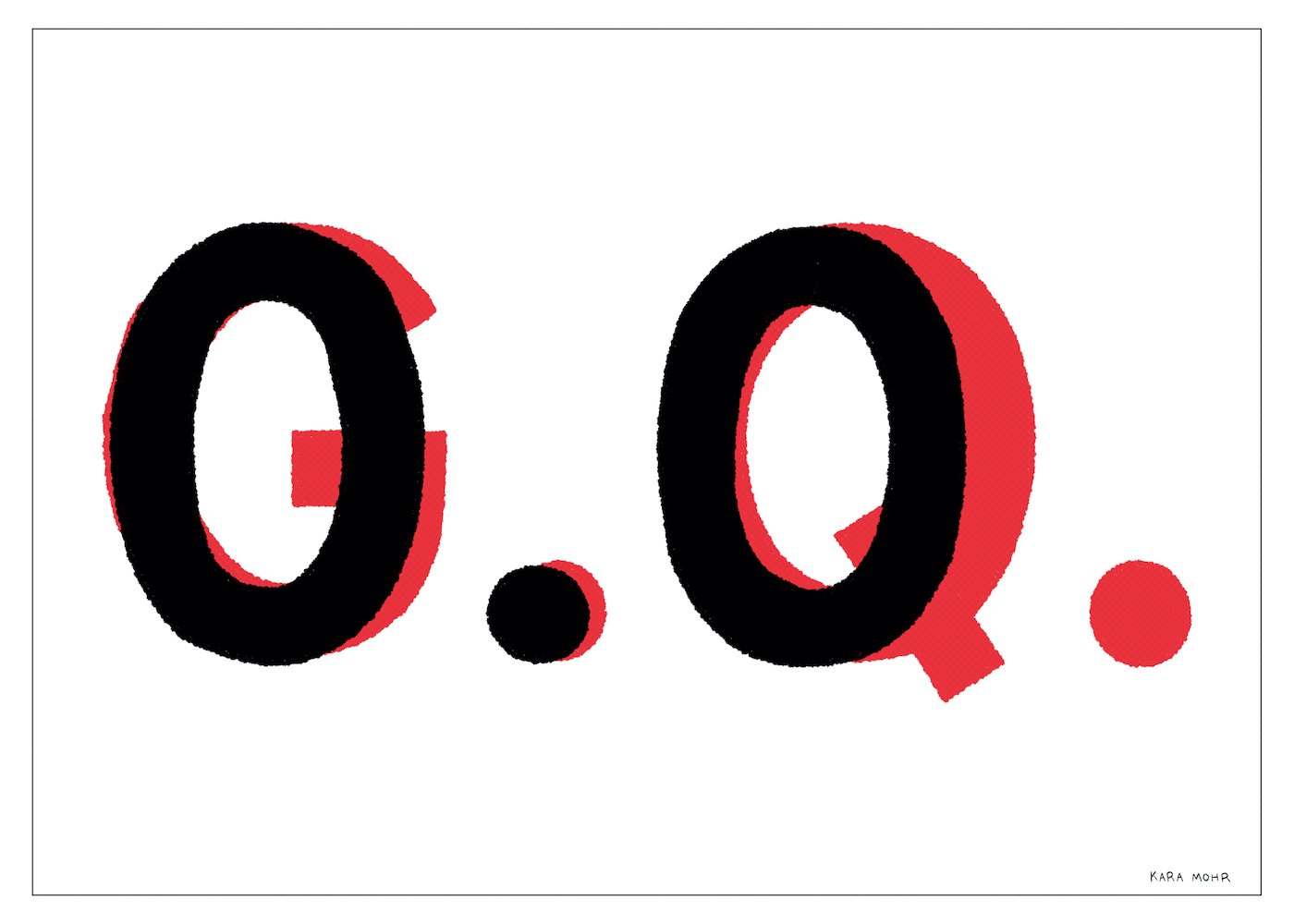

Pitchfork “0.0”

It’s been a couple of weeks since Condé Nast’s decision to reorganize and downsize Pitchfork, a move that drew head scratching disbelief and foot stomping ire from everyone with an opinion on the matter. As with all corporate shake-ups, the full implications won’t be understood for some time. But what is knowable now, and for certain, is that (a) many people lost their jobs and (b) Pitchfork was one of the first Condé Nast titles to successfully unionize and (c) the writing at Pitchfork was never better than it had been recently, under Editor & Chief, Puja Patel. Meanwhile, what should have been known to Anna Wintour (Condé Nast Chief Content Officer), Roger Lynch (Condé Nast CEO) and Nick Hotchkin (Condé Nast CFO), is that nobody under the age of fifty gives a shit about G.Q. (the title that Pitchfork was reorganized into) and that many people give many shits about Pitchfork.

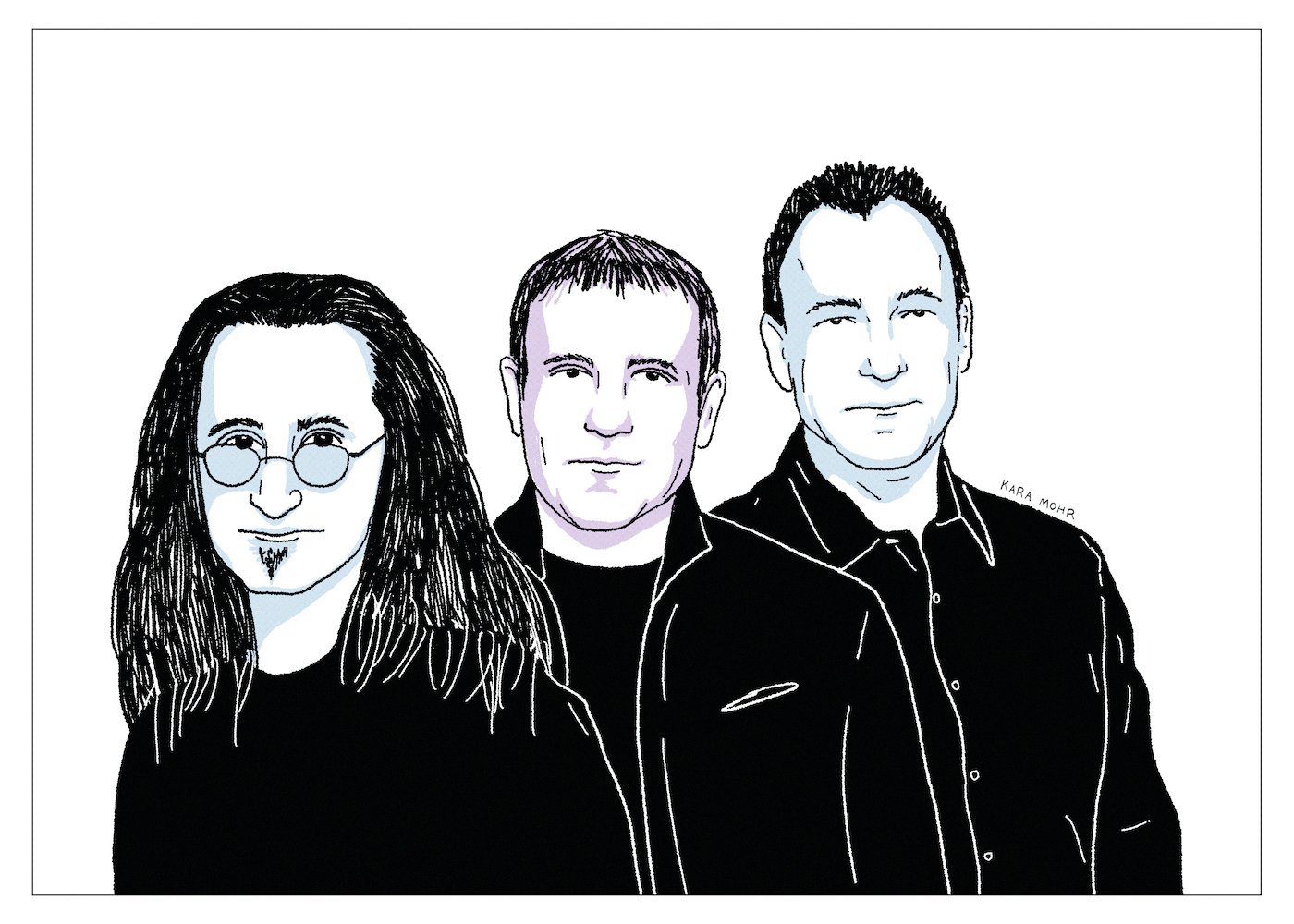

Rush “Vapor Trails”

By the time I reached middle age, my longstanding, polite refusal of Rush had settled into a wizened indifference. In fact, since I was not a subscriber to Guitar World or Drummerworld magazines, many years would go by without me hearing a peep about the band I’d once tagged “Loser Van Halen.” But then, one day, I caught wind of “Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage,” a documentary that was generating buzz on the festival circuit. That buzz swelled, culminating in awards, which begot a short theatrical run, which is where, in the summer of 2010, I was confronted with the most unfathomable of questions: What if the band I liked the least was the one I loved the most?

Bry Webb “Run With Me”

Some bands are corporations, like The Rolling Stones. Some are communes, like Big Thief. Some are gangs, like The Clash. The Constantines, however, were more like a union — the genuine article. They were brothers in arms, in jeans and flannel. But when their mission inevitably bumped up against the realities of family and finance, the union dissolved. The miracle was not that The Cons broke up. The miracle was that they were so true and so committed for as long as they were. Just four albums. Not even a decade. But they never stopped waving the flag. Never stopped working. Which is why Bry Webb needed a break. Why, first, he left for Montreal. And then to Guelph, outside Toronto, where he started anew — as a husband, a college radio programmer and the maker of quiet, plaintive songs about the glow and glare of new fatherhood.

Kevin Drew “Aging”

Since “You Forgot It in People” — the record that a generation made out to and broke up to — every Broken Social Scene album has been an event. The reveal of who’s in and who’s out and the inevitable comparisons to their masterpiece. But while they have all been events, they have been more so celebrations. For all of the gothic romance of “Lover’s Spit,” Kevin Drew sure seems like a jubilant fellow. “Hug of Thunder” is his brand. He’s the glue and the vibes. But he’s also a guy who exists outside of his collective. In between those BSS records, Drew has been releasing lower stakes solo albums. Initially, with many members of Broken Social Scene. Then with a few. And then, finally, all alone.

Ron Guidry “Gator Wrestling”

Sandy Koufax famously retired at the age of thirty, while still at the top of his game. To fans, his exit was abrupt, but graceful — the definition of an athlete leaving on his own terms. Ron Guidry was the opposite. While his career stats were almost interchangeable with Koufax’s, and while their peaks were similarly untouchable, their retirements were a study in contrast. After a stellar ‘85 season, wherein he won twenty-two games, led the league in winning percentage and finished second in the Cy Young award, Guidry faded. Injuries started to mount. Shoulder. Then elbow. Surgery was required. Rehabs were long. Every step forward felt like two steps back. Until, eventually, Gator was down in AAA, waiting for the call and wondering if he’d ever pitch in the majors again.

Coldplay “Music of the Spheres”

And that was the thing about Coldplay — they were fine. Extremely so. But, also, just so — fine. Their bug — a complete lack of tension — had become their undeniable feature. Even in divorce, Chris Martin managed to avoid friction, co-describing his split from Gwyneth not as a divorce or a break-up, but as a “conscious uncoupling.” However, where their consistency was once considered a strength, in time people began to whisper about their boring sameness. At the height of their ascent, Martin had quipped that Coldplay needed to focus on getting better, not bigger. By the second decade of the twentieth century, however, they were neither better nor bigger. They were more hovering blimp than soaring rocketship.

Night Ranger “Somewhere in California”

What happens to our dreams in middle age? Do they still matter? Were they silly to begin with? These are the questions we wrestle with on the other side of forty. And, as much as Night Ranger were an Eighties Rock band, they were also a middle-aged Rock band. Strictly speaking, they were more the latter than the former. While they released five albums during their heyday, they — amazingly — have put out eight albums since. Their most recent album, from 2021, was “A.T.B.O.,” an acronym for “And The Band Played On.” Its predecessor, from 2017, was entitled “Don’t Let Up.” The evidence suggested that Night Ranger wasn’t simply “hanging on.” That they were not content being “the Sister Christian guys.” That there was a destiny yet to be fulfilled.

Barry Manilow “Here at the Mayflower”

Barry Manilow has sold more than eighty-five million albums — that’s more than Tom Petty, Nirvana or KISS. Once upon a time, he was the yellowing wallpaper of American music. For the better part of a decade, his songs were all over the radio, in grocery stores, waiting rooms and elevators. But, by 1984, years after “Mandy,” he’d hit a wall. Yes — the man who wrote the songs (but who I later learned did not write “I Write the Songs”) stopped writing the songs. After “2:00 AM Paradise Cafe,” it would be another twenty years before Manilow produced another album of originals. When he did, though, it was a doozy. “Here at the Mayflower,” from, 2004, was the apotheosis of Barry Manilow — an album of Swing, Mambo, Pop, Disco and Cabaret tunes about the apartment building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn where he grew up. It was the record that Terri Gross and Oprah Winfrey desperately wanted. It was the concept album he was born to write.