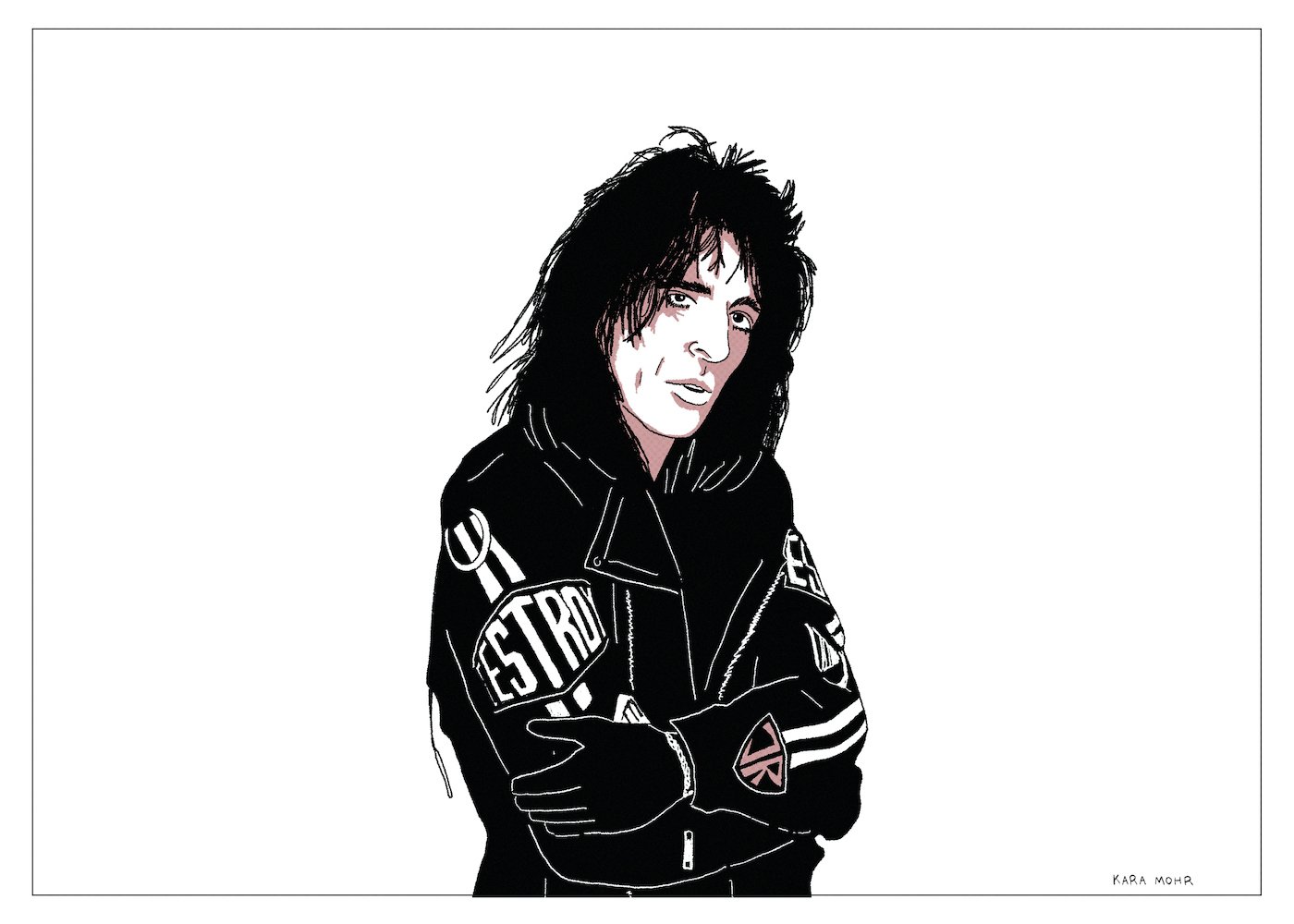

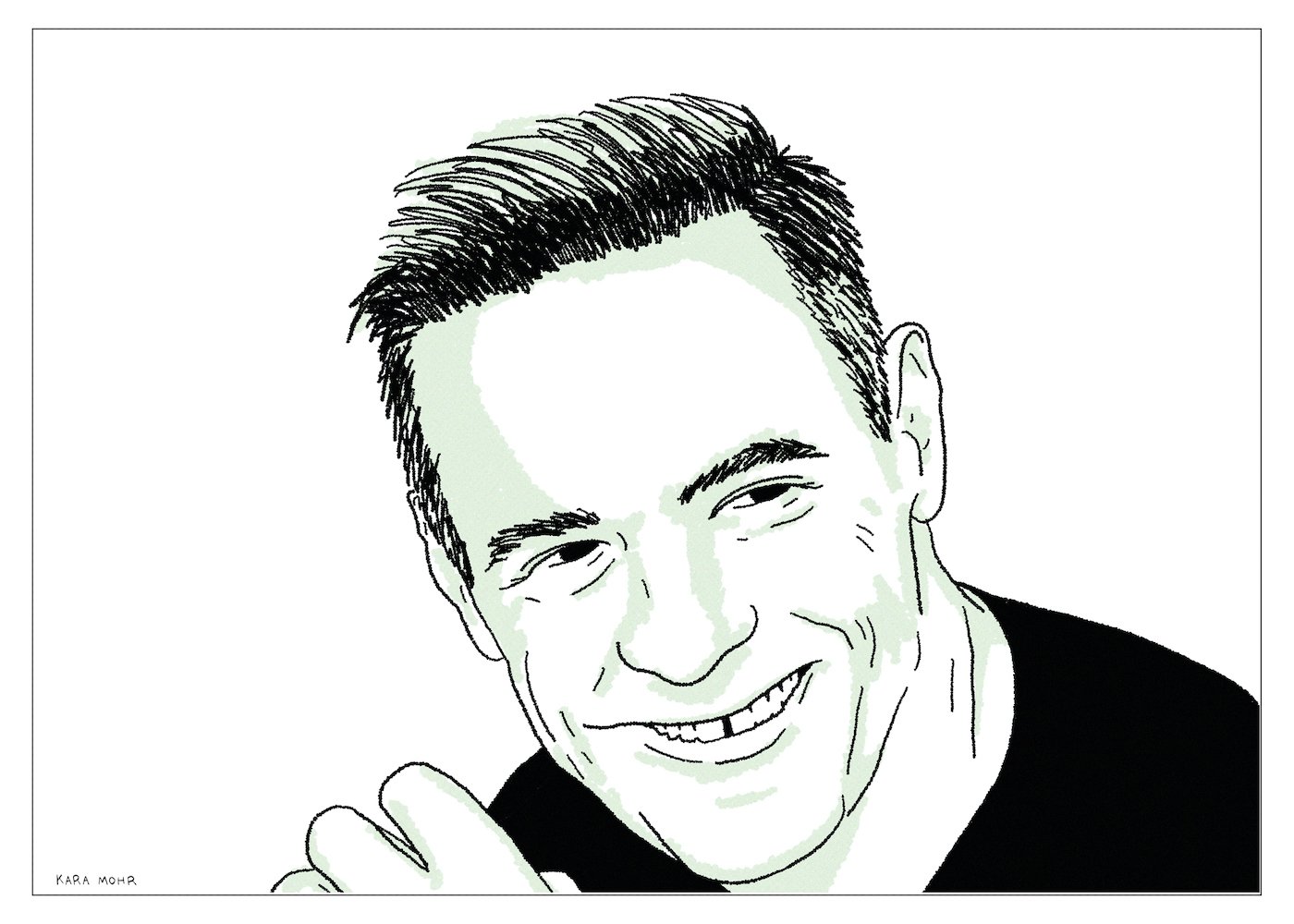

Alice Cooper “Trash”

The early 80s were not kind to Alice Cooper. Sober, but restless, he tried new gimmicks. He brought more snakes onstage. He tried his hand at New Wave. He traded booze for golf. But nothing seemed to work. By the mid-80s, while Hair Metal — a genre that he’d in part given birth to — was ascending, Alice Cooper was nothing more than a charming “has been.” But then, when it seemed that he was all past and no future, he caught a massive break. Desmond Child, a longtime fan and, more importantly, the super-producer of gargantuan, shout-along hits by KISS, Bon Jovi and Aerosmith, offered to help the forty year old, Shlock Rocker reclaim his throne. In order to succeed in the mission, Child had one requirements. He demanded that Cooper sing about the one thing that all teenagers are obsessed with but which the future GEICO spokesman had somehow avoided for his entire career: Sex.

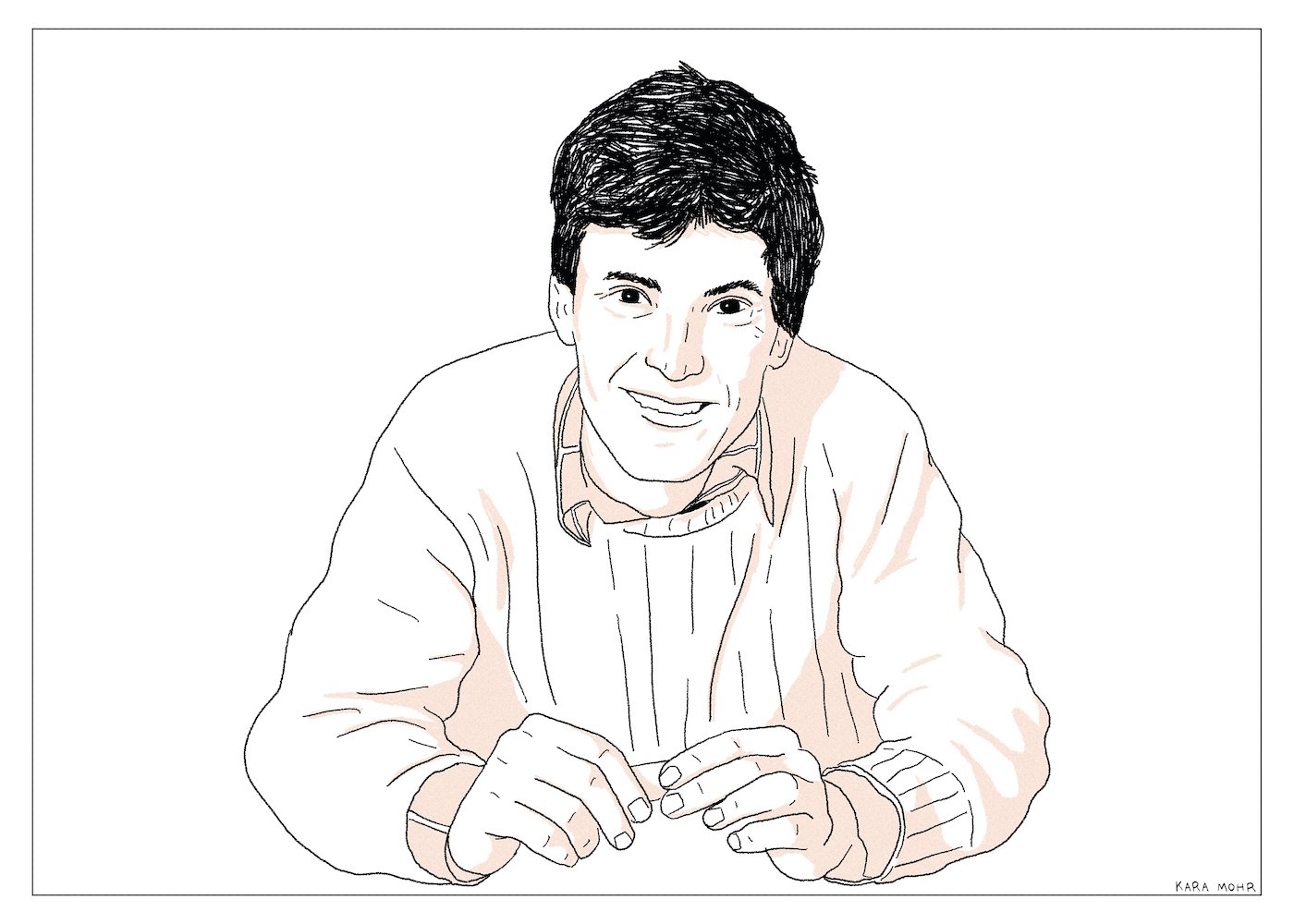

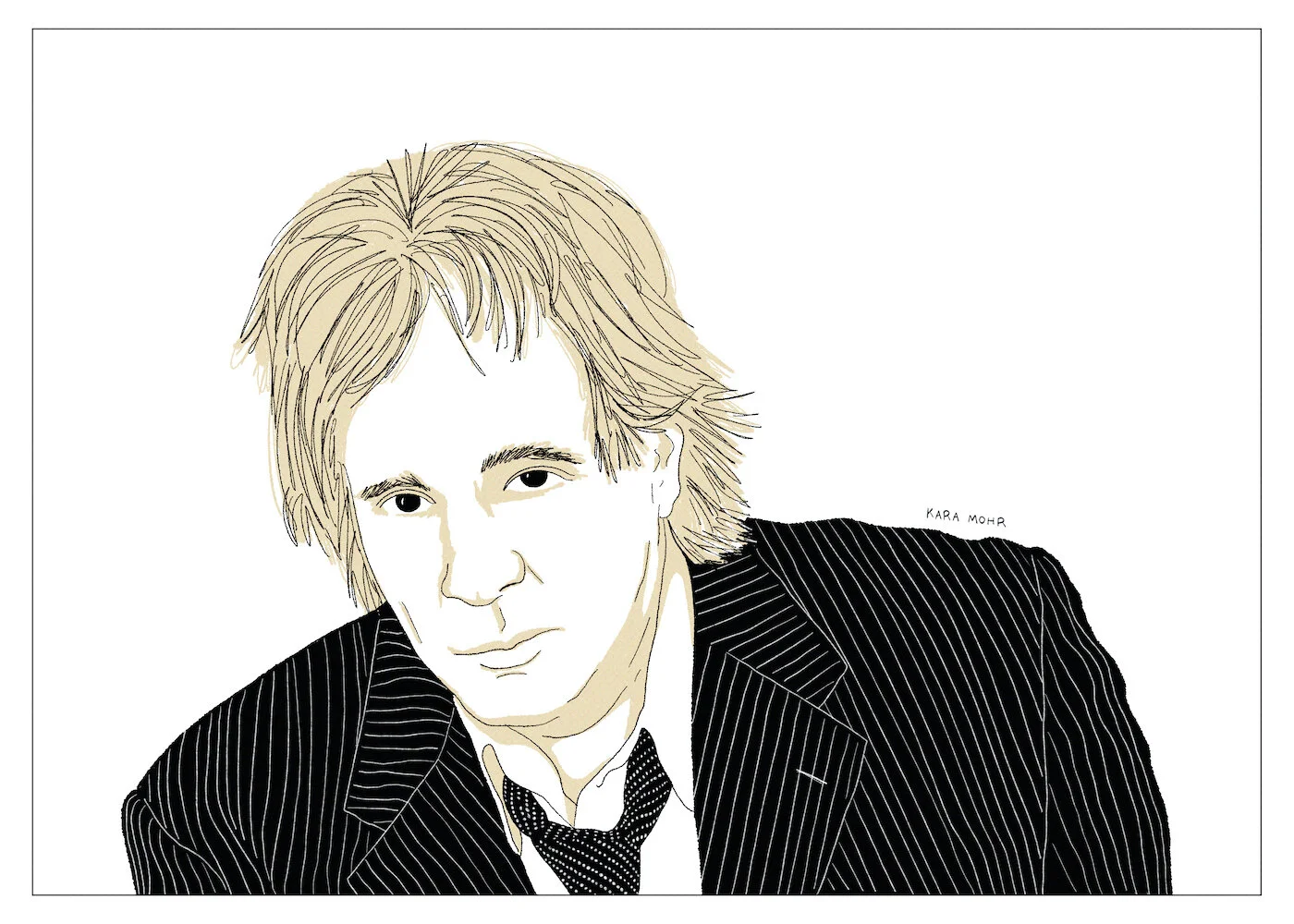

Art Garfunkel “Scissors Cut”

From 1970 through 1973, Art Garfunkel was among the most fascinating men in America. Coming off of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” he turned his attention to acting, where he made his debut in Mike Nichols’ “Catch-22.” The next year, he was nominated for a Golden Globe for “Carnal Knowledge.” Eventually, though, he reemerged as a solo recording artist. “Angel Clare,” from 1973, produced two top forty singles, and a series of Gold and Platinum-selling albums soon followed. What began as warm possibilities, however, devolved into flaccid melodies and artistic stagnation by the end of the decade. And then, tragically, Garfunkel’s romantic partner of many years, Laurie Bird, committed suicide in 1979. Most of America was depressed in 1979, but Art Garfunkel was more depressed. 1981’s “Scissors Cut” is the evidence of that depression — a bawling, private eulogy, pressed onto vinyl. It was also the end of “Art Garfunkel, Pop Star.”

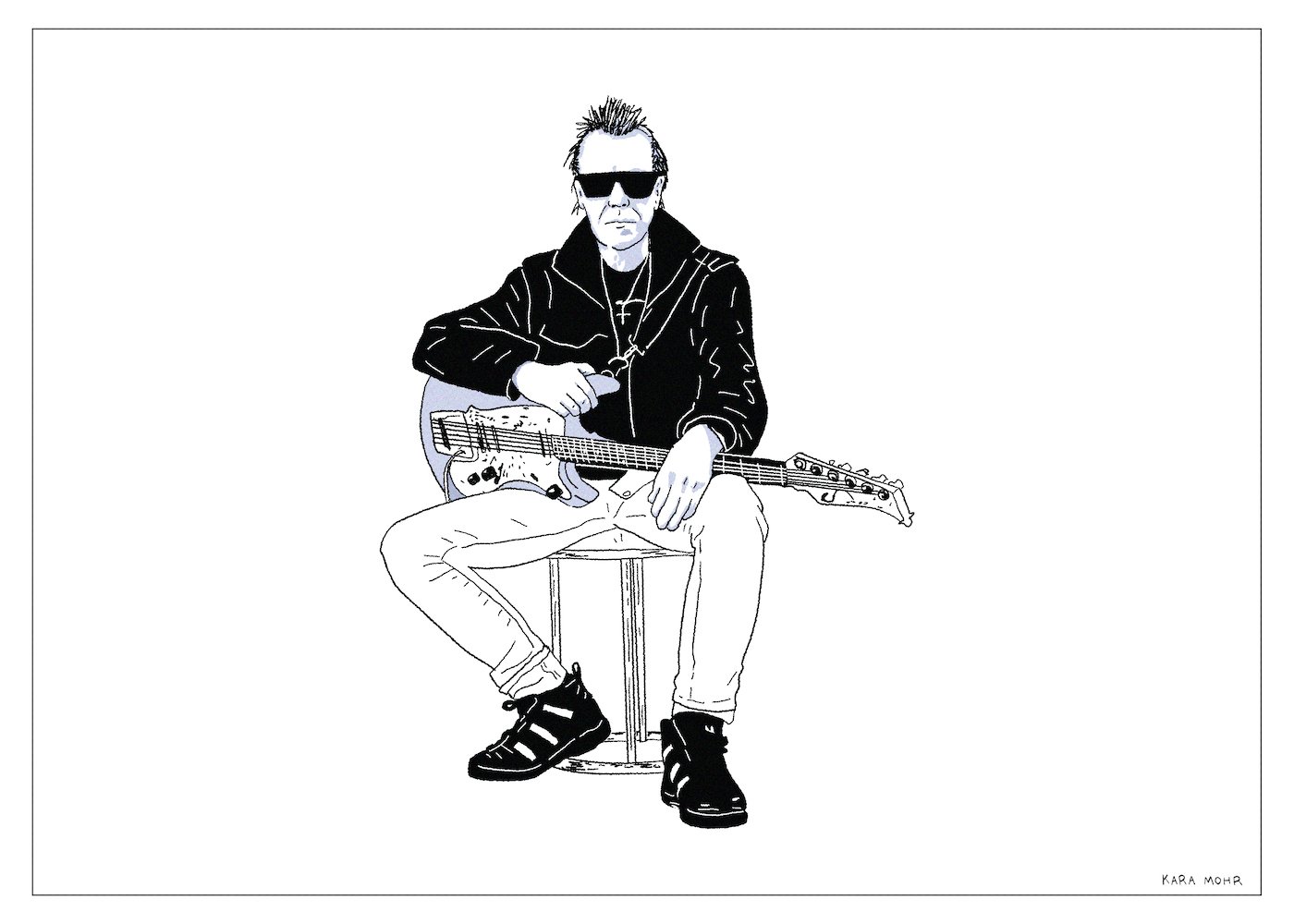

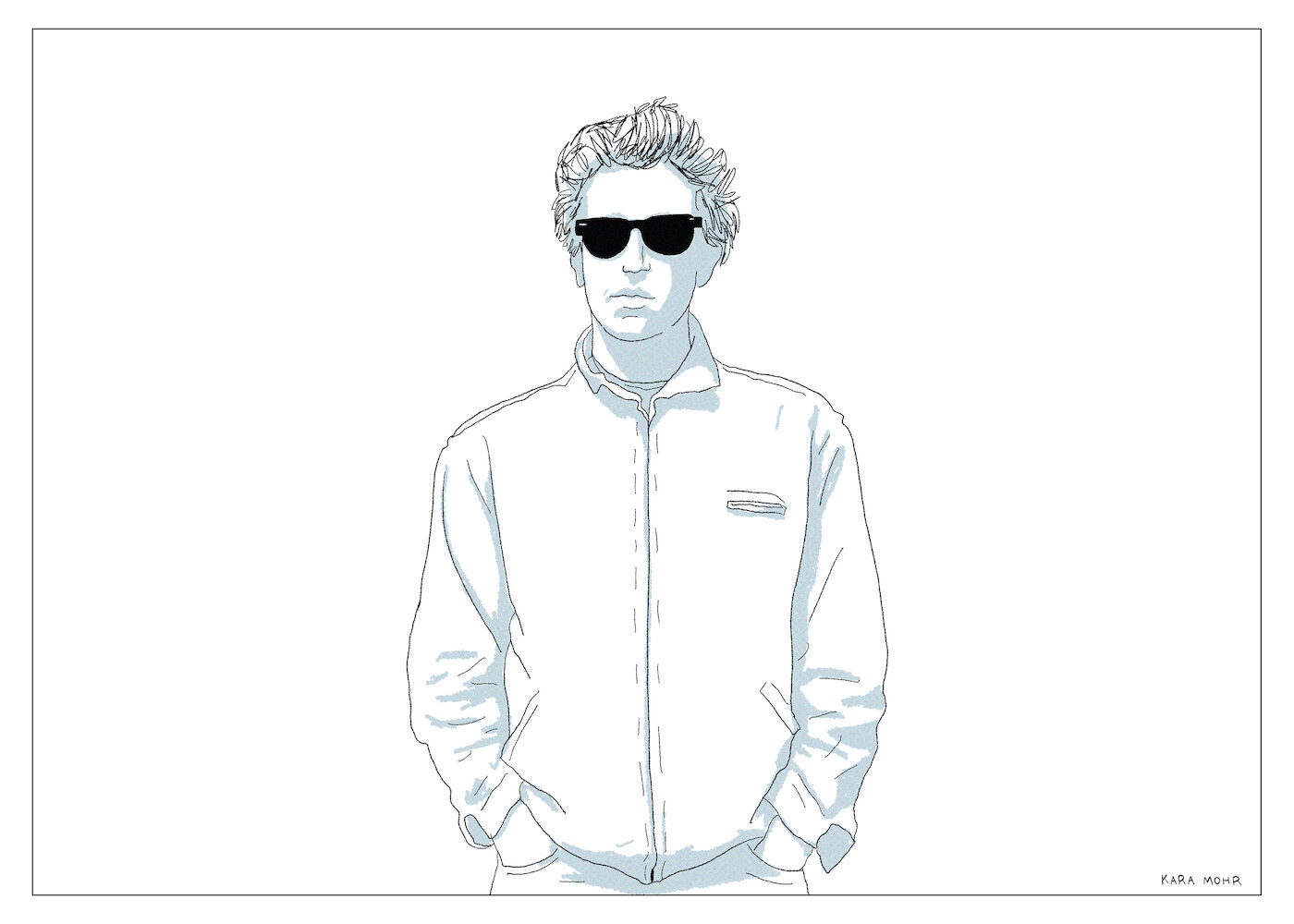

Link Wray “Barbed Wire”

After a dormant decade living a quiet life on a remote island in Denmark, the man who’d invented Hard Rock discovered his new sound. Amazingly, sixty-something Link Wray was faster, louder and scarier than his younger self. Whereas “Raw-Hide” and “Rumble” were soundtracks to noirish Westerns, his final performances sound like The Replacements scoring a 1950s drag race. Flanked by a band of much younger devotees, Grandpa Link returned to salvage his legacy. In spite of his indisputable greatness, he’d failed as a pop star. Failed as a folkie. And failed as a proto-punk. So, this time out — his last time out — he opted for all three incarnations. He wore black sunglasses, a leather jacket, a white tank top and a two foot ponytail and a thinning pompadour. He looked as though he’d either lost his mind or that he meant business. Or possibly both.

Ric Ocasek “Nexterday”

Ric Ocasek’s life after The Cars included a series of charming, lower stakes solo albums in between gigs as a “record guy.” For most of the 90s, he was a talent scout for Elektra Records and an elite producer for hire. But with Weezer’s “Blue Album,” Ocasek graduated from producer to “super-producer” — which meant he could do whatever he wanted, including making albums for Le Tigre and Brazilian Girls. It also meant that he could write poetry and paint and be the husband of a supermodel. He trimmed the New Wave mullet an inch or two, and maybe he added some lines to his face, but he still hid under the shades and bangs. He still wore oversized tops, buttoned all the way up. And he still had that odd earring dangling. In contrast, by 2005, Blondie was a nostalgia act. David Byrne was more high art than Pop. Sting made listless world music. And Duran Duran survived through the wonders of modern medicine. But Ric Ocasek, it seemed, had won. He’d done what Joey Ramone and Tom Verlaine never could -- stay weird and thrive. All of which makes his final solo album, “Nexterday,” hard to explain.

Lyle Lovett “Release Me”

Has there ever been someone so completely reliable as Lyle Lovett who looked so completely dodgy as Lyle Lovett? One of his eyebrows is perpetually raised while the other sits still. His mouth turns down in one corner while the other side purses. When he smiles, it looks like he’s in pain. And don’t even get me started with the hair. On the most superficial level, he does not look like a guy you can trust. And yet, by the 1990s, it was settled fact: Lyle Lovett is completely trustworthy. See the piles of four star reviews. The six straight Gold (not Platinum, because that would be too showy) albums. The four Grammy wins. And the fact that, in 2012, when he was making his “contractual obligation album” — the thing that is supposed to be resentful and perfunctory — he was still impossibly mannered and listenable. Turns out that Lyle Lovett is the exact opposite of dodgy.

John Fogerty “Revival”

Truth matters. Of course. But on the other hand — and especially in the curious case of John Fogerty — who the hell knows? Was he the Mark Twain of his generation or the Atticus Finch or was he just the guy who connected the musical dots between Ricky Nelson, Little Richard and Neil Young? How did the man who was once our answer to Paul and John just one day just disappear? As spectacular as Fogerty’s early run with Creedence was, everything that followed seemed like an unsorted mess. Seriously, what happened? Was he impossible to deal with. Did his muse dry up? Why was he always in court? Who was the hero and who was the villain? Time resolved some things. Lawsuits were settled. Contracts expired. People died. And, of course, John Fogerty had his beloved, if still perplexing, second act.

Steve Winwood “Roll With It”

In the second half of the 1980s, while we were happy to have luxury sedans in our garages and gas at the pump, there was still a sense of longing. Was it for JFK? MLK? The counterculture? Whatever the cause, our collective ennui — even as the economy boomed and the Cold War thawed — was unmistakable. We knew it, but we couldn’t place it. And so, we had questions. Fortunately for us, Bono had answers. So did Phil Collins and Sting and Bruce and Neil and, surprisingly, Don Henley. Our beloved Amnesty rockers, celebrated in the pages of Rolling Stone, sang with purpose. All of them, except for Steve Winwood, who opted for New Wave, Blues Brothers fare and farming in The Cotswolds. While his esteemed peers were consumed with importance, the most talented member of the bunch quite literally told us to roll with it.

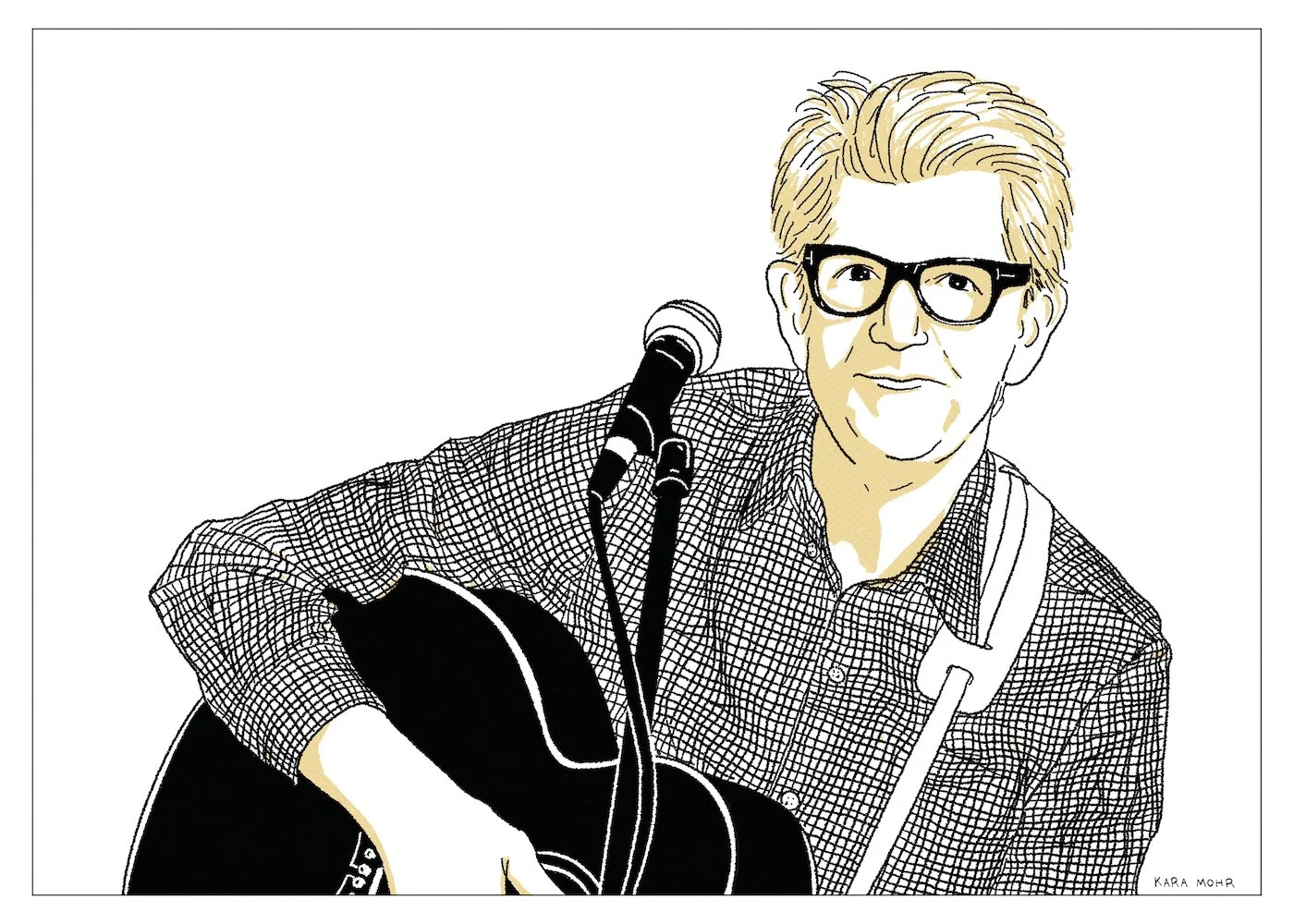

Nick Lowe “The Impossible Bird”

Once upon a time, Nick Lowe was the guy. He was New Wave’s beloved everyman — cool, but accessible. You might find him at the pub, you might find him on the Pop charts or you might find him in the studio with Elvis Costello. He married Carlene Carter and dated Lois Lane. To drop his name was to confirm your own hipness. By the early nineties, however, his time had come and gone. He was single, hitless, without a label and at the bottom of a pint glass. Amazingly, and with a little help from Kevin Costner and Whitney Houston, he dusted himself off and found a second act, functionally birthing his own genre of music in the process. Part Roots, part Country, part Rockabilly, and part Pop, the former mop-topped hipster became the white-haired songbird for discerning grown ups.

Darius Rucker “Learn to Live”

For over a decade, Hootie and the Blowfish were the butt of jokes — a 90s cliche nested between bad Gap sweaters and Sugar Ray. The probability of the backlash, however, was only surpassed by the improbability of Darius Rucker’s reemergence in Nashville in 2008. While his reign as the most successful Black musician in Country music now appears obvious, it was once, briefly, the object of cynical eyebrow raises. Taken together -- the backlash and the genre hop -- Rucker’s career resembles that of the Bee Gees and Ray Charles. He’s not the writer that Barry Gibb was and he’s not a sliver of Ray. But, also, he’s not Shania Twain or Mark McGrath or Rob Thomas. And he’s definitely not Hootie. He’s Darius Rucker, Country Music Star.

Bryan Adams “Shine a Light”

Almost forty years after he burst onto our radios, with a voice that humbled Rod Stewart and a style that translated Johnny Cougar into Canadian, Bryan Adams was still going strong. Arenas full of fans were shouting along to “Summer of 69” and crying along to “(All I Ever Do) I Do it For You.” He was closing in on sixty. He’d already sold a hundred million albums and topped every chart in the world. But, he still sounded exactly like himself, which is to say both like nobody else and like a hundred other guys. Naturally he looked older — more refined. His hair was richly coiffed and he’d swapped his leather jacket for a designer blazer. He’d even built a second career as a photographer — his pictures hung on gallery walls. There were only two things left for him to do: make new music with Ed Sheeran and prove to the world that “uncomplicated” is the opposite of an insult.

Duncan Sheik “Legerdemain”

In the mid-90s, after the crater of Alt Rock, a softer, lighter second wave followed, delivering Bubble-Grunge to Middle America. Though nominally inspired by their predecessors, Goo Goo Dolls and Matchbox 20 steered closer to the middle of the road than to its edges. It was during this flaccid period that Duncan Sheik appeared on the scene — similarly strummy, but better educated and mopier. His fans were certain that a nascent Nick Drake (or at least a Grammy) lurked inside Sheik. However, booze and pity partying ensured otherwise. That was, until 2006, when he wrote the music for “Spring Awakening,” an unexpected Broadway hit. It was not “Pink Moon,” but it was a narrative change. Nearly ten tears later, in middle-age, Duncan Sheik checked into rehab, got himself a blog and — against all odds — made the excellent record his college buddies had always hoped for.

Joe Jackson “Fast Forward”

You think you know a guy. He’s a jazzy New Wave Pop star. A classically trained pianist. A peer of Elvis Costello, who made it, and Graham Parker, who almost made it. As a young man, he made a couple of hit records that have held up. And then, in the mid-80s, he took the other road. For two decades, he scored films, paid tribute to his heroes and composed music for grad students. When he returned, many years later, he appeared startlingly different — all black clothes and a powder white face and hair. In middle age, Joe Jackson’s passion was still genre-defying music, but also, and maybe more so, libertarianism.

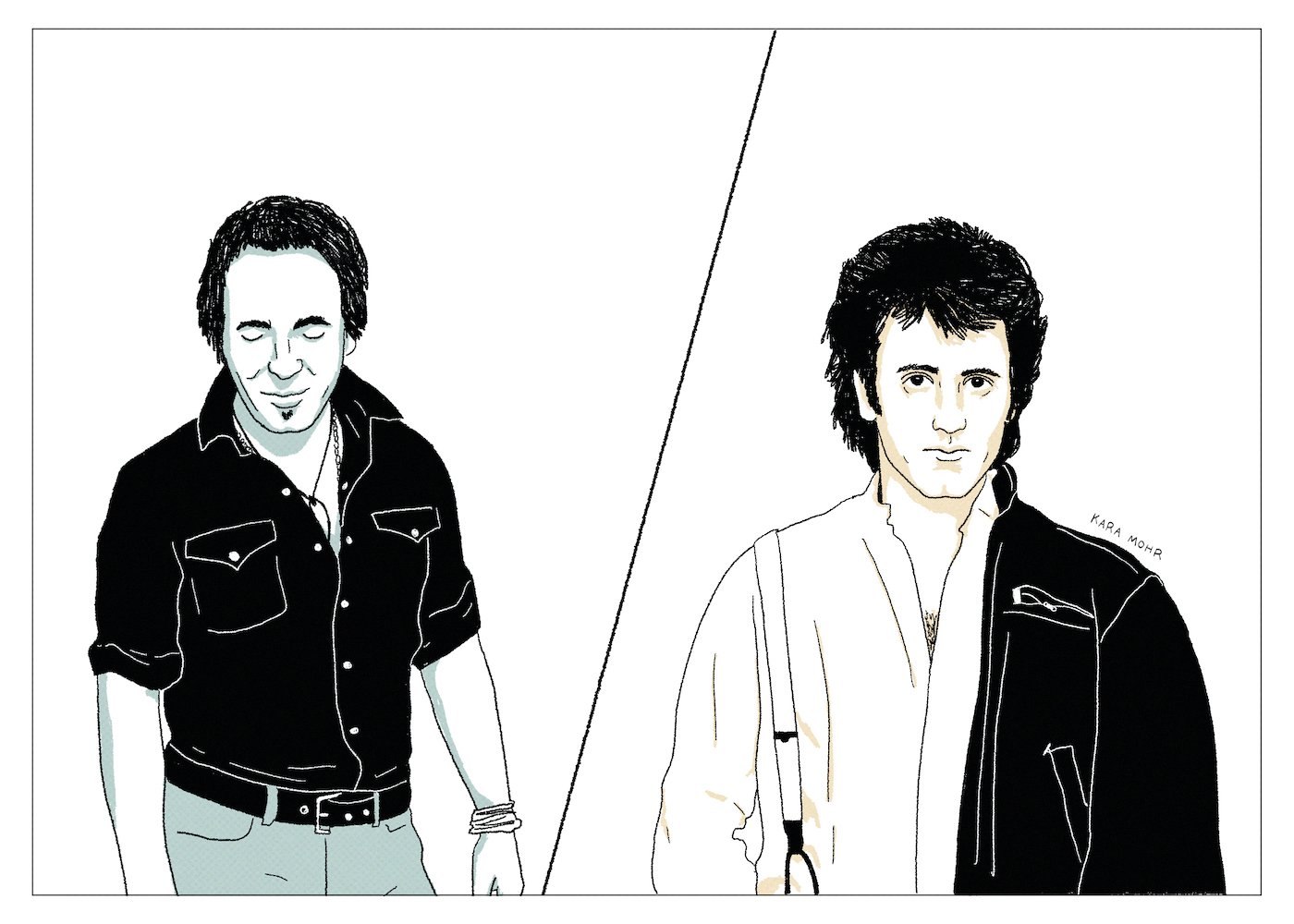

“Far From Over” (Frank Stallone) vs “All I’m Think’ About” (Bruce Springsteen)

In the early 70s, a million to one shot from the swamps of Jersey emerged as the “next Dylan.” Around that same time, less than a hundred miles away, a lesser known songwriter was fiddling with a keyboard, dreaming of the day that his older brother would include his music in the ultimate underdog movie. These two long shots, so near to each other but so completely divergent, demanded comparison. We pitted the nasal falsetto of Bruce Springsteen’s “All I’m Think’ About” from 2005 against Frank Stallone’s epic, 1983 Jazzercise jingle “Far From Over.” Who wins — The Boss phoning it in past his prime or the critically derided brother of Rocky during his graciously brief prime?

Beck “Hyperspace”

Since we finally met Beck, the grown up man, on “Sea Change,” a lot has happened: He got married. He had two children. He got divorced. He released seven albums -- most of them appreciated, and a couple beloved. He stayed in California. He stayed thin and pretty and a little weird. To the casual observer, he barely aged. But, with each successive album, he impressed less. There were no more “Odelays” or “Midnight Vultures.” In fact, to some fans and many critics, Beck became kind of boring. In 2002, I had firmly concluded that Beck could never be uninteresting. By 2019, however, I was less sure.

Luther Vandross “Luther Vandross”

Luther was the most polite Soul singer to have ever lived. We always knew that Al Green was grooving with euphemisms. We knew Smokey Robinson was being a little too cute. Even Michael Jackson tried to convince us that he was “Bad.” But Luther did none of those things. He was more interested in holding hands and gazing into our eyes over a candlelit dinner and a glass of Chablis. He built his career around silky vocals, a cherubic smile and good manners. But, in 2001, at the age of fifty, he lost half of his body weight, slapped expensive beats on his tracks and started to flirt like a grown up.

David Kilgour “The Far Now”

What’s it like to be a treasure, buried deep inside an island halfway around the world? What’s it like to be a semi-legend who cannot make a living doing what you are revered for? What’s it like to be a middle-aged artist who means so much to so few, but absolutely nothing to so many. Eventually, David Kilgour, the darling, Kiwi uncle of Indie Rock, gave up worrying about these sorts of things. “The Far Now” is his exhale — the sound of sunrise and sunset.

Waylon Jennings “A Man Called Hoss”

In 1987, off drugs, but stuck with a six pack a day habit, Waylon decided to make an “audio biography.” That lovable, but lightweight album was more like a Disney amusement park ride than the proper autobiography he would finally write ten years later. Taken together, though, they taught me what I needed to know about Waylon Jennings. That he wasn’t just an outlaw. Wasn’t just the guy who played bass for Buddy Holly. Wasn’t just a Highwayman. He was all those things. But, most of all, he was the guy with the perfect Country voice who screwed it all up, so that he could make it all right again.

Eddie Money “Ready Eddie”

If you really understand Long Island, you know that it isn’t Billy Joel country or Lou Reed country or Mariah Carey country or Bernie Madoff country. It’s Eddie Money country. Money was the one hit wonder who, from 1977 to 1988, just couldn’t stop making hits. He was the guy who sang “Two Tickets to Paradise.” He was Bruce Springsteen with two sides of ham and half as much talent. He was the “King of Generic Rock” who, in 1999, finally realized that “generic” also meant “easily replaceable.”

John Prine “Lost Dogs and Mixed Blessings”

We all knew he wasn’t going to be the “Next Dylan” (they never are). He wasn’t pretty enough to be Johnny Cougar. And he was too good to simply gut it out on Music Row. But John Prine never really went away. He just sort of stood in place waiting for us to circle back. That happened in 1991 when Petty, Bruce and friends helped celebrate the great comeback of an artist who hadn’t gone missing. Four years, a marriage and two kids later — Prine wondered: where do you go after you’ve just come back?

Neil Diamond “Heartlight”

Although it was not apparent at the time, Neil Diamond was on the verge of a slump as the 1980s approached. A sub-tectonic struggle was being waged between Neil Diamond, Contemporary Adult, and the emerging radio format known as “Adult Contemporary.” 1982, with the release of “Heartlight,” proved to be the year in which the movement swallowed its leader.