Journey “Revelation”

By 2006, Journey were on the ropes. The former heavyweight champs of Arena Rock had exhausted every possible alternative. Version 3.0 with Steve Perry broke down. Version 4.0 with Steve Augeri fizzled. Neal Schon didn’t need the money. And he probably didn’t need Journey, either. But we did. Those of us who grew up at skating rinks and on Atari — we could not stop believing. So, just like he’d done before, Schon found the best thing. On Youtube, he spotted a feathery haired, Steve Perry soundalike with a fairy tale backstory. And, just like that, Journey 5.0 released an affordably priced, three disc set through Walmart. One album of new material and two more of extraordinary karaoke. It was exactly what middle-aged, middle America needed.

Kevin Mitchell “All In”

Moments after The Clintons entered our lives, but right before PEDs consumed baseball, Kevin Mitchell was chasing immortality. By the All-Star Game, he was ahead of Babe Ruth’s home run pace. One night in April of 1989, he chased down a tailing Ozzie Smith line drive and caught it between the foul line and the wall — barehanded! Though I was not old enough to have seen Maris’ run at Ruth or Reggie’s run at Maris, I knew greatness when I saw it; even if it was sudden and unexpected and from a guy who was recently the fifteenth best player on the Mets. So, I responded in a way that felt beyond obvious to my eleven year old self: I emptied my non-existent bank account, forced my Dad to take me to the nearest baseball card convention and began to corner the market on Mitchell rookies. I was all in.

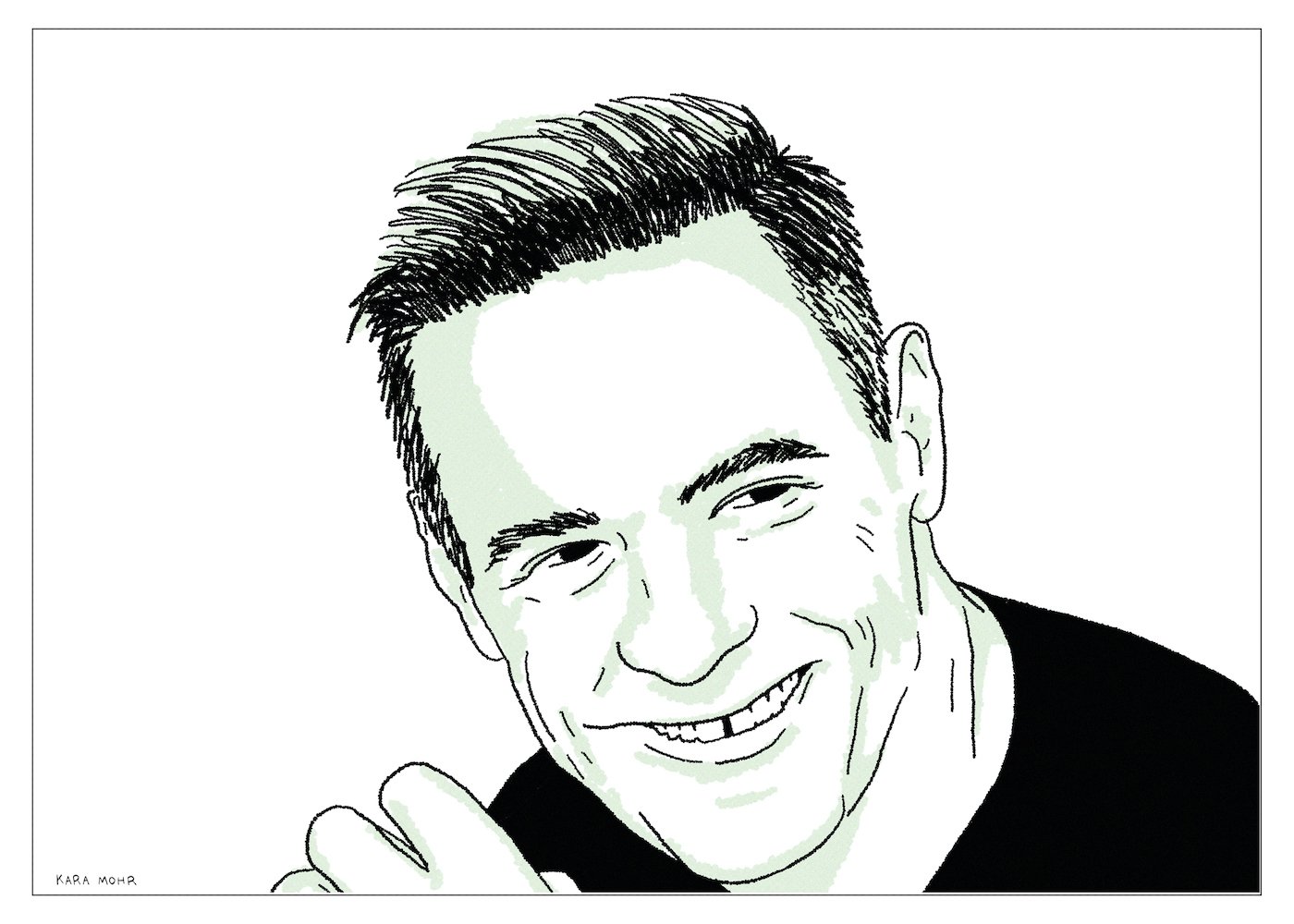

Bryan Adams “Shine a Light”

Almost forty years after he burst onto our radios, with a voice that humbled Rod Stewart and a style that translated Johnny Cougar into Canadian, Bryan Adams was still going strong. Arenas full of fans were shouting along to “Summer of 69” and crying along to “(All I Ever Do) I Do it For You.” He was closing in on sixty. He’d already sold a hundred million albums and topped every chart in the world. But, he still sounded exactly like himself, which is to say both like nobody else and like a hundred other guys. Naturally he looked older — more refined. His hair was richly coiffed and he’d swapped his leather jacket for a designer blazer. He’d even built a second career as a photographer — his pictures hung on gallery walls. There were only two things left for him to do: make new music with Ed Sheeran and prove to the world that “uncomplicated” is the opposite of an insult.

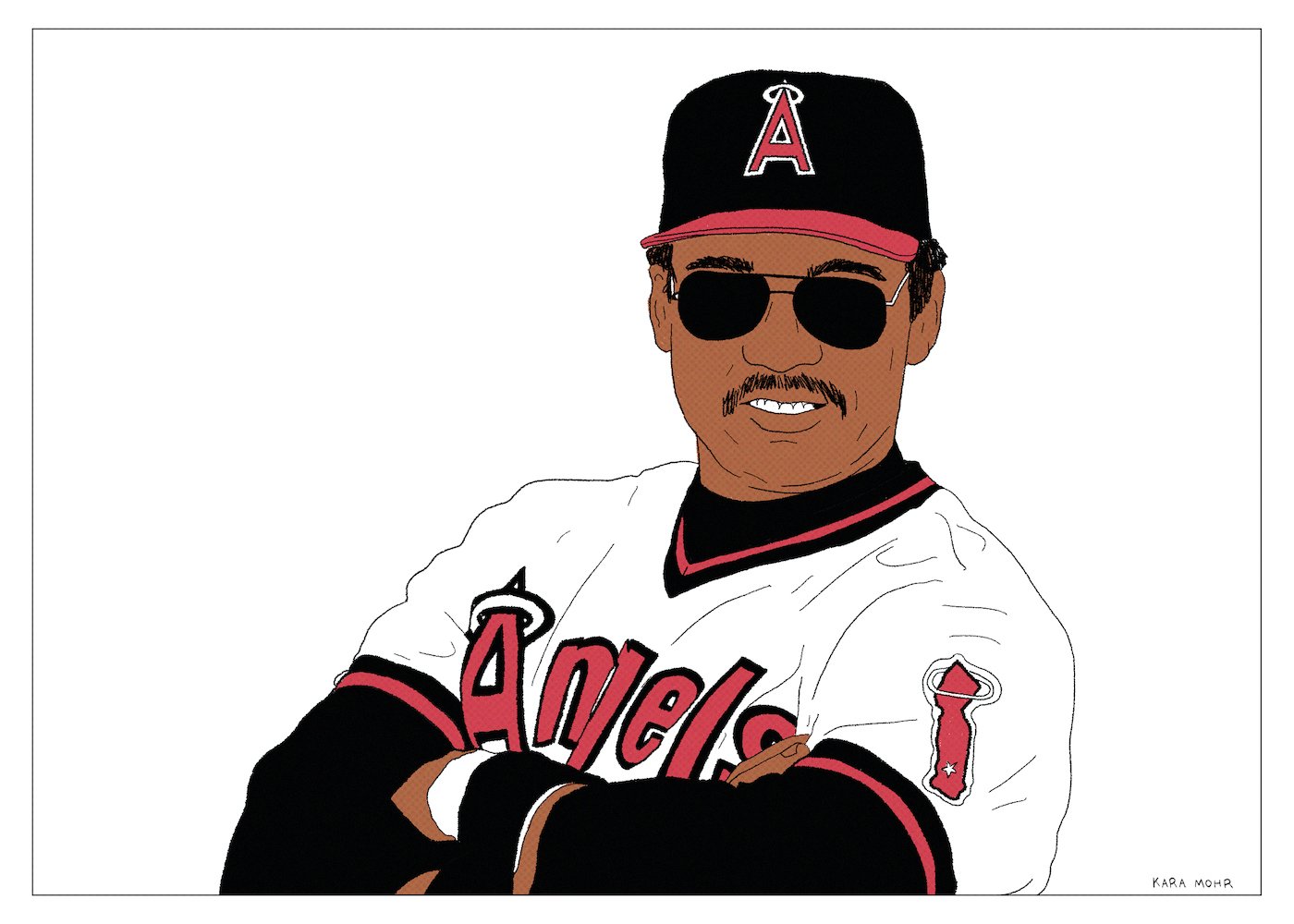

Reggie Jackson “Old Reggie”

In 1988, Reggie Jackson co-starred in “The Naked Gun,” where he attempted to assassinate Queen Elizabeth, only to be foiled by Enrico Palazzo. For younger generations, it is that Reggie — older, sillier, wearing prescription sunglasses — who they remember. But, not me. I was too young to remember Reggie, the young Oakland phenom. And I barely recall the magic of 1977. My Reggie was the superstar on a candy bar wrapper. At the plate, he appeared menacing and unpredictable — but still like a man. He wasn’t a bull, like Greg Luzinski, or a viking, like Gorman Thomas. Reggie just looked like a guy who wanted it way more. Who swung with more violence. Who tried harder. And who made it very easy to see how very hard it was to hit five hundred and sixty three home runs.

Duncan Sheik “Legerdemain”

In the mid-90s, after the crater of Alt Rock, a softer, lighter second wave followed, delivering Bubble-Grunge to Middle America. Though nominally inspired by their predecessors, Goo Goo Dolls and Matchbox 20 steered closer to the middle of the road than to its edges. It was during this flaccid period that Duncan Sheik appeared on the scene — similarly strummy, but better educated and mopier. His fans were certain that a nascent Nick Drake (or at least a Grammy) lurked inside Sheik. However, booze and pity partying ensured otherwise. That was, until 2006, when he wrote the music for “Spring Awakening,” an unexpected Broadway hit. It was not “Pink Moon,” but it was a narrative change. Nearly ten tears later, in middle-age, Duncan Sheik checked into rehab, got himself a blog and — against all odds — made the excellent record his college buddies had always hoped for.

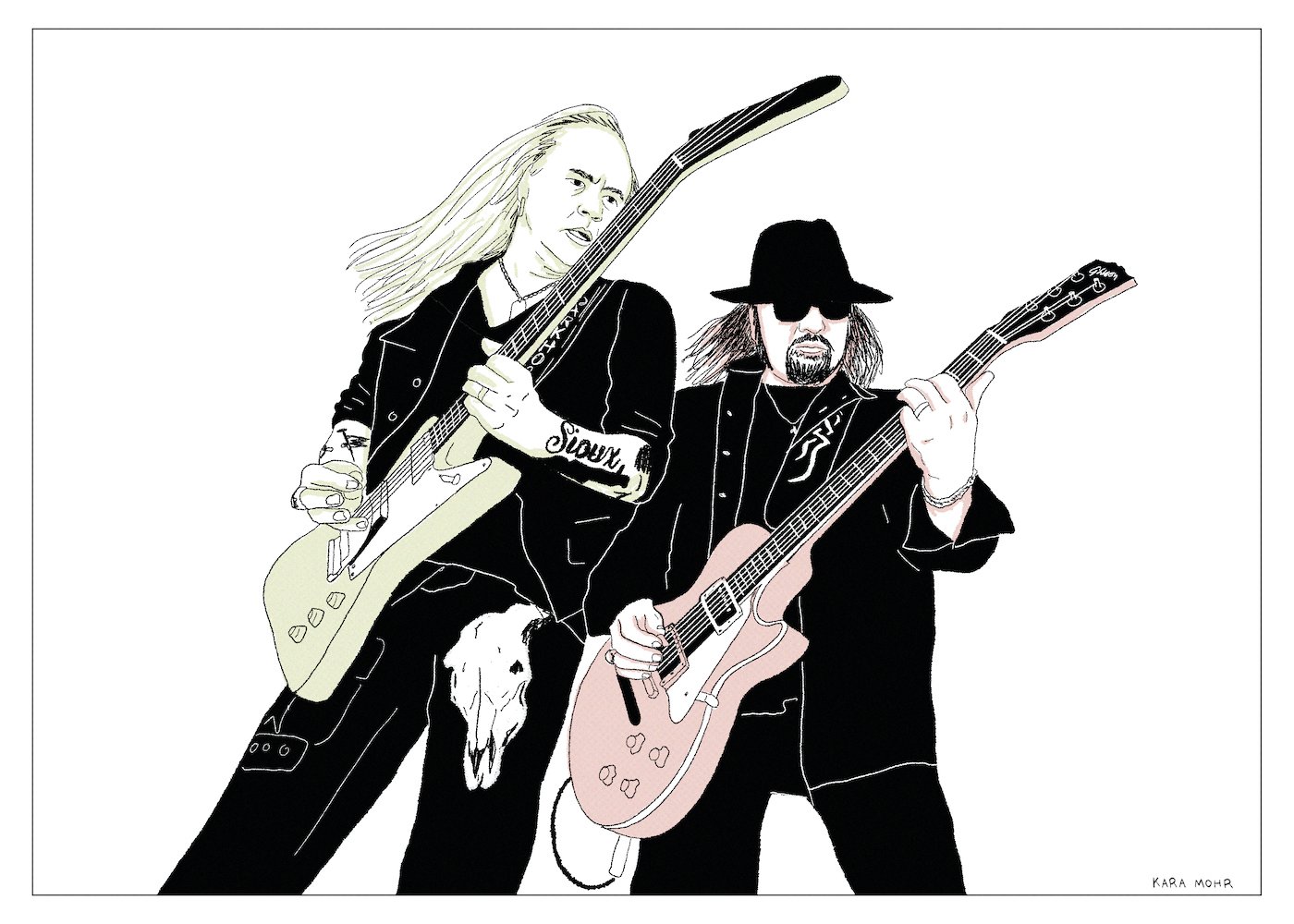

Lynyrd Skynyrd “God and Guns”

Some things in life are hard to talk about openly. For example, sex and money. When guys talk about sex or money, we tend to resort to cliches or jokes or hyperbole. On the other hand, it’s much easier for us to talk about music. In fact, we love to talk about music. Who are your bands? Are you a Stones guy? A Phish guy? A Blur guy? A Smiths guy? It’s organizing and safe. It’s the way we talk about our feelings, without really talking about our feelings. And it generally works for us. Except, of course, when it comes to Lynyrd Skynyrd. And especially when it comes to their 2009 album, “God & Guns,” which — to complicate matters — is absolutely not terrible. It may even be good — even when it’s being awful.

Joe Jackson “Fast Forward”

You think you know a guy. He’s a jazzy New Wave Pop star. A classically trained pianist. A peer of Elvis Costello, who made it, and Graham Parker, who almost made it. As a young man, he made a couple of hit records that have held up. And then, in the mid-80s, he took the other road. For two decades, he scored films, paid tribute to his heroes and composed music for grad students. When he returned, many years later, he appeared startlingly different — all black clothes and a powder white face and hair. In middle age, Joe Jackson’s passion was still genre-defying music, but also, and maybe more so, libertarianism.

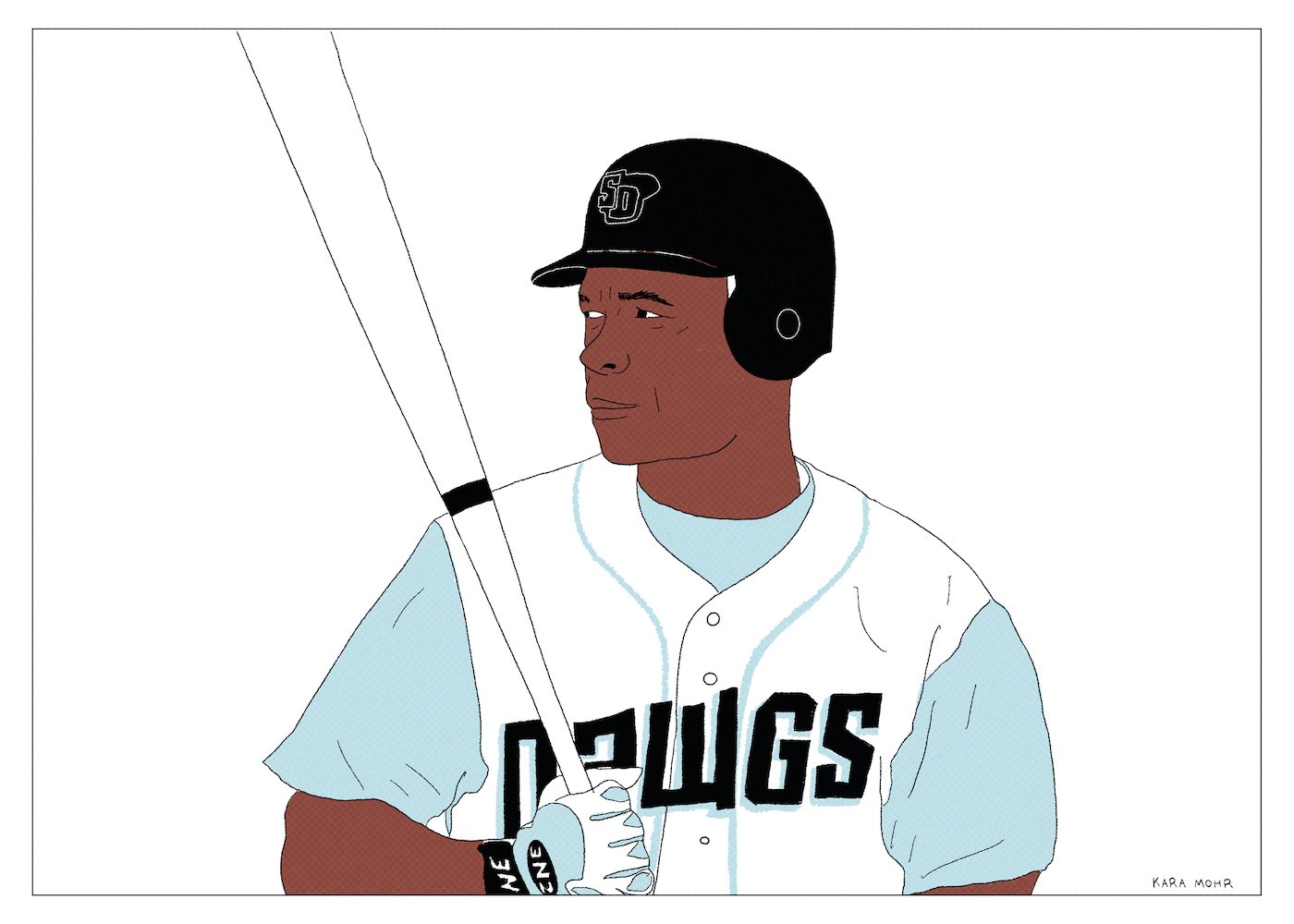

Rickey Henderson “The Greatest of All Time”

People (like me) lazily toss around adjectives like “incomparable” or “singular.” But there has never been a person so professionally atypical as Rickey Henderson. He made Steve Jobs and Henry Ford seem kind of average. He had more in common with Hermes or Spiderman than with Vince Coleman or Mookie Wilson. And, for twenty five seasons, he broke major league baseball. He wanted to play forever. He was certain that he could. But, in 2005, he was a San Diego Surf Dawg of the Golden Baseball League — where young men who will never make the Big Show went for a summer of fun and where former pros were put out to pasture.

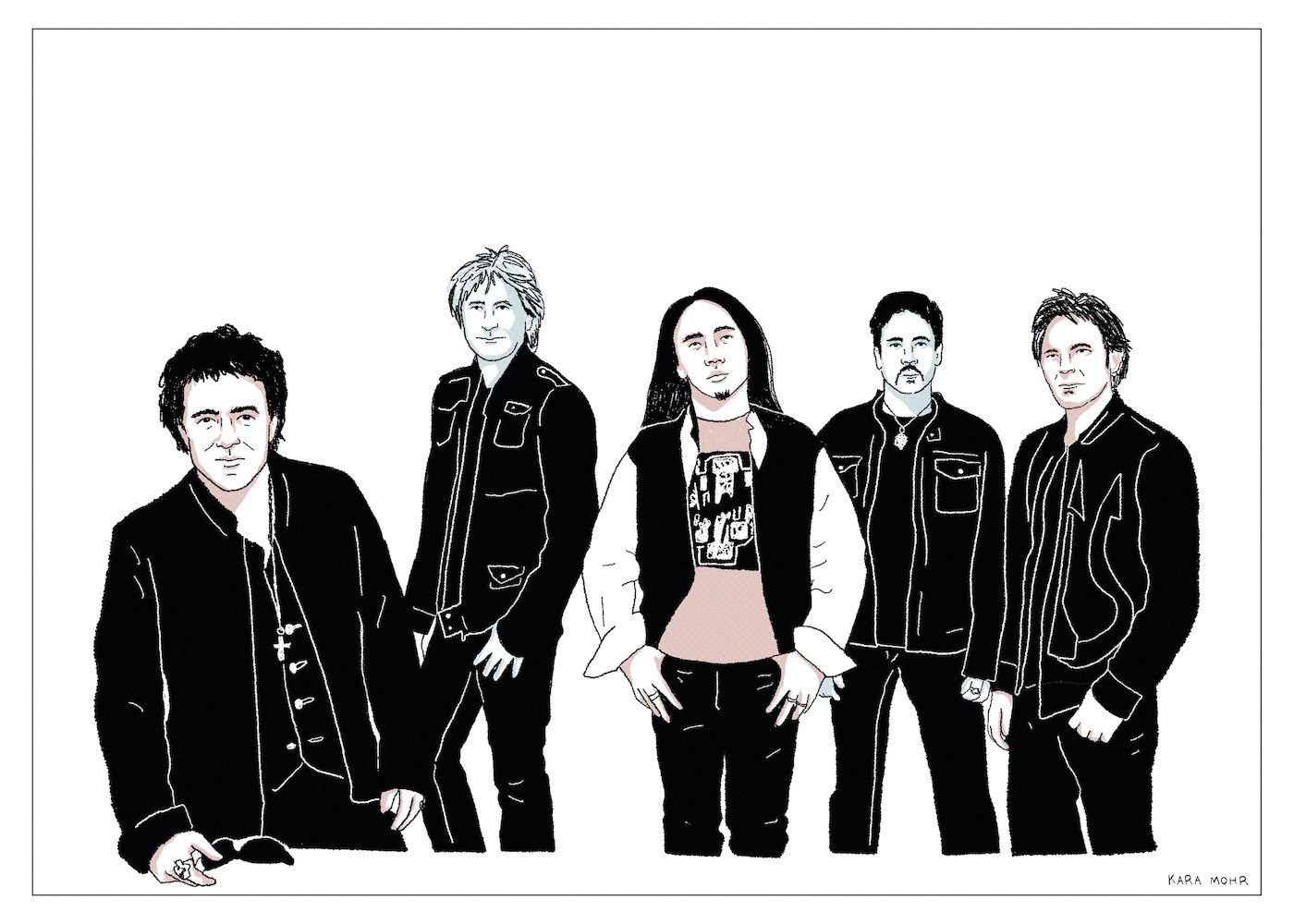

New Order “Waiting for the Sirens' Call”

Is it fun to be in a band? I used to think so. But, then, why does it seem so hard? Is it the anxiety of performance? The inevitable imposter syndrome? The monotony of touring and recording that The Kinks described so well in “Do It Again”? That plight -- the tragedy of fun -- is part of what defines and unites Goths, I suppose. It’s also probably the thesis of Post-Punk’s greatest band: New Order. For many years, the band that was born out of death hunted for fun in every corner of every club in the world. That was, until 1993, when drink and drugs and feelings got in the way. After a trial separation, they reunited, and embarked on a well deserved honeymoon. The fun, however, was short lived. By 2005, when they released the “Waiting for the Sirens’ Call,” divorce was in the air.

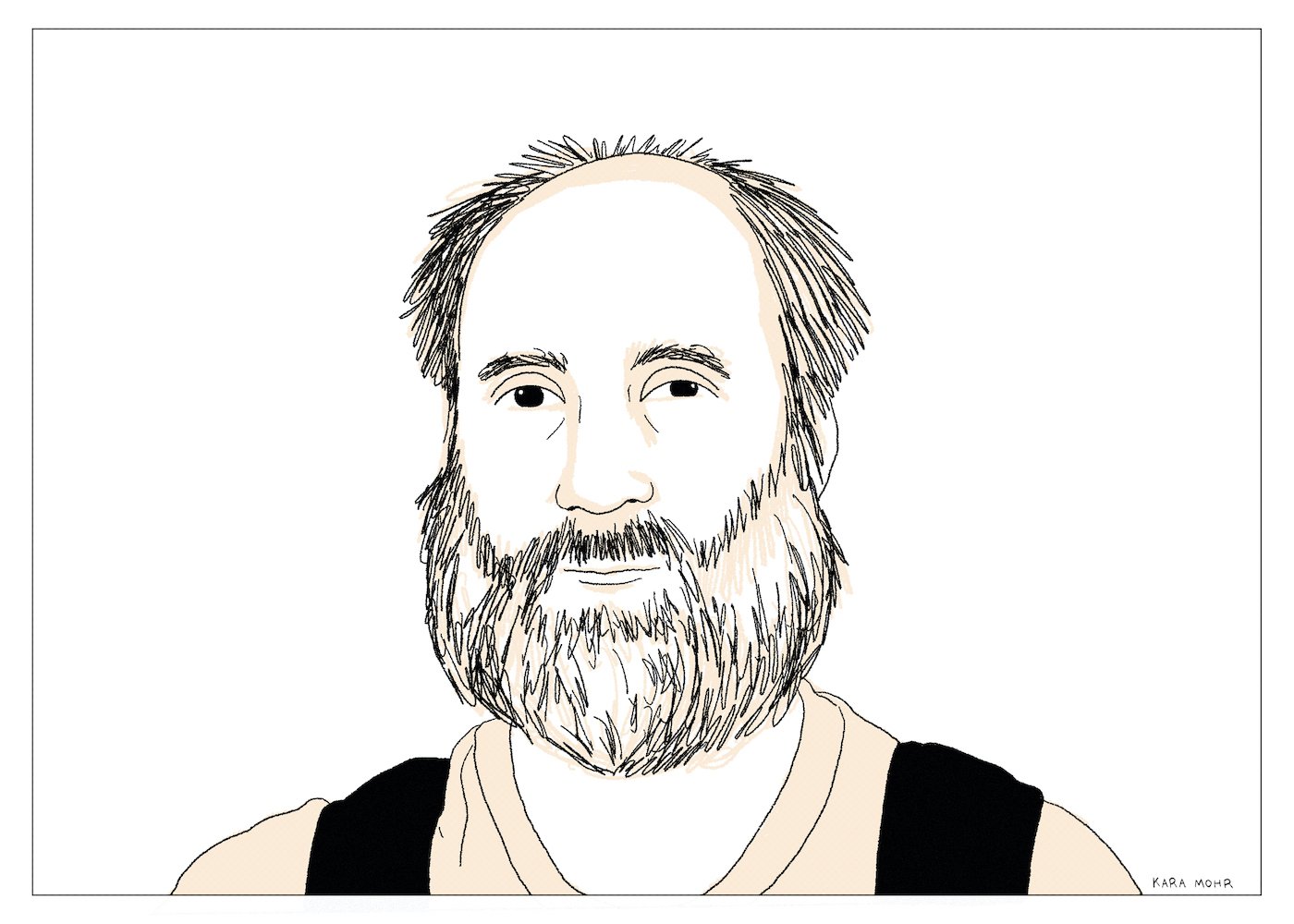

Built to Spill “Untethered Moon”

If I had to design an Indie Rocker -- for a movie character or a book proposal, or whatever -- I’d start with a guy from the Midwest or the Pacific Northwest. He’d be above average height and lanky, but in no way muscular. Maybe he played some baseball in high school, but sports weren’t that important to him. He drinks beer and smokes weed but doesn’t think much about either. He’s introverted, but also has plenty of friends. He’s dreamy -- not in the Jake from “Sixteen Candles” way, but in the always kind of thinking of something else way. He can figure things out. He built his own computer. He can hang drywall. He apparently has a band that nobody has ever heard but that you assume is pretty good. And, though he’s only twenty-something years old, he looks like he could be forty. He’s even got the beard to prove it. That’s the guy — the archetype. His name is Doug Martsch.

Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker “Keystone Kids”

Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker played nearly two thousand major league games together, turning over a thousand double plays between shortstop and second base. Trammell is in the Hall of Fame and Whitaker — based both on the data and Trammell’s impassioned case — should probably be there as well. They bunked together in the Minors, arrived to a suffering franchise in 1978 and, eventually, delivered the Tigers a World Series title in 1984. They are each other’s indisputable, number one fans. Forty years after they first played catch, the Keystone Kids have come to signify that elusive, romantic thing that men of a certain age rarely discuss but constantly long for: friendship.

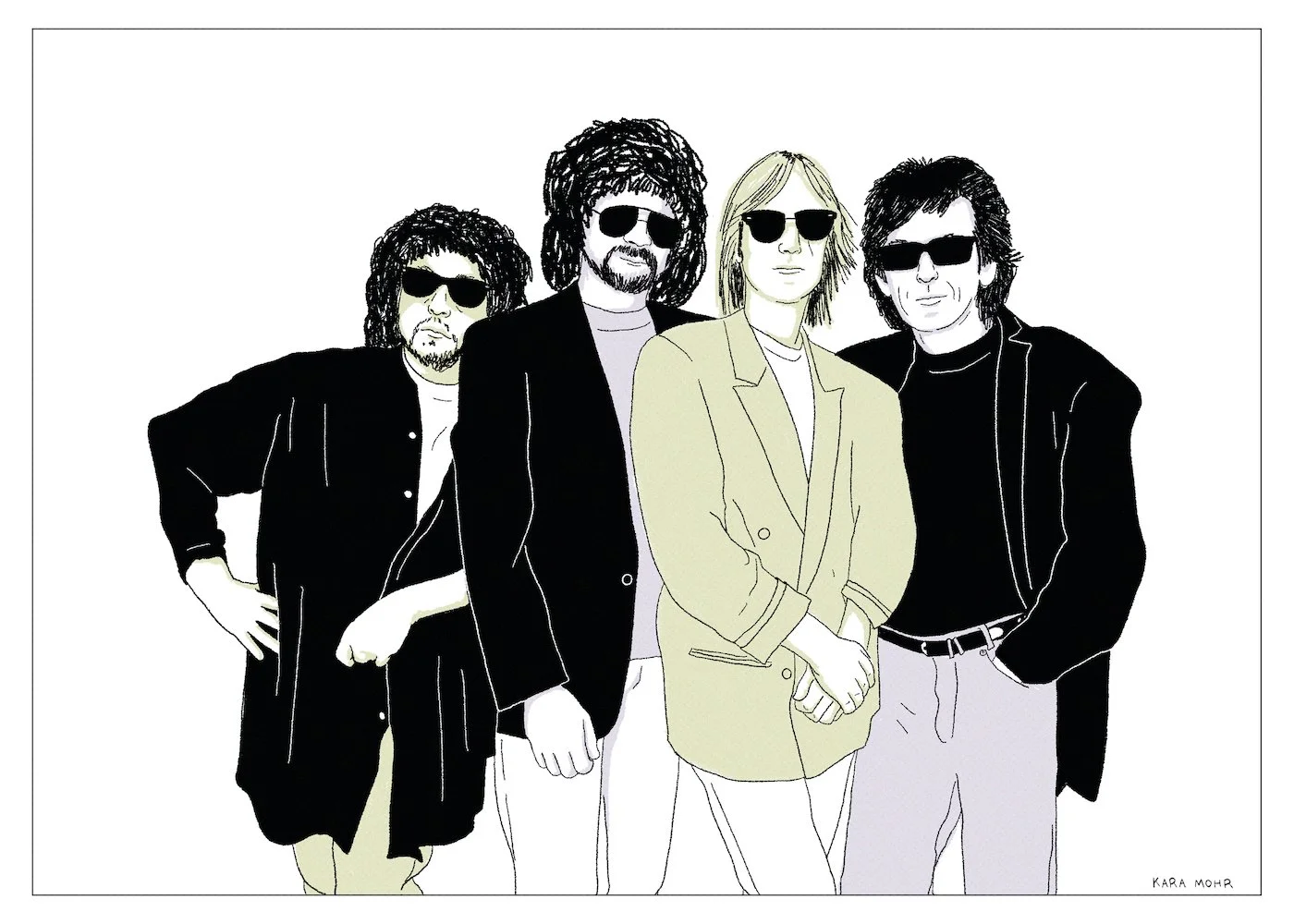

Traveling Wilburys “Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3”

The Traveling Wilburys were a “Supergroup” in name only. In reality, they were just a casual hang among middle-aged friends and admirers, who also happened to be Rock royalty. In 1988, they looked like half of an over forty, softball team from the Hollywood Hills — bad hair, extra paunch and beers after the game. The Wilburys’ debut is appropriately remembered for its easy going harmonies, for a couple of endearing hits and, sadly, for Roy Orbison’s passing. Many years later, it survives as a celebration (and commercialization) of “Past Prime.” History has mostly forgotten, however, that there was a follow-up album, complete with a bad “dad joke” for a title.

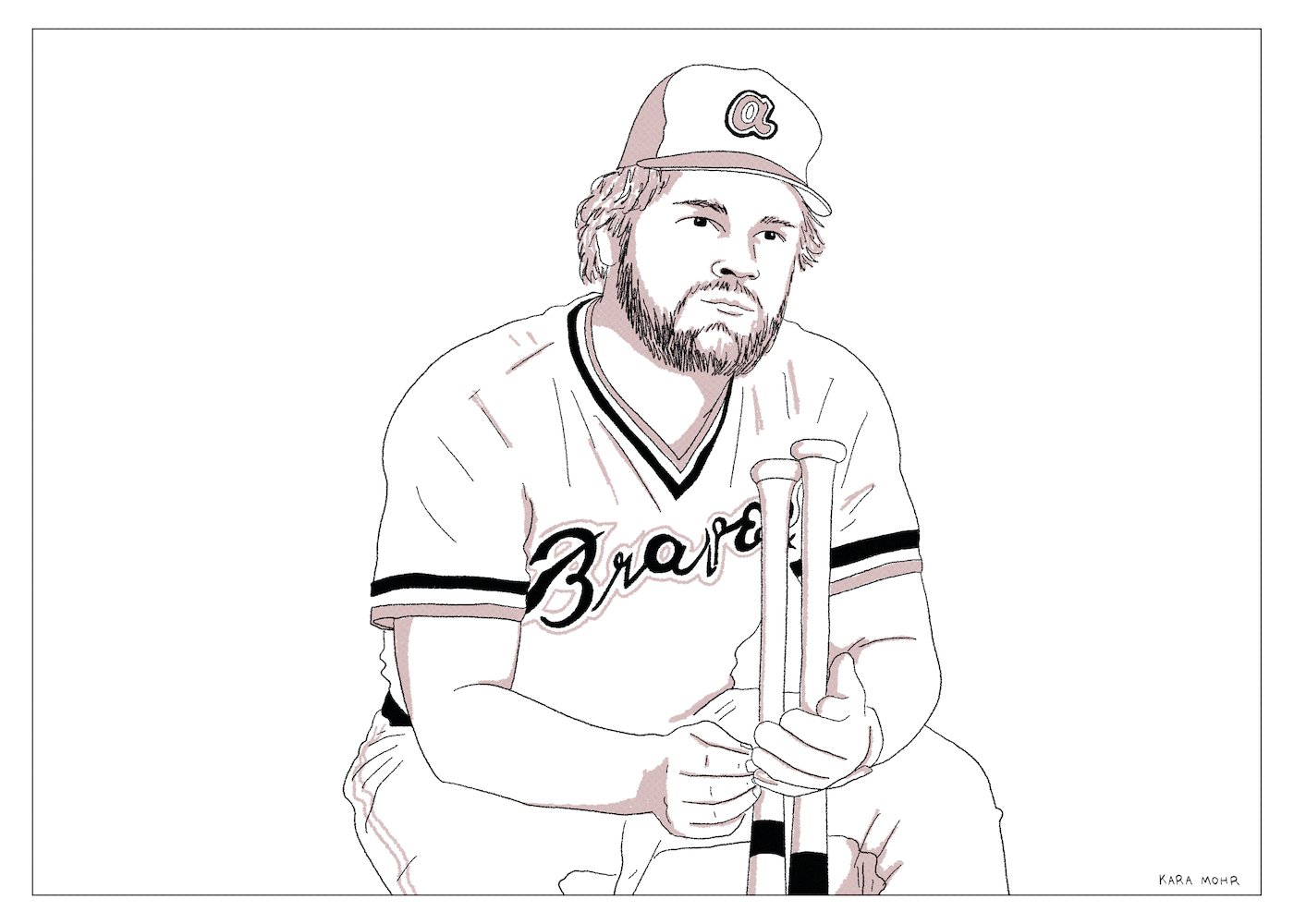

Bob Horner “Mr. Ho Mah”

Bob Horner never had career angst. He was born to use his hands and arms to strike objects with tremendous force. I suppose he could have been a great boxer, though that risks personal injury. Had he been born abroad, maybe he would be known today as the greatest cricket player of his generation. I guess he could have been the MVP of a building demolition outfit. Those were all possibilities. But when you’re born in Kansas in the late 1950s, and you look like the love child of Babe Ruth and Kenny Powers, there’s really only one job for you. It was unthinkable that he would do anything else with his life other than hit home runs and make terrible hair decisions.

Golden Earring “Keeper of the Flame”

Rock and Roll is littered with one hit wonders and spectacular flame outs. But Golden Earring were neither of those things. They had two, massive hit singles, both of which have oddly endured as canon. Decades after their prime, they were still superstars at home, in The Benelux, where their faces adorned postage stamps. But, as far as I knew, they had disappeared around 1983, soon after “Twilight Zone,” the four minute MTV mystery that altered my young life. What happened? Where had they gone? It all had a whiff of semi-Nordic true crime. Information was scant, especially in The U.S., where Golden Earring were the coldest of cold case files.

“Far From Over” (Frank Stallone) vs “All I’m Think’ About” (Bruce Springsteen)

In the early 70s, a million to one shot from the swamps of Jersey emerged as the “next Dylan.” Around that same time, less than a hundred miles away, a lesser known songwriter was fiddling with a keyboard, dreaming of the day that his older brother would include his music in the ultimate underdog movie. These two long shots, so near to each other but so completely divergent, demanded comparison. We pitted the nasal falsetto of Bruce Springsteen’s “All I’m Think’ About” from 2005 against Frank Stallone’s epic, 1983 Jazzercise jingle “Far From Over.” Who wins — The Boss phoning it in past his prime or the critically derided brother of Rocky during his graciously brief prime?

Jane’s Addiction “The Great Escape Artist”

By 2011, hell had frozen over enough that we began to expect the return of every legendary band. The Pixies, The Replacements, My Bloody Valentine, Pavement. The list was practically endless. It was simply too costly for those bands not to reunite. So, news of another album from middle aged Jane’s Addiction was kind of ho hum. For many, it was a curiosity, at best. At the core of this presumption was the belief that the great, unsustainable version of Jane’s had died in 1991. That they would return made only commercial sense. That they could recapture any semblance of their original brilliance made practically zero sense.

Air Supply “The Vanishing Race”

In retrospect, Air Supply seems unfathomable. Graham Russell looked like an overgrown Jeff Daniels with feathered hair. Russell Hitchcock was tiny, with a massive perm. Together, they looked like a Saturday Night Live sketch for a Hallmark ad about roller-skating buddies who loved cats. They were the naked, bawling men of Soft Pop who sang songs for exhausted, dejected, lovelorn ears. But, between 1980 to 1983, they scored eight consecutive top five hits, a feat only matched previously by The Beatles. By 1986, they were gone, off to redesign their Quaalude Rock for middle age and to celebrate their second career in the Philippines.

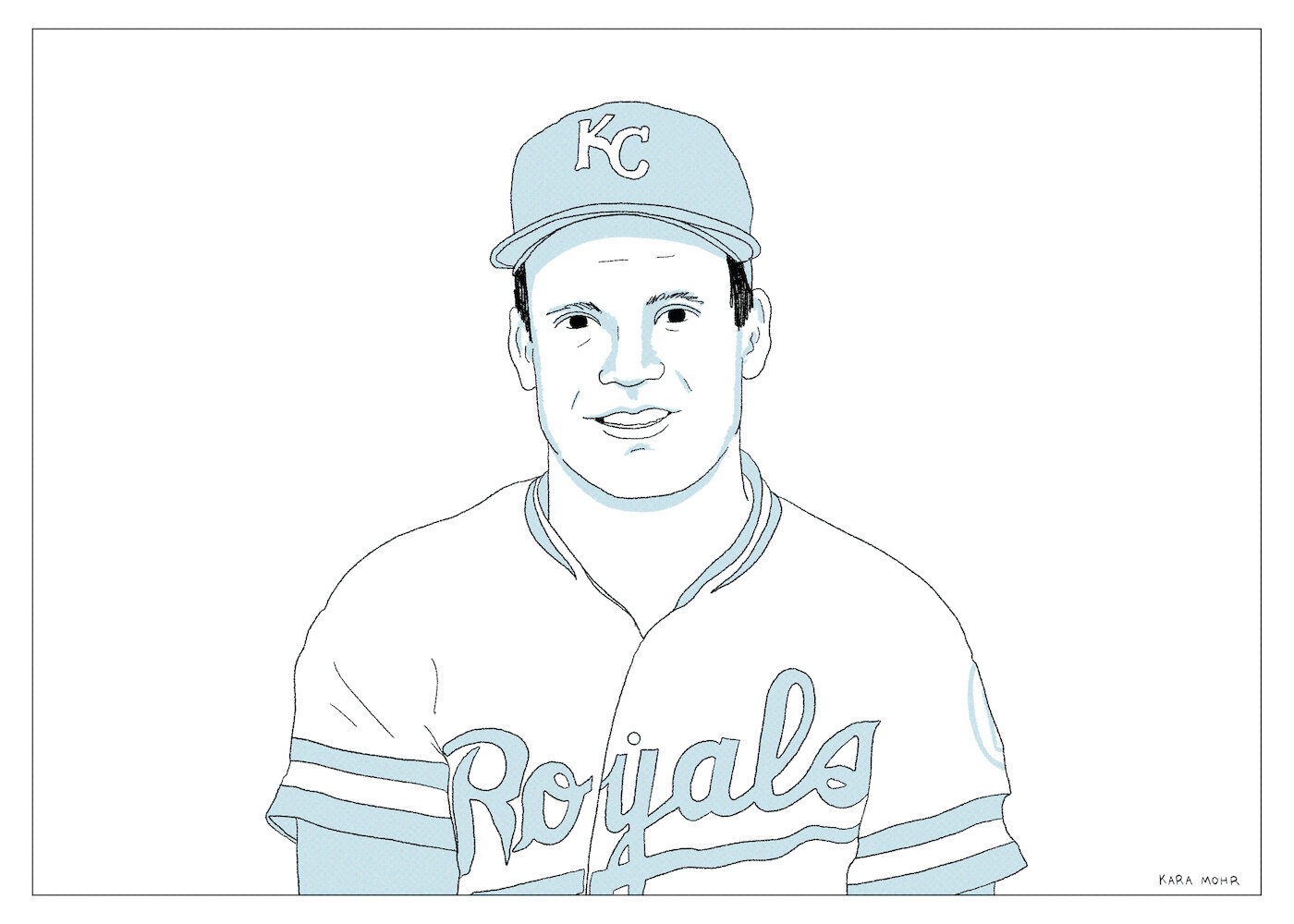

George Brett “The Bellagio Story”

At spring training in 2006, the greatest player in Kansas City Royals history told two minor league journeymen about the time he pooped his pants at the Bellagio, underneath the world’s largest installation of Dale Chihuly blown glass. The story is well known among Youtube diggers, Brett enthusiasts and, perhaps, baseball-inclined gastroenterologists. The mystery of this great story is not what plagues the Hall of Famer’s colon or how it relates to his Pine Tar Homer or whether it is even true, but rather why George Brett was so proudly insistent on the matter of his incontinence.

“Two Princes” (Spin Doctors) vs “Remedy” (The Band)

In 1993, The Spin Doctors gave MTV the winter hat plus hacky sack vibes the network sorely needed. Their unavoidable mega-hit, “Two Princes,” topped the charts and introduced Jam Band culture to the suburbs. Meanwhile, that same year, The Band reformed without frontman Robbie Robertson to make “Jericho.” One of the few originals from that album was “Remedy,” which charted nowhere and is remembered only by the most loyal of devotees. So, here’s the question: What’s better — an unforgettable song by a critically derided band in their prime or an unexceptional one from a beloved artist well past their prime?

Beck “Hyperspace”

Since we finally met Beck, the grown up man, on “Sea Change,” a lot has happened: He got married. He had two children. He got divorced. He released seven albums -- most of them appreciated, and a couple beloved. He stayed in California. He stayed thin and pretty and a little weird. To the casual observer, he barely aged. But, with each successive album, he impressed less. There were no more “Odelays” or “Midnight Vultures.” In fact, to some fans and many critics, Beck became kind of boring. In 2002, I had firmly concluded that Beck could never be uninteresting. By 2019, however, I was less sure.