Michael McDonald “Blink of an Eye”

There’s an aphorism that goes something like, “Brad Pitt is a character actor in a leading man’s body.” In music, there’s no direct equivalent for the Pitt aphorism. There are, of course, shy or mercurial singers — Bob Dylan and David Bowie fit that bill. But, solo artists, almost by definition, cannot be reluctant frontmen because they have no “back” to blend into. They are not part of a group — they are the show. The same applies to lead singers in bands, albeit for different reasons. There is really no such thing as a grudging frontman. A lead singer has to want it. Privately, they can be shy and awkward like Farrokh Bulsara, but when they hit the stage they have to be Freddie Mercury. That’s how it works. But, like all statutes, there are very rare exceptions. In the case of Rock and Roll frontmen, there is one indisputable outlier — a guy who sounds like Bob Seger and Darryl Hall at the same time. Who, once upon a time, looked like the love child of bearded, post-Beatles McCartney and a soul puppy. A guy whose voice is as rich as a yacht but who always preferred to be in the background, heard more than seen.

Blues Traveler “North Hollywood Shootout”

On so many levels, our aversion to Blues Traveler is ridiculous. Of all those Nineties Jam bands, why them? There were many lesser variations. Bands who couldn’t play with singers who couldn’t sing and jams that went nowhere. Blues Traveler was barely any of those things. They were a solid Roots Rock band with a mascot for a lead singer; far more exciting than their closest predecessor — Spin Doctors — and their more successful, distant cousin — Hootie and the Blowfish. If anything, their brief apex was a fluke — a product of commercial radio’s (and MTV’s) inability to separate Beck from Better than Ezra. For one strange moment in 1994, Modern Rock, Mainstream Rock, Pop and Adult Alternative formats all sounded oddly similar — jangly and towing a line between earnest and ironic. Basically, like the sound of Blues Traveler. On the other hand, reducing them to a bad haircut, does a grave injustice to the band. It also obscures the harmonica in the room — the dozens and dozens of harmonicas in the room.

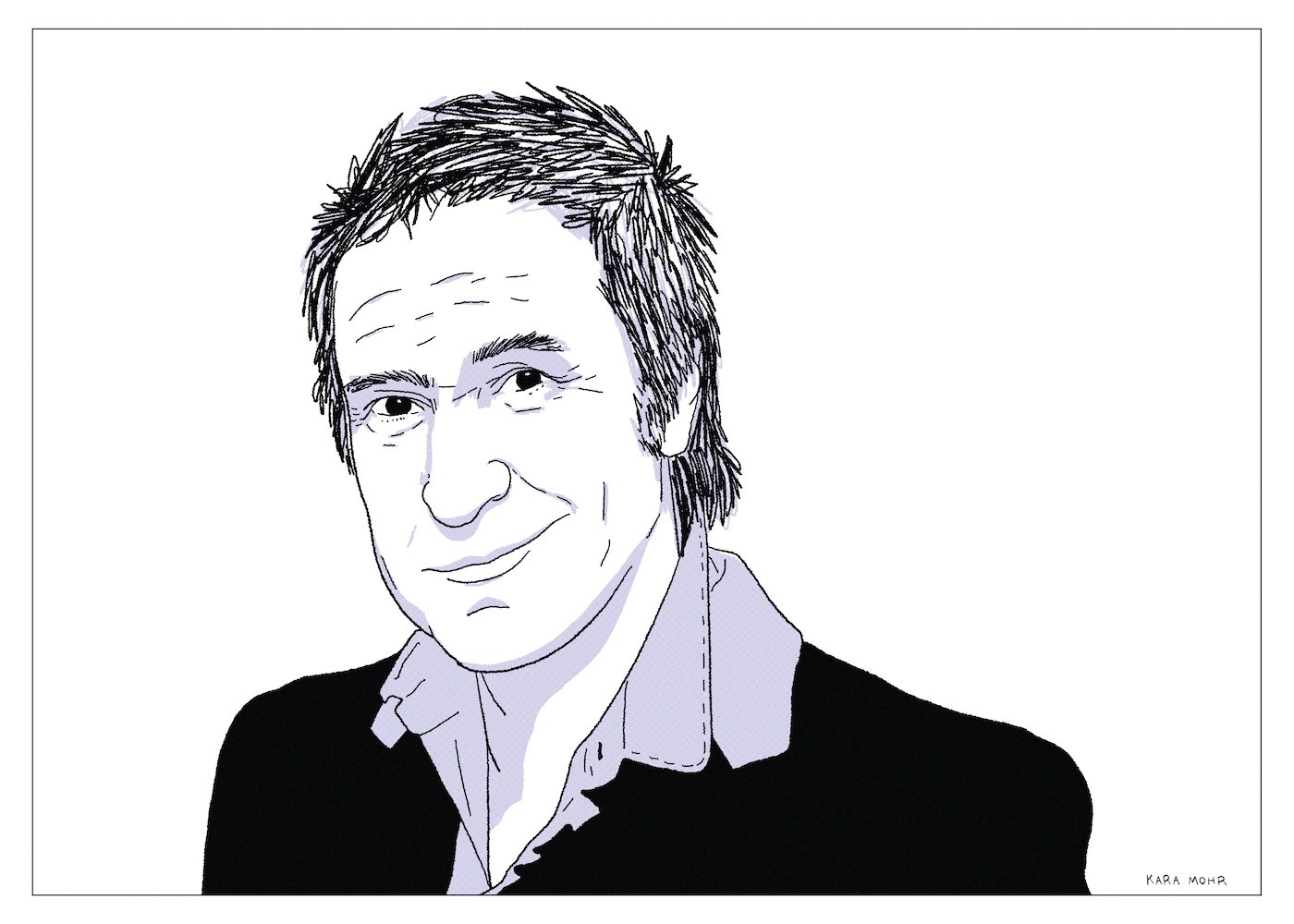

Ray Davies “Americana”

As a musical style, Americana suggests something in between “Roots Rock” and “Alternative Country.” Stylistically, it's a fertile if ultimately narrow genre. But, Ray Davies’ “Americana” is not Whiskeytown’s “Americana.” Davies’ is as expansive as it is deep. It considers both the United States of America and the land mass that predated the country — the massive mountain ranges and the canyons and rivers and the natives and the cowboys. The freedom and independence and capitalism and Jazz and Blues and Soul. The New York and Los Angeles and high hopes and dashed dreams. All of it. The man who wrote “A Well Respected Man,” “Waterloo Sunset” and “Village Green Preservation Society” — the singer-songwriter who satirized and romanticized English life was enraptured with America. England consumed his mind, but America held his heart.

Van Morrison “The Album Covers”

Before he became a craggy, portly Soul man in fedoras and suits, before he was a grumpy anti-lockdown militant, before the Skiffle record and the Facebook rant and a song so profoundly sad (“Pretending”) that it was somehow more depressed than his song about walking out on a friend with tuberculosis (“T.B. Sheets”), before the healing and the silence and the hymns, and before he stuffed himself into that stretchy leisure suit get up for “The Last Waltz,” George Ivan Morrison cared deeply about his album covers. But that was then. Today, Van survives as the artist whose album cover art most betrays the product contained within. His obsession with “tone” and “feel” is surpassed only by the depth of his disdain for the art that adorns his music.

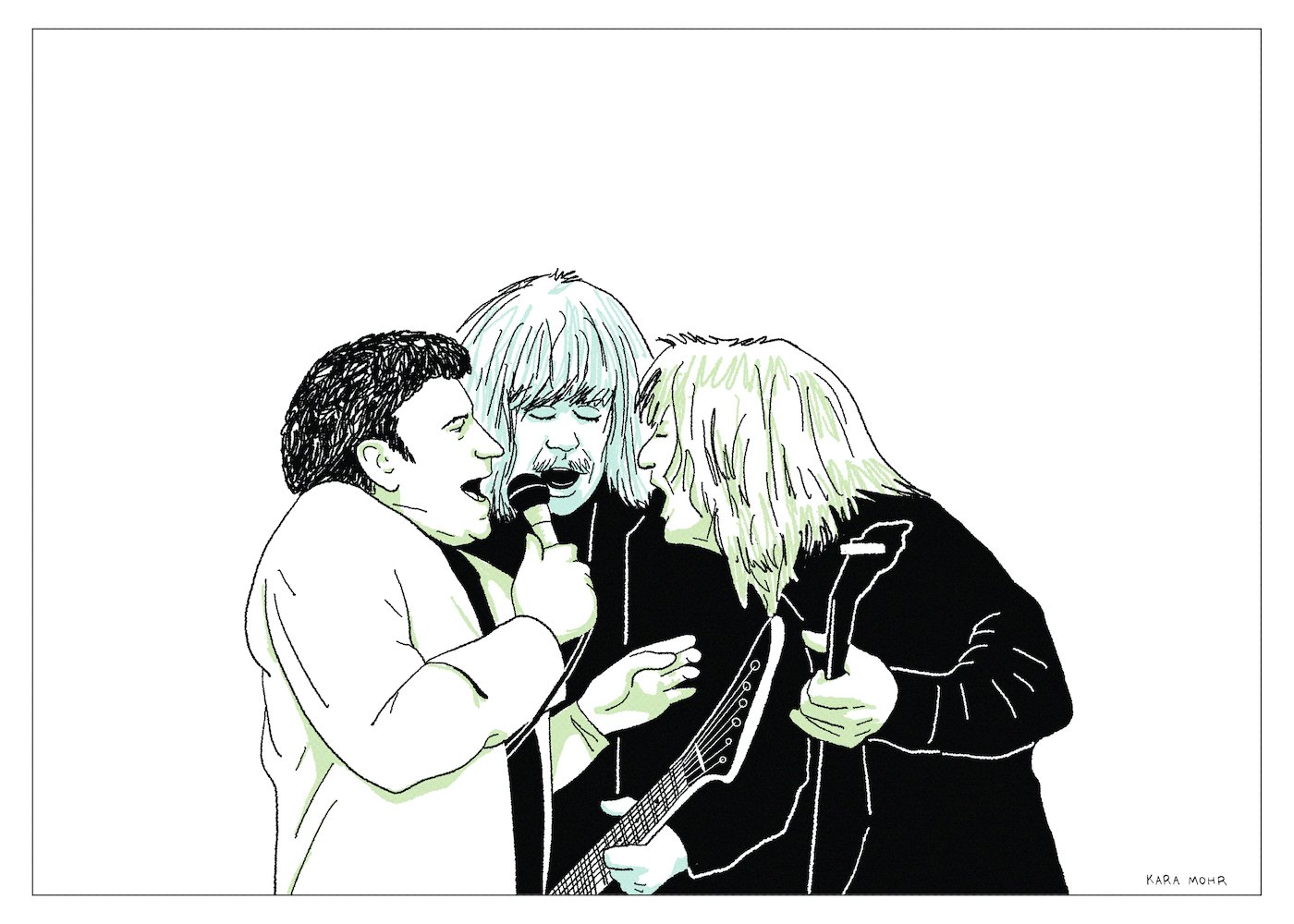

Styx “Brave New World”

Like Queen, with whom they’ve often been compared, Styx has always been the kind of band that swings for the fences. Most of the time they whiff — but in a charming “love the effort” sort of way. When they connected, however, as they did roughly one time per album between 1973 and 1982, they hit it out of the park. Way out of the park. During that run, DeYoung, Shaw, Young and the Panozzo brothers scored a half dozen top ten hits and five consecutive platinum-selling albums. And yet it always seemed to me that the band was a mistake — that we already had Queen and Journey. That DeYoung should be wowing audiences on Broadway (which he eventually did) and that Shaw should be fronting a Hair Metal band (which he also eventually did). By the end of the Nineties, seventeen years removed from the dystopian, sci-fi hit that broke the bank and the band, Styx were still swinging, but no longer connecting.

Squeeze “Cradle to the Grave”

Though early on they were compared to Lennon and McCartney, Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford were much closer to Elton John and Bernie Taupin. Tilbrook was a master tunesmith and Difford was an equally gifted wordsmith. For the most part, however, (and unlike Lennon/McCartney) they worked separately, fitting and refitting their own parts to the others’ material. Tilbrook, the more gregarious and intuitive one — he leaned towards the Beatles. Difford, more contained and cerebra, leaned towards Post-Punk. One man was blonde. The other brunette. They were childhood classmates, but, from the outset, and in spite of their shared interests, they were also a study in contrasts. During Squeeze’s first break-up, the two men actually made an album together, under their own names. After the second divorce, however, things got ugly. Jools Holland was gone, the hits dried up and Difford bottomed out. From the outside, it seemed certain that Squeeze was done. From the inside, it appeared even worse.

John Hiatt “Perfectly Good Guitar”

There’s a concept in child rearing — and I’m honestly not sure if it’s armchair psychology or actual science or what — called “perfectly adequate” parenting. Its premise is radically simple: that parents should be no more or no less than their child needs. One the one hand, it makes a lot of sense. On the other hand, nobody really wants to be “perfectly adequate.” Not in parenting. Not in life. Not in work. And, certainly, not in music. Pop music is defined by highs and lows. By mania and soul. The road in between is longer, and oftentimes much harder. It’s a workmanlike path — one that is rarely disruptive or revelatory, but is eventually, and amazingly, just right. Richard Thompson is always perfectly adequate. Sometimes more. Never any less. John Prine. Lyle Lovett. Nick Lowe. Always perfectly adequate. But of all the singers I can think of, the one who is most truly perfectly adequate — whose skill is evident, whose records are solid and whose faith and commitment is unwavering — is John Hiatt.

Tin Machine “Tin Machine II”

By the late Eighties, there were no fresh blood for David Bowie — the greatest vampire in Rock and Roll — to suck. The top Rock radio songs of 1988 included Henry Lee Summer’s “I Wish I Had a Girl” (what? who?), Bruce Hornsby and the Range’s “Valley Road” (rocks so light) and Tommy Conwell & The Young Rumblers’ “I’m Not Your Man” (not a typo, I checked). After two consecutive duds, Bowie was desperate for inspiration, but the pickings were slim. And so, he did what desperate people do. He found the nearest available guy and went all in. No research. No courtship. He just needed a guy with a beating heart, pumping blood and some capacity to make music. But mostly, he someone who could be a willing host to a brilliant parasite. Reeves Gabrels was that new host. And, in spite of his regal sounding name, he was truly just a guy — a guy from Staten Island, New York, who happened to be married to David Bowie’s tour publicist. One day, Gabrels was playing steel guitar in Rhode Island for a band called Rubber Rodeo. A year later, he was the cofounder of Tin Machine.

Warren Zevon “Sentimental Hygiene”

Following the unexpected success of “Excitable Boy” in 1978, Warren Zevon’s commercial prospects began to fade. “The Envoy,” from 1982, was predictably literate, frequently dark and occasionally brilliant. But, also, it flopped. Within a year of its release, Zevon was a black-out drunk divorcee, dropped from his record label and going nowhere fast. He licked his wounds, tried, failed, tried again, failed again and — eventually — succeeded in getting sober. It would be another five years before he released another album. In the interim, outside of his family, Jackson Browne, a bunch of L.A. session guys and a coterie of writers and critics, Zevon was more forgotten than he was missed. But then, in 1985, while Tom Cruise sashayed around the billiards table like a ninja pool hustler, Martin Scorsese dropped the needle on “Werewolves of London” and people suddenly started talking about Warren Zevon again.

Leon Russell “Anything Can Happen”

Having spent more than a decade building his reputation as the “guy to call” when you needed a guy, Leon Russell was suddenly more than just “a guy.” He became “the guy.” In 1970, after touring with Delaney and Bonnie and releasing a critically adored solo debut, he put on his top hat, dusted off his beard and assembled the greatest live band on the planet for Joe Cocker’s “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” tour. And though the experience nearly killed him (and his bandmates), it marked the beginning of the next phase of his storied career. Whereas during the 1960s, Russell was on the side or behind the scenes, in the 1970s, he was a frontman, gracing album covers, standing center stage, and sharing the limelight with everyone from George Harrison to Willie Nelson. For a natural introvert who was perhaps meant to be a bandleader more than a Pop star, it proved to be too much for him. Depleted and lost, the man who’d released over a dozen albums in the Seventies, eked out only two the following decade. By the Nineties, he was stuck somewhere between the “where are you now” and the “who’s that guy” files. Leon Russell lost his way and then began to fade out, until, one day, Bruce Hornsby came a calling.

Keith Rainere “Totally Innocent Prog Rock Genius”

According to Nancy Salzman, at some point just before scoring the world’s highest IQ and becoming one of the world’s three greatest problem solvers, Keith Rainere taught himself many musical instruments, including the piano, which he could allegedly play at a concert level. Of the many claims made by NXIVM, I found this one most confounding simply because it is the most disprovable. During the nine hours of “The Vow’s” first season, the only proof we get of Rainere’s musical gift is a brief, middling performance of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” — a piece generally taken on by younger students in the first few years of their studies. On the basis of this showing, it’s hard not to conclude the obvious: Keith Rainere is no Keith Emerson. So, why? Why did he make such a bold and obviously false claim? IQ tests can be forged. Problem solving is hard to measure. But musical aptitude is hard to fake. The answer to my question arrived in the late Spring of 2019. According to the New York Post, some time after mastering all of those instruments but presumably before breaking the IQ test, Keith Rainere got really into Prog Rock — specifically Yes and Genesis. Which explains everything.

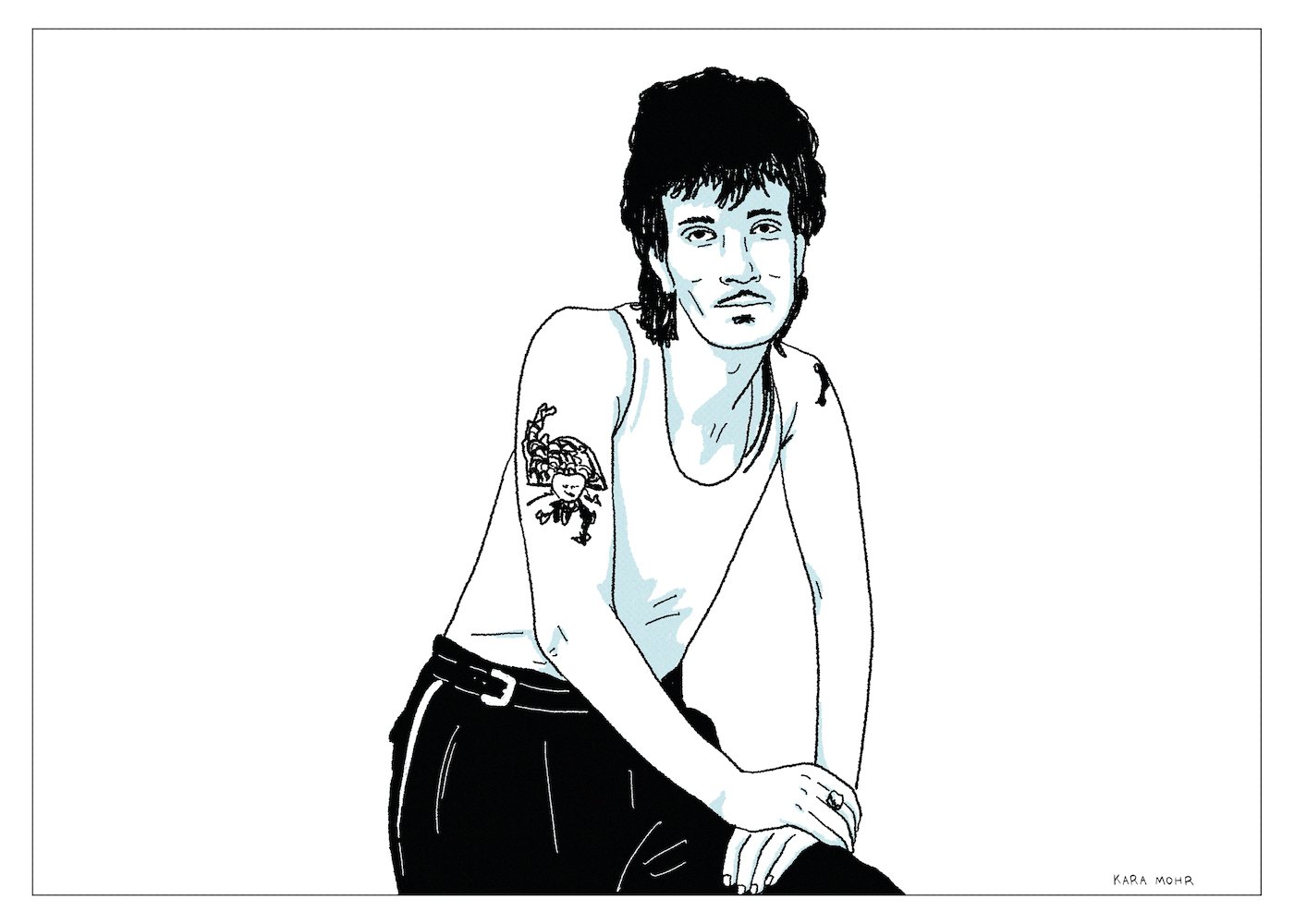

Willy DeVille “Backstreets of Desire”

When Dylan went from folkie hobo to poet in black turtleneck and shades, it seemed like affect. When Bowie went from Ziggy to Thin White Duke, it felt like an art project. And when Madonna went from Material Girl to S&M Barbarella, it came off like a marketing stunt. But Willy DeVille was the genuine article — a real life shapeshifter. The man born William Borsay Jr., from Stamford, Connecticut, would become a Spanish Harlem pimp, a Bowery gutter prince, a riverboat gambler, and a Navajo mystic. In 1992, somewhere between the Bayou and his eventual return to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, he briefly wound up in Los Angeles. And, in spite of crippling addiction and decades of commercial disappointments, Willy made one of the great, barely heard Roots Rock albums of the decade. “Backstreets of Desire” might read like something from Springsteen’s swamps of Jersey, but it sounds like the Los Angeles that made Los Lobos, Tom Waits and Warren Zevon.

Bon Jovi “This House Is Not for Sale”

Though they were no longer America’s Biggest Rock Band, Bon Jovi could still sell (many) millions of albums. But it was clear to anyone who was paying attention that things had changed. Jon cut his hair and took up acting. Richie married Heather Locklear. Over the course of three decades, they’d traded in grit for nostalgia. Their fearlessness was subsumed by trite optimism. And though they’d sustained their spot on the charts, they’d regressed from something iconic to something more generic. By 2015, they had to confront the existential risk that all Arena Rock bands some day face: the challenge of being both universal and distinct. Many great bands had fallen into that chasm before: Journey, Foreigner and REO Speedwagon to name a few. But, not Bon Jovi. In just a few years, and without Richie Sambora, they went beyond arenas. Beyond namelessness and facelessness. They became the Bud Light of Rock and Roll — the highly consumable, mostly bland complement to Fox Sunday football.

Alice Cooper “Trash”

The early 80s were not kind to Alice Cooper. Sober, but restless, he tried new gimmicks. He brought more snakes onstage. He tried his hand at New Wave. He traded booze for golf. But nothing seemed to work. By the mid-80s, while Hair Metal — a genre that he’d in part given birth to — was ascending, Alice Cooper was nothing more than a charming “has been.” But then, when it seemed that he was all past and no future, he caught a massive break. Desmond Child, a longtime fan and, more importantly, the super-producer of gargantuan, shout-along hits by KISS, Bon Jovi and Aerosmith, offered to help the forty year old, Shlock Rocker reclaim his throne. In order to succeed in the mission, Child had one requirements. He demanded that Cooper sing about the one thing that all teenagers are obsessed with but which the future GEICO spokesman had somehow avoided for his entire career: Sex.

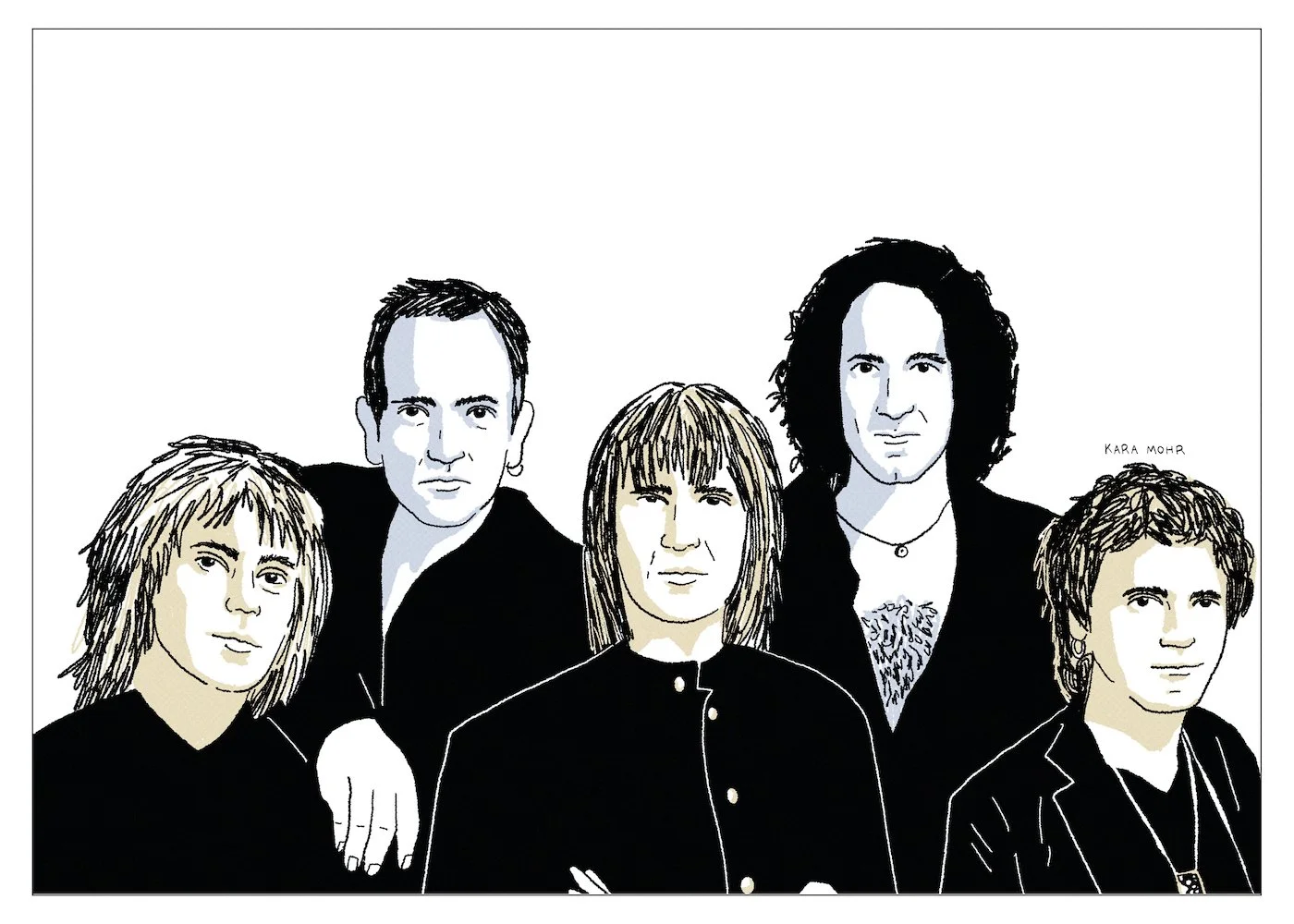

Def Leppard “X”

Def Leppard were once as American as apple pie. More than Bruce or Petty or Johnny Cougar, they were the soundtrack of the American Heartland. They were the grist for Rock radio, churning out pristine, semi-heavy, fully melodic singles, engineered by the future Mr. Shania Twain. With the arrival of Grunge and Alt, however, came the annihilation of Hair Metal. And though they did not precisely fit the genre, Def Leppard was a casualty of the 90s. On the brink of extinction, they tried everything to survive. They tried sounding like Stone Temple Pilots. They tried sounding like themselves. And then, finally, desperately, they tried the unthinkable. They hired wunderkinds Marti Frederiksen and Max Martin and made a bunch of tracks that resembled the third best songs from “American Idol,” if recorded by Bryan Adams for the Nordic market. On “X,” Def Leppard tried mightily to reclaim lost ground, but ultimately fell short of “popular” and landed awkwardly in the neighborhood of “pop.”

Art Garfunkel “Scissors Cut”

From 1970 through 1973, Art Garfunkel was among the most fascinating men in America. Coming off of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” he turned his attention to acting, where he made his debut in Mike Nichols’ “Catch-22.” The next year, he was nominated for a Golden Globe for “Carnal Knowledge.” Eventually, though, he reemerged as a solo recording artist. “Angel Clare,” from 1973, produced two top forty singles, and a series of Gold and Platinum-selling albums soon followed. What began as warm possibilities, however, devolved into flaccid melodies and artistic stagnation by the end of the decade. And then, tragically, Garfunkel’s romantic partner of many years, Laurie Bird, committed suicide in 1979. Most of America was depressed in 1979, but Art Garfunkel was more depressed. 1981’s “Scissors Cut” is the evidence of that depression — a bawling, private eulogy, pressed onto vinyl. It was also the end of “Art Garfunkel, Pop Star.”

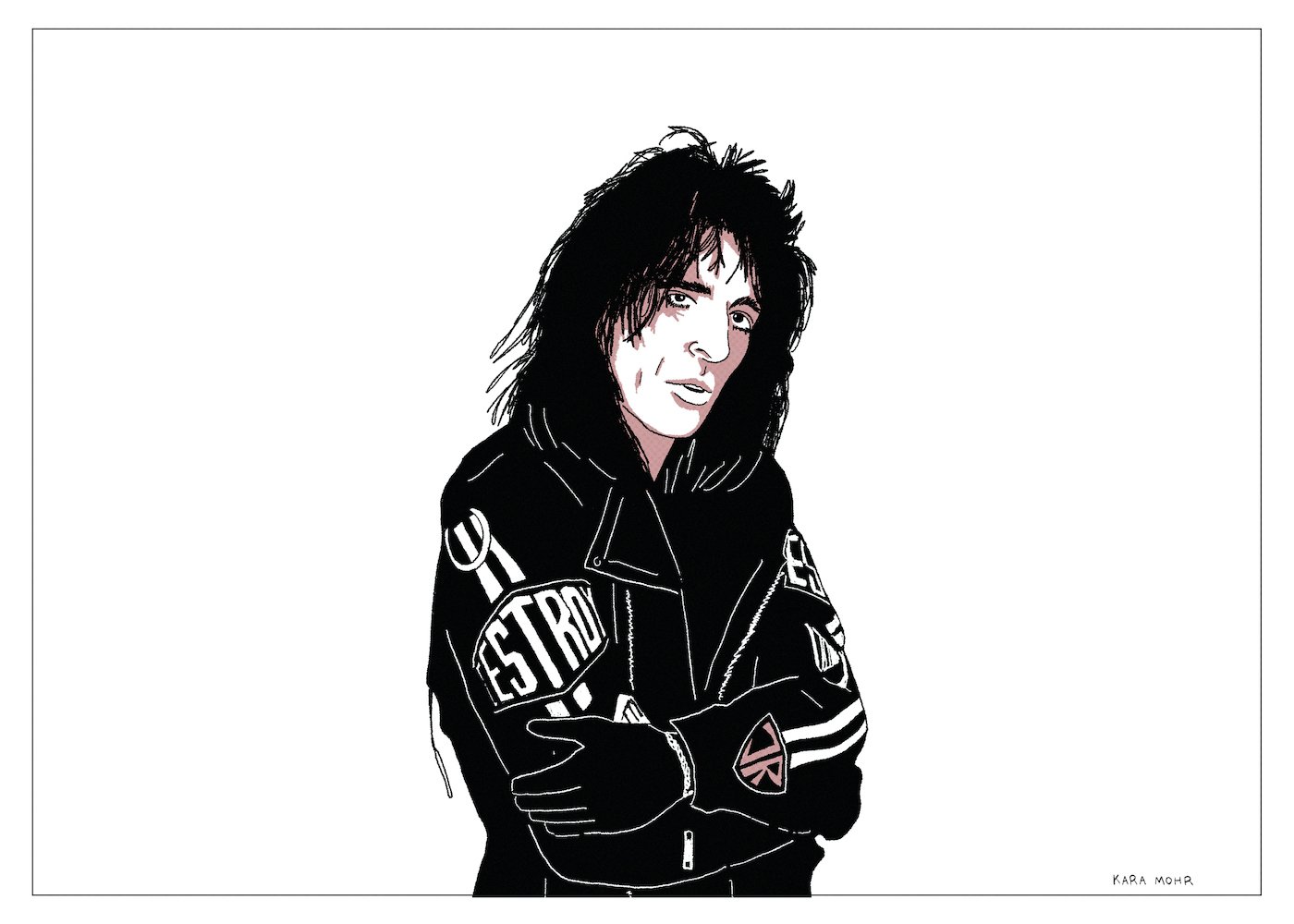

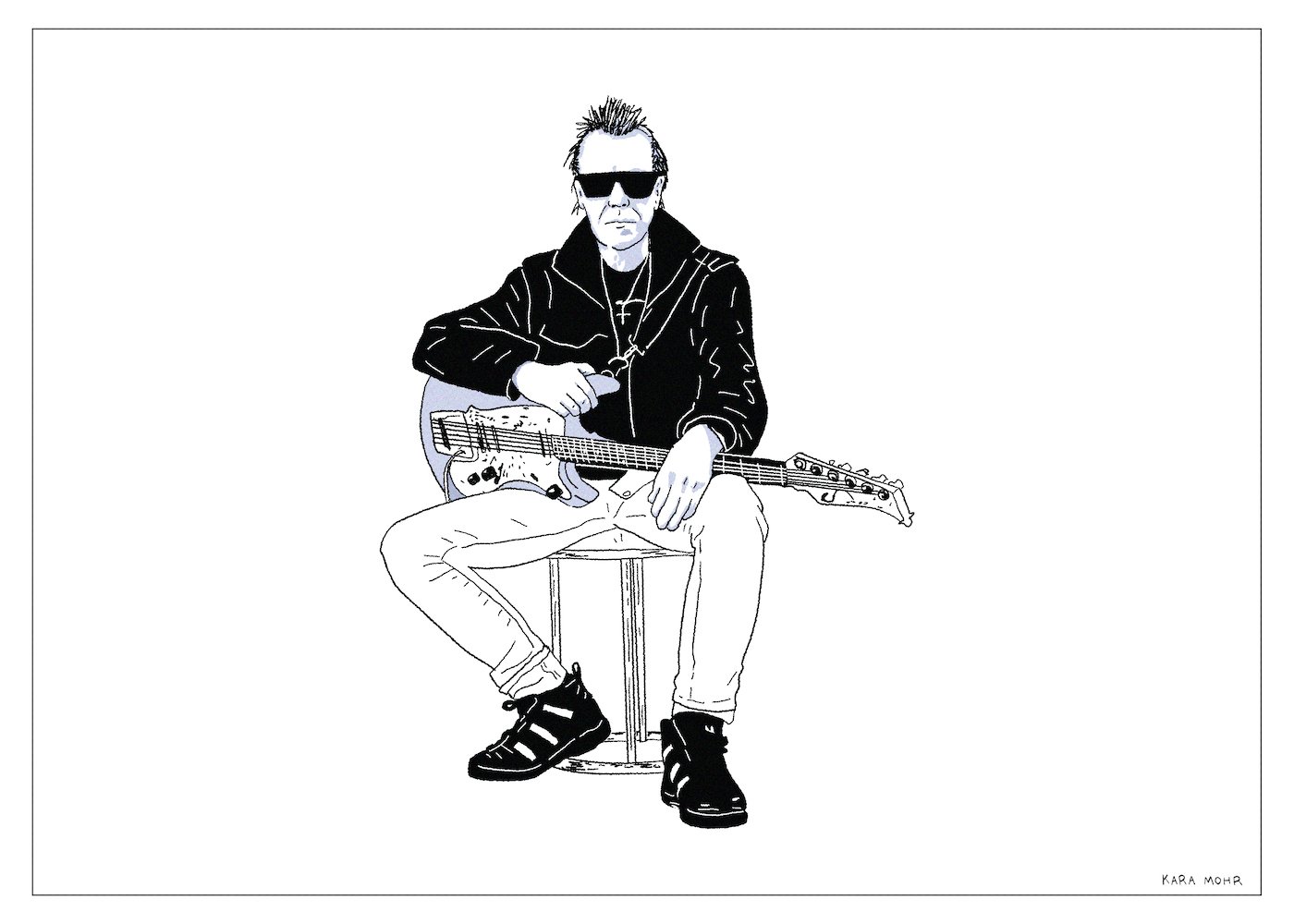

Link Wray “Barbed Wire”

After a dormant decade living a quiet life on a remote island in Denmark, the man who’d invented Hard Rock discovered his new sound. Amazingly, sixty-something Link Wray was faster, louder and scarier than his younger self. Whereas “Raw-Hide” and “Rumble” were soundtracks to noirish Westerns, his final performances sound like The Replacements scoring a 1950s drag race. Flanked by a band of much younger devotees, Grandpa Link returned to salvage his legacy. In spite of his indisputable greatness, he’d failed as a pop star. Failed as a folkie. And failed as a proto-punk. So, this time out — his last time out — he opted for all three incarnations. He wore black sunglasses, a leather jacket, a white tank top and a two foot ponytail and a thinning pompadour. He looked as though he’d either lost his mind or that he meant business. Or possibly both.

Cheap Trick “Cheap Trick”

The idea of a “return to form” is nothing new. Neil Young’s “Freedom” was his “return to form.” So was Clapton’s “Journeyman.” Dylan has probably “returned to form” half a dozen times in his career. The implication is the same: that some beloved, aging artist who had lost their way was finally making great music again -- music that confirmed their original brilliance. In 1997, ahead of their thirteenth studio album, writers and publicists were insisting that Cheap Trick’s latest was a return to form. Fans came out from the woodwork. Nirvana and Smashing Pumpkins and Weezer portended the event. Cheap Trick had found their way back. The band that Mike Damone and millions of Japanese teenagers once loved was coming back to get their due. But for a group whose success was so fast and so fleeting, and whose last hit was a hairy, ten year old power ballad, it was fair to wonder: what form were they returning to, exactly?

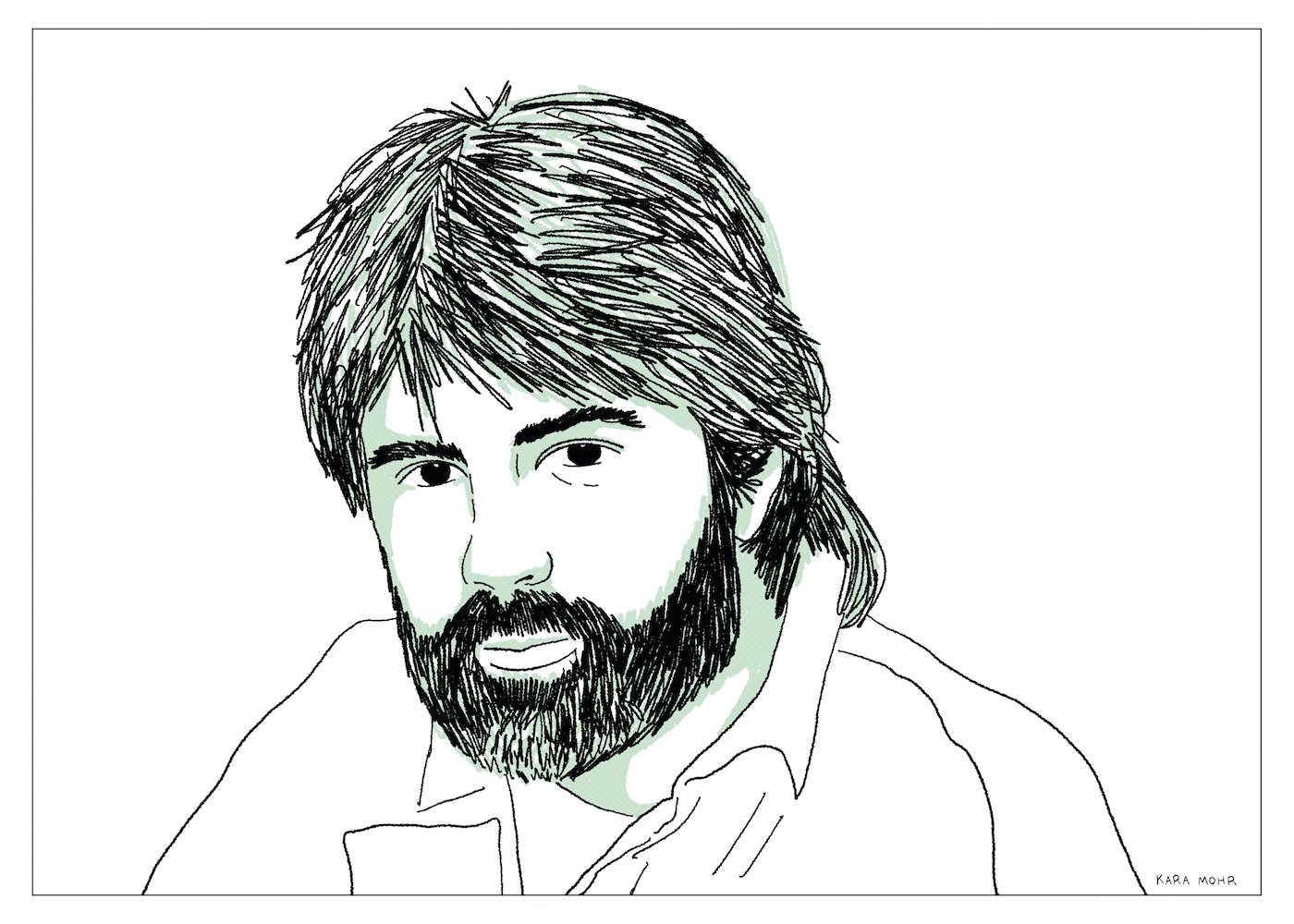

The Doobie Brothers “Brotherhood”

Today, they are the butt of a joke that started as an internet meme. They signify an amalgam of 1970s idealism, kitsch and grooviness alongside early 80s cool, coked up excess. All because of four albums they released between 1976 and 1980, and because of Michael McDonald’s proximity to Steely Dan, Christopher Cross and Kenny Loggins. Because of that, The Doobies are Twitter jokes and Spotify playlists more than they are “China Grove,” “Black Water,” “What A Fool Believes” and the bootlegging scandal from “What’s Happening!!” For nearly a decade, however, they were the American monoculture. Not The Eagles or Fleetwood Mac or M*A*S*H. The Doobie Brothers. They were the opposite of a punchline. The opposite of any one thing. They were everything. Then, one day, everything became too much and they were gone. By the time they came back, everything had changed. Everything, except The Doobie Brothers.

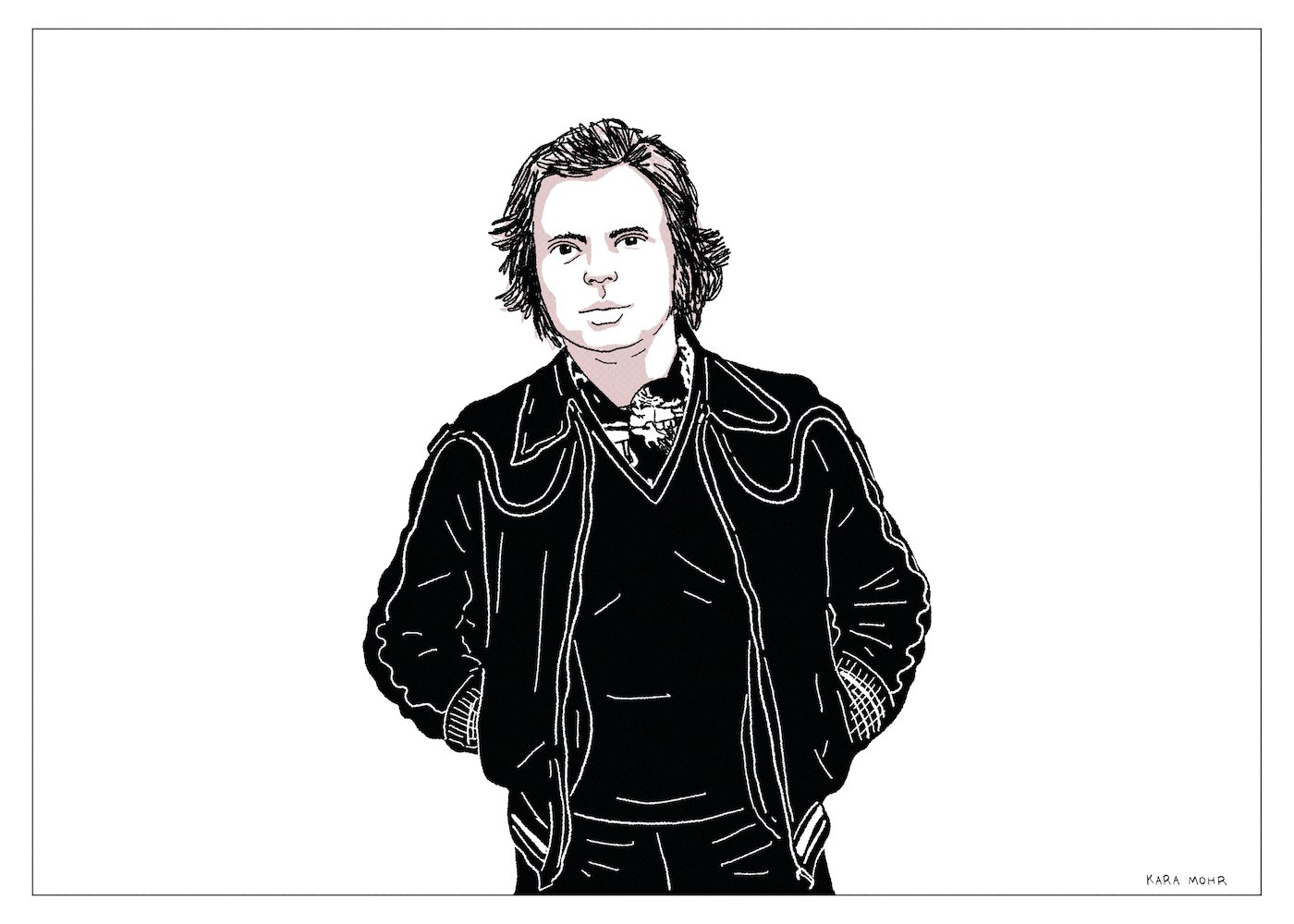

John Fogerty “Revival”

Truth matters. Of course. But on the other hand — and especially in the curious case of John Fogerty — who the hell knows? Was he the Mark Twain of his generation or the Atticus Finch or was he just the guy who connected the musical dots between Ricky Nelson, Little Richard and Neil Young? How did the man who was once our answer to Paul and John just one day just disappear? As spectacular as Fogerty’s early run with Creedence was, everything that followed seemed like an unsorted mess. Seriously, what happened? Was he impossible to deal with. Did his muse dry up? Why was he always in court? Who was the hero and who was the villain? Time resolved some things. Lawsuits were settled. Contracts expired. People died. And, of course, John Fogerty had his beloved, if still perplexing, second act.