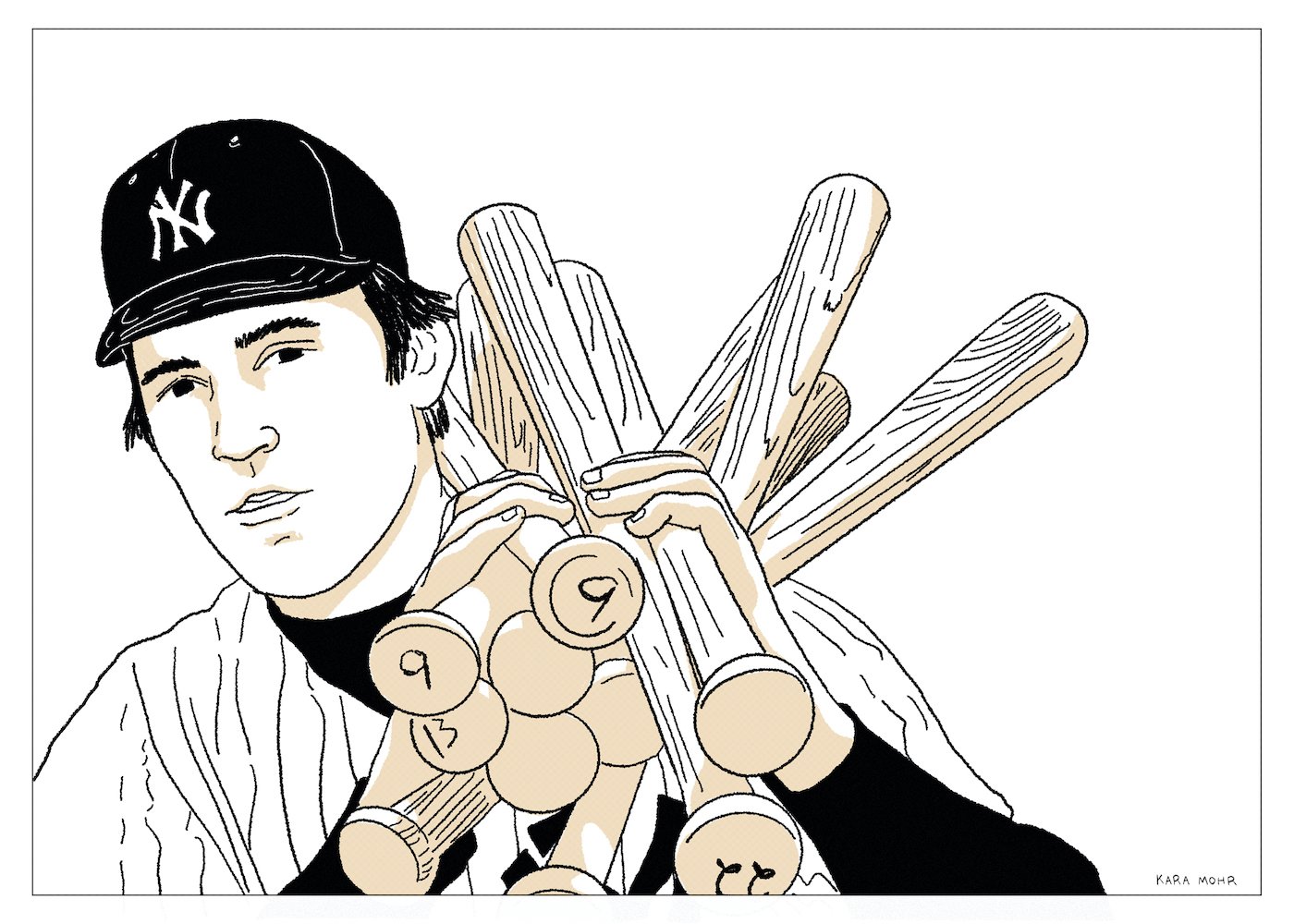

Steve Garvey “Mr. Clean”

He was considered the surest of sure bets — as American as apple pie, as handsome as any movie star and as natural as Roy Hobbs. Steve Garvey was the clean living, god loving, good looking MVP at the heart of The Dodgers batting order. But also, his appeal went far beyond his All-Star performance on the field. He was “Captain America.” Square jaw. Not a hair out of place. Biceps and forearms that resembled spinached-up Popeye. And, what’s more, he was married to Barbie! Steve and Cyndy Garvey were Hollywood’s heroes during Reagan’s “Morning in America.” Until, once day, things got bad. And then worse. And then much worse. Until those nicknames became ironic chuckles. Until Steve Garvey became a reminder that the only thing America likes more than a rags to riches story is a riches to rags story.

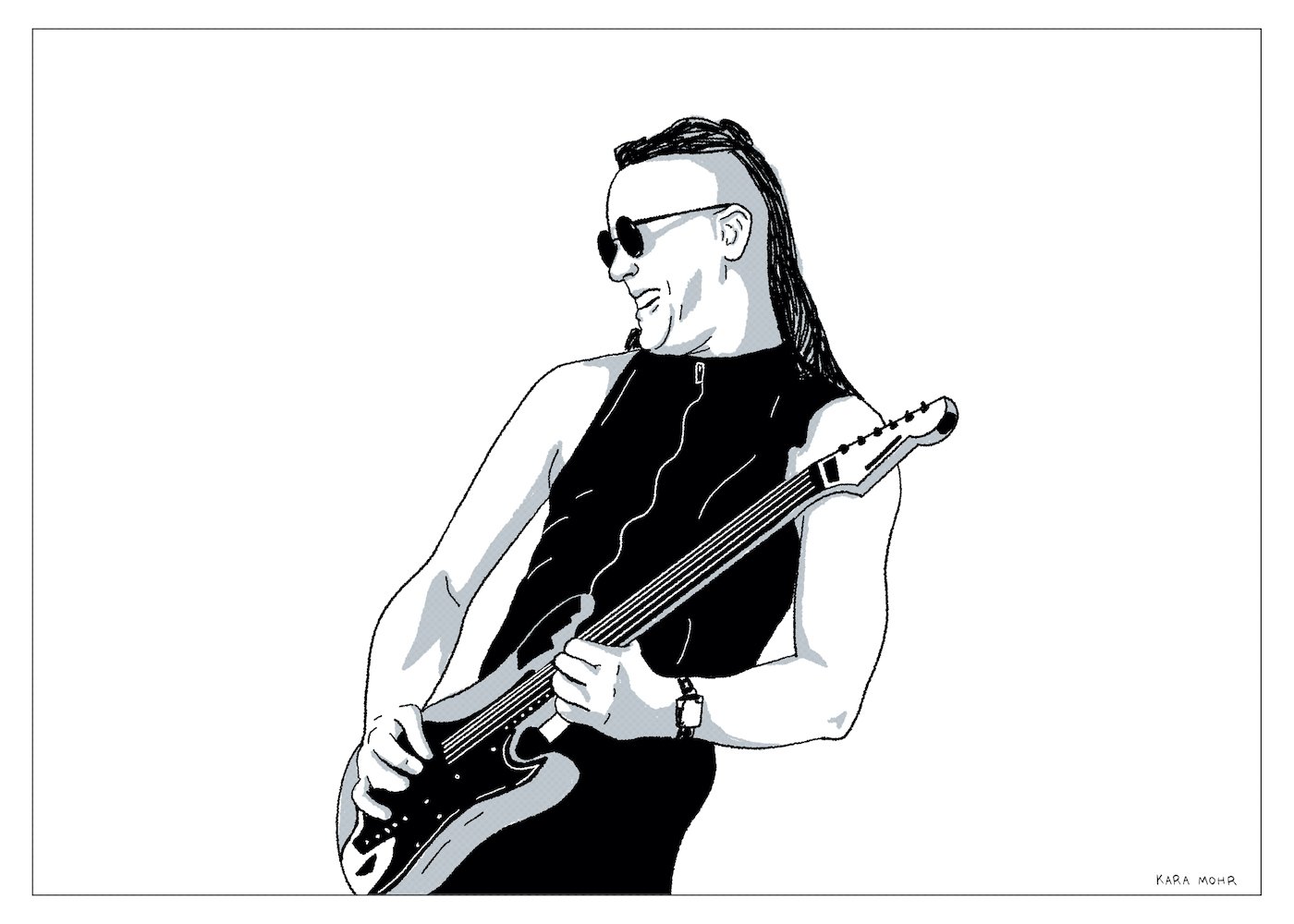

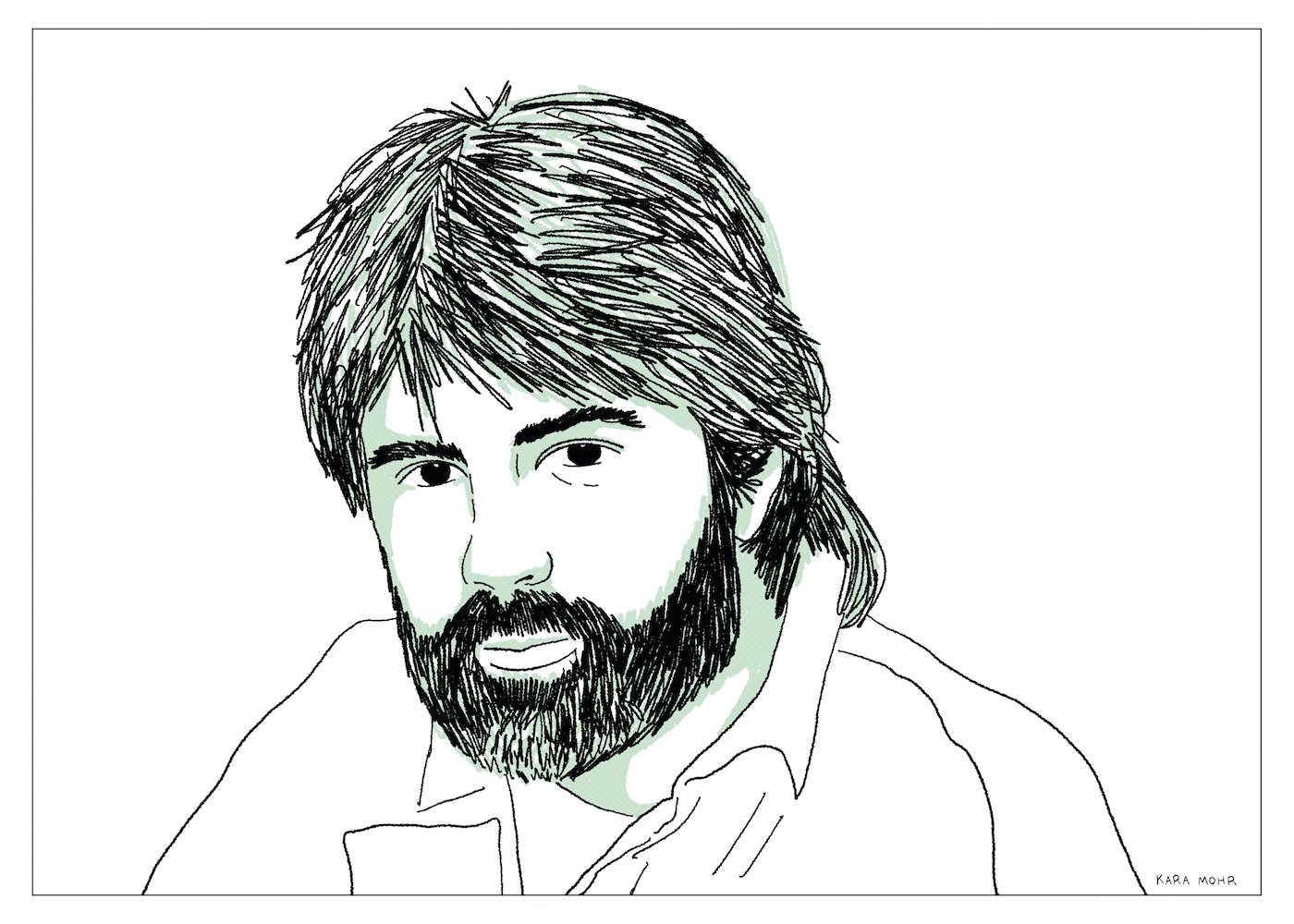

Todd Rundgren “No World Order”

By 1992, Todd Rundgren — the guy who kind of, sort of invented Power Pop, who sang like Carole King, who could play any instrument, and who made Meat Loaf sound like a bat out of hell — was a middle-aged, former Rock star, former producer, father of two living in Marin County, California. If he’d proven anything during the previous decade, it was that he was deeply interested in the intersection of music and technology and largely disinterested in his own commercial prospects. Which meant that, if you were Warner Brothers Records, based in Burbank, California, and trying to sell a lot of albums, you probably wanted to steer clear from him. But, if you were Philips Electronics, based in Amsterdam, and you wanted to promote your new CD-i (compact disc interactive) players and discs, Todd Rundgren was definitely your guy.

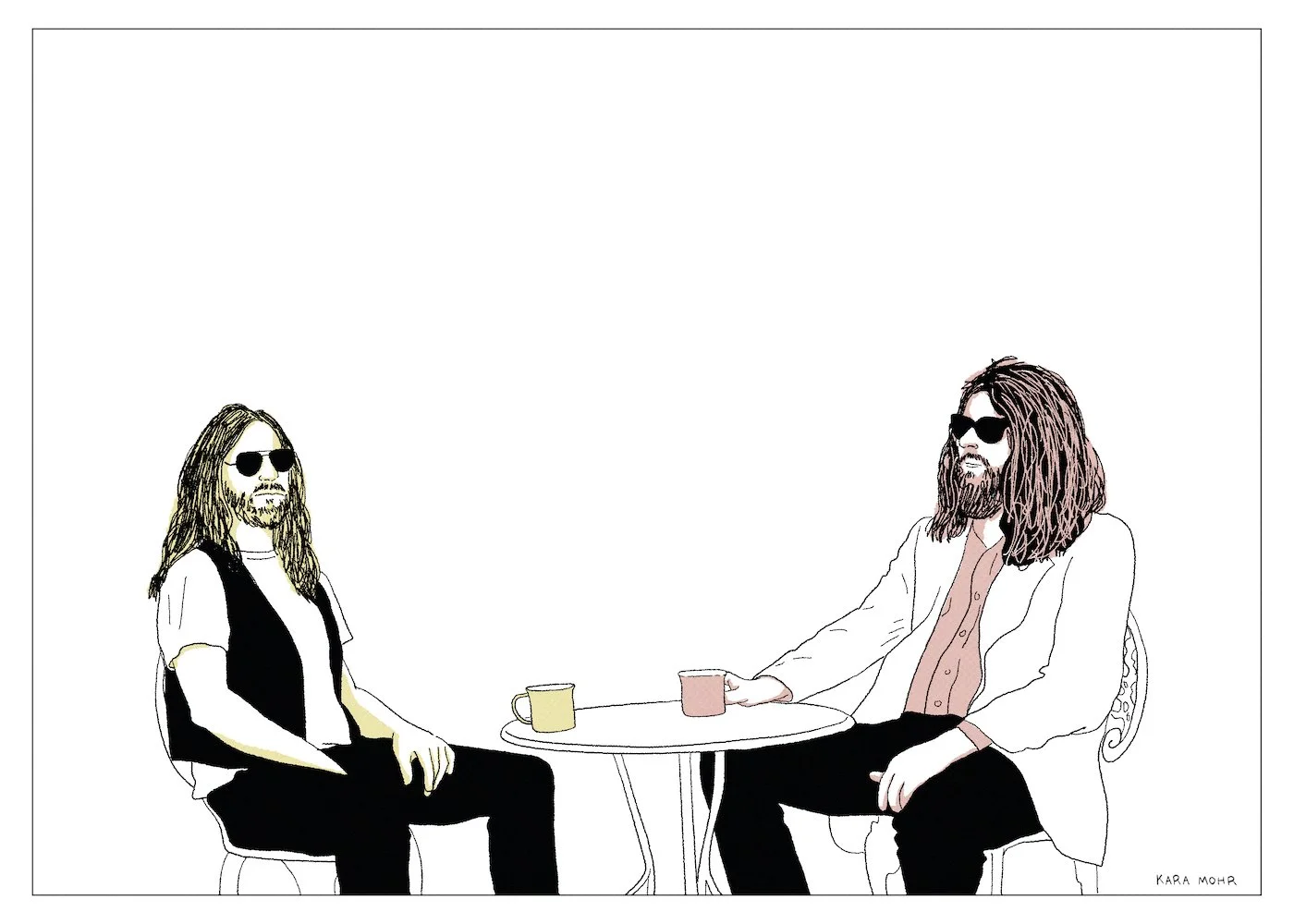

Third Eye Blind “Dopamine”

In his “60 Songs That Explain The 90s” podcast, right after the Sinéad O'Connor episode but before the Pavement one, Rob Harvilla tries to unpack the maddening, intoxicating mystery of “Semi-Charmed Life.” During the back half of the show, Harvilla is joined by Max Collins of Eve 6, and together the duo pierces the veil of Stephan Jenkins — Collins’ former tour-mate and nemesis. After some obligatory Jenkins-slagging the two conclude that, in spite of the singer’s limited vocal range, terrible pitch, decimated falsetto and borderline personality, “Semi-Charmed Life” works. In fact, it more than just works — it thrills. In fact, it thrills because of those defects. Through that lens, I began to reframe Jenkins not as a cad or a villain but as a fully realized talent. The Beatles were preternaturally gifted. The distance between their potential talent and actual talent was perhaps not so great. Jenkins, on the other hand, was a vain dick who could only barely sing, but who had a knack for making songs sound like hits and making narcissism sound universal. What if “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” wasn’t the miracle? What if “Semi-Charmed Life” was?

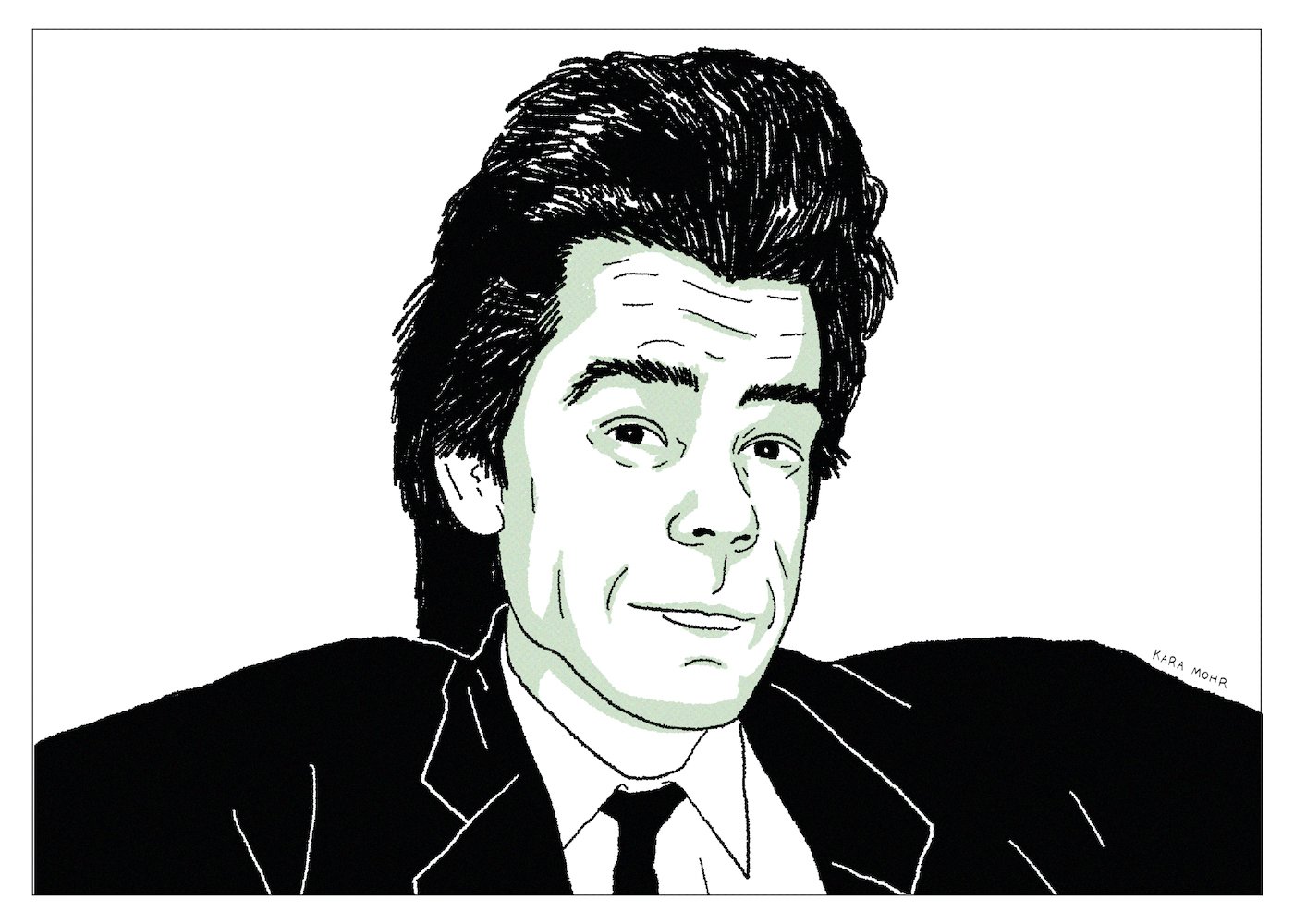

Boz Scaggs “Other Roads”

Though today he is known as a Steely Dan adjacent, dollar bin staple, Boz Scaggs is truly a man of many gifts. He possesses a soulful tenor, dipped in Van Morrison and glazed in Al Green. He has a knack for arrangements, for knowing when to let a song skate around and when to bring it back home. But his forte really seems to be some combination of a casual, Northern California vibe alongside the steely precision of his playing. Boz made music that might not thrill, but would almost always delight. It was music that thrived just in front of the background. There was really no one like Boz Scaggs. He was more successful than he was famous, though he was, for some time, also famous. He was also the kind of star who made the kind of music that could have only succeeded between 1976 and 1980. As a result, his celebrity was short lived. Once the calendar turned to 1981, Boz disappeared for seven long years. The guy that returned was less a Rock Star and more a Bay Area impresario. Well dressed. Wine curious. Affluent. Self-assured. Still totally casual and completely precise.

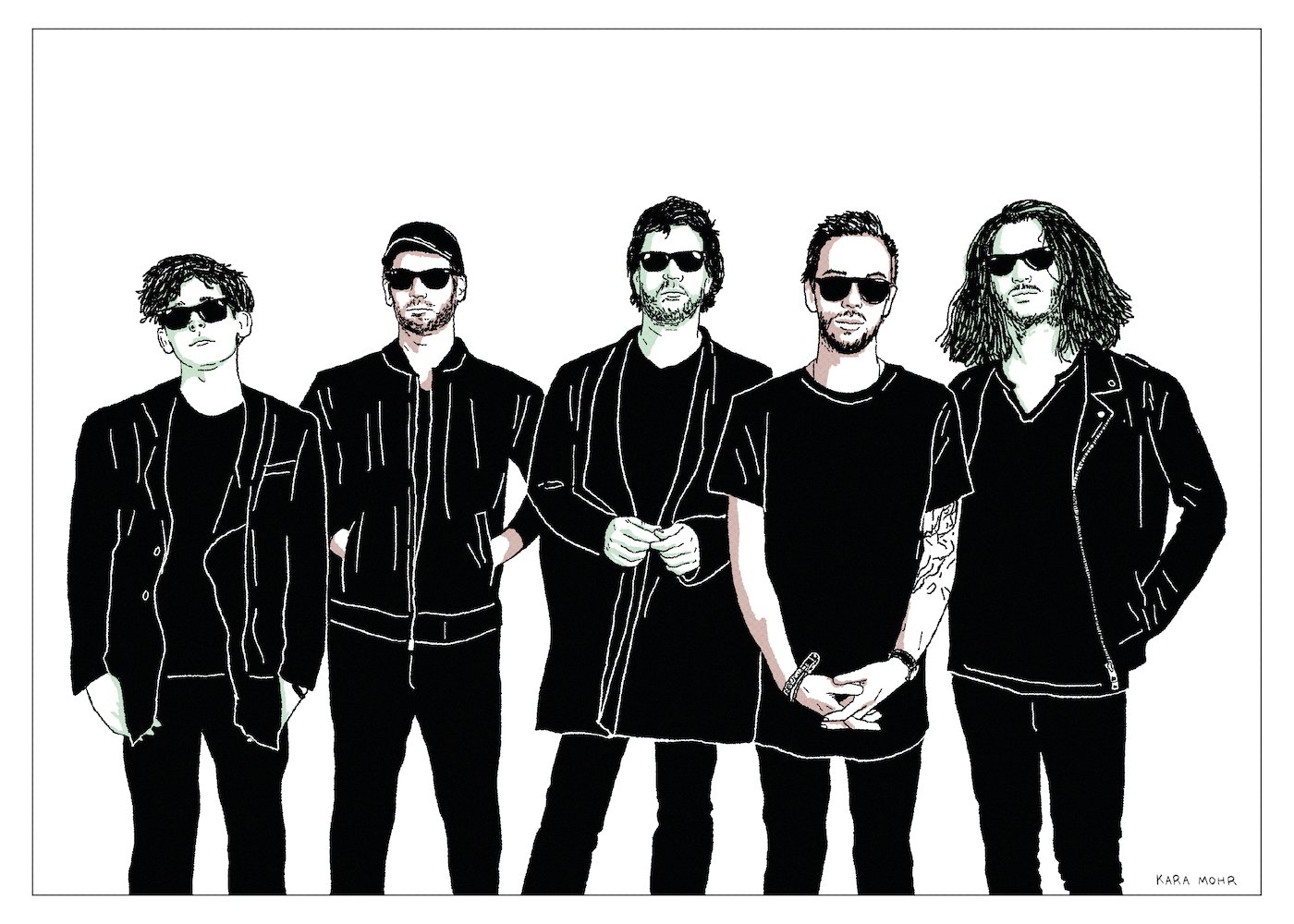

The National “The Album Covers”

As a general rule, masterpieces rarely have awful covers. Inversely, bands simply do not produce masterful album covers when their music is stagnating. For instance, The Stones’ covers get real spotty after “Emotional Rescue.” “Steel Wheels,” in particular, is an embarrassment. Somehow, Van Morrison’s septuagenarian covers are even worse than The Stones — much worse. “Latest Record Project” is a craven insult to the form. But Van and The Stones are not outliers — they’re the norm. Years after their commercial peaks, when they have little to gain and so much to lose, cover art is almost always the first thing to go. The National, however, are the exception to the rule. With each new album, their cover art and design continues to dazzle in ways that betray the depression of their songs and the uncertainty of their albums.

Graig Nettles “Vigilante”

First off, his name is Graig. G-R-A-I-G. It’s not Greg or Gregory. And it’s not Craig. Graig, with two G’s has more teeth than Greg or Craig. Graig looks possibly Welsh or Gaelic and like it wants to have more than one syllable. It’s a name that has caused confusion for decades, spawning baseball card typos and debates among young Yankee fans back in the day. And yet, in spite of its oddness, there’s no other name that would have worked. Of the twenty plus thousand people to have played major league baseball, only one is named Graig. Moreover, etymology suggests that “Graig” roughly means “vigilant.” And while Graig Nettles was many things on the field — an elite fielder and a perennial home run threat — and many more things off the field — a brawler, a rule bender, and a loyal teammate — he was absolutely nothing if not vigilant.

Michael McDonald “Blink of an Eye”

There’s an aphorism that goes something like, “Brad Pitt is a character actor in a leading man’s body.” In music, there’s no direct equivalent for the Pitt aphorism. There are, of course, shy or mercurial singers — Bob Dylan and David Bowie fit that bill. But, solo artists, almost by definition, cannot be reluctant frontmen because they have no “back” to blend into. They are not part of a group — they are the show. The same applies to lead singers in bands, albeit for different reasons. There is really no such thing as a grudging frontman. A lead singer has to want it. Privately, they can be shy and awkward like Farrokh Bulsara, but when they hit the stage they have to be Freddie Mercury. That’s how it works. But, like all statutes, there are very rare exceptions. In the case of Rock and Roll frontmen, there is one indisputable outlier — a guy who sounds like Bob Seger and Darryl Hall at the same time. Who, once upon a time, looked like the love child of bearded, post-Beatles McCartney and a soul puppy. A guy whose voice is as rich as a yacht but who always preferred to be in the background, heard more than seen.

Black Mountain “IV”

Ten years, three studio albums and a half dozen side projects after their Pitchfork-feted debut, Black Mountain returned with “IV.” From its Hipgnosis-inspired cover, which screams Floyd and Hawkwind, to its bank of synthesizers, borrowed from Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson, “IV” is a total flex. It’s an epic album, daring and ridiculous enough to take its name from one of the most famous albums in the history of Rock and Roll. Black Mountain’s “IV” is obviously not Led Zeppelin’s “IV.” In fact, it’s their least bluesy, least metal, most spacey and most proggy album. A more accurate title might actually be “Light Side of the Moon.” The titanic riffs are still very much there, but they are not the thing. The synthesizers are sometimes the thing, but also not the thing. The thing that distinguishes “IV” from straight homage is the thing that has always separated Black Mountain from everyone else — the sound of Amber Webber’s voice paired with Stephen McBean’s. The sound of verdant soil and deep roots next to burnt twigs and leaves.

Blues Traveler “North Hollywood Shootout”

On so many levels, our aversion to Blues Traveler is ridiculous. Of all those Nineties Jam bands, why them? There were many lesser variations. Bands who couldn’t play with singers who couldn’t sing and jams that went nowhere. Blues Traveler was barely any of those things. They were a solid Roots Rock band with a mascot for a lead singer; far more exciting than their closest predecessor — Spin Doctors — and their more successful, distant cousin — Hootie and the Blowfish. If anything, their brief apex was a fluke — a product of commercial radio’s (and MTV’s) inability to separate Beck from Better than Ezra. For one strange moment in 1994, Modern Rock, Mainstream Rock, Pop and Adult Alternative formats all sounded oddly similar — jangly and towing a line between earnest and ironic. Basically, like the sound of Blues Traveler. On the other hand, reducing them to a bad haircut, does a grave injustice to the band. It also obscures the harmonica in the room — the dozens and dozens of harmonicas in the room.

Buster Pointdexter “Buster’s Spanish Rocketship”

The prevailing discourse has always been that Buster Pointdexter was “the act.” That the tuxedo, giant pompadour, martini glasses, Jump Blues, and Eighties Club Med by way of Fifties Havana vibes was David Johansen having a go at everyone. That ten years after the demise of The Dolls — the world’s greatest band that never had a chance — and years after working his way around the world with the David Johansen Band and ending up exactly where he started (nowhere), he needed to make us laugh so we wouldn’t cry. Buster Pointdexter was supposed to be a serious good time, but also in no way serious. It was a gag. A costume. Closer to Tenacious D than to The Dolls. But what started out as a lark — a mildly embarrassing side hustle even — became a career. What’s more, Buster was not a phase. He was not an alter ego or an id. Looking back now, Buster Pointdexter was the thing.

Greg Luzinski “The Bull”

Baseball has provided us with a handful of quirky, if semi-validating, proof points for the theory of “nominative determinism” — the idea that a person’s name somehow determines their livelihoods. There’s Cecil and Prince “Fielder” (neither of whom were known for their gloves). “Homer” Bailey and “Homer” Bush (the former a pitcher, the latter not exactly a slugger). Maybe Rollie “Fingers” qualifies (admittedly a stretch)? How about Grant “Balfour” (ball four)? Those rare examples are all well and good, but also confirm that ballplayers are personified less by their names than by their nicknames. “Charlie Hustle.” “Hammerin’ Hank.” “Steady Eddie.” These, much more so than first or last names, predicted the destinies of their owners. However, in the roughly one hundred and fifty years of professional baseball, no nickname has better suited its player than Greg “The Bull” Luzinski — a colossal man, put on this earth to annihilate baseballs and, one day, sling BBQ.

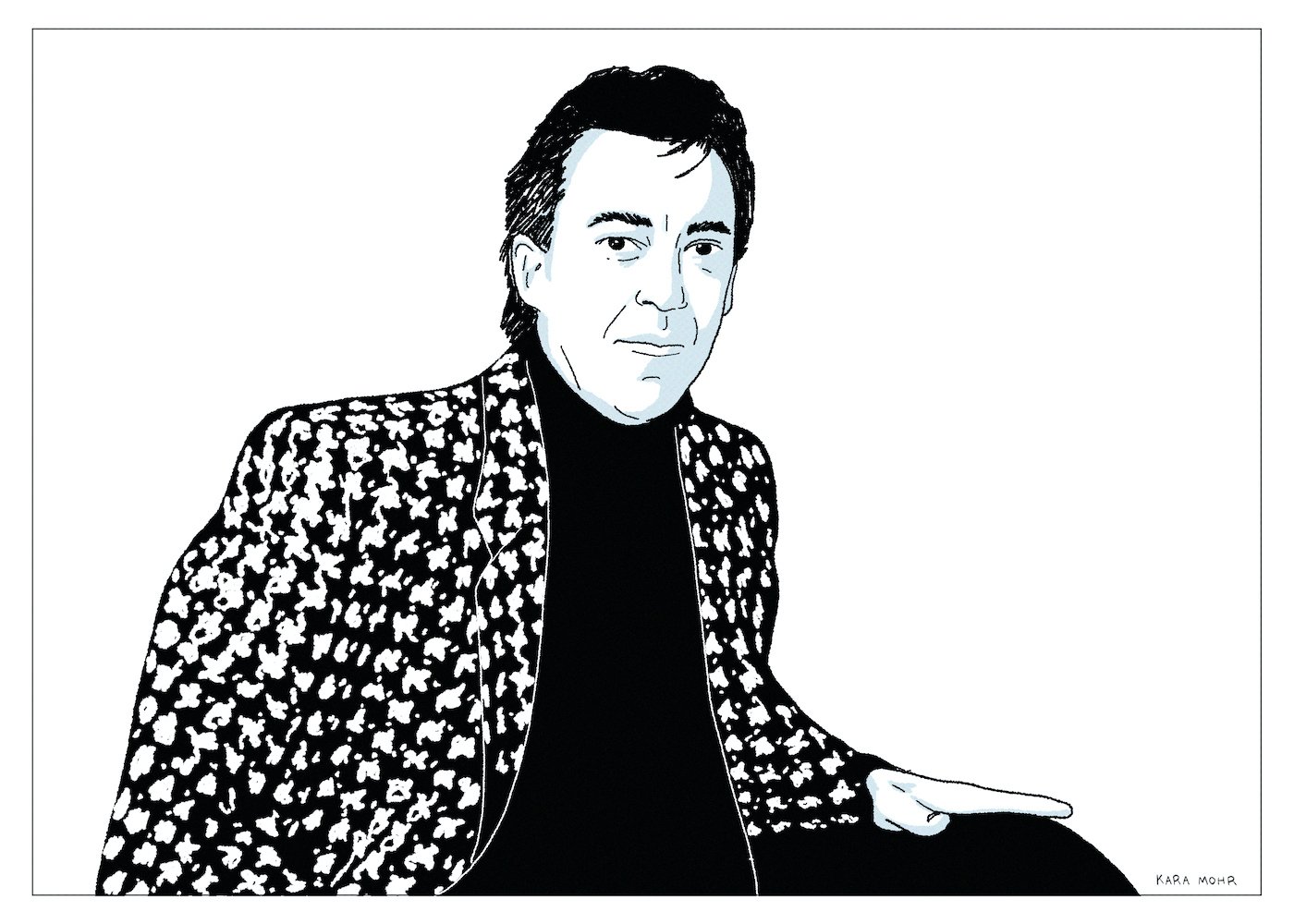

Ray Davies “Americana”

As a musical style, Americana suggests something in between “Roots Rock” and “Alternative Country.” Stylistically, it's a fertile if ultimately narrow genre. But, Ray Davies’ “Americana” is not Whiskeytown’s “Americana.” Davies’ is as expansive as it is deep. It considers both the United States of America and the land mass that predated the country — the massive mountain ranges and the canyons and rivers and the natives and the cowboys. The freedom and independence and capitalism and Jazz and Blues and Soul. The New York and Los Angeles and high hopes and dashed dreams. All of it. The man who wrote “A Well Respected Man,” “Waterloo Sunset” and “Village Green Preservation Society” — the singer-songwriter who satirized and romanticized English life was enraptured with America. England consumed his mind, but America held his heart.

Ted Leo “The Hanged Man”

From 2000 through 2010, Ted Leo was the mainest of Indie Rock mainstays. He and his band released a string of reliably thrilling albums, distinguished by his breathless tenor and progressive politics. Ted Leo and The Pharmacists were so excellent, in fact, that it seemed a foregone conclusion he would one day break through. That Ted Leo would eventually be an important, prestige act felt inevitable. After all, they had their Billy Bragg and their Elvis Costello, so we could have our Ted Leo. He was simply too good — too musical, too smart and too hard working — to imagine any alternative. The sparkling reviews continued along with the steady uptick in sales, until he reached the height of sub-popularity. And then, just when we assumed something monumental was about to happen for Ted Leo, it did. But it was not at all what anyone expected.

Van Morrison “The Album Covers”

Before he became a craggy, portly Soul man in fedoras and suits, before he was a grumpy anti-lockdown militant, before the Skiffle record and the Facebook rant and a song so profoundly sad (“Pretending”) that it was somehow more depressed than his song about walking out on a friend with tuberculosis (“T.B. Sheets”), before the healing and the silence and the hymns, and before he stuffed himself into that stretchy leisure suit get up for “The Last Waltz,” George Ivan Morrison cared deeply about his album covers. But that was then. Today, Van survives as the artist whose album cover art most betrays the product contained within. His obsession with “tone” and “feel” is surpassed only by the depth of his disdain for the art that adorns his music.

Styx “Brave New World”

Like Queen, with whom they’ve often been compared, Styx has always been the kind of band that swings for the fences. Most of the time they whiff — but in a charming “love the effort” sort of way. When they connected, however, as they did roughly one time per album between 1973 and 1982, they hit it out of the park. Way out of the park. During that run, DeYoung, Shaw, Young and the Panozzo brothers scored a half dozen top ten hits and five consecutive platinum-selling albums. And yet it always seemed to me that the band was a mistake — that we already had Queen and Journey. That DeYoung should be wowing audiences on Broadway (which he eventually did) and that Shaw should be fronting a Hair Metal band (which he also eventually did). By the end of the Nineties, seventeen years removed from the dystopian, sci-fi hit that broke the bank and the band, Styx were still swinging, but no longer connecting.

Dim Stars “Dim Stars”

Though it was released in 1991, “Dim Stars” sounds like New York City in 1988 — when Jon Spencer was fronting Pussy Galore and before Sonic Youth got a major label deal and when Avenue A was still sketchy and when everything stunk of imminent recession. Like all of those other things, you could call “Dim Stars” loose and offhanded, or you could call it sloppy. You could call it artful or avant garde, or you could say that it sounds like shit. But in fact, it really sounds like four different things. One, like Sonic Youth with Richard Hell splitting the difference between Thurston and Kim. Two, like a poorly made sequel to “Destiny Street.” Three, like an overqualified Scuzz Rock band that had not yet found its groove. And, finally, like a post-structuralist hipster cover band.

Billy Preston “You and I”

If 1979 marked the end of Billy Preston’s run as a Pop star, it was a beautiful finish. “Late at Night,” his first record for Motown and his last of the decade, found The Fifth Beatle after dark, conjuring a quiet storm. “With You I’m Born Again,” the album’s hit single, was a duet with Syreeta Wright that explained everything from Barbra Streisand to Luther Vandross. By 1982, however, “Billy Preston the superstar” was done. Lionel Richie, Prince and, mostly, Michael Jackson, had taken over his corner. The new music spigot was shut off. Guest work dried up. And, one day, the ubiquitous sideman found himself buried under a mountain of cocaine and bad decisions. And so, in 1997, as legal and financial problems mounted and rumors and innuendo swirled, Preston escaped six thousand miles from the bright lights of Hollywood into the open arms of a past prime Italian Electro Pop group named Novecento.

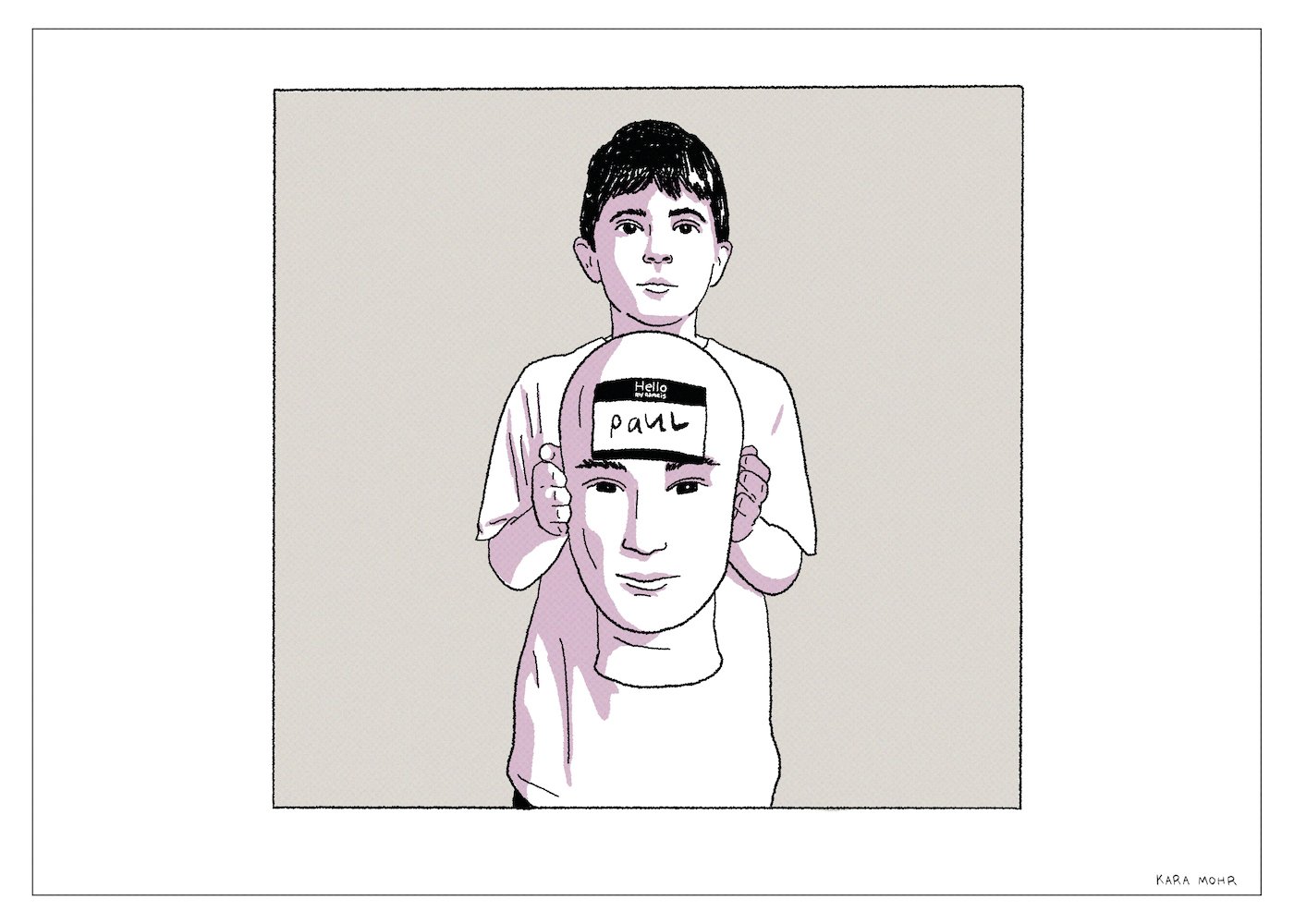

Rob Thomas “Chip Tooth Smile”

While I have been guilty of my fair share of Matchbox Twenty eye rolls, I was also guilty of not really knowing much about the band. They were always something of an enigma to me — a mystery that I couldn’t shake. Except, it wasn’t really the band I was interested in — it was their frontman, Rob Thomas. I had read all the facts (Wikipedia) and heard all the albums (four with Matchbox Twenty and four solo), but I still had zero clue. Was he more Adam Duritz or Ed Kowalczyk or Stephan Jenkins? Or was he my generation’s answer to Phil Collins and Lionel Richie? Generally speaking, time is the enemy of Rock and Roll. But it’s a dear friend to writers. Time furnishes us with perspective and evidence. It reveals lies and truths. It separates bad style from bad music and characters from their settings. Also, as Rust Cohle once suggested, time is just a flat circle. Time was very much on my side as I followed the investigation to its logical conclusion — Rob Thomas’ 2019 solo album, “Chip Tooth Smile.”

Chain and The Gang “In Cool Blood”

Like Nation of Ulysses before them, The Make-Up were more legendary than popular. And so, just five years after they first appeared, the most stylish, most ideological band on the planet was dissolved. In the Aughts, Ian Svenonius (along with Michelle Mae and Neil Hagerty) formed Weird War, but because socialism might be bad for business, the singer spent most of that Aughts moonlighting as a subject slash contributor for Index Magazine — and anyone else who wanted his ideas and his hair for their pages. By 2009, he was more an essayist, a great interview, a great photoshoot, and a hipster cad than he was a rock and roller. He was to Vice what Fran Lebowitz was to Vanity Fair. Until one day — when he’d either run out of ideas or when he had too many out of them — Svenonius started another new band. Chain and the Gang started as a lower stakes, rotating cast of friends and acolytes, sponsored by Calvin Johnson. By then, fans (and critics) were familiar with Svenonius’ Post-Structuralist, Marxist provocateur shtick. What they were less familiar with was his winking, hip-shaking good times.

Squeeze “Cradle to the Grave”

Though early on they were compared to Lennon and McCartney, Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford were much closer to Elton John and Bernie Taupin. Tilbrook was a master tunesmith and Difford was an equally gifted wordsmith. For the most part, however, (and unlike Lennon/McCartney) they worked separately, fitting and refitting their own parts to the others’ material. Tilbrook, the more gregarious and intuitive one — he leaned towards the Beatles. Difford, more contained and cerebra, leaned towards Post-Punk. One man was blonde. The other brunette. They were childhood classmates, but, from the outset, and in spite of their shared interests, they were also a study in contrasts. During Squeeze’s first break-up, the two men actually made an album together, under their own names. After the second divorce, however, things got ugly. Jools Holland was gone, the hits dried up and Difford bottomed out. From the outside, it seemed certain that Squeeze was done. From the inside, it appeared even worse.