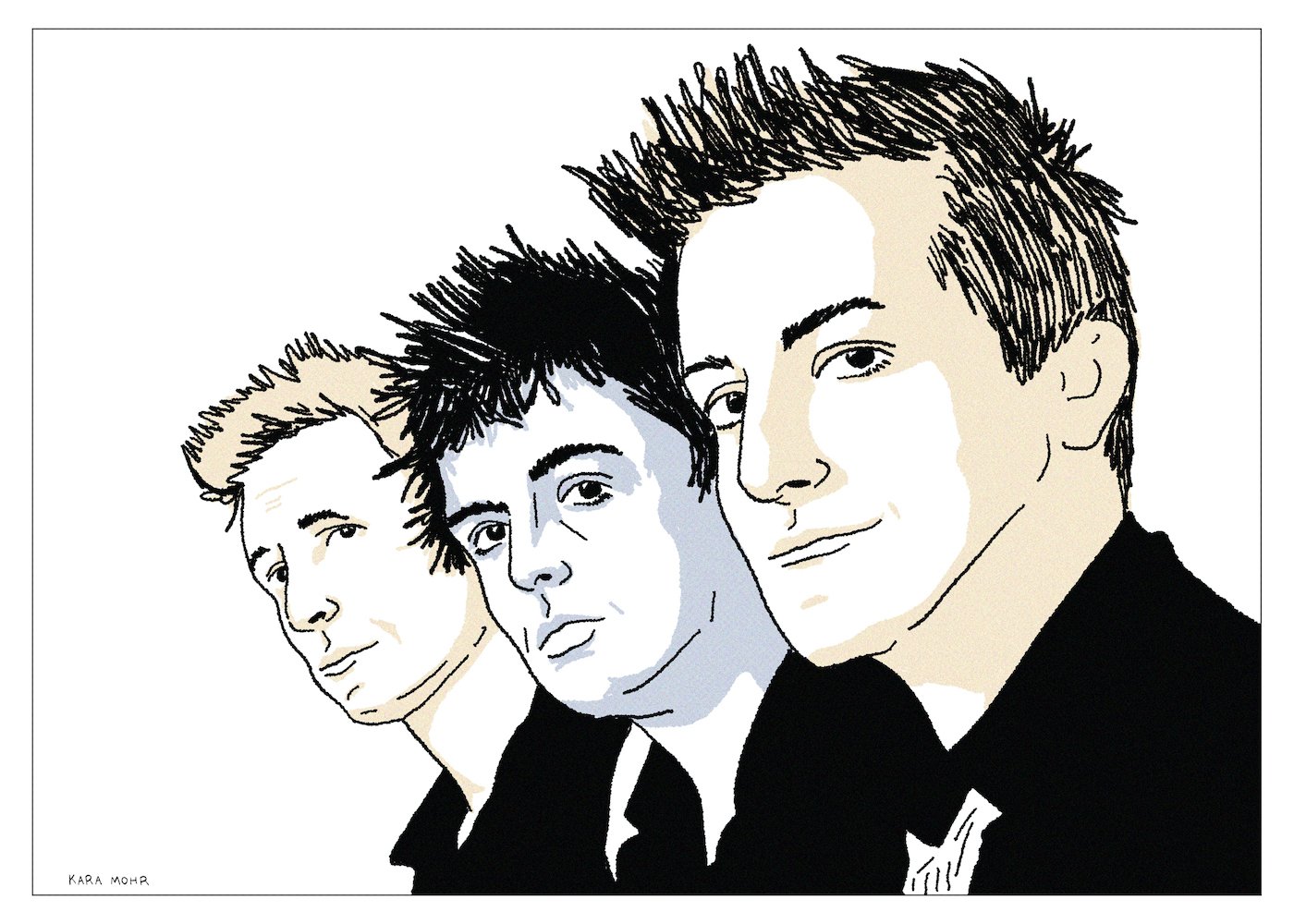

Green Day “Revolution Radio”

Twenty-two years after they first broke out with “Longview,” twelve years after they were the biggest Rock band in the world, eleven years after they inadvertently bankrupted Lookout! Records and four years after Billy Joe melted down onstage, Green Day was, once again, a band with uncertain prospects. And yet, their twelfth studio album was not a sharp turn or a step back or a leap forward. “Revolution Radio” was more a shoring up of lost ground — more like downside protection. All three members of the band were well into their forties by the time of the record’s release, meaning that the snotty charms of their youth would not play the same. Self-loathing and fuck you's present much differently in middle-aged millionaires than they do in twenty year olds. And so, in the year that Donald Trump was elected President and at a time when album sales were usurped by track steams, Green Day was in the unenviable position of having to question both their form and their function.

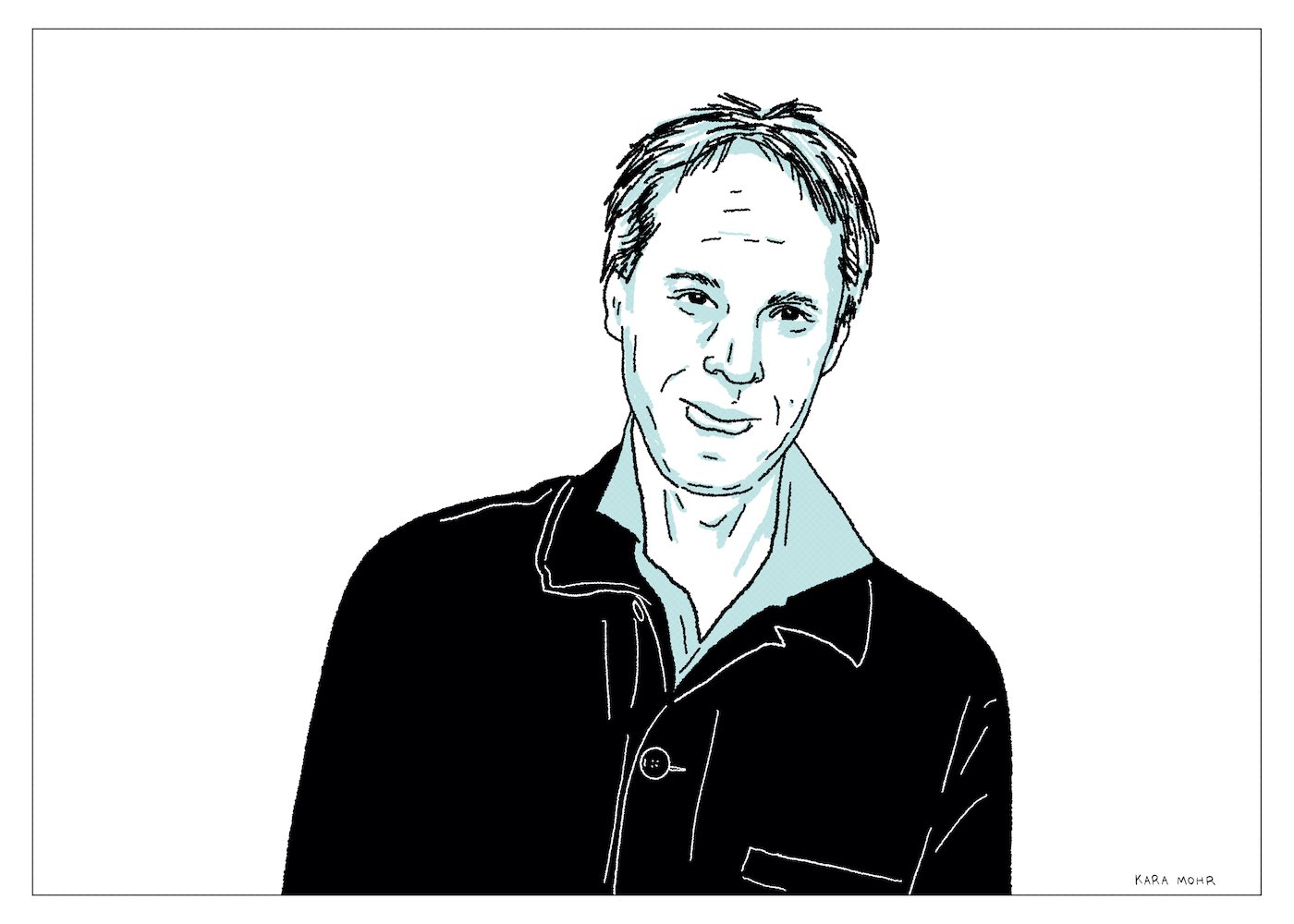

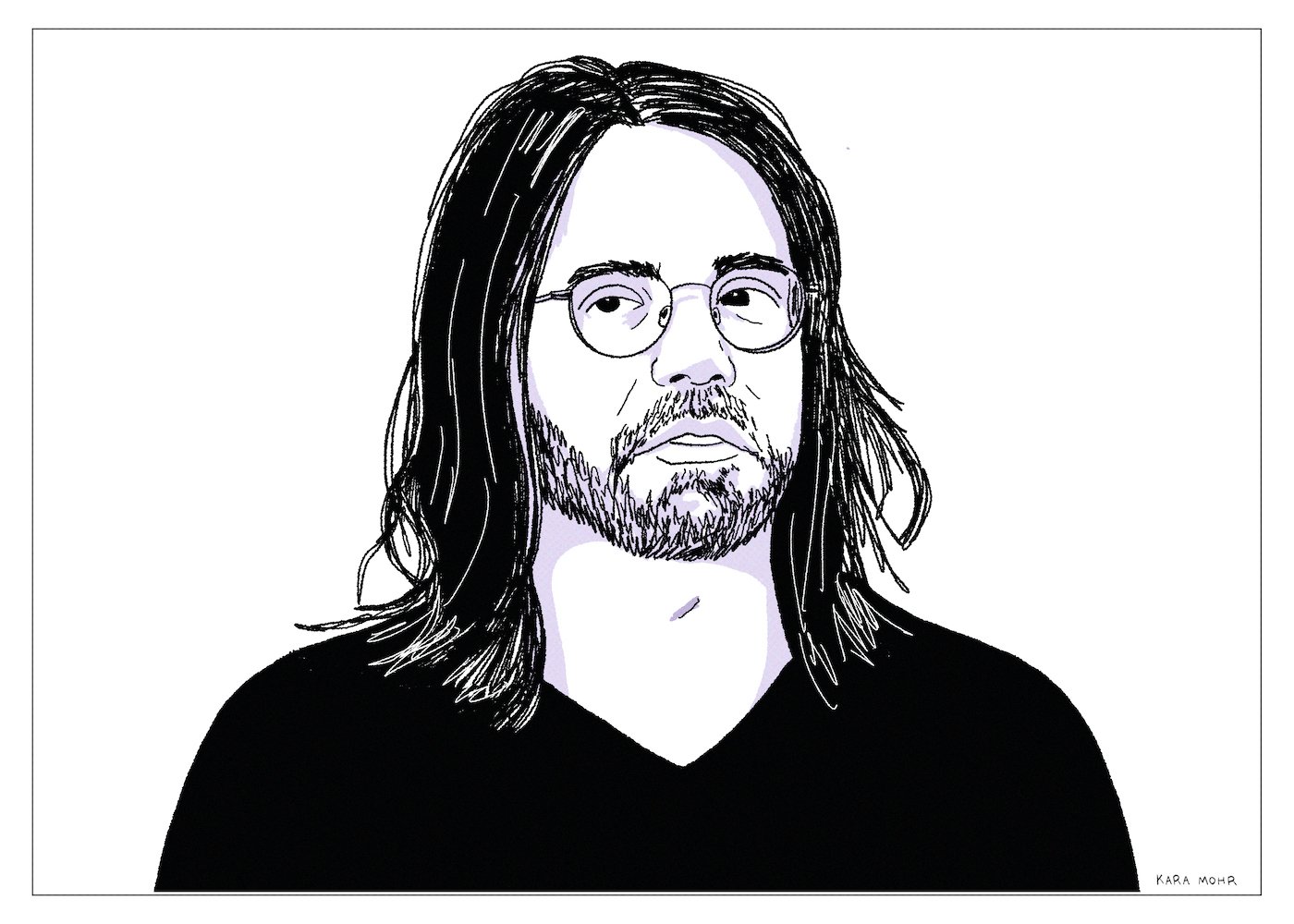

Tom Verlaine (1949-2023)

Of all of the many wonderful things said about Tom Verlaine this past week, the most moving words came, unsurprisingly, from Patti Smith. Her eulogy for The New Yorker, entitled “He Was Tom Verlaine,” was typically elegiac, like a series of black and white photographs narrated with poetic beats and prosaic secrets. Amid the generous obituaries and Twitter tributes — written mostly by strangers — Patti’s essay was so unusually revealing, not because she was betraying any confidences, but rather, because prior to this week, and despite the fact that I spent decades enamored of him, I knew so little about Tom Verlaine. He was not a recluse like Jeff Mangum or an outsider like Syd Barrett or Roky Erickson. But it seemed that, ever since “Marquee Moon” changed everything — and nothing at all — Verlaine was slowly, silently walking in the opposite direction from everything that fans (like me) most wanted from him. His entire career — seemingly confirmed by Patti Smith herself — is a reminder that love is so much more about what we don’t know than what we know for sure.

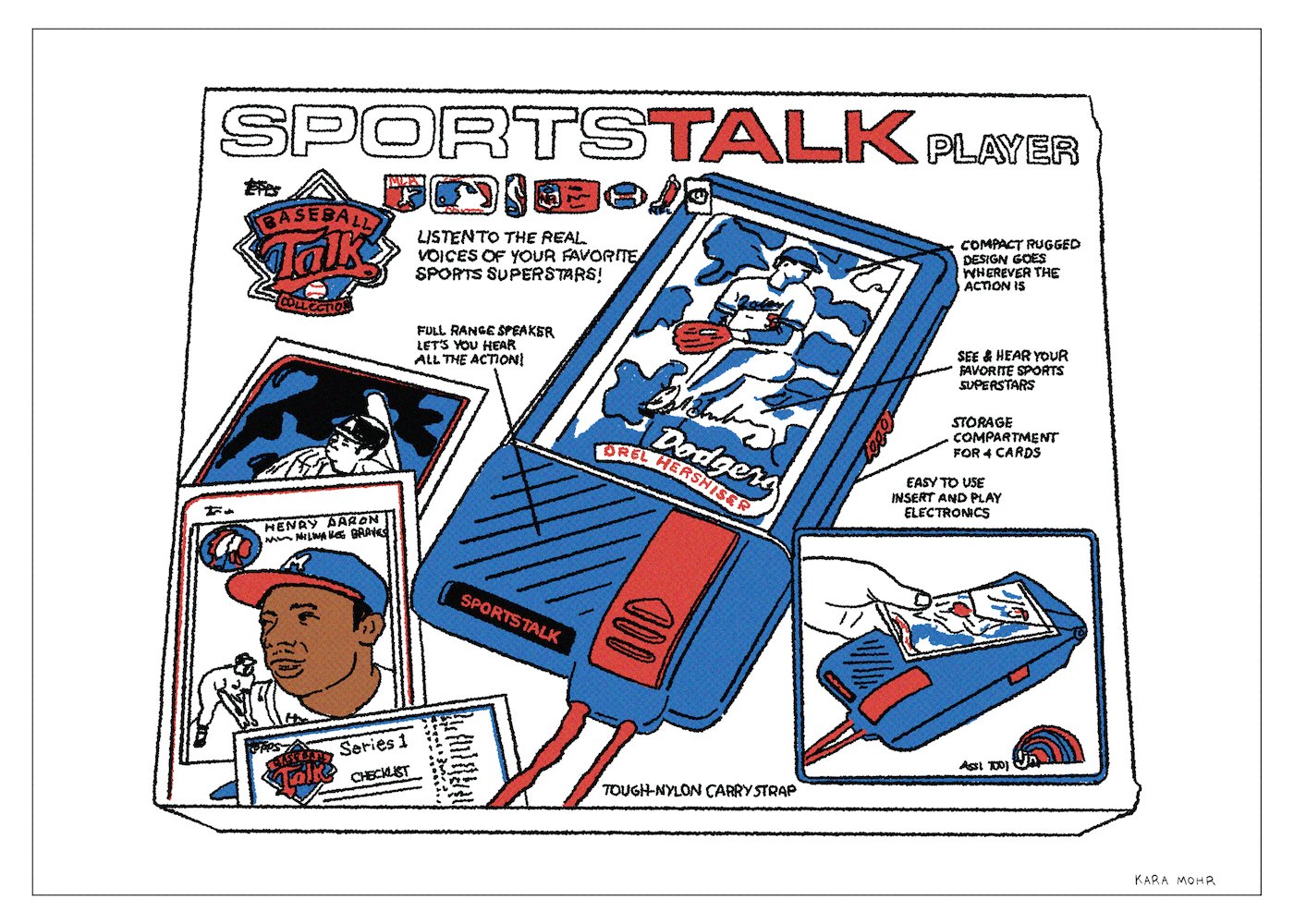

LJN Corporation “Topps Sports Talk Player”

First released in 1959, the Braun TP1 is a masterpiece. The phono-radio is considered by many to be a high water mark of twentieth century product design — its functionalism a complete validation of Dieter Rams’ “as little design as possible” ethos. Thirty years later the LJN toy company and Topps paid homage to Rams’ pièce de résistance with their Sports Talk player and Baseball Talk cards. The electronic player was actually a blue and red plastic portable phonograph and the cards resembled Topps’ bubblegum variety, except larger and with a miniature vinyl record pressed onto their backs. Like Rams’ TP1, the needle on the Sports Talk player sat beneath the records (cards). Like the TP1, the Sports Talk player was a feat of minimalist design and engineering. But unlike the TP1, the Sports Talk player was a piece of crap. Cheaply made. Easily damaged. Hard to explain and harder to understand. It lasted exactly one season and left behind a cautionary tale that fits somewhere between New Coke and “Ishtar.” For the record, though, I kind of dug New Coke. I thought “Ishtar” was pretty funny. And I freakin’ love my Sports Talk player.

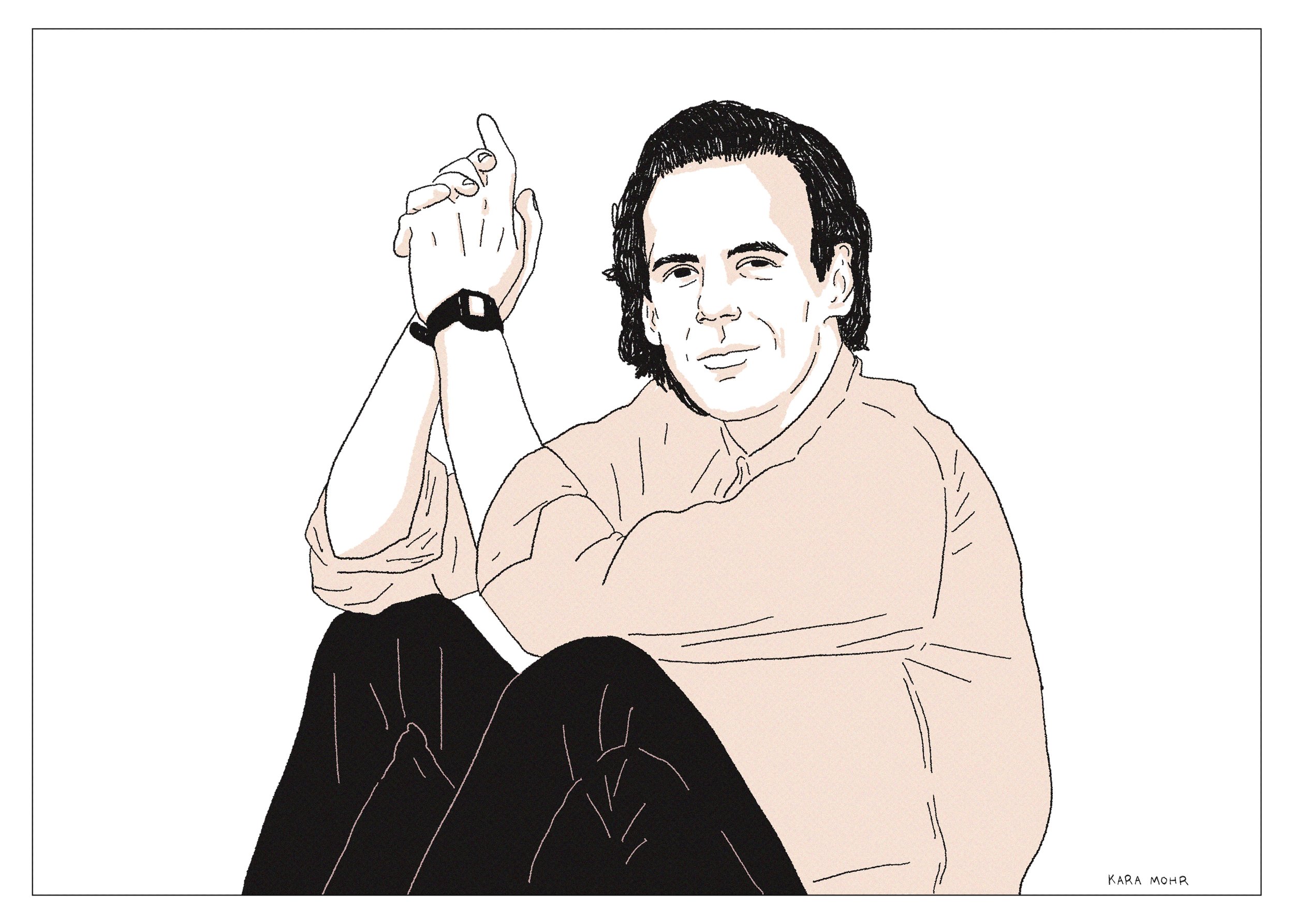

John Hiatt “Perfectly Good Guitar”

There’s a concept in child rearing — and I’m honestly not sure if it’s armchair psychology or actual science or what — called “perfectly adequate” parenting. Its premise is radically simple: that parents should be no more or no less than their child needs. One the one hand, it makes a lot of sense. On the other hand, nobody really wants to be “perfectly adequate.” Not in parenting. Not in life. Not in work. And, certainly, not in music. Pop music is defined by highs and lows. By mania and soul. The road in between is longer, and oftentimes much harder. It’s a workmanlike path — one that is rarely disruptive or revelatory, but is eventually, and amazingly, just right. Richard Thompson is always perfectly adequate. Sometimes more. Never any less. John Prine. Lyle Lovett. Nick Lowe. Always perfectly adequate. But of all the singers I can think of, the one who is most truly perfectly adequate — whose skill is evident, whose records are solid and whose faith and commitment is unwavering — is John Hiatt.

Dave Parker “The Masked Cobra”

Jim Rice stood six feet, two inches tall and weighed two hundred pounds. At the plate in Fenway, he looked like the perfect slugger. But, next to Dave Parker, he looked like Rocky standing beside Drago. By the late Seventies, Pops Stargell was the same height as Rice, but with fifty pounds of excess gut. And yet, next to The Cobra, Stargell looked like Santa hanging out with The Incredible Hulk. Dave Parker was not the greatest player of his era, but for several seasons, he might have been the most important — and the most feared. On July 16 1978, two weeks after breaking his cheekbone in a home plate collision, The Cobra returned to the line-up wearing a very basic, but entirely frightening, half white, half black protective mask designed for hockey goalies. As he made his run towards a batting crown and the MVP award, Parker looked not unlike Jason Voorhees dressed as a giant killer bee.

Gordon Lightfoot “Shadows”

To the cynical or the uninitiated, “Shadows” can sound like a Will Ferrell spoof — like music for lovers who refer to each other as “lover.” Like music to be played while wearing cable knit sweaters, sitting by the fire and sipping Canadian Club. But for those who either know Lightfoot’s oeuvre or who are familiar with Seventies Adult Contemporary Rock music, the sound is not unfamiliar. On top of twelve string acoustic guitar, delicate windchimes and lite violins, Gord’s boozy baritone narrates a slideshow about middle-aged resignation and that trip to the Bermuda Triangle. Released the same year as The Clash’s “Combat Rock,” Duran Duran’s “Rio” and Culture Club’s “Kissing to Be Clever,” “Shadows” was miles from anything hip or New Wave. It was the sound of a guy singing to himself, because he had to, because he was tired and lost and the world had moved on. It was the end of the line for Gord’s minor Pop stardom, the beginning of his sober second half and the most interesting album he made after “Sundown.”

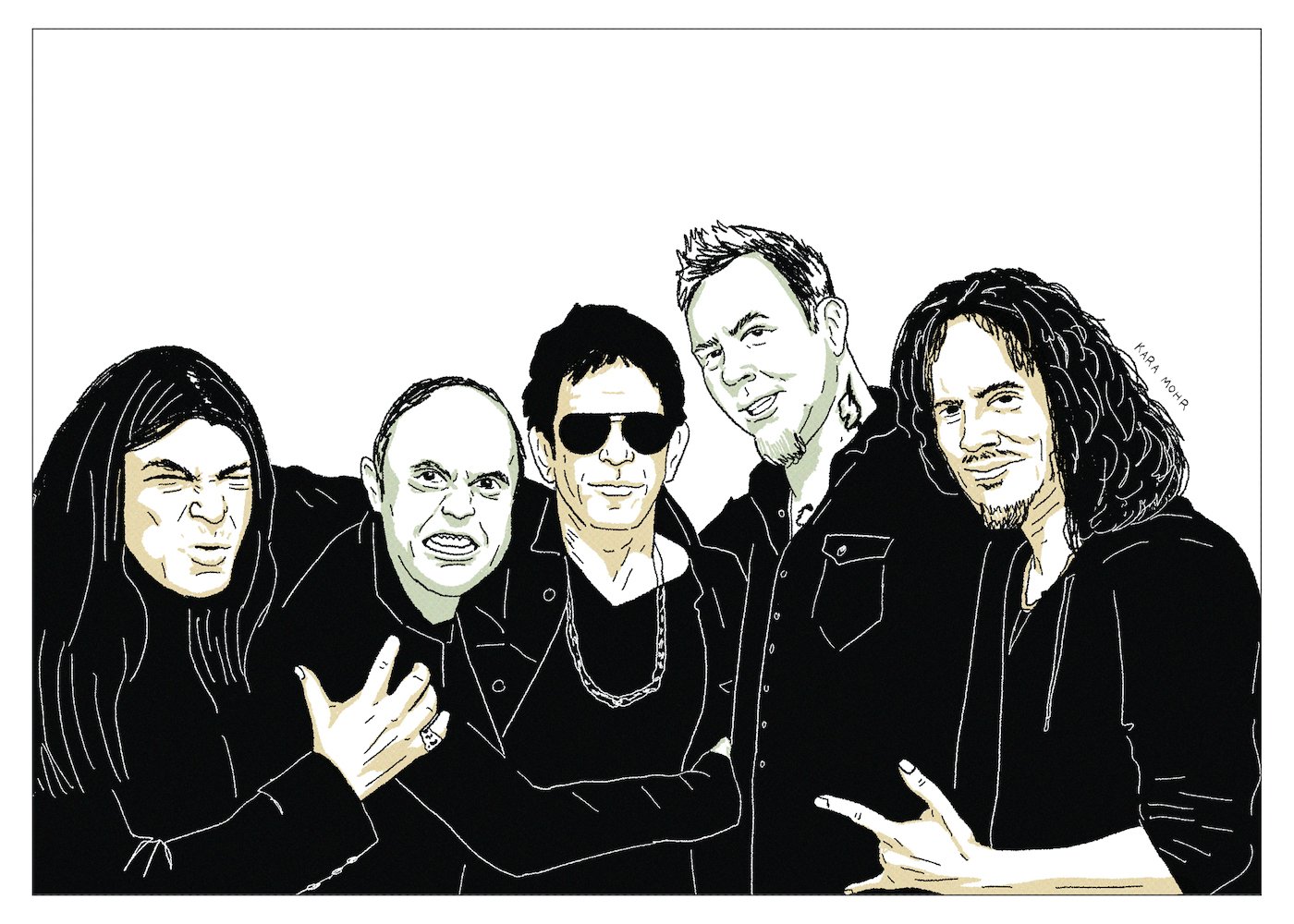

Lou Reed and Metallica “Lulu”

Given how few people have actually heard the album, and how few of those people are interested in anything beyond the stars involved, the volume of “Lulu studies” is staggering. But the divergence of the various theses is so bold as to suggest that either (a) people are listening to different albums or (b) nobody knows anything. There is, of course, overlap in the various perspectives — but less than I would have assumed. Many simply believe that “Lulu” is a historic failure — a bloated pretentious hour and a half of noise and nonsense. There are others who view it as an act of artistic bravery from two legendary artists, committed to a vision and unconcerned with failure. And, finally, there are those who believe that “Lulu” is misunderstood. Nowhere among the three points of view, however, can you find a faction who boldly proclaims: “Lulu is awesome.”

Tin Machine “Tin Machine II”

By the late Eighties, there were no fresh blood for David Bowie — the greatest vampire in Rock and Roll — to suck. The top Rock radio songs of 1988 included Henry Lee Summer’s “I Wish I Had a Girl” (what? who?), Bruce Hornsby and the Range’s “Valley Road” (rocks so light) and Tommy Conwell & The Young Rumblers’ “I’m Not Your Man” (not a typo, I checked). After two consecutive duds, Bowie was desperate for inspiration, but the pickings were slim. And so, he did what desperate people do. He found the nearest available guy and went all in. No research. No courtship. He just needed a guy with a beating heart, pumping blood and some capacity to make music. But mostly, he someone who could be a willing host to a brilliant parasite. Reeves Gabrels was that new host. And, in spite of his regal sounding name, he was truly just a guy — a guy from Staten Island, New York, who happened to be married to David Bowie’s tour publicist. One day, Gabrels was playing steel guitar in Rhode Island for a band called Rubber Rodeo. A year later, he was the cofounder of Tin Machine.

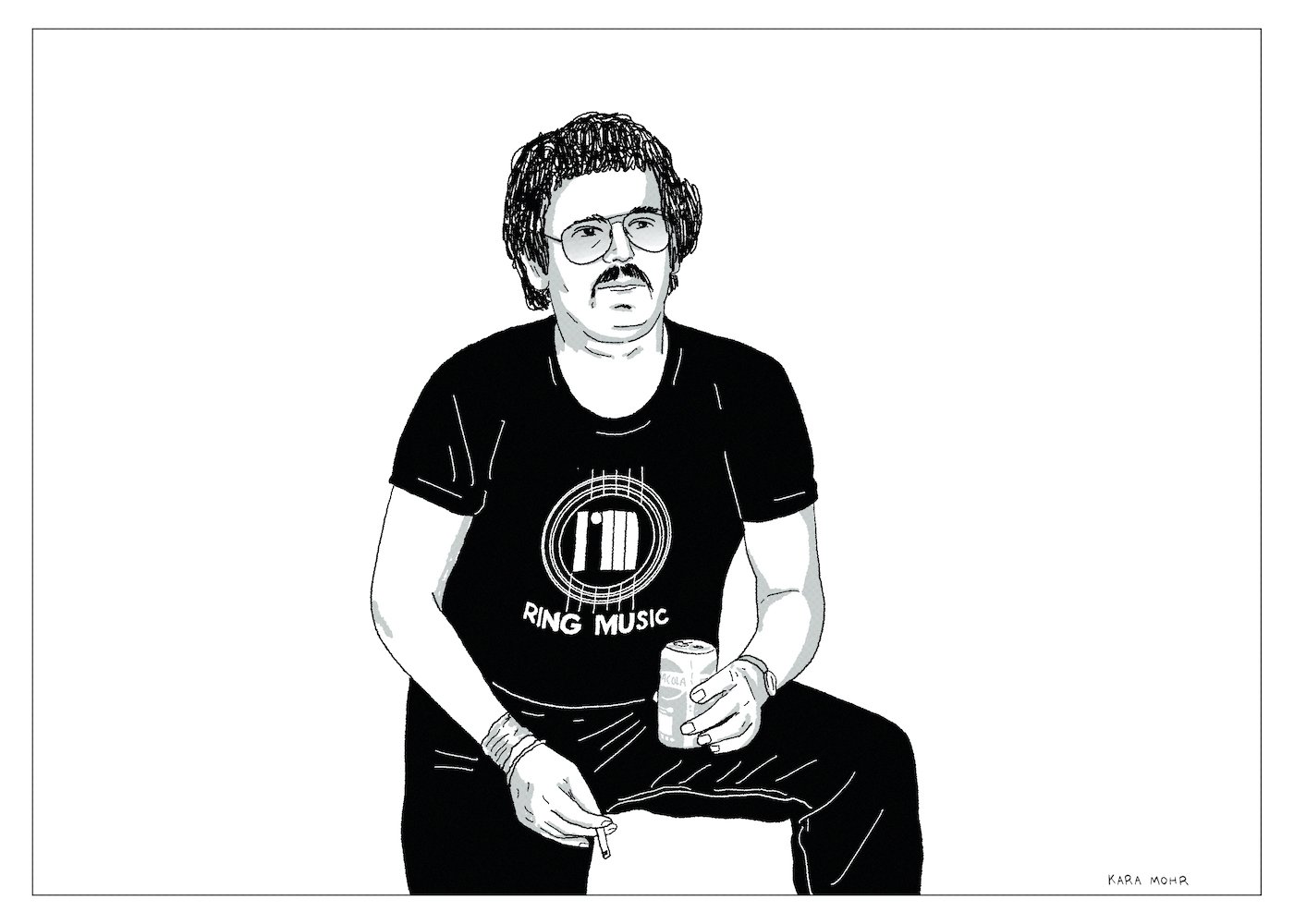

Warren Zevon “Sentimental Hygiene”

Following the unexpected success of “Excitable Boy” in 1978, Warren Zevon’s commercial prospects began to fade. “The Envoy,” from 1982, was predictably literate, frequently dark and occasionally brilliant. But, also, it flopped. Within a year of its release, Zevon was a black-out drunk divorcee, dropped from his record label and going nowhere fast. He licked his wounds, tried, failed, tried again, failed again and — eventually — succeeded in getting sober. It would be another five years before he released another album. In the interim, outside of his family, Jackson Browne, a bunch of L.A. session guys and a coterie of writers and critics, Zevon was more forgotten than he was missed. But then, in 1985, while Tom Cruise sashayed around the billiards table like a ninja pool hustler, Martin Scorsese dropped the needle on “Werewolves of London” and people suddenly started talking about Warren Zevon again.

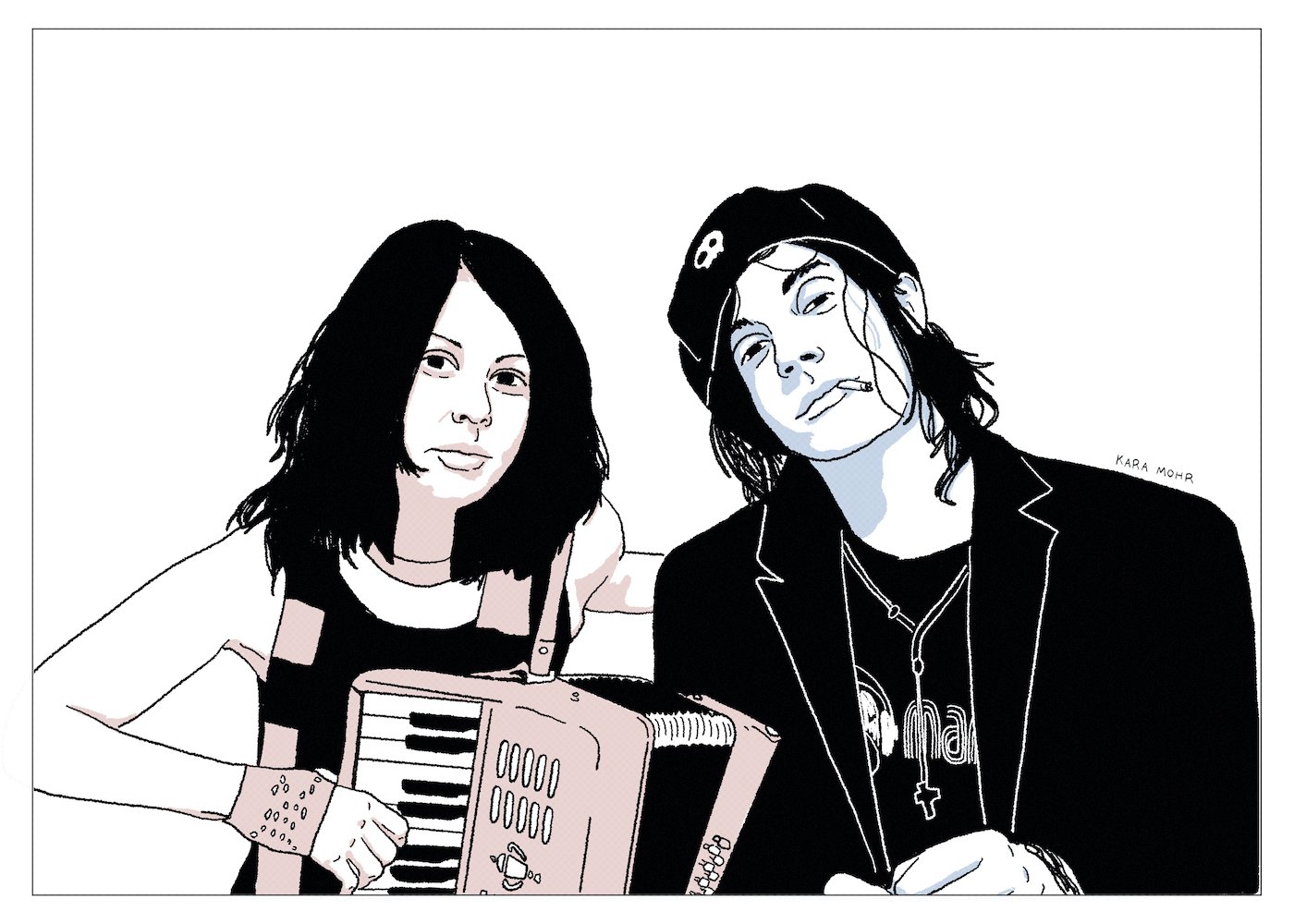

Marah “Marah Presents Mountain Minstrelsy of Pennsylvania”

The first wave of Dad Rock is canon — Dylan, The Band, Petty, The Boss. Occasionally, it veers into Indie or Alternative Rock (REM, The Replacements) or headier stuff (The Dead, Steely Dan). But, broadly speaking, it’s American Roots Rock for educated men who are older than thirty but younger than sixty, who are likely to drink craft beers and who desperately want their children to understand the glory of “Jungleland.” The second wave of Dad Rock is still a work in progress. In the early Aughts, bands like The Hold Steady and Band of Horses and Arcade Fire began to make their cases. Some of the neo-Dad Rockers were cut from The Boss’ cloth (Gaslight Anthem, The Constantines) and others were perhaps closer to Dylan (Bon Iver, Sufjan Stevens). But the ones who should have been kings — the ones who got it all started but then got lost in the plot — were Marah.

Fred Schneider “Just Fred”

Fred Schneider was an unlikely frontman. For one thing, he either could not or would not sing. Similarly, he seemed more interested in John Waters than in John Lydon. Fred never dreamed of making the next “Like a Rolling Stone.” He wanted to make the next “Monster Mash.” And so he spent over a decade, from “Rock Lobster” through “Love Shack,” blurring the lines between novelty Pop and artsy Rock. But, in 1996, at the very height of Alt, Fred Schneider reemerged as a solo act. During a time wherein “Alternative culture” had become overly serious, it was revealed that “Just Fred” was produced by Steve Albini and featured a cast of stalwart Indie Rock veterans as the backing band. On the surface, it sounded all wrong. No keyboards. No Kate Pierson or Cindy Wilson. No party. It seemed contrarian and willfully provocative, like hearing that sweet, adorable Alyssa Milano — Sam from “Who’s The Boss” — was making a turn into adult, erotic thrillers. But, in the same way that I definitely checked out “Poison Ivy 2,” I was not not curious about “Just Fred.”

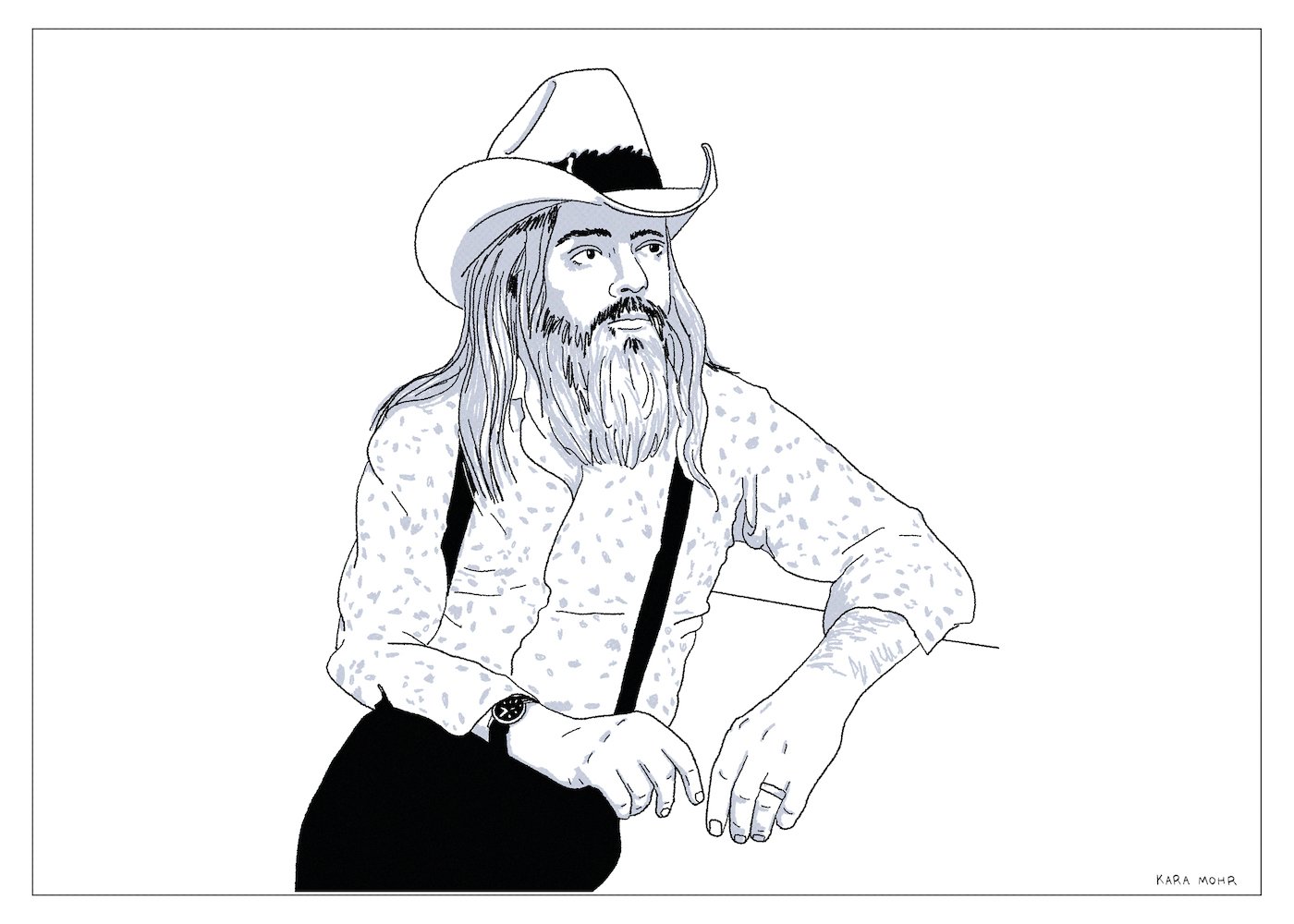

Leon Russell “Anything Can Happen”

Having spent more than a decade building his reputation as the “guy to call” when you needed a guy, Leon Russell was suddenly more than just “a guy.” He became “the guy.” In 1970, after touring with Delaney and Bonnie and releasing a critically adored solo debut, he put on his top hat, dusted off his beard and assembled the greatest live band on the planet for Joe Cocker’s “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” tour. And though the experience nearly killed him (and his bandmates), it marked the beginning of the next phase of his storied career. Whereas during the 1960s, Russell was on the side or behind the scenes, in the 1970s, he was a frontman, gracing album covers, standing center stage, and sharing the limelight with everyone from George Harrison to Willie Nelson. For a natural introvert who was perhaps meant to be a bandleader more than a Pop star, it proved to be too much for him. Depleted and lost, the man who’d released over a dozen albums in the Seventies, eked out only two the following decade. By the Nineties, he was stuck somewhere between the “where are you now” and the “who’s that guy” files. Leon Russell lost his way and then began to fade out, until, one day, Bruce Hornsby came a calling.

Keith Rainere “Totally Innocent Prog Rock Genius”

According to Nancy Salzman, at some point just before scoring the world’s highest IQ and becoming one of the world’s three greatest problem solvers, Keith Rainere taught himself many musical instruments, including the piano, which he could allegedly play at a concert level. Of the many claims made by NXIVM, I found this one most confounding simply because it is the most disprovable. During the nine hours of “The Vow’s” first season, the only proof we get of Rainere’s musical gift is a brief, middling performance of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” — a piece generally taken on by younger students in the first few years of their studies. On the basis of this showing, it’s hard not to conclude the obvious: Keith Rainere is no Keith Emerson. So, why? Why did he make such a bold and obviously false claim? IQ tests can be forged. Problem solving is hard to measure. But musical aptitude is hard to fake. The answer to my question arrived in the late Spring of 2019. According to the New York Post, some time after mastering all of those instruments but presumably before breaking the IQ test, Keith Rainere got really into Prog Rock — specifically Yes and Genesis. Which explains everything.

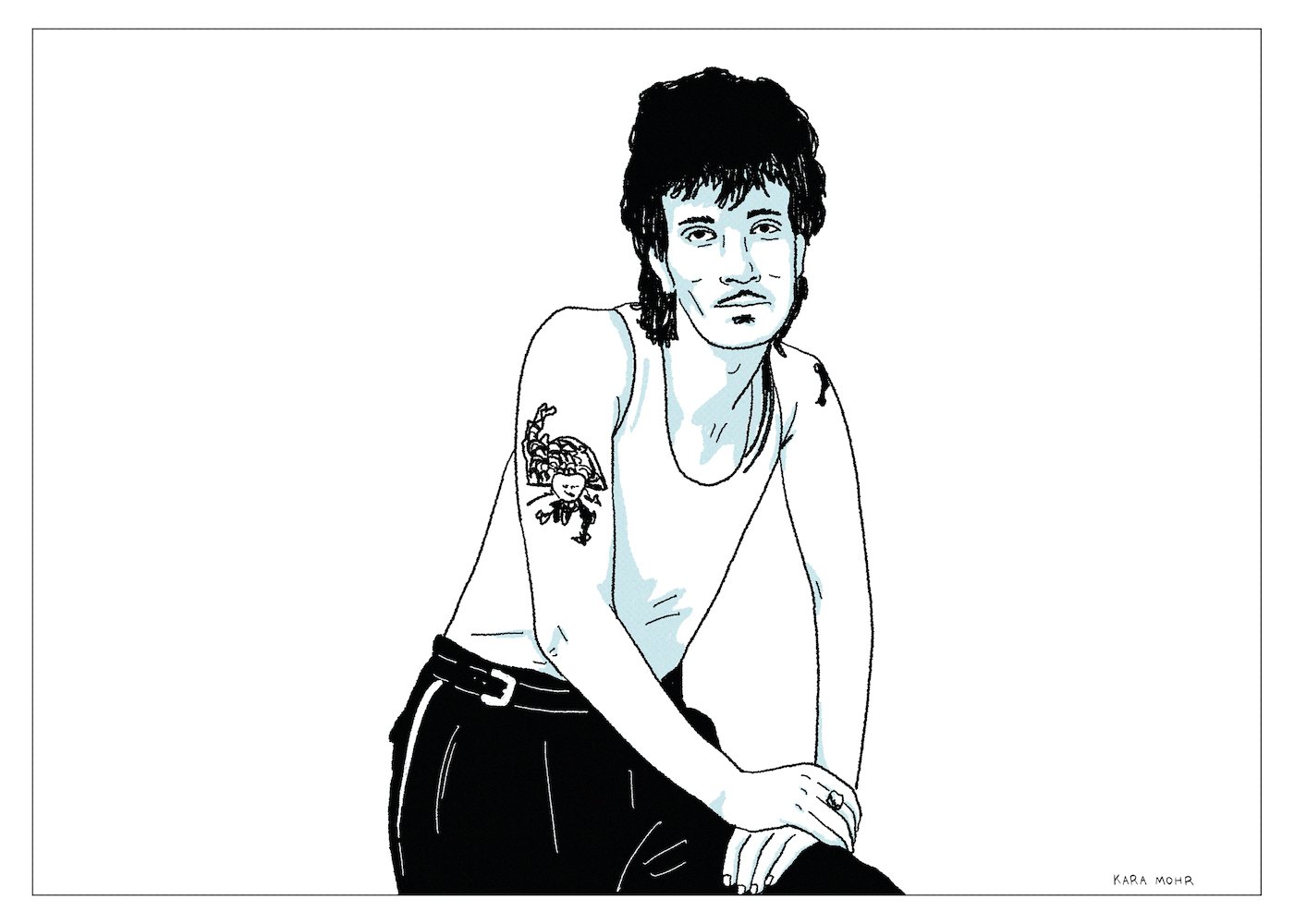

Willy DeVille “Backstreets of Desire”

When Dylan went from folkie hobo to poet in black turtleneck and shades, it seemed like affect. When Bowie went from Ziggy to Thin White Duke, it felt like an art project. And when Madonna went from Material Girl to S&M Barbarella, it came off like a marketing stunt. But Willy DeVille was the genuine article — a real life shapeshifter. The man born William Borsay Jr., from Stamford, Connecticut, would become a Spanish Harlem pimp, a Bowery gutter prince, a riverboat gambler, and a Navajo mystic. In 1992, somewhere between the Bayou and his eventual return to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, he briefly wound up in Los Angeles. And, in spite of crippling addiction and decades of commercial disappointments, Willy made one of the great, barely heard Roots Rock albums of the decade. “Backstreets of Desire” might read like something from Springsteen’s swamps of Jersey, but it sounds like the Los Angeles that made Los Lobos, Tom Waits and Warren Zevon.

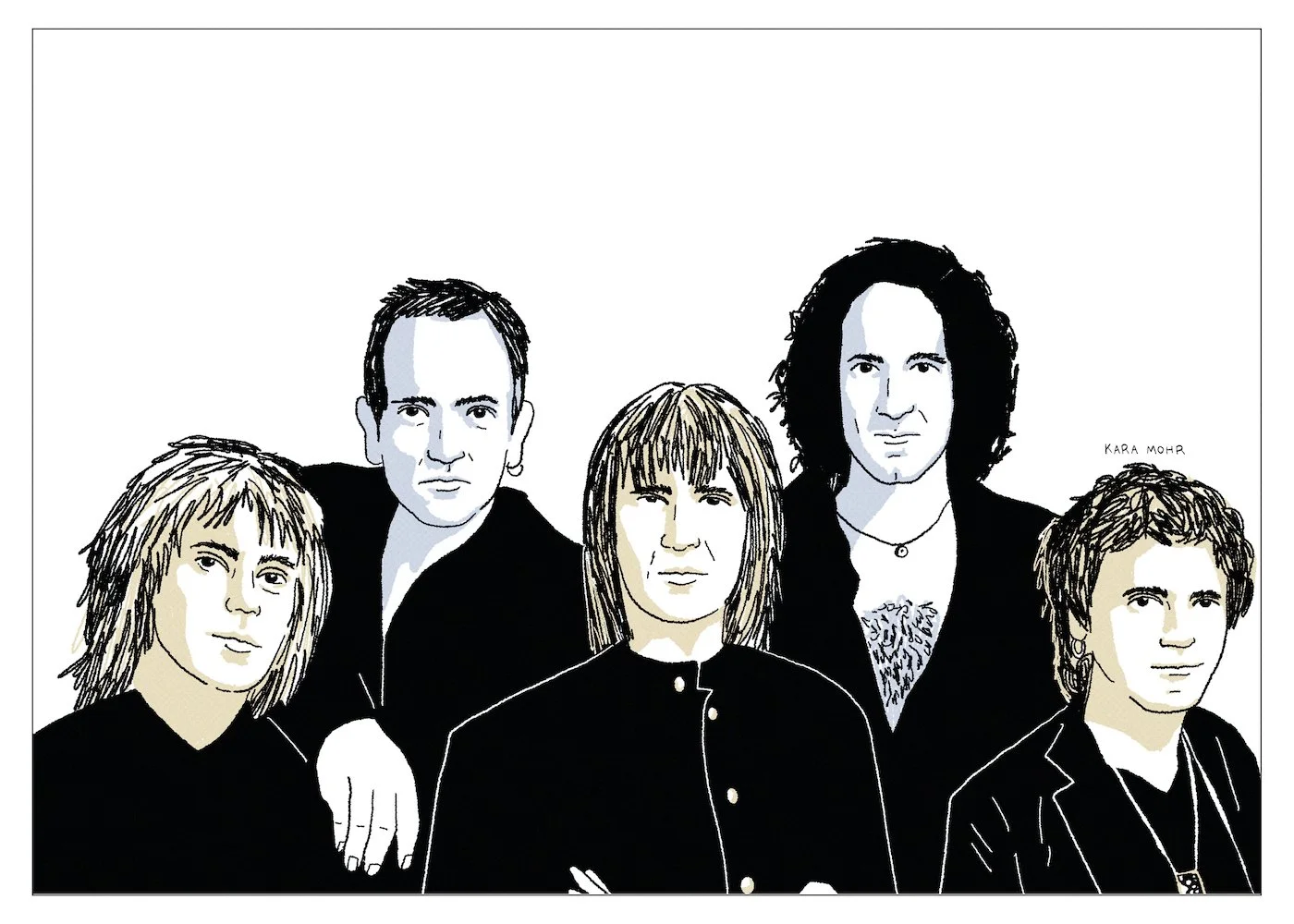

Bon Jovi “This House Is Not for Sale”

Though they were no longer America’s Biggest Rock Band, Bon Jovi could still sell (many) millions of albums. But it was clear to anyone who was paying attention that things had changed. Jon cut his hair and took up acting. Richie married Heather Locklear. Over the course of three decades, they’d traded in grit for nostalgia. Their fearlessness was subsumed by trite optimism. And though they’d sustained their spot on the charts, they’d regressed from something iconic to something more generic. By 2015, they had to confront the existential risk that all Arena Rock bands some day face: the challenge of being both universal and distinct. Many great bands had fallen into that chasm before: Journey, Foreigner and REO Speedwagon to name a few. But, not Bon Jovi. In just a few years, and without Richie Sambora, they went beyond arenas. Beyond namelessness and facelessness. They became the Bud Light of Rock and Roll — the highly consumable, mostly bland complement to Fox Sunday football.

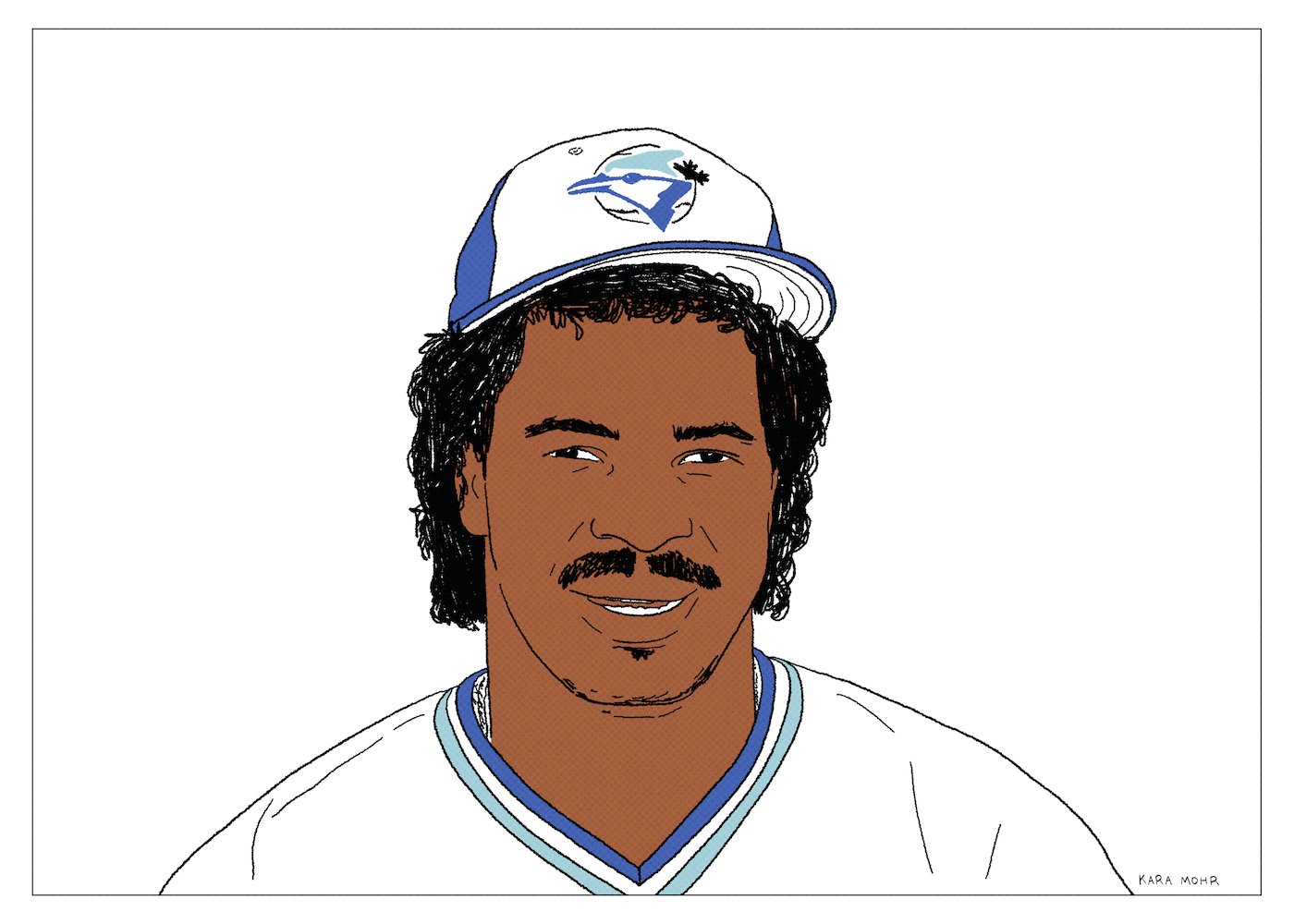

George Bell “Gone”

Having just been hit by a high, inside fastball, George Bell rushed towards journeyman pitcher, Bruce Kison, launched (and landed) a flying side kick and then immediately turned and connected with a two-handed flurry to the face of catcher Rich Gedman. Two years later, Bell won the AL MVP, edging out Alan Trammell in one of the closest races in award history. Advanced statistics, which were rarely employed at the time, have since suggested that Trammell was the far more valuable player that year. But, to my teenage eyes, George Bell was the guy. He hit towering home runs and batted over .300 and could turn into Spiderman if provoked. Back then, the Blue Jays’ slugger wore his cap on the tippy-top of his hair so as to not disturb his well-tended, lightly greased, semi-afro. That affect, with the hat perched up so high, reminded me of Apollo Creed ahead of his fight with Ivan Drago in “Rocky IV.” Like Creed, Bell’s hat “floated upon” more than it “fit on” his head. Like Creed, Bell’s external confidence betrayed some deep, inner terror. And, like Creed, George Bell completely disappeared from the sport that he’d once dominated.

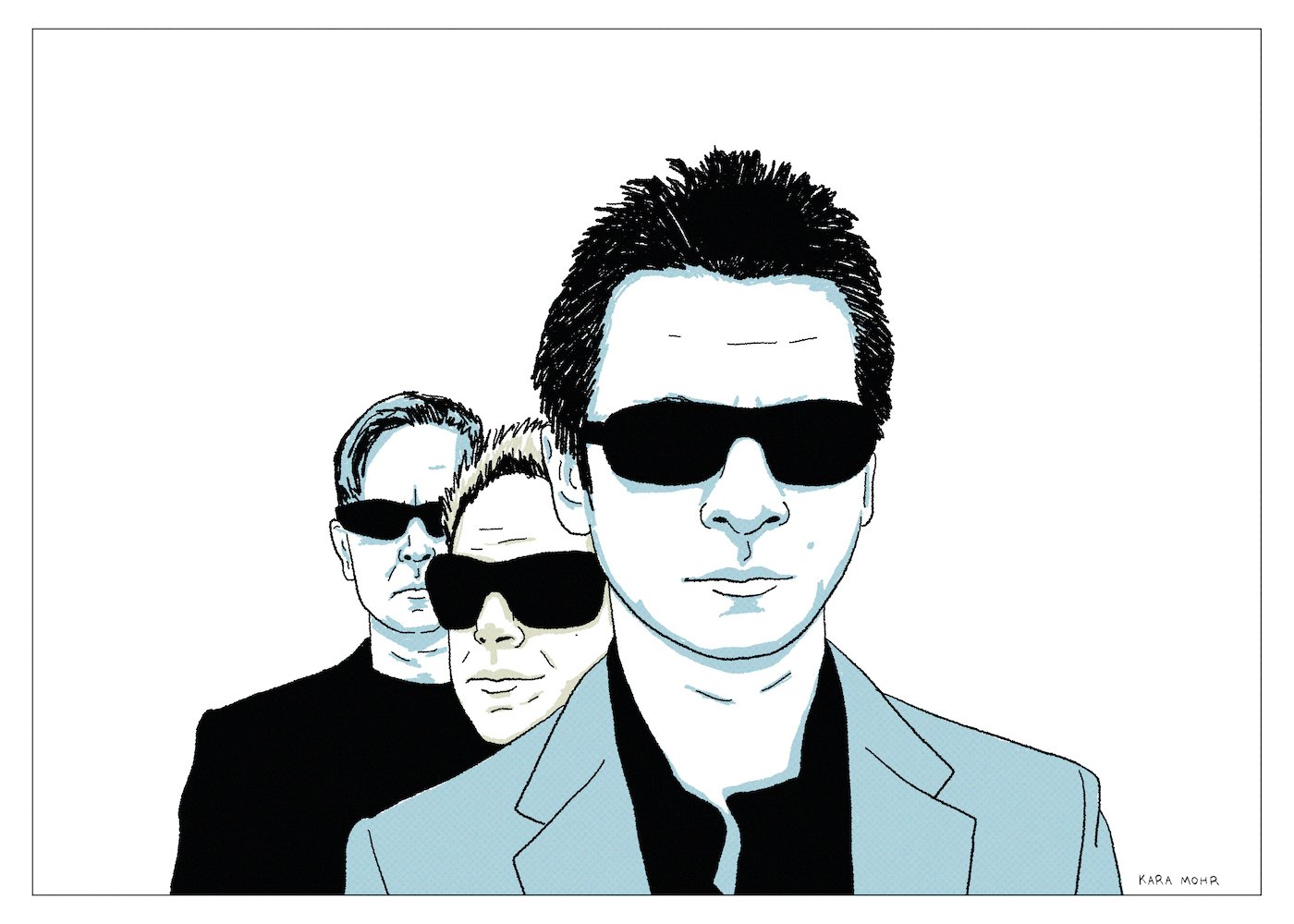

Depeche Mode “Playing the Angel”

By 1990, having graduated from new wave romantics to industrial futurists to “goth cowboy junkies,” Depeche Mode had inexplicably managed to conquer the world. And though they were churning — even rotting — on the inside, “Violator,” from that year, was inarguably their commercial and creative peak. It was also very nearly the death of the band. During the 90s, Gahan sunk deeper into heroin addiction, Gore was literally seized by alcoholism and Fletcher suffered crippling anxiety. The downward spiral continued until 2005, when Gahan, newly sober, and Gore, not sober and soon to be divorced, retreated with Fletcher to Gore’s home studio in Santa Barbara. The resulting album, “Playing the Angel,” was a deceleration and introversion following decades of the opposite. And while it was mostly a beloved album, it was not “peak Depeche Mode.” It’s a downing of the ante. It was also a minor miracle, recorded at the moment when the un-killable band suddenly seemed all too mortal.

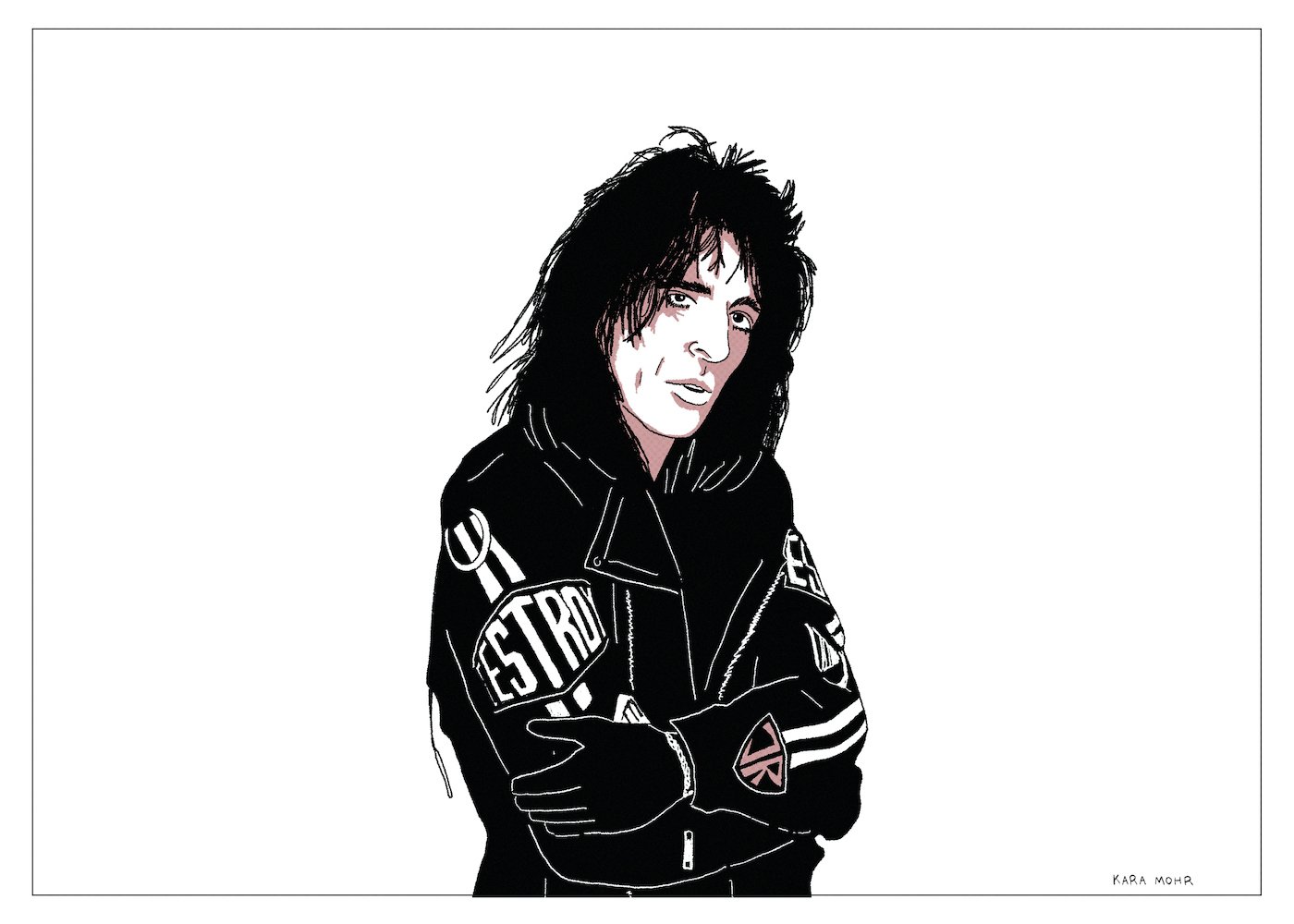

Alice Cooper “Trash”

The early 80s were not kind to Alice Cooper. Sober, but restless, he tried new gimmicks. He brought more snakes onstage. He tried his hand at New Wave. He traded booze for golf. But nothing seemed to work. By the mid-80s, while Hair Metal — a genre that he’d in part given birth to — was ascending, Alice Cooper was nothing more than a charming “has been.” But then, when it seemed that he was all past and no future, he caught a massive break. Desmond Child, a longtime fan and, more importantly, the super-producer of gargantuan, shout-along hits by KISS, Bon Jovi and Aerosmith, offered to help the forty year old, Shlock Rocker reclaim his throne. In order to succeed in the mission, Child had one requirements. He demanded that Cooper sing about the one thing that all teenagers are obsessed with but which the future GEICO spokesman had somehow avoided for his entire career: Sex.

Def Leppard “X”

Def Leppard were once as American as apple pie. More than Bruce or Petty or Johnny Cougar, they were the soundtrack of the American Heartland. They were the grist for Rock radio, churning out pristine, semi-heavy, fully melodic singles, engineered by the future Mr. Shania Twain. With the arrival of Grunge and Alt, however, came the annihilation of Hair Metal. And though they did not precisely fit the genre, Def Leppard was a casualty of the 90s. On the brink of extinction, they tried everything to survive. They tried sounding like Stone Temple Pilots. They tried sounding like themselves. And then, finally, desperately, they tried the unthinkable. They hired wunderkinds Marti Frederiksen and Max Martin and made a bunch of tracks that resembled the third best songs from “American Idol,” if recorded by Bryan Adams for the Nordic market. On “X,” Def Leppard tried mightily to reclaim lost ground, but ultimately fell short of “popular” and landed awkwardly in the neighborhood of “pop.”

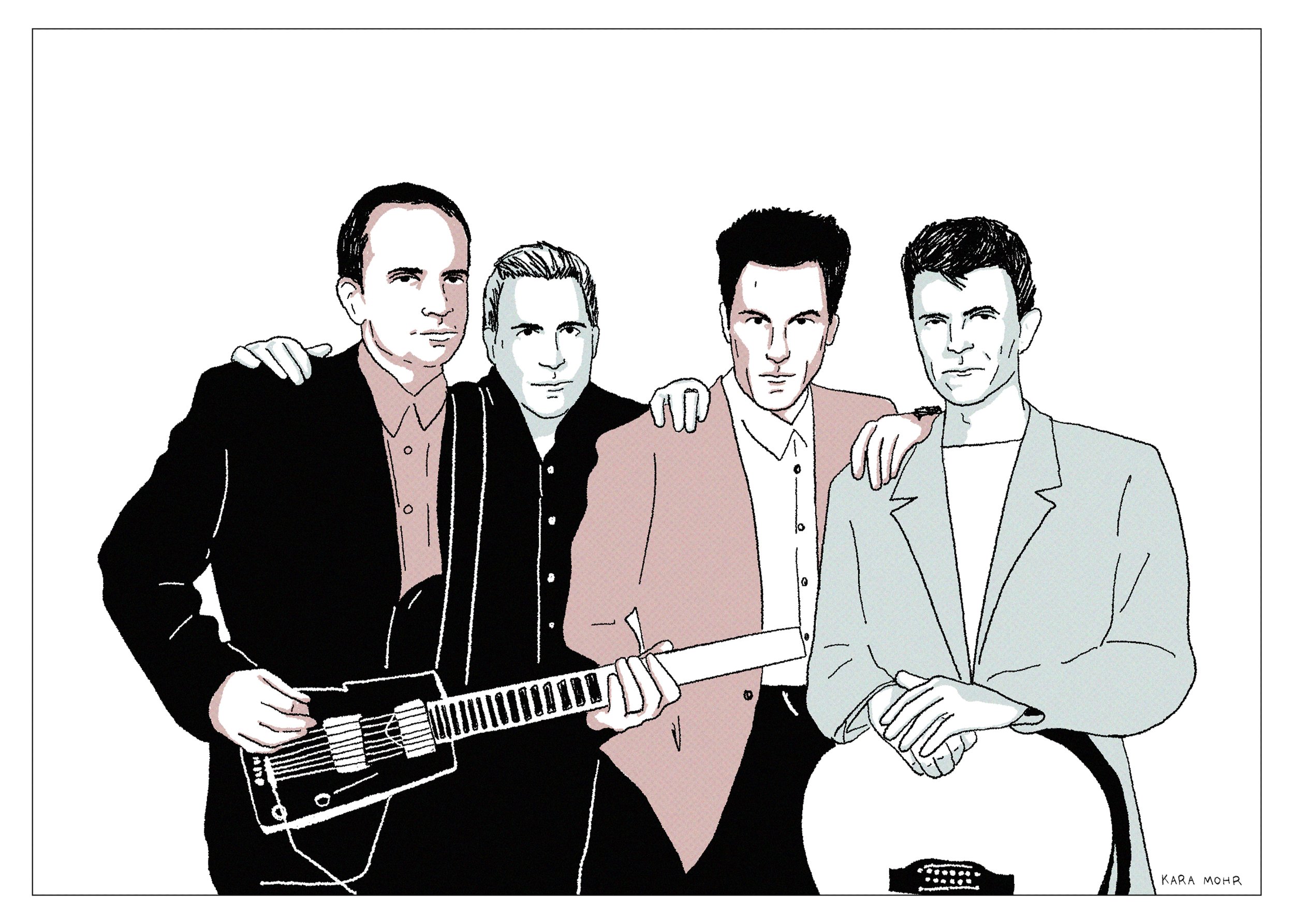

Art Garfunkel “Scissors Cut”

From 1970 through 1973, Art Garfunkel was among the most fascinating men in America. Coming off of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” he turned his attention to acting, where he made his debut in Mike Nichols’ “Catch-22.” The next year, he was nominated for a Golden Globe for “Carnal Knowledge.” Eventually, though, he reemerged as a solo recording artist. “Angel Clare,” from 1973, produced two top forty singles, and a series of Gold and Platinum-selling albums soon followed. What began as warm possibilities, however, devolved into flaccid melodies and artistic stagnation by the end of the decade. And then, tragically, Garfunkel’s romantic partner of many years, Laurie Bird, committed suicide in 1979. Most of America was depressed in 1979, but Art Garfunkel was more depressed. 1981’s “Scissors Cut” is the evidence of that depression — a bawling, private eulogy, pressed onto vinyl. It was also the end of “Art Garfunkel, Pop Star.”